Top Stories

If That's What It Means to Be a Writer, I Quit

Kauffman defended himself from charges of homophobia by saying that he wasn’t against the ‘gay influence’ in theatre, only its insidiousness.

Back in 2009, I wrote an article for Canada’s Globe and Mail titled If that’s what it means to be gay, I quit. “If you speak to the leaders of most gay and lesbian political groups about what it means to be gay today, they will probably answer using the words ‘love’ or ‘family’ or ‘caring,'” I wrote. “Well, the world of pretty rainbows, church on Sunday, monogamy, respectability and good citizenship is not the world I signed onto when I filled out my gay card.”

I have been an out gay writer and activist in Toronto for nearly 40 years. For some time, I have complained about gay assimilationism—our cultural identity switch from gay sexual revolutionaries to obedient corporate citizens. Perhaps that’s because I come from another time.

I remember the day I figured out I was a homosexual. I was at my grandmother’s house and I picked up a copy of Life magazine (June 26, 1964: Volume 26, #6). I was 12 years old. It was an article called Homosexuality in America, by Paul Welch. The photos were hypnotizing: brooding young men in leather jackets drinking in seedy looking bars and smoking under streetlights in tantalizing groups. Somehow, I just knew I belonged to this illicit world. I was one of them.

Though I knew I was gay in the 60s, I lied to myself and everyone else about my true identity. So art became the locus of my rebellion. I was drawn to 20th century plays that challenged the bourgeoisie. I became obsessed with Tennessee Williams, William Inge and Edward Albee. In 1966, Stanley Kauffman (then a critic for The New York Times) attacked these playwrights for their insidious gay influence. In Homosexual Drama and its Disguises Kauffman spoke of how three dramatists (whom he did not name) presented a “badly distorted picture of American women marriage and society in general.” (Before his death, Edward Albee suggested that everyone at the time knew who Kauffman was talking about.) “A recent Broadway production raises again the subject of the homosexual dramatist,” wrote Kauffman. “It is a subject that nobody is comfortable about. All of us admirably ‘normal’ people are a bit irritated by it and wish it could disappear. However, it promises to be a matter of continuing, perhaps increasing, significance.”

Kauffman defended himself from charges of homophobia by saying that he wasn’t against the ‘gay influence’ in theatre, only its insidiousness. In other words, he wanted gay writers to come out of the closet and write openly about their lives. I didn’t read Kauffman’s article as a teenager, and I didn’t think of Williams, Inge and Albee as homosexual writers, but I knew that somehow, in their opposition to the status quo, they spoke for me.

In 1972, I was pondering a career as a cellist and composer. But when I was accepted into the acting program at York University, in the suburbs of Toronto, I was ineluctably drawn to theatre. Theatre attracts gay men because the theatre is a closet. If you are the least bit effeminate (as I am)—and you are male—then your mannerisms put you on stage. People were always watching me and asking me, “Why do you talk so much with your hands?” I could now say, “Well, I’m an actor and flamboyant!’

Also, theatre is a disguise; it’s about hiding. (Despite the best efforts of Konstantin Stanislavski and David Mamet, no one has ever made actors stop acting and just “be themselves.”) Also, theatre is an escape. I knew that I was gay inside. But even if I never kissed a man, it still seemed to me there was a happy “healthy” world out there that I would never be a part of—the world of what Kauffman had called “admirably ‘normal’ people.”

Like Blanche Dubois, I would end up mad and lonely, probably. So, as much as I was drawn to the rebelliousness of gay playwrights who “wrote straight,” I also was drawn to musical comedy because it offered an escape. To this day, you will find that schools that prepare young performers for musicals—i.e., “Triple threat” schools—are filled with young, gay, effeminate actors.

Straight playwrights such as Henrik Ibsen and Eugene O’Neill had laid the foundation by critiquing middle class culture. Gay playwrights—Tennessee Williams, Edward Albee, Joe Orton, Jean Genet—continued the tradition, with their anti-heterosexual agenda hidden inside a critique of middle class life. But their gayness revealed itself in subtle ways. All were stylists of the highest order, and made a fetish of language. Their work is either poetic, or witty, or both. It’s as if all their anger, flamboyance and femininity is compressed into wordplay. In addition, the subject matter is hyper-sexual, violent, and obsessed with the spirit of Épater la bourgeoisie. In the 19th century, Ibsen’s Ghosts was scorned by critics as “an open sewer, a loathsome sore unbandaged.” And as recently as 2006, Carol Rocamora described Tennessee Williams’ plays, in The Guardian, as “desperate dramas of alcoholism, addiction, incest, madness, sexual voracity and violence.”

