History

Orwell and the Anti-Totalitarian Left in the Age of Trump

No matter how bitterly they attack one another, they still share many of the same principles and enemies—a fact that should be just as clear to them today as it was a few years ago.

I

In his review of Pascal Bruckner’s new book, An Imaginary Racism: Islamophobia and Guilt, Nick Cohen begins with a denunciation of the contemporary Left’s obsession with identity politics and “willingness to excuse antisemitism, misogyny, tyranny, and obscurantism, as long as the antisemitic, misogynistic, tyrannical obscurantists are anti-Western.” Cohen acknowledges that Bruckner has been among the most penetrating analysts of the Left’s moral and intellectual decline in the twenty-first century, recalling that he described Bruckner’s The Tyranny of Guilt: An Essay on Western Masochism as a “brilliant defence of liberalism and a deservedly contemptuous assault on all those intellectuals who have betrayed its best values.”

However, Cohen now thinks Bruckner’s animus toward the Left has propelled him to the Right, arguing that he fails to “extend his opposition to Islamism to cover the purveyors of anti-Muslim bigotry,” uses the “language of demagogues and civil war,” and displays the “ethnic favouritism and intellectual double-standards of the counter-Enlightenment.” Cohen also laments Bruckner’s sparse commentary on right-wing populist and nationalist movements in Europe and the United States:

At no point would the uninformed reader [of An Imaginary Racism] guess that Law and Justice controls Poland, Fidesz controls Hungary, the Northern League is in power in Italy, and Donald Trump is president of the United States. Meanwhile, if Bruckner shows his concern about Marine le Pen making it to the final round of the French presidential election I must have missed the reference.

In his response to Cohen’s “caustic” and “intemperate” review, Bruckner explains that he doesn’t criticize the Left out of sympathy for the Right—he does so because he expects “more of a Left that was traditionally critical of religion and has now retreated into moral relativity.” Bruckner also points out that it’s possible to be an opponent of right-wing populism and Islamism at the same time: “To believe that we can combat one danger while surrendering to another is to nurse an illusion—this is not the first time in history that we have had to fight enemies on multiple fronts.” But he notes that “my new monograph is not about the rise of European neo-populism … Cohen’s complaint seems to be that I didn’t write a different book entirely.”

These are, to my mind, fair points. It’s misleading to say Bruckner has “accepted the identity politics of the Right,” and there’s no reason to believe he’s trying to “replace the slogan that ‘the West is the root cause of all evil’ with ‘the Left is the root cause of all evil.’” Cohen, meanwhile, is right that anti-Muslim bigotry has been instrumentalized by the Trumps and Le Pens of the world, but it’s also important to recognize that Bruckner’s objections to the misogyny, homophobia, and other forms of illiberalism in many Muslim communities are rooted in values that would (or should) find plenty of support on the Left, such as secularism and pluralism.

While the quarrel between Cohen and Bruckner may seem petty and personal, it highlights a source of tension that has existed for a long time on the Left. Bruckner refers to it directly:

Cohen’s approach to my book reproduces a tactic familiar from the Cold War. Just as we were once instructed that criticising the Soviet Union played into the hands of American imperialism, those who attack Ikhwani, salafi, Wahhabi, and Khomeinist fanatics today stand accused of promoting the interests of the nativist Right. This kind of Stalinist blackmail, as Cohen certainly knows, led generations of progressive intellectuals into cowardly silence and complacent appeasement of totalitarianism.

When left-wingers criticize their own side, they’re always vulnerable to the charge that they’ve betrayed their allies and defected to the Right. Bruckner is correct to point out that this accusation has been weaponized to suppress dissent, but he doesn’t seem to notice that he’s using the tactic on Cohen in reverse. He describes Cohen as an “enlisted journalist” who has abandoned his “eminent dissident’s position” and is now “anxious to reassure his readers that he is still on the Left.” And he seems to think Cohen has repudiated just about every critical word he has written about the Left over the past couple of decades: “Those who militated for 20 years against terrorism, obscurantism, and Islamofascism will be saddened to have lost his support, and may be left to wonder if it was authentic or just a posture.” None of this is true. Cohen is still a lacerating critic of the authoritarian Left, as he makes clear in the review itself.

It’s frustrating to watch two left-wing writers—both of whom have produced imperishable critiques of the Left—disparage and misrepresent one another in print. Despite the very real differences between them (I happen to agree with Cohen that Bruckner should devote more of his energy to resisting the authoritarian Right), they belong to an honorable and endangered political tradition that offers the best guide to maintaining intellectual integrity and moral clarity in the age of Trump and Corbyn.

