Alt-Right

The Globalisation of Ethnonationalism

Art and ideas that had been dreamed up on one side of the world could reach and change people on the other.

In Reading Lolita in Tehran, the Iranian author and professor Azar Nafisi discussed her experiences teaching the novels of Austen, Joyce and Nabokov to Iranian students as the Islamic Revolution transformed the country. Nafisi related their themes of empowerment and resistance to the oppression and the censorship she saw around herself. For liberals, this was among the most inspiring stories of globalisation. Art and ideas that had been dreamed up on one side of the world could reach and change people on the other. Liberal values could take root in authoritarian societies and grow, and spread their branches and flower throughout them.

This has always been a challenge for conservative governments and nationalistic governments. “European civilisation will have a beneficial effect on us,” said the Turkish nationalist Ziya Gökalp:

… not only with its science and technology, but also in matters of taste and morality. But this influence is permissible only to the extent that it helps dismantle the Persian one. The moment it attempts to supplant what it destroys, it has itself become harmful and should be resisted.

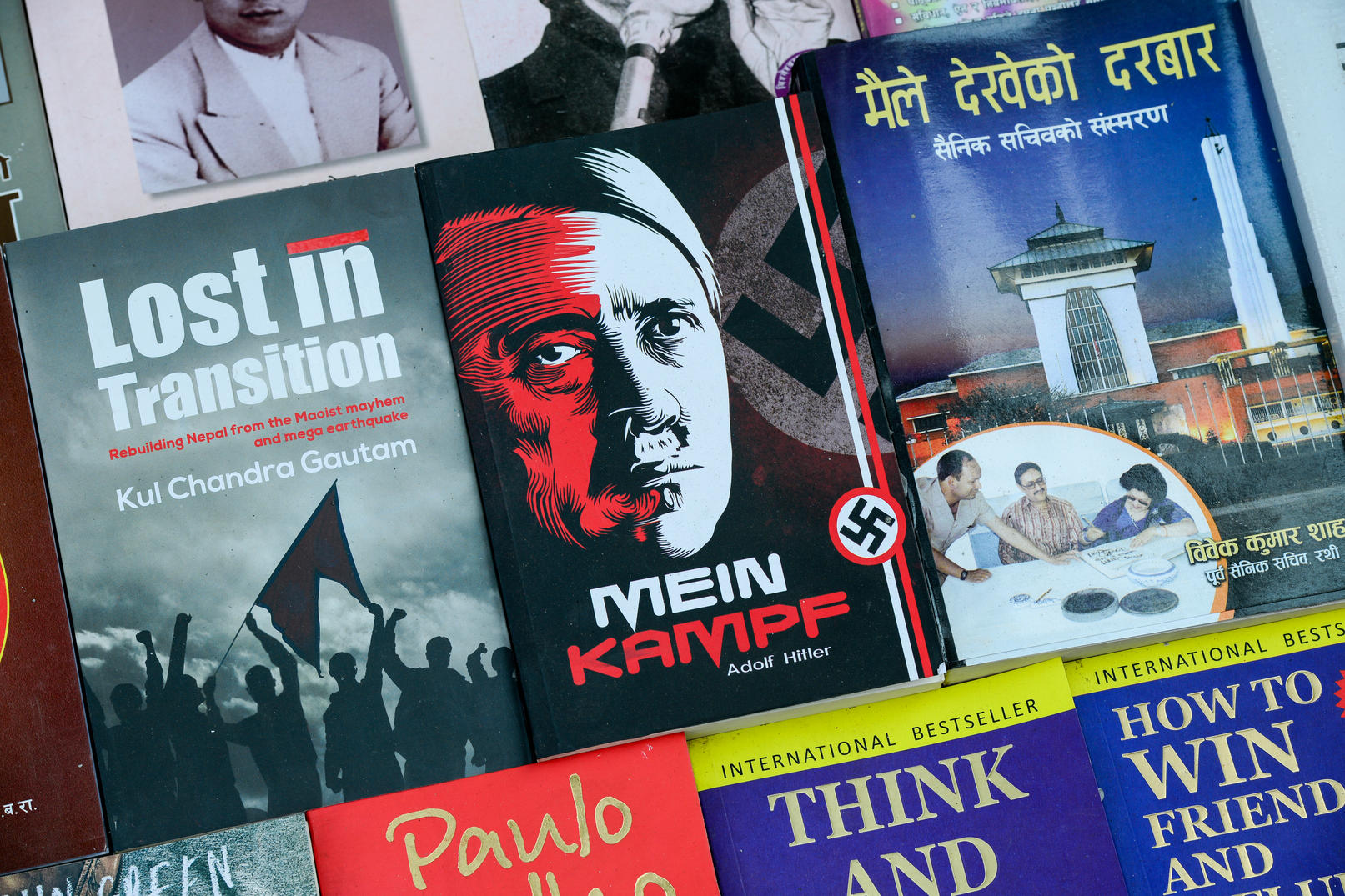

Yet, of course, illiberal values can be spread as well. Once, Karl Marx was an obscure German-Jewish philosopher scribbling away in London as his family starved to death at home, but in time his ideas reached everywhere from Cuba to Korea. Sayyid Qutb, an Egyptian Islamist ideologue, inspired jihadis around the globe.

