Canada

The Flawed History and Real Torment of Canada's Residential Schools

Brian was just one of thousands of Indigenous children who were subjected to horrendous abuse at Canada’s Indian residential schools.

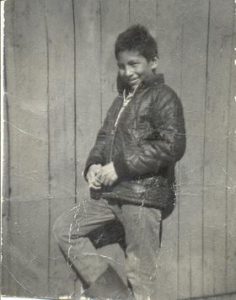

Brian Tuesday was a little Ojibway boy when he was taken from his home at the Big Grassy River Indian reserve and moved to St. Margaret’s Indian Residential School at Fort Frances, Ontario, on the Canadian side of the Rainy River.

Like many of Canada’s notorious residential schools, St. Margaret’s was situated in a large, imposing building. It was built at the edge of a river, adjacent to Our Lady of Lourdes Roman Catholic Church.

The boys and girls were separated in the yard by a wire fence. Brian, whose Ojibway spirit name was Tibishkopiness, wasn’t allowed to approach the fence to talk to his little sister. On more than one occasion, he stood helplessly on his side and watched as one of the nuns beat her for some real or imagined indiscretion.

During the time he was at St. Margaret’s, Brian was sexually abused by a priest and beaten by a nun. Things got a bit better when they transferred him to St. Joseph’s Indian Residential School in Thunder Bay, Ontario—about 350 kilometres to the east, on the north shore of Lake Superior. The sexual abuse stopped. However, a big nun would beat him with a yardstick. She broke his right forearm once when he held it up to ward off the blows.

These horrors would haunt Brian throughout his unhappy life, during the latter years of which he and I became friends. His sense of self-loathing was so strong as an adult that he couldn’t stand the look of the tortured face staring back at him in washroom mirrors, and sometimes would smash the glass with his fist. Despite earning a Bachelor of Social Work with a major in English from the University of Toronto, he never adapted to life in the white world (which was supposed to be the mission of residential schools) and fought a never-ending battle with alcoholism. Brian was just one of thousands of Indigenous children who were subjected to horrendous abuse at Canada’s Indian residential schools. Their gut-wrenching testimony to Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission is enough to break any heart.

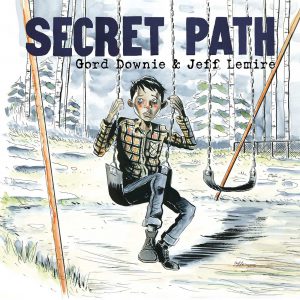

Given such well-documented tales of abuse, one might ask, why are Canadian publishers, educators and even politicians choosing to focus on one of the few residential-school stories that is known to be untrue? Why has Charlie Wenjack, an Ojibway boy who wasn’t even enrolled at an Indian residential school at the time of his tragic death in 1966, become a poster child for all the real wrongs that took place at these institutions? In particular, children in more than 40,000 classrooms across Canada are being told a fabricated tale, as encoded in a massively popular 2016 illustrated book called Secret Path, with substantial financial support provided for the project by Justin Trudeau’s federal government.

Secret Path Week begins this Wednesday, October 17th! Please join us in celebrating the legacies of Gord Downie and Chanie Wenjack from October 17-22 during our 1st Annual Secret Path Week.

— Downie Wenjack Fund (@downiewenjack) October 16, 2018

Find out about events happening in your area this week visit: https://t.co/IKw9HUcIwL pic.twitter.com/jscGtn9JBC

Charlie was born in 1954 at the remote fly-in community of Ogoki Post in northern Ontario. When the boy was nine, he was sent to Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School on the outskirts of Kenora, at the northeast corner of Lake of the Woods, which then was owned and operated by the Women’s Missionary Society of the Presbyterian Church in Canada. His father, who attended the local Anglican church and supported his family by trapping, wanted his son to be educated in the ways of white people.

It took about an hour on a plane and more than 10 hours by train to travel the 600 kilometres from Ogoki Post to Kenora. Like the school my friend Brian Tuesday attended near Fort Frances, Cecilia Jeffrey was run out of a large building on the edge of a lake, and accommodated about 150 children.