In the second decade of the twenty-first century, the term “anti-totalitarian Left” seems like a relic from a more heroic era—a grand anachronism that sounds out of place when most of the fascists in the world are tiki torch-wielding idiots in white polos and when most of the West’s remaining communists wear ski masks and throw bottles at Milo Yiannopoulos. But if you take a moment to reflect on a few of the most consequential political debates of the past 20 years—about, say, going to war to remove a genocidal dictator in Iraq, resisting theocratic violence and repression from Paris to Tehran to Nairobi, and responding to anti-democratic movements in Europe, the United States, and South America—you’ll see that the anti-totalitarian (or at the very least, anti-authoritarian) Left is far from irrelevant. Cohen and Bruckner should know: they’re both part of it.

II

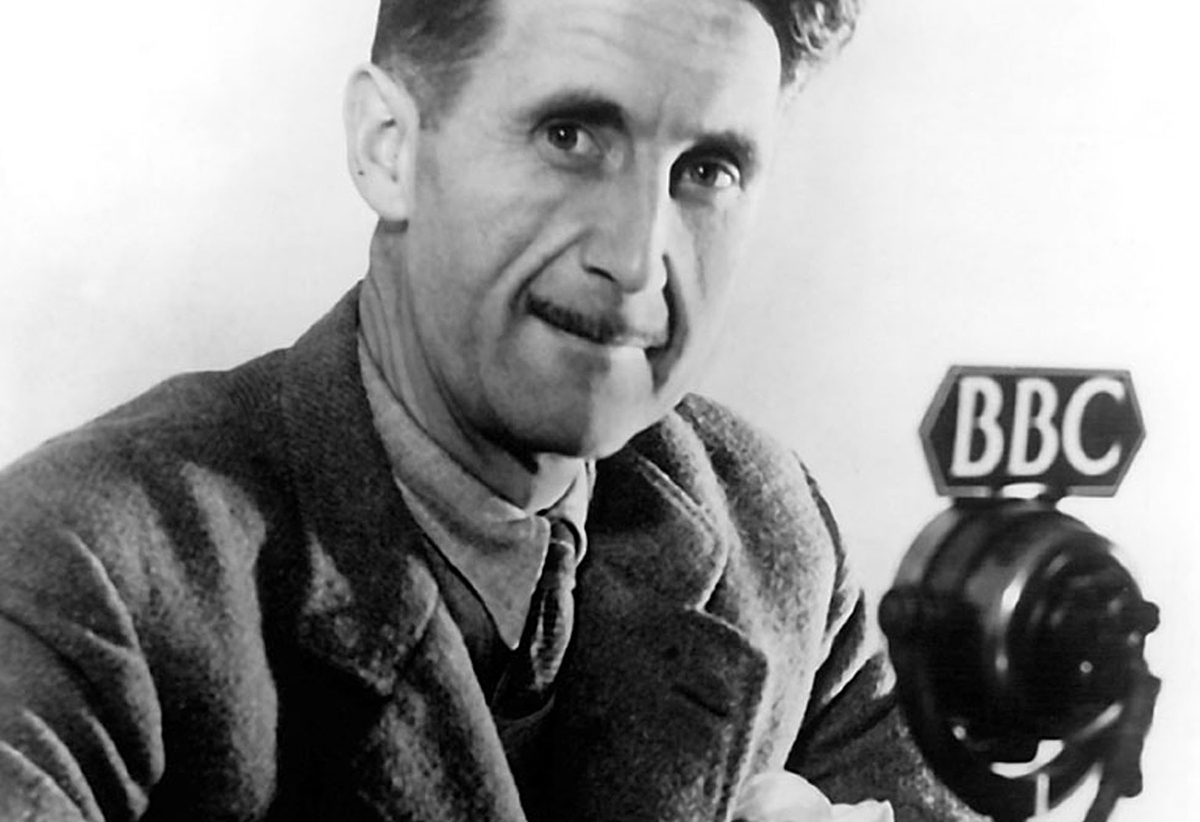

Bruckner’s remark about “Stalinist blackmail” calls to mind a writer whose commitment to both left-wing politics and anti-totalitarianism never wavered in the face of threats and coercion from the Left.

In the summer of 2003, the BBC aired George Orwell: A Life in Pictures. About halfway through the documentary, Orwell (played by Chris Langham) says, “Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism.” This is a line from one of Orwell’s best-known essays, published in 1946, “Why I Write.” But astute viewers may have noticed that something was missing from the reference—eight words that the producers decided to leave out.

