children

Correcting ‘Youth’s Eternal Temptation to Arrogance’—One Bedtime Story at a Time

Children get a wider perspective when they’re tugged out of the here and now for a little while each day. In an enchanted hour, we can read them stories of the real and imagined past.

“We almost never take this out because it is really fragile,” said Christine Nelson, a curator at the Morgan Library in New York. I was sitting across from her, in her office.

She drew out a small navy-blue case and opened the lid. Inside, its glossy red leather binding embossed with gold, was the earliest surviving volume of the fairy tales of Charles Perrault. This beautiful object had been created in 1695 as a gift for the teenage niece of Louis the Fourteenth, a girl known as “Mademoiselle.”

Nelson opened to the frontispiece (illustrated above), revealing a charming little painting. A plain-faced woman in a linen coif and rustic dress sits before a fire, holding a spindle of wool. She seems to be telling a story to three young people in elegant clothes, one of whom leans forward, touching the storyteller’s knees in her eagerness. Curled up by the fire, a plump little cat listens, too. On the wooden door behind the spindle holder, a sign reads: Contes de Ma Mere l’Oye. (Tales of My Mother Goose!) More than three centuries ago, a careful hand (possibly Perrault’s son, Pierre) had dipped a pen in ink, and in beautiful cursive committed the world’s first known collection of fairy tales to this folio. Now the pages were fragile, crisp, and speckled with age spots.

There I was, sitting in a modern office building, with trucks and cars rumbling up nearby Madison Avenue, and for a fraction of a second the book before me seemed to become a portal, like a wardrobe into Narnia or a portkey at Hogwarts, that could fling me into the past. I had the fleeting idea that if I were to touch the page, I might be flashed back to a place of silks and mirrors and a laughing girl, and that if I were to squint or tip my head at the right angle, I might go deeper still, through the story and out the other side, into the hazy Indo-European folkways where the stories began. It was the impression of a moment, and it was whimsical, I know, but the tales that Perrault collected have such broad cultural resonance today that I felt giddy to be so close to the first Mother Goose.

Charles Perrault is credited with creating the literary tradition of the fairy tale, but of course the stories he told weren’t his. They had come from deep in the trackless past and were, by word of mouth, on their way into the future when he plucked them from the air and wrote them down. He and other collectors and folklorists over the centuries and across the world—enterprising individuals such as Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy, Wilhelm and Jacob Grimm, Andrew Lang, Moltke Moe, Lafcadio Hearn, Charles Chesnutt, W. E. B. Du Bois, and many others—have preserved vast libraries derived from “the golden network of oral tradition” that might otherwise have been lost. Without their efforts, we would have inherited nothing like the richness of story, song, and legend available to us in the digital age.

“If you want your children to be intelligent, read them fairytales. If you want them to be more intelligent, read them more fairytales,” Albert Einstein advised. I don’t know if the great theoretical physicist really made that remark, and I cannot promise that reading fairy tales to a child will tweak his IQ, but there is no doubt that these weird dramas of risk, terror, loyalty and reward agitate the blood and captivate the heart. To C. S. Lewis, time spent in what he called “fairyland” arouses in a child “a longing for he knows not what. It stirs and troubles him (to his lifelong enrichment) with the dim sense of something beyond his actual reach and, far from dulling or emptying the actual world, gives it a new dimension of depth. He does not despise real woods because he has read of enchanted woods: The reading makes all real woods a little enchanted.”

The reading does something else, too. It situates children in a cultural sense, equipping them to understand references to fairy tales and other classic stories that they will find all around them. When we read Hansel and Gretelor The Fisherman and His Wife or Puss in Boots, we’re at once transporting children with our voices and grounding them in foundational texts. For this reason, the time we spend reading to them can amount to a second education, one that helps children “acquire a sense of horizons,” in the phrase of linguist John McWhorter. What we give them is not schooling quaschooling, but an introduction to art and literature by means so calm and seamless that they may not notice it’s happening.

When the Dominican-born writer Junot Díaz was a boy, his elementary-school librarian in the United States showed him around the stacks and told him, he said years later, that “all the books on the shelves were mine.” It was a galvanizing moment that he never forgot. And it is a message that every child needs to hear. Owning something and taking possession of it are two different things, of course. A child may have as much right to Beowulf as the scholar who devotes his life to the study of Old English. Yet unless the child meets the hero Beowulf and the monster Grendel, and Grendel’s gruesome mother, he cannot be said to have taken possession of the property that’s his. Let that child’s mother read Beowulf in translation at bedtime (if she dares—it’s pretty gory), and the child’s custody is complete. The characters and scenes and language of the book will become part of his interior landscape.