This period of Charlie’s childhood is the focus of the aforementioned book, Secret Path, which was authored by legendary Canadian rock musician Gord Downie (who died the year after the book was published) and illustrated by well-known cartoonist Jeff Lemire. (Downie also recorded a concept album with the same name.) The book quickly attained canonical status on Canadian school reading lists, despite containing many significant errors.

Residential schools typically were run according to the precepts of whatever Christian denomination was charged with administering each facility. Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School was Protestant. But for reasons unknown, Secret Path transformed it into a Catholic institution, complete with nuns in habits delousing naked Ojibway boys, a priest dragging a crying girl into a building, a boy in pyjama bottoms yelling in pain as a nun pulls his ear, a priest watching boys taking a shower—and a priest depicted explicitly as a pedophile. Such horrible scenes and details were hardly unknown to the residential-school system as a whole. But there were no nuns or priests at Cecilia Jeffrey. And the staff did not wear clerical garb.

Secret Path shows Charlie looking anxiously from under the blankets at a priest standing in the dormitory doorway. There’s a close-up of his fearful face followed by one of the priest’s crotch. The fingers of the priest’s left hand reach out for him. As a shivering Charlie stumbles along the railway tracks in a doomed attempt to reach his home hundreds of kilometers away, he sees an imaginary pedophile priest watching menacingly from the trees.

Gord Downie’s song lyrics on the page are as follows:

I heard them in the dark

Heard the things they do

I heard the heavy whispers

Whispering, ‘Don’t let this touch you’

To repeat an important point: Sexual abuse was tragically common at many residential schools. But there’s no evidence Charlie was sexually abused by any member of the Cecilia Jeffrey staff, let alone by a Catholic priest. And by falsely presenting Charlie’s life, Secret Path unwittingly does a disservice to the memory of Brian Tuesday and all the many other innocents who truly were abused in Canada’s residential-school system. In the name of “reconciliation,” Canadians rightly have been asked in recent years to come to terms with the predations inflicted on the country’s Indigenous peoples. But if false information is used to further that effort, the entire effort will be held in suspicion.

* * *

When I interviewed Brian 11 years ago in Nestor Falls, Ontario—about an hour’s drive north of the Canada-U.S. border—he was 63, and expressed pride that, despite all the demons that haunted him, he’d stayed almost entirely sober for 18 years. He was in pretty good shape. Still living on the edge, but sober, and mindful of the complex and paradoxical ways that the residential school system contaminated his outlook.

“I was a drunk,” he told me, “I didn’t care what was happening down in the next house or the condition the kids [he had three sons and a daughter] were in. I just didn’t give a damn because there was this notion that I was above all that. Even though I was abusing alcohol at the time, I still believed that I was above it all because I was educated in a white man’s system and I was knowledgeable and doing a lot of things. That was the attitude.”

“Drinking is one of the characteristics of a colonized person,” he had come to believe. “That’s just the way it is and we have to get over that. First, we have to understand that we’re colonized. The way we think has been induced by the colonization process, and now we have to get back to our own [Ojibway] way of life. For a long time, in high school and all that, I denied my own people. And then, when I first went to a sweat lodge, there was a change in my head in the way I used to think, the way I conducted myself.”

Brian told me that he was essentially enslaved by liquor: “You don’t care about anything. You have a bottle and the next drink is all that matters. I’ve been through all that but I’ve also learned a lot from my past. Destroying your body is not the answer to a good life. Destroying your mind, your spirit. That’s essentially what addiction’s doing.”

Across Canada, there are thousands of Indigenous men and women like this, living lives of quiet pain, grappling with the legacy of residential schools. Their names are not widely known, but every one of them could be the subject of their own— truthful—version of Secret Path.