Here’s the original sentence: “Every line of serious work that I have written since 1936 has been written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism, as I understand it.” After the sentence abruptly ends with the word “totalitarianism” in the documentary, Langham takes a long drag on his cigarette before jumping to a different passage of the essay. It was almost as if the producers wanted to accentuate the omission, taunting viewers with their own version of Orwell—one who didn’t have the courage to disclose his true beliefs.

There’s something simultaneously fitting and perverse about the manipulation of Orwell’s words more than half a century after his death (by the BBC, no less). Orwell’s anxiety about the falsification of history is one of the major themes of Nineteen Eighty-Four—as well as much of his other writing and later correspondence—and this is what the producers of the documentary were guilty of doing when they amputated one of his firmest ideological declarations and turned it into a much more palatable and anodyne comment on totalitarianism. No matter how badly some people want Orwell to be a polished and uncontroversial product for mass consumption, he was still the man who wrote these words as he speculated about the possibility of violent revolution in England: “I dare say the London gutters will have to run with blood. All right, let them, if it is necessary.”

Even when Orwell wasn’t in a mood that had him impatiently looking forward to the day “when the red militias are billeted in the Ritz,” he was always honest about his political beliefs. On November 13, 1945, Katharine Stewart-Murray, the Duchess of Atholl, wrote to Orwell asking if he would speak on behalf of an anti-communist organization called the League for European Freedom. This was a month after the publication of Animal Farm—a time when Orwell was worried that the book would be misinterpreted as a broadside against socialism instead of a narrower attack on Stalinism.

Given this context, it isn’t surprising that Orwell declined the duchess’s offer: “Certainly what is said on your platforms is more truthful than the lying propaganda to be found in most of the press, but I cannot associate myself with an essentially Conservative body which claims to defend democracy in Europe but has nothing to say about British imperialism.” Even though Orwell was a staunch anti-communist, his essential political convictions remained immovable: “I belong to the Left and must work inside it, much as I hate Russian totalitarianism and its poisonous influence in this country.”

Orwell was a socialist until the end of his life. For many people, this complicates his legacy and detracts from his pristine image as the twentieth century’s foremost foe of totalitarianism—an image that has been appropriated again and again over the past 70 years.

As John Rodden explains in George Orwell: The Politics of Literary Reputation, in the decades following Orwell’s death, there was an “increased number of claimants and the heightened determination of would-be political beneficiaries to gain exclusive possession of the Orwell halo.” Prominent conservatives and neoconservatives (such as Norman Podhoretz and Irving Kristol) were among these opportunistic claimants, and Rodden criticizes them for “downplaying [Orwell’s] pamphleteering for an ‘English socialist revolution’ during World War II and his expression of support for the Labour Party even after the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four, among their other omissions or distortions.”

It’s not mysterious why the Right is constantly trying to claim Orwell as its own. He pointed out that Stalin was a mass murderer and communism was a deadly sham even when the Soviet Union was aligned with Britain during World War II (which earned him the ire of his compatriots—particularly those on the Left—who thought he was hampering the war effort). He embraced the “patriotism and military virtues” that many “enlightened” left-wing intellectuals sneered at. He despised the “one-eyed pacifism that is peculiar to sheltered countries with strong navies.” And even in The Road to Wigan Pier—a book in which Orwell declares that “Socialism is such elementary common sense that I am sometimes amazed that it has not established itself already”—he excoriates socialists as a bunch of pompous social climbers and cranks who are completely detached from the actual working class.

But as Orwell was at pains to demonstrate (especially after the publication of Animal Farm), he would have firmly rejected the Right’s attempts to appropriate his legacy. While Orwell is rightly celebrated for his refusal to accept the dogmas of the Left when he was under tremendous pressure to do so, his independence of mind is only one of the reasons why he remains so relevant today. His ability to maintain that independence without sacrificing his most fundamental principles may be even more important.

III

Today, the Left could still use some serious Orwellian introspection. Identity politics is steadily eroding its commitment to basic principles like individual rights and free expression. Words like “fascism” and “racism” are on an endless high-decibel loop, driving many former allies (such as the now-reviled members of the white working class) toward populist and nationalist demagogues like Donald Trump. Celebrated cultural and political leaders like Linda Sarsour, Tamika Mallory, and Cameron Perez (who organized the Women’s March, the largest protest in U.S. history) purport to be courageous opponents of racism and fascism while embracing Louis Farrakhan—a noxious anti-Semite who accuses “Satanic Jews” of controlling the media, the government, and…well, you know the rest.

