Art and Culture

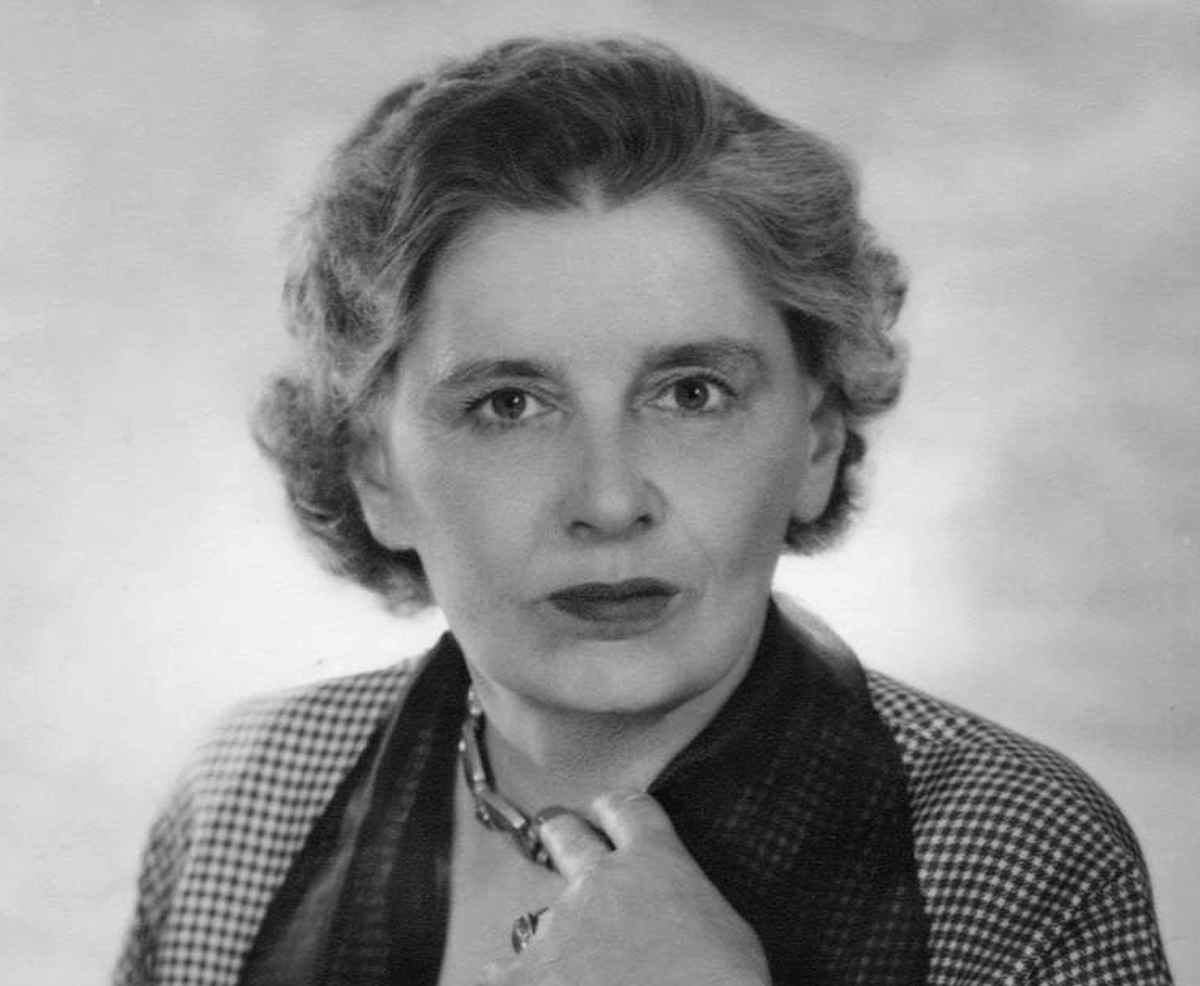

The Unsafe Feminist: Rebecca West and the ‘Bitter Rapture’ of Truth

Infantilism goes along with illiberalism, because while a liberal society requires a baseline of human freedom and responsibility.

