History

"Heroic Guerrilla"—From Revolutionary Militant to Saint

Before his corpse was cold, the Che cult had a ready-made logo; a brand. But what exactly does it signify?

In 1954, my father was working for the Guatemalan Ministry of Agriculture as a veterinarian in charge of the artificial insemination of cattle. He was asked if he would like to meet a fellow Argentine—another recent graduate from the University of Buenos Aires, an M.D. named Ernesto Guevara de la Serna. He said sure. They met “almost daily to talk and drink un cafesíto.” Guevara was broke; my father always paid. They talked politics, as any university-educated Argentine of the period would; of the injustice, the poverty, and the callous indifference of the elites to the suffering of the poor. Nothing out the mainstream for the time and place. My father said there was no talk of Marx or guerrilla warfare. Guevara mentioned that he wanted to practice medicine in the countryside, but the Ministry of Health insisted that he join the Communist Party. Ernesto refused and told them that he would not join the Party in order to practice medicine. My father was not required to join the Party, I assume because livestock are not in need of political indoctrination while being inseminated. To him, Guevara was an interesting but not exceptional expat.

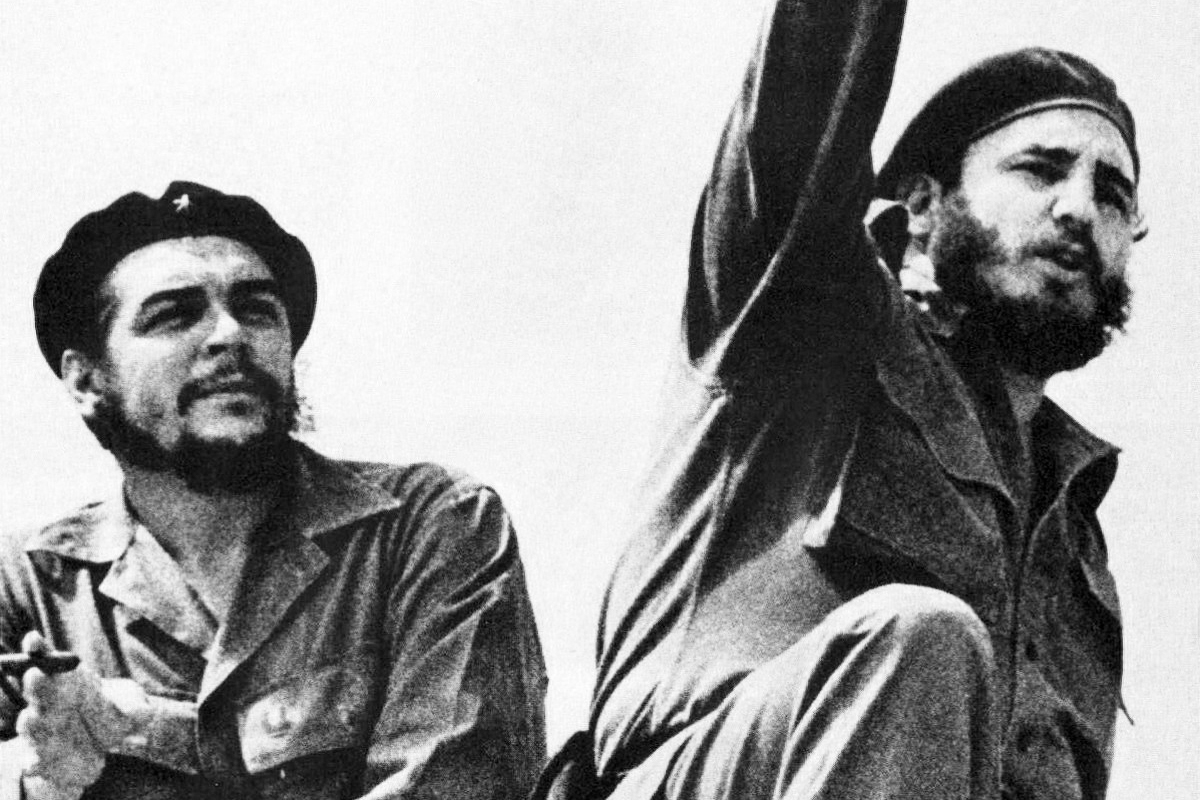

That year, the U.S. orchestrated the overthrow of Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán’s government, which forced Guevara and my father to flee Guatemala—Guevara went to Mexico to meet a Cuban named Fidel Castro and his destiny; my father went to Miami, Florida, to start a family and an import–export business. In 1960, a regular customer of shortwave radio gear, a Nicaraguan, asked if my father wanted to take a trip to Cuba. My father demurred saying he wasn’t in a financial position for such a trip. The Nicaraguan explained that travel expenses would be taken care of by an old acquaintance. My father, with the help of his business partner, secured a $3 million line of credit from a U.S. bank hoping to do some business with the new regime. At La Cabaña Fortress in Havana, Cuba, Guevara—now Commandant Ernesto “Che” Guevara, co-author of the Cuban revolution of 1960—warmly greeted his former coffee drinking companion with a hug. He asked my father to come to Cuba and work. My father made a counter-offer to use the line of credit and begin commerce. Che declined, explaining, “Humberto, we will not do business with the gringos because we can’t trust them.” My father said he would think over the offer and consult with his wife. They parted with an embrace, never to see one another again.