The more stories children hear, and the more varied and substantial those tales, the greater the confidence of their cultural ownership. They will recognize allusions that other children may miss. A girl who has heard the stories of Aesop or Jean de la Fontaine will have a clear idea of what is meant by “sour grapes” and will know why people compare the industriousness of ants and grasshoppers. A boy who’s heard a parent read The Odyssey has a more complete idea of what constitutes a “siren song” than his friend who thinks it must have something to do with an alarm going off.

The narratives of the past have helped to frame the consciousness and language of the present, and it’s a gift to children to help them recognize as much as they can. The milk of human kindness, the prick of the spindle, the wolf in sheep’s clothing, the wine-dark sea: all are expressions of a vast cultural treasury.

“We all come from the past, and children ought to know what it was that went into their making, to know that life is a braided cord of humanity stretching up from time long gone, and that it cannot be defined by the span of a single journey from diaper to shroud,” Russell Baker writes in his beautiful memoir, Growing Up.

Children get a wider perspective when they’re tugged out of the here and now for a little while each day. In an enchanted hour, we can read them stories of the real and imagined past. With picture-book biographies we can acquaint them with people we want them to know: Josephine Baker and Amelia Earhart, Julius Caesar and Marco Polo, Martin Luther King Jr. and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, George Patton and Shaka Zulu, Pocahontas, Frida Kahlo, Edward Hopper, William Shackleton, the Savage of Aveyron, and the terrible Tudors.

With any luck, our children will come to appreciate that the people of generations past were as full of life, intelligence, wisdom, and promise as they are, and impelled by the same half-understood desires and impulses; that those departed souls were as good and bad and indifferent as people who walk the earth today. Those who came before us wrote stories and songs, built roads and bridges, invented and created and argued and fought and sacrificed for all sorts of causes. Do we not owe them a debt of gratitude? We wouldn’t be here without them.

Young people are inclined to think, in a vague way, that events began when they did. When I was a child, I was told that President Kennedy was shot in 1963. It seemed to me that the tragedy coincided, more or less, with the end of the Civil War. When you’re young, the decades blur together. Only years later did I come to understand that JFK died six months before I was born, and that I entered a world still shocked by his departure.

So it goes. Youth is inattentive. It thinks itself something fresh, full of energy, spirit, and insight. It feels that no one has ever cared so much, felt with such intensity, or realized truth with such exquisite clarity. It prepares for a future that is unique in its grandeur and meaning. Youth may have no idea that it is wreathed in ghosts, informed by ghosts, held up on the shoulders of ghosts. When we read aloud from the literature of the past—and all literature is the literature of the past—and when we share artistic traditions, we are not merely giving children stories and pictures to enjoy. We’re also inviting a measure of humility, gently correcting youth’s eternal temptation to arrogance.

* * *

It helps that children love the bump and tumble of rhyming words. They may not mind one way or another about the characters of Humpty Dumpty or Little Miss Muffet or Old Mother Hubbard, but most little ones find the lolloping rhythms of nursery songs irresistible. (I have the faintest memories of my mother chanting “Ride a cock-horse to Banbury Cross” to me. Holding my hands, she’d jog me on her knees, as her own mother had done with her. At the crucial line, “And she shall have music wherever she goes!” she’d pretend to drop me, and I’d shriek. This all came back to me with a rush when I saw her do the same with my daughter Molly, as she, Molly, will probably someday do with her own children.)

Fun to chant, and culturally grounding to learn, nursery rhymes also happen to be a terrific entry point to language. Neurobiologist Maryanne Wolf and others believe that exposure to these traditional poems can help to sharpen a small child’s awareness of the smallest sounds in words, known as phonemes. “Tucked inside ‘Hickory, dickory dock a mouse ran up the clock’ and other rhymes,” Wolf writes in Proust and the Squid, “can be found a host of potential aids to sound awareness—alliteration, assonance, rhyme, repetition. Alliterative and rhyming sounds teach the young ear that words can sound similar because they share a first or last sound.”

Fairy tales also encode a measure of philosophical and practical wisdom, as Vigen Guroian observed. It is certainly easy to see the moral precepts in Little Red Riding Hood. Perrault all but spells them out with the ominous sexual overtones in his version of the tale. Having devoured the grandmother and taken her place in bed, the wolf tells Little Red, when she arrives, to undress and join him. She does—to her ruin. In case we missed the metaphor, Perrault makes it explicit in the second half of the moral of the story (the first was at the beginning of this chapter):

And this warning take, I beg:

Not every wolf runs on four legs.