* * *

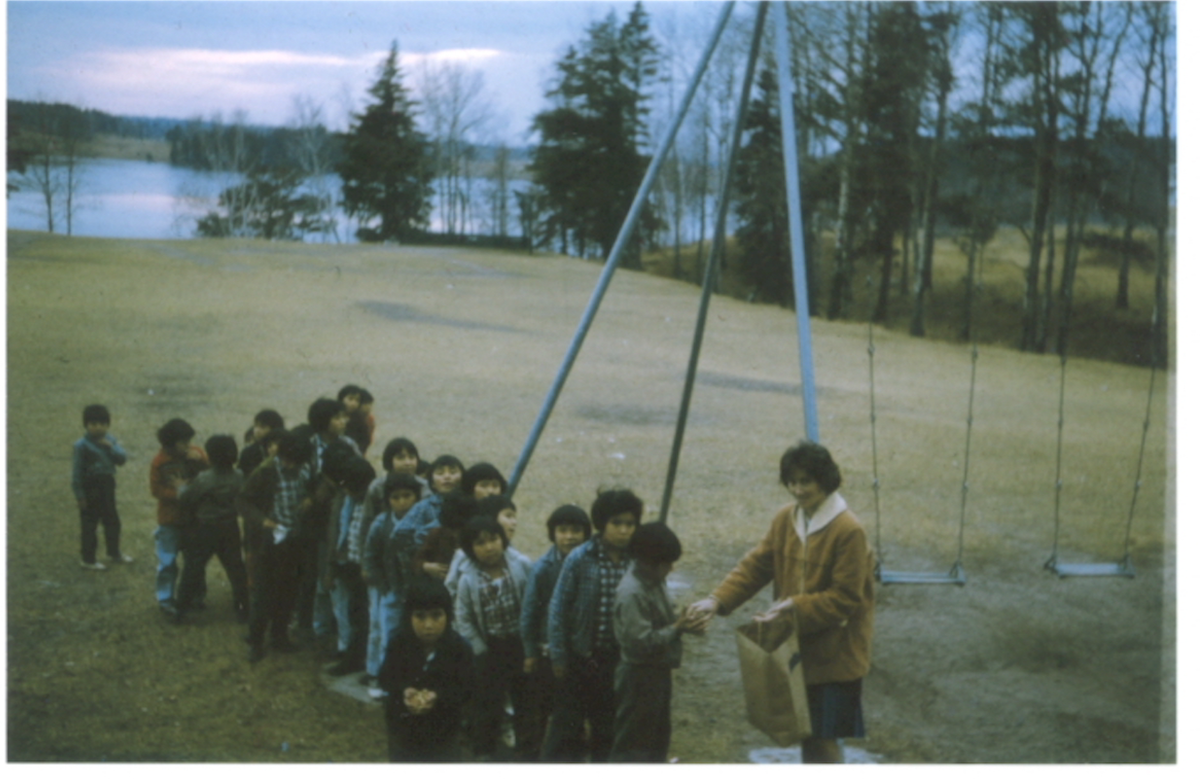

On the sunny afternoon of Sunday, October 16, 1966, 12-year-old Charlie Wenjack was on the swings in the playground of Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School with two orphans—the MacDonald brothers—whose parents had been run down by a train just two years earlier.

At the time, Cecilia Jeffrey was only teaching grade-one students—children much younger than Charlie. However, Charlie and the MacDonald brothers were still boarding at Cecilia Jeffrey while attending Valleyview Public School (where most of the students were white), about a 10-minute walk away. Colin Wasacase, a part-Cree, part-Saulteaux man from Saskatchewan who attended residential schools as a child and taught at two of them as an adult, was in charge.

One of the orphaned brothers whom Charlie sat with on the swings had run away three times in the previous few weeks. The other played hooky on a regular basis. Charlie, by contrast, reportedly had made no attempt to run away during the three years he was at Cecilia Jeffrey—although he did play hooky one afternoon a week earlier.

The MacDonald brothers decided to take off for their uncle’s cabin, which was about 30 kilometres away. Charlie’s best friend, Eddie Cameron, testified at the inquest into his death that Charlie was lonely and, when the brothers left, he went with them. Nothing had been planned. The decision to leave apparently was made on the spur of the moment.

On that first day, after walking for a little more than eight hours, Charlie and his friends reached the home of a non-Indigenous man the brothers knew, who gave them something to eat and let them sleep on the floor. The next day, they arrived at the uncle’s cabin, where the man lived with his wife and two teenage daughters. Eddie Cameron, who was a cousin to the MacDonald brothers, joined them later that day.