Guevara was executed on October 9, 1967, during his futile attempt to repeat his revolutionary Cuban success in the Bolivian countryside. My father, sometime between the late 1960s and early 1970s, while travelling in the Soviet Union for a U.S. pharmaceutical firm, stood in front of an exhibit dedicated to the martyred guerrilla revolutionary Ernesto “Che” Guevara. The reverence of the exhibit (I have been unable to find any documentation) made a deep impression on my father. “It occurred to me that this is how religions are started,” he related to me many years later.

The Cult of “Che”

The first indication of Guevara’s deification came in the May 17, 1968, issue of Time magazine. The article “Communists: The Cult of Che” chronicled the “cult of almost religious hero worship among radical intellectuals, workers, and students across much of the Western world.” Time reported that students rioting in Europe were carrying his photo, wearing Che-style beards, dark blue berets, and sweatshirts and blouses with his “shaggy countenance,” that “half a dozen books by or about Che have published since his death,” and that at least as many filmmakers were in a race to bring a Guevara biography to the screen. I believe that my father was vaguely aware of the events that followed Guevara’s death, but the exhibition in the U.S.S.R. made the cult of Che tangible in a manner that no news article could have managed.

In fact, the cult of Che began within hours of Guevara’s execution by a Bolivian army sergeant. After his body was placed in the Vallegrande, Bolivia, hospital laundry room, hospital nuns, the nurse who washed his body, as well as several women of the town, had the impression that the dead Argentine resembled Jesus Christ and clipped snippets of his hair to keep for good luck (Anderson, 1997). A photograph in that room, by Freddy Alborta, of Che’s body on a stretcher—head propped upward, eyes open, surrounded by his enemies—bears a passing resemblance to Andrea Mantegna’s “Lamentation over the Dead Christ” (1480).

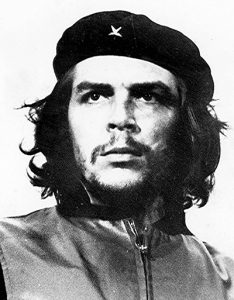

But it would be another photograph—beret with a star, long hair, beard, and faraway look—that would propel Ernesto Guevara onto T-shirts, posters, cups, stamps, and hundreds of other consumer goods. Taken by Cuban photographer Alberto Korda in 1960 at a rally in Havana, and dubbed “Heroic Guerrilla,” an Italian publisher had thousands of posters made and distributed just months before Guevara’s death. Irish artist Jim Fitzpatrick created a stylized version of the photograph shortly thereafter; it is an icon, a symbol, almost as recognizable as the Christian cross or Islamic crescent. But what does it signify? And does it have the wattage to light up the religious circuits of the human mind for the long haul?