In an era when indulgent university administrators and professors treat students like spoiled children, one longs for intellectuals who address their audience as adults. The British novelist, biographer, literary critic, travel writer and political commentator Rebecca West (1892-1983) is the tonic we need. Like other great authors of the 20th century—including George Orwell and Doris Lessing—West never received a university education. That may help explain her intellectual non-conformism and free-wheeling spirit.

West brushed against orthodoxy like barbed wire against chiffon. She was a suffragist who rejected pacifism in the First World War (and the Second); a leftist who fought communism; an internationalist who spoke up for small nations; an individualist who valued authority and tradition. West never crouched in one position. She was unflinchingly realistic. Human conflict, she said, is inescapable. It is as much a feature of art as it is of states. Eros, too, creates antagonism, for sex is dangerous. Yet human co-operation is ubiquitous. Women and men need each other, and can and do love each other. A feminism that treats women as if they were vulnerable children, and that blames a man for a woman’s own irresponsibility, was seen by West as absurd. Needless to say, her attitude to life is as far from the nursery-school feminism of today’s university—smothering, alarmist, bureaucratic—as it is possible to be.

Freedom carries obligations, West believed—the first of which is to grow up. “I believe in liberty,” she declared in a 1952 credo, particularly the liberty of a person to “be able to say and do what he wishes and what is within his power.” Because every individual is unique, each person “must know some things which are known to nobody else.” The transmission of such knowledge, which “could not be learned from any other source,” requires a space in which people are able to speak their minds.

The contrast between a state of innocence and a mature comprehension of life’s intractable demands (the “hard task of being adult,” as she put it in her 1931 book Ending in Earnest) is central to Rebecca West’s philosophy. We do not expect children to be active in politics; we protect children from politics. Nor do we consider adults who behave like children to be competent human agents. Maturity is the sine qua non of liberty because a pluralist society, unlike an authoritarian one, requires actors of independent mind who can draw a distinction between their civic responsibilities and private sentiments, who are sufficiently restrained to care for the world even as they pursue their own pleasures, and who are willing to take on onerous public burdens. Like great art, the liberal pursuit of freedom demands intelligence and discernment—a readiness “to test the veracity” of fantasies that all of us harbor to some degree and to evaluate “their importance in the light of the intellect.”

Maturity is evidenced, in short, where individuals embrace the “bitter rapture which attends the discovery of any truth,” and where they would rather be disconsolate in “communion with reality” than comforted by orthodoxy. West’s thesis is reminiscent of German social scientist Max Weber’s belief that a politics of responsibility requires “realistic passion.” What marks a mature person (ein reifer Mensch), Weber wrote in Politics as a Vocation (1919), is an attitude of principled realism enabling one to bear the perversity of the world without succumbing to cynicism.

The threat of regression to a childlike state was a recurring topic in West’s work. We see its first appearance in her 1918 novel, The Return of the Soldier , which centered on a shell-shocked infantryman’s retreat into bygone comforts, at the expense of those around him. Infantilism is a more apt term than “immaturity” here, because it implies not just a lack of emotional development, but a stubborn longing to remain childlike or return to a childlike state. While immaturity is merely pathetic, infantilism is twisted. During West’s lifetime, it encompassed several distinct forms.

The first was a male mode of dependency brought about by economic ruin. Mass unemployment during the Depression years pushed many families to the edge of destitution, but some were fortunate to contain women—wives and mothers—whose talents equipped them to work in industries less affected by the general collapse (a situation that some may recognize in today’s economy). Reason alone would suggest that men fortunate to live with provident women would have cause to be happy. But many such men were not happy at all: “Some fell into infantilism and wanted to remain in a permanent state of dependence.” Others “formed a deep feeling of resentment against their wives, which was sometimes so intense that it led to divorce.” Where a man loses his sense of virility, he will either renounce it forever and regress to the state of a child; or he will affirm virility in a twisted form, and insist that men are harmed when their superiority over women is impaired.