Things are even worse on the other side of the Atlantic. Jeremy Corbyn (the leader of the British Labour Party and one of the most influential left-wing politicians in the world) trumpets high-minded left-wing ideals like solidarity and pacifism, but always ends up making excuses for Russian expansionism, jihadism, and other forms of naked aggression. And, like the organizers of the Women’s March, Corbyn can’t seem to stop defending and associating with anti-Semites. Corbyn’s communications director, Seumas Milne, meanwhile, is a pro-Russia hack who reflexively blames the West for every crime Vladimir Putin commits.

Despite all the evidence that something is very wrong on the Left, with so many right-wing villains like Trump, Viktor Orbán, and Jair Bolsonaro to resist, many left-wingers see no reason to turn their criticism inward. This is problematic precisely because the Trumps, Orbáns, and Bolsonaros of the world are so dangerous. They’ve cynically exploited racial and cultural grievances to attract millions of economically and socially disillusioned supporters. They tell endless lies about the economy (no, globalization and automation can’t be halted), immigration (no, George Soros doesn’t subsidize immigrant “invasions”), international institutions (no, the Paris Climate Accord wasn’t an elaborate scheme to humiliate and rob the United States), and just about everything else. And they have no respect for democratic norms and institutions, which is why their behavior is often overtly authoritarian.

These are all reasons why we’re in urgent need of a broad-based, principled, and rational critique from the Left. But this means we need honest criticism of the Left by the Left as well, which is difficult to come by in an era of bitter political acrimony and soaring polarization.

Recall what Orwell said in his letter to the Duchess of Atholl: “I belong to the Left and must work inside it…” While many on the Left regarded (and still regard) Orwell as a covert reactionary who secretly worked against his own side, this argument simply can’t be reconciled with his scorching rebukes of class privilege, economic inequality, and imperialism—nor can it contend with the fact that his ideological sympathies were evident throughout his life. As much as it annoys some cranky left-wingers, it ought to be clear that Orwell only criticized the Left because he wanted to strengthen it.

IV

In his 2007 book What’s Left? How the Left Lost its Way, Nick Cohen revived this project for the twenty-first century. He asked why the Left—which used to regard international solidarity as one of its core principles—couldn’t seem to muster a whole lot of sympathy for, say, the women’s movement in Iran or the anti-Baathist socialists who had been suppressed and murdered by Saddam Hussein. He asked why left-wing intellectuals like Noam Chomsky always found a way to blame the West for the ghastly crimes of dictators and ethnic cleansers—from Pol Pot to Slobodan Milosevic. And he lamented the Left’s descent into identity politics at a time when the bottom of the plunge was still a long way off (it is possible that we still haven’t reached it yet).

Almost a decade before right-wing nationalist and populist movements swept across Europe and the United States, Cohen explained how identity politics was fueling this process:

In the twentieth century, the workers had been the exploited producers of wealth whose emancipation would herald a glorious future. By the twenty-first, its male members were sexist, racist homophobes; cultural conservatives suspected of harboring unsavory patriotic feelings. They went from being the salt of the earth to the scum of the earth in three generations, and as Thatcher and Reagan had shown, when the liberals despise the working class the opportunities for backlash politics are endless.

Even Cohen couldn’t have foreseen that this backlash would put Donald Trump in the Oval Office, but it would be difficult to find a more accurate analysis of the shifting political and social dynamics that made his presidency possible.

In 2008, What’s Left? was shortlisted for the Orwell Prize—an appropriate honor for a book so firmly rooted in the Orwellian tradition of left-wing self-criticism. Cohen’s critique is so powerful and enduring because he isn’t a David Horowitz-type radical-turned-conservative. When public intellectuals abandoned communism and socialism in the mid- to late-twentieth century, they often did so with the fiery ideological zeal of religious converts—they had seen the light, and it illuminated the moral and intellectual bankruptcy of their old ideas. This meant they were more interested in defeating the Left than improving it. Cohen, on the other hand, has publicly disowned the Left several times, but many of his attitudes and positions—from his castigation of the pro-Brexit Right in Britain to his condemnation of the nativist, authoritarian Right from Hungary to the United States—prove that he’s still an authentic left-winger.

Cohen isn’t the only critic of the Left whose left-wing principles remain intact. One of the most incisive chroniclers of the deterioration of the Left in the twenty-first century is Paul Berman, whose 2003 book Terror and Liberalism convinced Cohen to reevaluate his political allegiances. Berman has spent years confronting the Left about its failure to uphold liberal values in the face of “anti-liberal insurgencies”—particularly violent and repressive movements led by Arab nationalists and Islamic fundamentalists. He has argued that these insurgencies are almost always apocalyptic, antisemitic, and “entranced with slaughter for slaughter’s sake,” which is why he describes their leaders as the “heirs of the twentieth-century totalitarians.” Terror and Liberalism makes the case for treating them as such and resisting them without apology.