According to a November 17, 1966 article in the Kenora Daily Miner and News, “there [at the Ojibway uncle’s cabin] they were fed, cared for and enjoyed trips to a trap line with the uncle. After a few days, the Wenjack lad took his departure and started to walk along the single-track [Canadian National Railway] right of way.” This was five days after Charlie had been playing with his friends on the swings at Cecilia Jeffrey— the image used on the cover of Secret Path (except he is shown by himself).

The orphans’ uncle, Charles Kelly, had showed Charlie how to get to the tracks, and told him to ask railway workers for food along the way. That was the last time anyone is known to have seen Charlie Wenjack alive. His frozen body was found alongside the tracks two days later. He’d walked less than 20 kilometres through snow squalls and freezing rain wearing light, soaked-through, cotton clothing. A month later, a coroner’s jury properly found that Mr. Kelly should have notified the authorities rather than turning the little boy loose in bad weather without any clear idea of where he was going.

There was evidence that Charlie had stumbled and fallen along a rough stretch of railway clearing. He had bruises on his shins, forehead and over his left eye. His stomach was empty. He’d been dead for about a day. It was a truly tragic end for this little Ojibway boy, who was given no choice but to live 600 kilometres away from his home, which is presumably where he was trying to get to when he died.

A text on the back cover of Secret Path tells readers that Charlie died “trying to escape the Cecilia Jeffrey Indian Residential School.” That sounds dramatic. But there were no prison-like conditions from which Charlie, or any other student, would have had to “escape”. The children were free to wander at will. And they did. In fact, Principal Stephen Robinson, who served from 1958 until summer, 1966, shortly before Charlie’s death, reportedly would leave sandwiches in the bush so wandering children wouldn’t go hungry. He knew that most of them would be back in time for supper.

* * *

Of course, there are all sorts of books and movies that fictionalize real historical narratives for dramatic effect. What is unique in the case of Secret Path is that it is a plainly untrue story that is nevertheless being held up as an important learning resource by public institutions. For instance, the Manitoba Teachers’ Society, the provincial trade union for that province’s teachers, tells its members that Secret Path “chronicles the story of [Charles] Wenjack, a 12-year-old boy who died after running away from Residential school in the 1960s,” and has used the book as a basis for educators from across the province to “discuss and explore the Secret Path, and to create lesson and unit plans to support the use of this resource for the teaching about Residential schools in Manitoba classrooms.”

Secret Path by Gord Downie becomes part of Alberta's education resource package https://t.co/6nMYrXUHaE

— Windspeaker (@windspeakernews) October 29, 2017

As part of this project, Manitoba students in Grades 1 through 3 are asked to contrast their classrooms with what is purported to be Charlie’s classroom in Secret Path. However, Charlie wasn’t attending class at Cecilia Jeffrey when tragedy struck: As noted above, he was enrolled in a nearby public school. Students also are asked to note, on the basis of the illustrations in Secret Path, that there are no “toys” in the classroom (as if toys would be part of a normal classroom setting for 12-year-olds). In the same vein, students are asked to discuss “the expressions on the children’s faces.” However, every child in Secret Path’s fabricated classroom is drawn as expressionless and emotionally blank, their arms hanging lifeless at their sides, eyes shut tight as if waiting for someone to whack or rape them.

* * *

Charlie’s older sisters Pearl Achneepineskum and Daisy Munroe visit schools across Canada and, by their presence, have put their stamp of approval on Secret Path. During a 2017 visit to Toronto’s Dundas Junior Public School, Pearl told a reporter she wasn’t sure the students could handle the pictures in Secret Path. But she assured a Global TV interviewer that “even though [images] are very graphic, they do tell the truth. Whoever did this got the real picture of what happened.” Yet Ms. Achneepineskum must once have known—even if she now has forgotten—that there were no nuns or priests at Cecilia Jeffrey, because she was there until she was 17. Ms. Achneepineskum also knows her brother was attending a public school in Kenora and only boarded at Cecilia Jeffrey during the period in question.