So it is in the Twenty-First Century. The Christchurch killer’s manifesto, as I have written, is so full of in-jokes that it is difficult to tell what is sarcastic and what is serious. What is clear, however, is that the man had a vast array of international interests and influences. He called himself an “eco-fascist” (despite saying little about the environment). He lionised the British fascist Oswald Mosley. His favourite government was China’s. He wrote about conflicts in the Balkans, and Central and Eastern Europe. His title, The Great Replacement, was a reference to the work of the reclusive French anti-immigration author Renaud Camus, who commented, not especially convincingly:

I worry about our Muslim friends. I think that for security they should gather in a large fortress, the “land of Islam” (fifty seven countries anyway…), and live in peace according to their tastes and according to their faith, well protected against the imbalanced.

The Christchurch killer’s potpourri of influences reflects the curiously international nature of white nationalism. Rather than nations having their own united, cohesive political movements they tend to have fragmentary and contradictory groups, drawing on ideological trends from around the world.

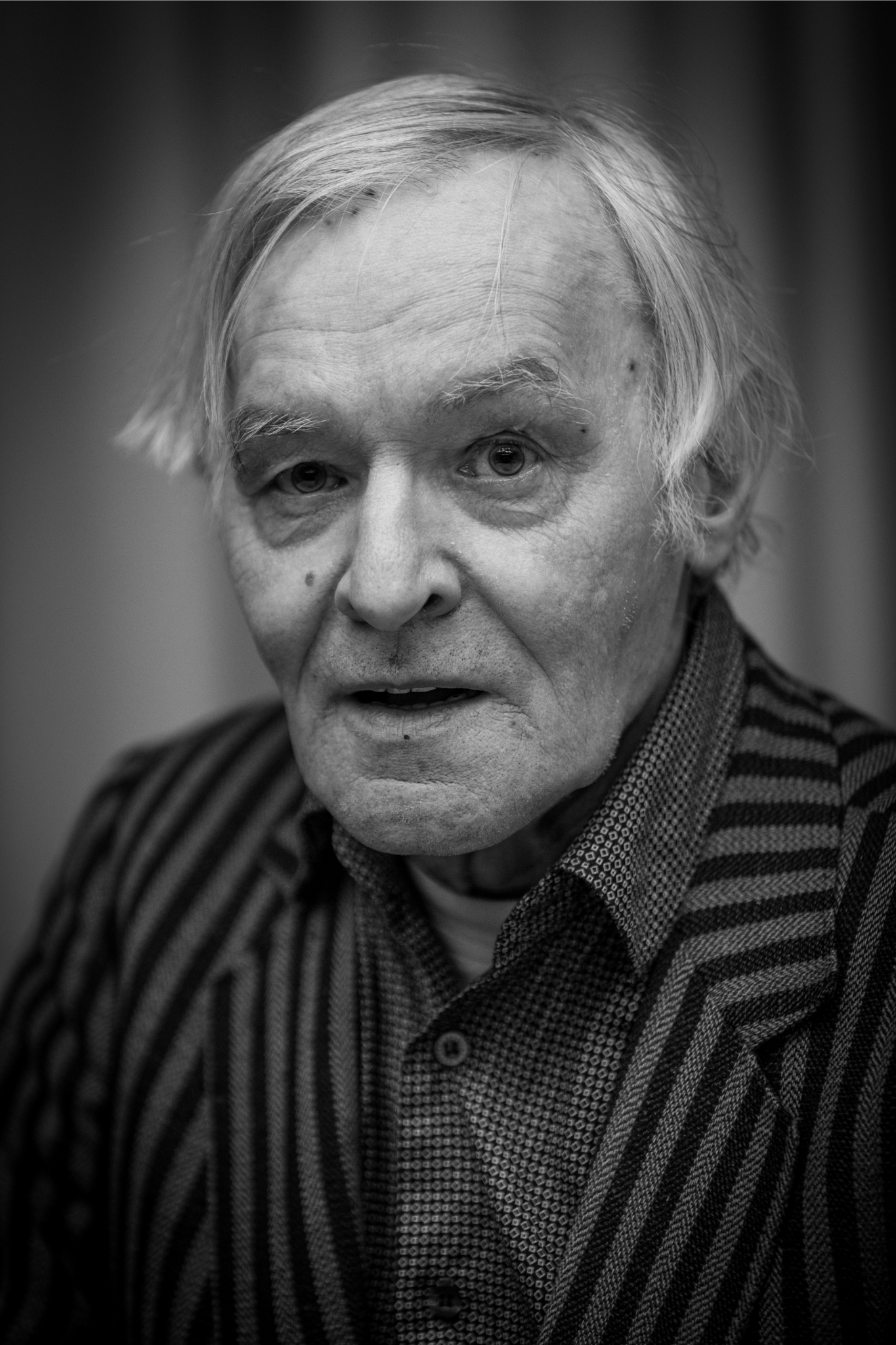

“Eco-fascists,” for example, among whom the Christchurch killer placed himself with arguable levels of seriousness, are influenced by an austere Finnish fisherman named Pentti Linkola. Linkola believes that if human beings are to coexist with nature, the only solutions mass death and severe birth control. “Who misses all those who died in the Second World War? Who misses the twenty million executed by Stalin? Who misses Hitler’s six million Jews?” Eco-fascists add, of course, that if any population should survive the mass death it is theirs. Linkola does not call himself an eco-fascist but he has endorsed at least some form of tribalism when he has written:

What to do, when a ship carrying a hundred passengers suddenly capsizes and only one lifeboat? When the lifeboat is full, those who hate life will try to load it with more people and sink the lot. Those who love and respect life will take the ship’s axe and sever the extra hands that cling to the sides of the boat.

Naturally, most white nationalists would not accept Linkola’s ideas. They like modern material standards. They want success for all white populations (most of whom Linkola, one suspects, would see as hands grasping at the sides of his boat). They would not endorse the kind of cheerful misanthropy that has led Linkola to praise the terrorist attacks of 9/11 as a “splendid choice.” But some do, and the more incompatible elements one’s “movement” has the less it can even lay claim to the word.

More contentious than environmentalism has been faith. Fascism has always contained an odd mélange of religious and supernatural ideas. French nationalists like Charles Maurras tended to promote authoritarian forms of Catholicism while the Italian radical traditionalist Julius Evola was a bitter critic of the Catholic Church. Within the Nazi hierarchy, Christians and pagans uneasily coexisted.

The modern Alt-Right has taken this diversity to comic levels. The Alt-Right Corporation, a hubristic attempt to centralize the movement’s different strands, was founded by Richard Spencer, a Swede named Daniel Friberg and an Iranian-American named Jason Jorjani. Jorjani, a well-heeled academic, was best known for a book titled Prometheus and Atlantis, which argued against “Abrahamic religion” and in favour of the existence of paranormal powers and the wisdom of Hellenic and Oriental faiths. Jorjani left the Alt-Right in 2017, complaining that it had become “a magnet for white trash” who did not appreciate his esoteric intellectualism.

When Trump was elected, there was a real chance for radical nationalists to win supporters to their cause. Few things were more detrimental to the Alt-Right’s chances than the essential cosmopolitanism of their leadership. The white nationalist rank and file were baffled to fire up Alt Right.com at Easter, for example, and find an essay extolling the pagan origins of the festival. This, along with other internal and external factors, helped the Alt-Right to dissolve into a stream of political and religious microcultures.

An essential force in modern white nationalism has been the publishing house Arktos, which publishes authors from across the dissident right, insisting: “Arktos does not seek to propagate any specific ideology, system of beliefs or viewpoint, nor do we seek consistency.” There, curious readers can find conservative, fascist, pagan and even Hindu books from authors as diverse as Charles Maurras and the Indian spiritual guru Sri Sri Ravi Shankar.

One of the most notable authors published by Arktos was the French white nationalist Guillaume Faye. Some of the most profound influences on the Alt-Right have been French. It was from Alain de Benoist, who claims to oppose the movement, that the concept of “ethnopluralism”, or a focus on ethnic difference rather than ethnic supremacy, emerged. Faye, who died of cancer earlier this year, was more polemical and less elliptical than his countryman. In his book A Global Coup, he wrote:

The current geostrategic divide must not be allowed to conceal tomorrow’s ethnic reality, the reality of a world in which Whites will find themselves ever more threatened and in a minority position, and will thus be compelled to regroup.

Faye envisaged a union of white people’s that he called Septentrion:

Septentrion can be defined as the regrouping of all peoples of albo-European descent located in the northern hemisphere, spanning from North America to Europe and the Russian Federation, in addition to two crucial septentrional extensions: Argentina and Australia.

One might think that the Christchurch killer is a sign of the realisation of Faye’s ambitions. Here, after all, was an Australian who had been inspired by European conflicts with Muslim populations to enact terrorism that, he hoped, would fuel racial violence in the United States of America.

I suspect, however, that these crimes are not illustrative of the plausibility but the implausibility of Faye’s ideas. White nationalist circles are so thick with different international influences that they have no individual or collective coherence. This does not preclude there being terrible crimes from unhinged, brutal sociopaths but it makes any political organisation difficult.

One popular criticism of globalisation, on the left and the right, has been that it promotes atomisation as traditional religious and communal identities are broken down and replaced with a varied political, spiritual, cultural and consumerist phenomena. The communist Zygmunt Bauman and the traditionalist Alain de Benoist have had remarkably similar perspectives on what Bauman calls “liquid modernity” – a time where identities, beliefs and relationships are in flux. Ironically, white nationalism, which is so hostile to liberals and globalists, is symptomatic of these tendencies: a vague internationalist ideology which exposes people to such a variety of influences, rarely rooted in their own collective life, as to produce difference and alienate them from each other. Thus, a supposed weakness of liberalism becomes its own perverse form of strength.

Correction: The Christchurch shooter was originally misidentified as a New Zealander. Apologies for the error.