If the first form of infantilism postulated by West is reactive, being occasioned by economic breakdown, the second form is purposive—a deliberate, antinomian and transgressive assault on moral decency. The phenomenon was epitomized by novelist André Gide, author of such works as Isabelle, The Immoralist and The Counterfeiters. Gide’s contempt for women, deemed the cause of much of men’s wretchedness (and his interest in violent children) reflects the displacement of an infantile neurosis by which pleasure and joy are conceived as objects of guilt: If women bring pleasure, they must be hateful. West construes this unspoken connection as the root of Gide’s homosexuality

Gide’s infantilism reveals itself in a morbid attraction to cruelty—l’acte gratuit—as in Les Caves du Vatican, in which the hero brutalizes an old man on a train for no real reason. Dostoevsky also dwelled on such depravity. But whereas the Russian moralist saw it as a troubling form of modern behavior, Gide luxuriated in its nihilism. Such glee, West says, reflects “the child’s sense that in making this discovery it is breaking a command laid on it by an adult world.” This was but a component of Gide’s larger cachet in literary circles, which was based on his expression of a deep-seated desire “to stay infantile instead of becoming an adult.”

By West’s analysis, this is not only perverse; it is also sinister. For l’acte gatuit over which Gide “licks his lips” is “the very converse of goodness, which must be stable, since it is a response to the fundamental needs of mankind, which themselves are stable.”

As an act of rebellion against the adult world, l’acte gratuit has one evident limit: The gratification of such impulses must be haphazard, because each individual will find cruelty enjoyable in his own way. For rebellion to become a collective act, it must be animated by something more than idiosyncratic forms of lashing out. It needs an ideology, and a cohesive justification for rebellion. Among Western intellectuals, communism provided that cohesive justification. West’s theory about communism’s allure to the Western literati is too large a topic to be examined here in detail. But she traced one element of communism to the dissatisfaction felt by children toward their parents.

West found a useful case study in Britain, where communism took root within the socialist gradualism associated with Sidney and Beatrice Webb, the Fabian Society they championed, the London School of Economics (Fabianism’s intellectual nerve center), and the debunking satire of (among others) H.G. Wells and George Bernard Shaw. This group aimed at social improvement and the betterment of the working class. Its message appealed to civil servants, teachers, doctors and lawyers who sought to reform local government along democratic socialist lines, upgrade working standards, improve housing, education and the prison system, and, in tandem with the trade-union movement, provide British workers with a decent standard of living.

West’s appraisal of the Fabian movement is double edged. Fabian policies often struck her as sensible, humane, overdue and, especially in regard to local government and penal policy, effective. (The National Health Service, established in 1948, is due in no small part to earlier Fabian efforts.) But as Fabianism evolved, its authoritarian and bureaucratic overtones became more evident. The Webbs, in particular, were early enthusiasts of Bolshevism. The circle they assembled around them, being well off and well known, produced a sort of aristocratic socialism that was corrosive of all authority besides its own.

Fabian children received an education in contempt. As West observed in a 1945 article for Time and Tide: “The foundation of their [Fabian parents’] creed was the assumption that there was nothing in the existing structure of society which did not deserve to be razed to the ground, and that all would be well if it were replaced by something as different as possible. They were to do it quietly, of course; but the replacement was to be absolute. To them the past was of value only in so far as it gave indications of how to annul the present and create a future which had no relation to it.”

In volumes lying around the houses of the privileged socialist set, “the values of our [British] traditional culture made their last stand and bled and died, all except altruism and truthfulness and austerity” (on which Bernard Shaw and his close associates claimed a monopoly). The idea of loyalty to the Crown or of fighting for one’s country was laughable to these aristocratic intellectuals because Britain was, after all, a ridiculous country when it was not simply malignant. West would be appalled, but not particularly surprised, at the current predilection among intellectuals to expand this antipathy to Western civilization in general.