If Secret Path had been based on the true story of Brian Tuesday, then graphic pictures of this type would have been quite accurate. They could have shown a nun beating the author, the priest sexually abusing him, and all the rest. But the book isn’t about Brian. It’s about a little Ojibway boy who lived and died tragically, but not in the way that Secret Path claims. Such misrepresentations are unfair to everyone, including Charlie himself, who deserves to have his story told truthfully, to not be treated as a sort of historical mascot, and to be known by his real name as it’s engraved on his headstone: In Loving Memory, Son, Charles Wenjack, 1954-1966.

* * *

Brian Tuesday’s life took a turn for the worse in 2008 when someone suggested he file a claim as a survivor of the Indian residential school system through the Independent Assessment Process—a component of the $2-billion Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement the Canadian government signed in 2007.

While preparing his submission with his lawyer, all of the horrible childhood memories of sexual and physical abuse buried deep in his consciousness bubbled up to the surface. He started drinking again. Heavily. While he was awarded $179,000 in compensation for the abuse he suffered in residential schools, he didn’t derive a nickel’s worth of benefit from it.

He was still drinking heavily when he got the settlement cheque and handed the money over to his ex-wife who lived just up the road at the Sabaskong reserve—about halfway between Kenora and Fort Frances. She bought herself a Buick SUV, got a new boat and built a porch around her house.

When I last saw Brian, in September, 2010, he was flat broke and gaunt, surviving on fish he got from a commercial fisherman he helped out every morning. I gave him a ride to Fort Frances to visit one of his sons, who had been in and out of hospital for several years. Brian’s long white-streaked hair flew in the wind as he took his son out for a spin on his wheelchair. His former wife’s luxury SUV was parked outside the hospital.

Over coffee, Brian gave me a photocopy of a handwritten poem he’d composed when he was still sober back in 1994. He also loaned me his copy of When Rabbit Howls, a book about a two-year-old child who created an inner world to escape the horror of violent abuse. The book clearly meant a lot to Brian.

I gave him some money and a windbreaker I had bought for him at a local store and said I’d see him again in the spring. Which never happened: Brian died alone in his small apartment at Nestor Falls less than four months later. His son told me he’d had a couple of strokes and suffered a massive brain aneurism. He was 66.

This is the poem he wrote, entitled “The Bell.”

In the child’s mind he can hear it,

the sound of the bell.

Like embers of a dying fire rekindled, memories stir,

awakened, once again to revisit the madness of a time and

place almost beyond memory.

Fleeting images, glimpses of the unimaginable.

Like a shockwave, the child remembers.

Transfixed, he simply goes away to seek solitude in

a world not of this place nor of this time.

Words echo.

“My child, my child, God has made a terrible mistake.

Come, I must recreate you into my own image.”

The child sleeps, senses on full alert.

In the dorm, others of his kind, asleep on bunk beds, row on row,

pray that tonight madness will not visit.

A slight disturbance in the midnight air—movement!

Madness is on the prowl.

Who is the chosen?

A silent scream fractures the midnight calm.

The child freezes.

For tonight madness has chosen to visit upon him

the unimaginable.

Violated in mind, body and spirit, desecrated of the sanctity of his life,

the child simply ceases to be.

The years have passed.

On a hilltop a man sits, bottle in hand.

Hair once jet black betrays strands of white.

Lined with age, the face mirrors a life gone astray.

He waits and waits, not knowing what it is he waits for.

Darkness approaches.

Tortured by memories which haunt his mind, he tilts bottle to lips,

if only to seek solace in the stupor of cheap wine.

For the man there is nothing but the emptiness and the cheap,

meaningless, high of wine-induced euphoria.

Heaven!

He succumbs to the drunken sleep

to escape the hell of a tortured mind.

It is autumn.

The season of spectral colors, with brush in hand, paints

a beautiful portrait of scenic wonders across the landscape.

Myriads of different shades and hues clothe majestic trees

in their finest attire.

The wind plays upon a flute a beautiful and haunting melody.

Mesmerizing, the beautiful music entices the imagination

to alight on wings of melody.

To journey to distant lands and times

that never were.

The child cries.