The smooth tongue of a smooth-skinned creature

May mask a rough and wolfish nature.

These quiet types, for all their charm,

Can be the cause of the worse harm.

Viewed in this cautionary light, Little Red Riding Hood seems to come to us a from a long line of parents stretching back in time, all calling, one generation after another, “Watch out! Beware the sweet-talking stranger!”

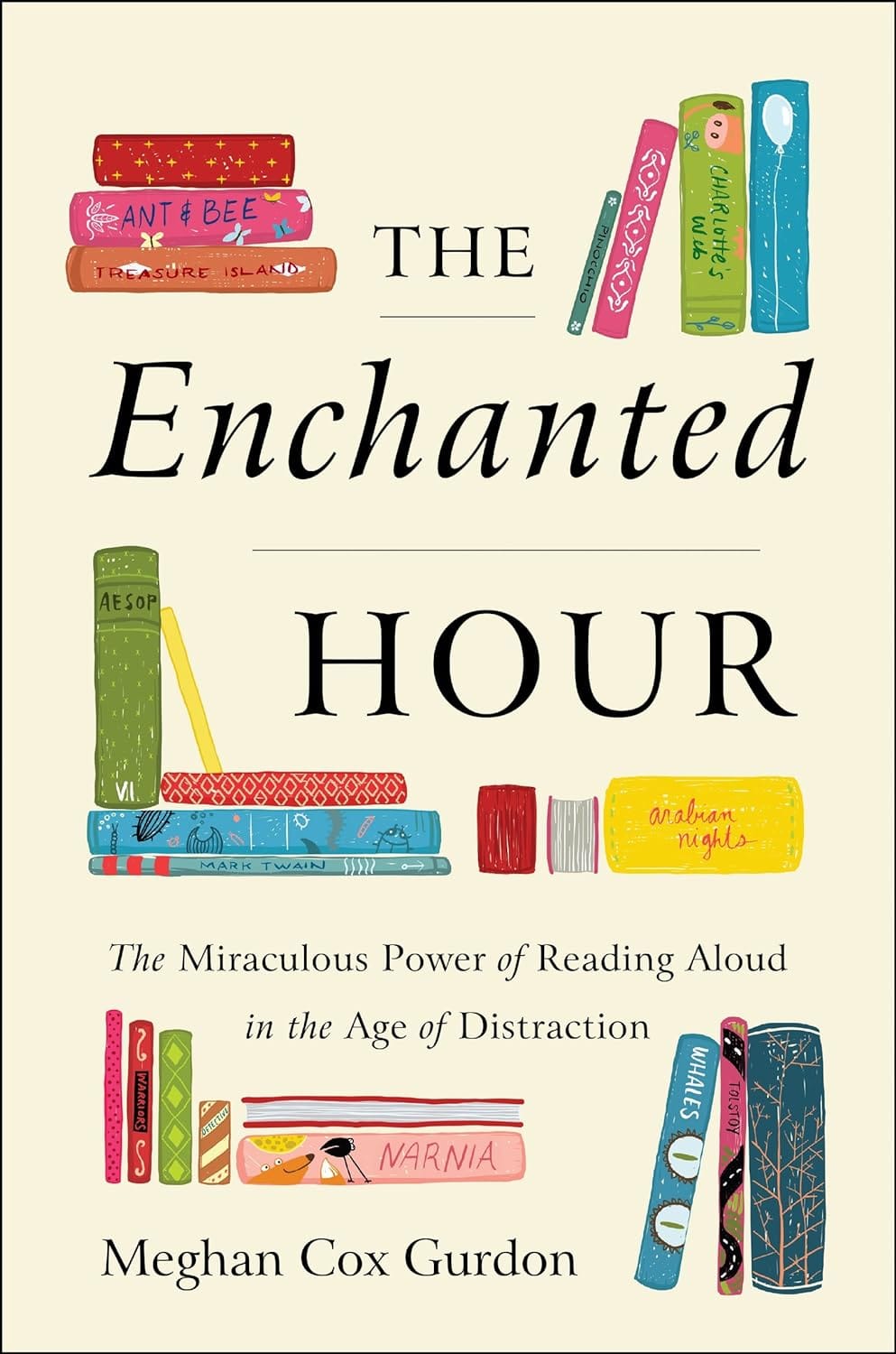

Excerpted, with permission, from The Enchanted Hour: The Miraculous Power of Reading Aloud in the Age of Distraction, by Meghan Cox Gurdon © 2019. Published by Harper. All rights reserved.