The late Christopher Hitchens supported the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and he detested left-wing intellectuals (such as Chomsky, Norman Finkelstein, Chris Hedges, and Tariq Ali) who “masochistically” insisted that terrorist atrocities like 9/11 and 7/7 were ultimately the fault of Western foreign policy. But this didn’t stop him from lambasting the Bush administration’s use of torture or becoming a plaintiff in an ACLU lawsuit against the NSA for its Terrorist Surveillance Program. Hitchens was a lifelong secularist and atheist who spent decades fighting the religious Right. But his hostility to Islamic authoritarianism and violence didn’t prevent him from criticizing Mark Steyn for downplaying the fact that “many Muslims actually have come to Europe for the advertised purposes—seeking asylum and to build a better life.”

Even Hitchens’s support for the Iraq War was grounded in his solidarity with the Kurds—a longstanding cause of the Left—who suffered decades of monstrous abuse under Saddam Hussein, culminating in the genocidal Anfal campaign in the late 1980s (which saw entire towns gassed and left more than 180,000 dead). Despite all the attempts to portray him as a vicious reactionary for supporting wars that were unpopular on the Left, Hitchens’s left-wing principles were indisputable. Is it any wonder that Orwell was his biggest influence?

All of these writers—Cohen, Bruckner, Berman, and Hitchens—are part of what could be described as the contemporary anti-totalitarian Left. While the Bruckner-Cohen dispute proves that this group is far from homogeneous, its members share an essential set of convictions and goals that could reanimate a Left that has become increasingly alienated from its liberal traditions. Many of these convictions and goals were laid out over a decade ago in a document called the Euston Manifesto—an attempt to bring the modern Left into closer alignment with its “authentic values,” as well as a repudiation of “currents that have lately shown themselves rather too flexible about these values.” The manifesto was written by the late Norman Geras, with assistance from Damian Counsell, Alan Johnson, and Shalom Lappin.

The Euston Manifesto provides an ideological framework that places anti-authoritarianism, internationalism, secularism, free expression, and the promotion of universal human rights at the center of left-wing politics once again. It also explicitly condemns the elements of the Left that accept moral and cultural relativism, offer an “apologetic explanation” for oppressive and reactionary movements and regimes, establish “disgraceful alliances … with illiberal theocrats,” regard 9/11 as “America’s deserved comeuppance,” and “entertain openly anti-Semitic speakers and … form alliances with anti-Semitic groups.” All of these critiques are every bit as relevant today as they were in 2006—perhaps even more so.

One of the Western Left’s greatest strengths is its inexhaustible capacity for self-criticism. While this has led to countless schisms and disfigurations over the decades, it has also prevented the Left from surrendering to its worst impulses and dogmas. There will always be someone who remains stubbornly committed to its older and higher principles—some dissident writer or politician who refuses to mindlessly adopt what Orwell called the “smelly little orthodoxies” of the day.

Many of the people who insist that the Left is irredeemable are happy to invoke Orwell. Here was a man who saw through the bloody lie of communism and loathed the hypocrisy and sanctimony of the middle class socialists who would plug their noses if they actually had to spend a few minutes with a coal miner or a tramp. A man who felt a “faint feeling of sacrilege not to stand to attention during ‘God Save the King’” and whose heart “leapt at the sight of a Union Jack.” A man who received a fascist bullet in the throat in Spain and barely escaped Stalin’s agents on his way out of the country. Yet he remained, until the very end, a man of the Left—a man who belonged to a noble political tradition that demagogues and ideologues like Trump and Corbyn are trying to extinguish.

Cohen and Bruckner should get back to the business of reigniting it. No matter how bitterly they attack one another, they still share many of the same principles and enemies—a fact that should be just as clear to them today as it was a few years ago. A decade after the publication of the Euston Manifesto, Cohen reviewed how well the attempt to “revive left-wing support for internationalism, democracy, and universal human rights” had fared over the years. After admitting that it had been a “noble failure,” he nonetheless argued that the manifesto’s signatories “were telling the truth when we warned that dark movements were rising across the Left.” They were, and those movements haven’t gone anywhere.

But Cohen’s Euston postmortem also included a line that he may want to revisit: “For all their professed principles, our critics believed that the fight against misogyny, tyranny, homophobia, racism, and theocracy was a fight no good leftist or earnest liberal could undertake without the risk of conservative contamination.” He should ask himself: Has Bruckner really succumbed to conservative contamination? Or is he still a good leftist, an earnest liberal, and a battle-tested ally in the fight to come?