History

Understanding Modern African Horrors by Way of the Indian Ocean Slave Trade

The modernizing elites of these groups then fought with the British during WWI and WWII, and demanded independence after the war, which they got.

On January 15, and well into the morning of the next day, terrorists affiliated with the Somali Jihadi group Al Shabab forced their way into an upscale Nairobi hotel and business centre, killing 21 innocent civilians. Kenyan authorities, with some help from Western allies, killed some of the terrorists and captured the rest. Al Shabab justified the attack by denouncing the Kenyan government’s participation with African Union forces in Somalia, which has been in a state of civil warfare since the early 1990s.

I had driven by the targeted complex a couple of days before the attack, and once lived in this neighbourhood back when Kenya was my permanent home. On this visit to the country, I’ve noticed that—notwithstanding January’s terrible tragedy—tourism is booming, agriculture is bountiful and the Kenyan elite are benefiting from the massive Chinese investments that have transformed the landscape. The overall degree of improvement depends on which expert you believe. But the plethora of expensive cars that now jam the streets of Nairobi, and the building boom on display in many parts of the city, do suggest a surging economy.

Anyone who knows the history and tribal dynamics of East Africa and the Horn will understand that even if the Kenyan government pulled all its troops out of Somalia, Al Shabab likely would still try its best to destabilize this country. I outlined the reasons for this decades ago, when I first briefed visiting Canadian and U.S. military personnel here in Nairobi. Many of the things I told them remain as true now as they were then. That’s because the most important factors at play are rooted in history, not in recent geopolitical developments.

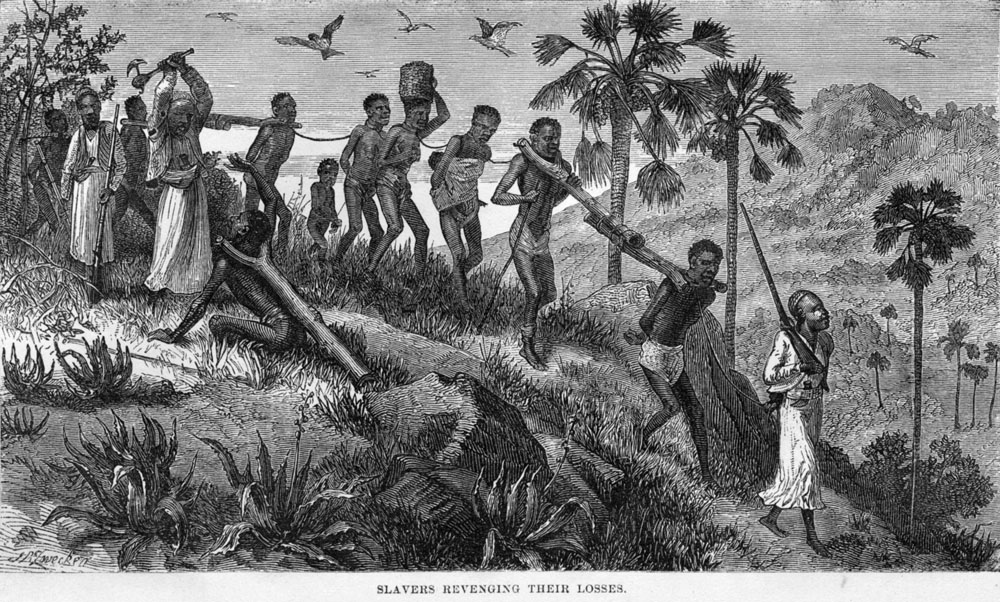

Specifically: Many modern problems in the area are rooted in the Indian Ocean slave trade—a scourge that was distinct from the better known slave trade that preyed on West Africa. In the eastern part of the continent, there was little to no European involvement. The practice was indigenous and ancient, and lasted more than a thousand years.

The rise of Islamic societies propelled young Arab and Persian men to the Indian Ocean coast, from Somalia down to Mozambique. There, they married local women, converted locals to Islam and established sophisticated coastal trading cities that featured advanced stone architecture, relatively high rates of literacy and even, in some cases, indoor plumbing. This is where they developed the lateen sail (though its origins remain disputed by historians), which allowed them to take advantage of alternating monsoon winds, so as to sail their trading dhows to India and back to East Africa every six months. These were the seas plied by the fictional Sinbad the Sailor. East Africa’s coastal elites brought gold, ivory, spices and slaves from the interior of Africa and sold them to customers in the Middle East and India.