Before trying to answer this question, a brief review of Ernesto Guevara’s deeds and words is necessary to refute the idea that he is worthy of beatification. I begin my indictment, as many others do, at La Cabaña, the eighteenth century fort in Havana where my father met Guevara for the last time. Guevara had been named “supreme prosecutor” of the revolutionary “Cleansing Commission”—the euphemism for the show trials of former regime functionaries, mostly lower-level police torturers and deputies, the top men having fled the country or hidden in foreign embassies. The trials began at eight or nine in the evening, a verdict was usually delivered by two or three in the morning, and a firing squad executed the condemned shortly thereafter (Anderson, 1997). Guevara defended the trials and executions, explaining that the people demanded justice. In private, he would tell subordinates that the real reason for the executions was that Arbenz in Guatemala had fallen because he had not purged the armed forces. Guevara was not about to permit the same to happen in Cuba (Anderson, 1997). The body count totals at the La Cabana vary, but if Guevara had had his druthers, it would have been pocket change. When the October 1962 Cuban missile crisis was defused by a Soviet agreement to withdraw the nuclear missiles from Cuba in exchange for U.S. concessions, including a pledge not to invade Cuba, Guevara was furious. He saw it as a monstrous betrayal and, a few weeks later, declared that if the missiles had been under Cuban control, he would have fired them all into the United States (Anderson, 1997). This was not hyperbole, he was serious; Guevara advocated for an atomic holocaust.

In his short book, Guerrilla Warfare: A Method, subsequently translated into many languages, Guevara instructs his readers in the techniques of becoming killing machines. It was studied as catechism by his disciples who went with guns in hand to spread revolution and were martyred in their turn. He hoped for “a bright future should two, three or many Vietnams flourish throughout the world with their share of deaths and their immense tragedies, their everyday heroism and their repeated blows against imperialism.” (Guevara, 1967)

In the years immediately following his death, young people from Montevideo to Berlin followed Che’s example of bloodshed. In language that could be mistakenly attributed to any of the tyrants he had striven to overthrow, he said:

Hatred as an element of the struggle; a relentless hatred of the enemy, impelling us over and beyond the natural limitations that man is heir to and transforming him into an effective, violent, selective and cold killing machine. Our soldiers must be thus; a people without hatred cannot vanquish a brutal enemy. (Guevara, 1967)

It wasn’t just Bolivian peasants that sainted Che, Western intellectuals immediately began to transcribe the Che canon. British author and historian Andrew Sinclair in his 1970 book Che Guevara identifies “the untrue and irrational” elements of the Che cult, specifically the analogy with Christ—a man fighting for the poor, martyred in his youth for all of humanity. Sinclair acknowledges Che was inhuman, a killer who hated, and yet “he transcends all these facts.” Ultimately, Sinclair can’t resist joining the cult:

He appears as larger than a human being, as somebody approaching a savior. When all is said and done, when his words and acts have been coldly seen and sometimes condemned, the conviction remains that Che was always driven by his love for humanity and for the good in mankind. (Sinclair, 1970)

If I understand Sinclair correctly, it was Che’s love of humanity that made him kill as many humans as was necessary to consummate that love. It sounds like the justifications of a domestic abuser.

In the village of Vallegrande, Bolivia, where the captured Guevara was brought, some of the locals pray and attribute miracles to San Ernesto. A nurse who washed Guevara’s body said, “None dies as long as he is remembered. He is very miraculous” (Schipani, 2007). In Cuba, the Afro-Cuban faith Santeria has incorporated Guevara (as a black man) as a divine entity that can, for the supplicant, intercede with God (Alvarez de Toledo, 2010). But it’s the secular world that keeps the Che cult from withering. In 1997, the thirtieth anniversary of his death, five biographies were published; that same year, his remains were discovered in Bolivia and reinterred in a mausoleum in Santa Clara, Cuba, the site of the battle led by Guevara that defeated the former regime and installed Castro and Guevara in power.