Afforded ample material comfort and an expensive education, West noted, the offspring of these celebrity socialists rebelled in a curiously conformist way. They had been taught to be dissenters, and so they would remain. They had been taught to enjoy being in opposition as distinct from being in power; and “nothing is easier than being in opposition,” West wrote in The New Meaning of Treason (1964). But as the welfare-state vision of their parents became a reality, the fantasy of opposition became more difficult to sustain. The election of the Labour Party to government in the British general election of 1945 meant that reformist socialists now had the means to put forward a socialist program of mass industrial nationalization. If rebellion was to continue, it must find a new vehicle where “the glorious drunkenness of permanent opposition” could continue.

The children found this intoxication in communism—which West described as “a haven to the infantilist,” because it exists both in and outside of government simultaneously: the Soviet Union was a state that opposed the state in which the younger generation lived. Communism enabled a loyal disloyalty, a rejection of one’s own country while affirming obedience to another that is far more radical. The make-believe to which communists subscribed was that the Soviet Union portended a world of peace, plenty and justice, even as its leaders liquidated millions and revealed themselves willing to form a pact of convenience with Nazi Germany.

Moreover, the communism club was not without its privileges; and this was an important factor for a group fearful of becoming déclassé and unable to repeat the material success of its parents. Soviet communism bestowed esteem on visiting scientists; it feted foreign tourists and commentators; and it showered honors on those who spied for the proletariat. In short, communist intellectuals were men and women resolved to trump their parents’ radicalism where it had become all too conventional, while also creating a new self-serving moral hierarchy soldered to a collective cause.

* * *

The ex-Communist Whittaker Chambers quipped that Rebecca West was “a socialist by habit of mind, and a conservative by cell structure.” He forgot to mention her feminism and her liberalism. In any event, political admixtures are common in many fine minds. Was Alexis de Tocqueville a conservative or a liberal? He was both and more besides, depending on the matter at hand. Alexander Pope, confirming his own political latitude, joked: “Tories call me Whig, and Whigs a Tory.” And Pope’s friend and confidant Jonathan Swift was equally hard to peg, prompting George Orwell, in Politics vs. Literature (1946), to dub him a “Tory anarchist, despising authority while disbelieving in liberty, and preserving the aristocratic outlook while seeing clearly that the existing aristocracy is degenerate and contemptible.”

A writer who draws on multiple traditions can never sink into the dogmas of any one of them. Or indulge their extremes. But while West’s politics were multiform, her liberalism stands out, today, as her most admirable quality. This is not just because those committed to free expression must keep speaking to and against those who would hear only one voice, and because today’s most popular forms of feminist expression promote censorship and victimhood. West’s liberalism also feels morally urgent because liberals are engaged in an ongoing fight with themselves. In that fight, the priority should not be compassion or conciliation but truthfulness. As West observed, “it is never possible to serve the interests of liberalism by believing that which is false to be true…The fact-finding powers of liberals have, therefore, always to be at work.”

Infantilism goes along with illiberalism, because while a liberal society requires a baseline of human freedom and responsibility, the infantilized citizen is dependent on a person, group, or identity. One need look no further than our colleges and grievance-saturated social media to see how this works. The basic cause of such malaise may lie more in ideology than psychology, but the psychological consequences are plain enough.

Rebecca West remarked that Freud “gave sadists a new weapon by enabling them to disguise themselves as children.” Social media adds masochism to the mix, as when some reckless accusation tempts the unfortunate target to engage in self-abasement. Yet the accused have responsibilities, too, and unthinking contrition is its own kind of infantilism. Those unwilling to defend their opinions, and who self-flagellate in public on the basis of non-existent crimes, invite their tormentors to apply an extra dose of humiliation. The invitation is rarely declined.

If we have no right to be comforted as adults, we can still take comfort in exemplars of independence and individuality. Rebecca West is not as well-known as many other great writers of the 20th Century. But perhaps that will change in an era when infantilism and ideology are renewing their assault on that “bitter rapture” called truth.