During the 19th century, the Omani sultans relocated their sultanate to Zanzibar, in what is now coastal Tanzania. They used slaves to work their clove plantations, and presided over a large-scale traffic in human beings from the coast to the Congo. As the interior tribes were not Muslim, the Arabs, Swahili and Somali felt free to raid their “infidel” communities. The East African/Central African slave trade was a brutal overland version of the oceanic horrors known to historians of the Western version. Untold hundreds of thousands died before they reached the coast.

This was the Africa that was discovered and first described by missionary explorers such as David Livingstone, who documented the horrors of the East African slave trade on behalf of Victorian England. At that time, the empire recently had banned slavery, and was swept up in an evangelical abolitionist movement. This culminated in Britain occupying the East African coast of the Indian Ocean, taking out the power of the Zanzibaris and establishing their own newly created colonial authority as far as Uganda. From the African point of view, this was a case of European colonialists displacing Muslim slavers.

Together with the French and Italians, the British divided up Somaliland (after a lengthy campaign against a Jihadi leader named Mohamed Abdullah Hassan), whose Somali inhabitants had been willing partners in the East African slave trade (with the Swahili). In this way, the colonial boundaries of what later became the independent countries of Somalia, Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania were established. But of course, that did not stop tribes from moving this way and that across borders that looked real on the map but felt imaginary on the ground.

Although the Somali-speaking peoples of the Horn of Africa all generally follow the belief that they descend from a single man named Soomal, and practise Islam and Islamic saint worship, they continue to be divided into two major tribal confederations. The northerners, called the Isaak, recently have managed, alongside other clans, to establish a near-functioning democracy in the northern Somaliland (which was once a protectorate of the British Crown). To the south is the land of the Darod clans, where the civil war has been raging since the 1990s.

These Darod clans, which are still largely nomadic, gradually have been expanding southwestwards in search of new grazing lands to occupy with their herds of camels, cattle, sheep and goats. Until the late 1890s, they were barely present in what came to be called Kenya’s northern frontier, a vast arid savannah, woodland and desert that stretched west to the Sudan and north to Ethiopia.

However, by the time the British established their authority over all of the Kenya colony, and especially by the end of WWII, the Darod clans increased their numbers in the northeast of Kenya—in what is now called Wajir, Mandera and Garissa districts. These areas now have a growing and sometimes dominant Somali presence. In 1964, the Somali of northern Kenya fought a 10-year on-and-off guerrilla war against the newly established Kenyan government, in hopes of linking their territory with the newly independent state of Somalia. This strategy did not work.

From the late 19th century onwards, the British bypassed the Swahili, sending in missionaries from the coast to convert the Bantu and Nilotic speaking tribes of the Kenyan interior, these being former victims of the coastal slave trade. The modernizing elites of these groups then fought with the British during WWI and WWII, and demanded independence after the war, which they got. From an ethnographic point of view, what this means is that the descendants of the non-Muslim tribes that formerly provided the coastal Muslims with slaves were now in charge of the government and economy of Kenya, making Muslims to the northeast and on the coast a political minority within the region.

After 9/11, the southwest expansion of the Somali Darod into Kenyan territory took on a new religious dimension. The young men who man Al Shabab and the youngish “imams” who write their fatwas, the religious rulings that encourage them to bomb “infidel hotels” in Nairobi and other places, have broken away from their elders. Their violent nihilism isn’t much different in character from that of rampaging Congolese militias, except they perform their violence under cover of Jihad. But whatever the pretext, the campaign can be classified, as former Governor of Tanganyika and Zanzibar, Sir Richard Turnbull, called it, the “Darod Invasion” of northeastern Kenya.

This Islamic-branded tribal expansion has two goals. The first is to undermine the Kenyan government so that the southwesterly movement of Darod pastoral tribes toward Mount Kenya can continue. The second is to prosecute a blood feud against the descendants of the tribes that the coastal slavers had preyed on in ancient times, thereby reversing the balance of power in the region and bringing back the old order that existed before British warships broke up the coastal slaving networks.

This will never happen. But Al Shabab believes it will, and is willing to kill as many people as necessary to prosecute its terroristic struggle. This is likely not a movement that can be reasoned with. And so the Kenyan government and its allies must do everything possible to destroy it by force, while also seeking a peaceful solution to the ongoing war in southern Somalia, the home of the restive Darod. This might include formally recognizing the independent Somaliland of the north and, with its help, creating a military pincer against the Darod in the south, a strategy that has yet to be tried.

But whichever path Kenya, the United States, the UK, the African Union and other allied forces take, it is important to remember that Al Shabab is more than just a terrorist group. It is the pathological expression of an ancient hatred between tribes and religions that has persisted for centuries, and springs from the roots of a trade whose evils are known only too well to all parts of the African continent.