The apex of the Che revival, at least at the time of this writing, was in 2004 with the release of the Walter Salles film, The Motorcycle Diaries, based on young Guevara’s travels throughout Latin America (my father and I enjoyed the film together). The Che cannon grows yearly: Chesucristo: The Fusion in Image and Word of Che Guevara and Jesus Christ, a coffee table art book (Kunzle, 2016); a Guevara biography published in 2018 and another to be published in 2019; journal articles such as “Resurrecting Che: Radicalism, the Transnational Imagination, and the Politics of Heroes” (Prestholdt, 2012) and book chapters such as “Desperately Seeking Something: Che Guevara as Secular Saint” (Passariello, 2005) are regularly published by European, U.S., and Latin American academics.

But the cult of Che sustains itself primarily with Korda’s iconic image, Heroic Guerrilla, always front and center and everywhere on earth as journalist Michael Casey chronicles, in his book, Che’s Afterlife: The Legacy of an Image, the origins, permutations, legal battles, and iterations of what is perhaps the most reproduced photo of the 20th century. Casey calls the Korda photo:

...the crucifix for the Church of Che. It’s not for nothing that this image is described as an icon, a word derived from the Greek eikon, which itself means “image” and was first used in the Greek Orthodox Bible in reference to God making man in his image. (Casey, 2012)

Che the Myth

Before his corpse was cold, the Che cult had a ready-made logo; a brand. But what exactly does it signify? From Argentina to Bolivia, the Korda photograph can signify almost anything. For the businessman creator of a tourist trail at the location of Ernesto’s childhood home in the province of Misiones, Argentina, Che embodies the spirit of entrepreneurship. For a Bolivian bottler of a premixed rum and cola drink, Cuba El Che, Che’s image is an instrument of successful marketing. Argentine activists, in preparation for a protest march, guide young people to draw the Korba Che photo on a flag—the image is a totem: “Che is the force in our marches, our actions…We called on him then. He is the one inside of us” (Casey, 2012).

Ernesto Guevara was born, raised, and died in the Latin American milieu of Christianity. The Bolivian women who tended to the corpse of Guevara reported that he resembled Jesus Christ, and not, unsurprisingly, Osiris, Zoroaster, Krishna, or Buddha. As we have seen, many analyses by secular intellectuals of Che instinctively draw on analogues with Christianity and its eponymous divinity. In Latin America, and arguably Western society, the “mythic lore” of Jesus Christ is one the “filaments of myth that are everywhere in the air” acting as magnets to “the great and little heroes of the world” (Campbell, 1964). Guevara’s narrative, in particular his death—the whereabouts of Che’s body was unknown for decades—contains a strong field of mythic magnetism to attach itself to the Christ myth. Joseph Campbell observed in his magnum opus The Masks of God: Occidental Mythology:

For the function of such myth-building is to interpret the sense, not to chronicle the facts, of a life, and to offer the artwork of the legend, then as an activating symbol for the inspiration and shaping of lives, and even civilizations, to come. (Campbell, 1964)

In the same volume, Campbell traces the mythological Levantine antecedents of the god death and resurrection myths adapted in the Christian tradition to a one time historical event, the earliest of which date back to 5500 BCE. For the cult of Che, the Korda photo is the activating symbol to inspire and shape lives. The Che narrative morphed from the historical to the mythological at the speed of light. Che Guevara the myth and icon does possess an activating polarity to propagate a myth for civilizations to come.

When Campbell wrote of the filaments of myths that floated in the “air,” he argued that myth did its heavy lifting in the human mind. He defined a “functioning mythology” as a “corpus of culturally maintained sign stimuli” that catalyze a release of energy. Myth functions as a sign, stimuli triggering an innate releasing mechanism, terms borrowed from ethology, the science of animal behavior:

The reader hardly need be reminded that the images not only of poetry and love but also of religion and patriotism, when effective, are apprehended with actual physical responses: tears, sighs, interior aches, spontaneous groans, cries, bursts of laughter, wrath, and impulsive deeds. Human experience and human art, that is to say, have succeeded in creating for the human species an environment of sign stimuli that release physical responses and direct them to ends no less effectively than the sign of nature the instincts of the beasts. (Campbell, 1959)

Che as God

I will reframe my father’s question; what could keep the cult of Che from becoming a religion? The Ernesto “Che” Guevara narrative, now more mythology than primary source history, and the Korda photo contain an abundance of “sign stimuli.” The cult of Che awaits a Paul to rewrite the passion play and address the questions of mortality, misfortune, and “general order of existence.” In the meanwhile, if you wear a shirt with Che’s image or paint it on a flag, he offers protection, perhaps comfort, and with the proper supplications an active interdiction against injustice.

Gods have their origin in ancestors who climb the mount of deities. Guevara might become the first god of the twenty-first century with universal appeal; he’s got the sex appeal, branding, and martyrdom in the name of the downtrodden. A painting of Che and Guatemalan national hero Tecún Umán (1500?–1524), the last ruler of the Mayans killed in battle fighting the Spanish, greets visitors to a Guatemalan hostel, suggesting that Che is an ancestor to a local tribe and also an ancestor to a modern cosmopolitan tribe. Even his nickname, given to him by Cubans, is appropriate. In Argentina, the word “che” is a term of endearment meaning pal, buddy, or mate.

To my father, this was how religions began, a messianic man kills and is killed and decades, perhaps centuries later, is worshipped as a deity. He was astonished that his path had crossed, however briefly, with such a man. My father didn’t believe in religion; he was critical of the Catholic church in particular. He probably didn’t believe in a god or gods, although I can’t be sure because we never explicitly discussed the topic. I wish he were still around to talk of all these things.

References:

Alvarez de Toledo, Lucia. (2010). The Story of Che Guevara.New York. Quercus Publishing.

Anderson, Jon, Lee. (1997). Che Guevara: A Revolutionary Life. New York. Grove Press.

Casey, Michael J. (2012). Che’s Afterlife: The Legacy of an Image. New York. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group.

Campbell, Joseph. (1959). The Masks of God: Primitive Mythology. N.Y. Viking Press.

Campbell, Joseph. (1964). The Masks of God: Occidental Mythology. N.Y. Viking Press,

Guevara, Che. (1967, 16 April). Message to the Tricontinental solidarity organisation in Havana in the Spring of 1967. The Che Reader, 2005. Ocean Press.

Kunzle, David. (2016). Chesucristo: The Fusion in Image and Word of Che Guevara and Jesus Christ. De Gruyter.

Passariello, Phyllis. (2005). Desperately Seeking Something: Che Guevara as Secular Saint. In Hopgood, James F. (ed), The Making of Saints: Contesting Sacred Ground. Univ. of Alabama Press.

Prestholdt, Jeremy. (2012). Resurrecting Che: Radicalism, the Transnational Imagination, and the Politics of Heroes. Journal of Global History. vol. 7, no. 03, pp. 506–526., doi:10.1017/s1740022812000307.

Redford, Robert. (Executive Producer), & Salles, Walter (Director). (2004). The Motorcycle Diaries. United States. Film Four.

Schipani, Andres. (2007, Sept 23). The final triumph of Saint Che: Forty years after his death in Bolivia, Guevara is a living force in the town where his body was paraded. The Guardian.

Sinclair, Andrew. (1970). Che Guevara. New York. The Viking Press.

Time Magazine. (1968, May, 17). The Cult of Che. 0040781X,, Vol. 91, Issue 20