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, I was content to imagine myself an actor (and budding playwright), and hide myself at theatre school reading the gay playwrights I idolized, while humming Broadway tunes. But in 1969, the New York City police infamously raided the mafia-run Stonewall bar. Sex trade workers, drag queens, lesbians and gay men decided to fight back. Overnight, society’s secretive liars became dangerous, sexual, truth-telling, boundary-flaunting iconoclasts. During the 1970s, gay men and lesbians kept 1960s sexual liberation alive. Articles in Toronto’s gay magazine, The Body Politic, affirmed that the gay “lifestyle” offered viable, healthy, humane alternatives to monogamy. Gay men—as Jean Genet noted—were part of the global oppressed, and also part of the revolution. Queers endorsed open relationships, promiscuity, and S/M as politically radical and psychology healthy—not only for gay men—but for everyone.

This was the gay world I finally entered in 1979—the year I left theatre school and started Buddies in Bad Times theatre in Toronto. At first, I didn’t write “gay plays.” But in 1981, I wrote a play about gay American poet Frank O’Hara. I immediately lost my friendships with the two men who co-founded Buddies in Bad Times. One of them, Jerry Ciccoritti (now a successful television director), dismissed my work, saying “Sky just likes shocking mommy and daddy.” He was right. After coming out, I dedicated my life to writing like an openly gay version of my favourite 1960s icons.

When AIDS appeared in the early 1980s, it was terrifying and traumatic for everyone. To me, it also seemed very unfair—because just after coming out of the closet I was being told to “wrap it up.” But AIDS inflicted more than just a death toll on the gay community; it attacked the very core of the gay psyche. Imagine, if you will, not only contracting a fatal illness, but being told you are the incarnation of evil. Imagine your family abandoning you. Most gay men will say that AIDS was a “lesson,” and that gay men, as a result of the AIDS epidemic, became more monogamous and loving. This is simply not true. Many gay men were monogamous and loving before AIDS (and those two things don’t necessarily go together in any case). It is certainly true that, with the advent of AIDS, a unified community of gay men educated themselves very quickly about safe sex. But gay men were not just afraid of the illness, they were afraid of of being demonized. So they learned how to present themselves as respectable citizens, not only by practicing safe sex, but by pretending to act like straights.

AIDS taught gay men how to lie again. Most gay men, that is. Not me. AIDS just made me more sexually outspoken. In 1985, I wrote a play called Drag Queens On Trial about Lana Lust—who defies AIDS with her uncompromising libido and high heels. When John Glines, the producer of Harvey Fierstein’s Torch Song Trilogy read my play, he told me he wanted to produce it in New York. I was ecstatic. But it all blew up in one conversation. “Oh, it’s funny, hilarious, really great—keep the jokes—and I’ve got three great drag queens to play it,” he told me. “The only thing is, you’ll have to take the AIDS stuff out.” I said, “What? Take out AIDS?” That was the whole theme.

“No, it’s gotta go. Sorry—too depressing! Gay men don’t want to see something about AIDS. It’s too close to us. Not now.”

This was the turning point for me. I began to understand how different my views were from the views of my own community. Some of my gay friends were rejecting gay liberation and embracing assimilation. I remembered that the straight newspapers all loved Drag Queens on Trial, but the gay rags were conflicted about it. In fact, my drag queens weren’t allowed into many gay bars to promote the show. The owners were so obsessed with the assimilationist “clone look” in the late 80s (a masculine look that was in vogue) that they had banned drag queens. I became so estranged that in 1997, I left the theatre I’d co-founded.

* * *

If you were to ask most gay men what part their sexuality plays in their lives today, they would probably say “none.” Gays and lesbians today say their sexuality is only related to a genital preference—something many consider inconsequential. They aspire to the same values as middle class heterosexuals, which means they wish to get married, have children, buy things and support their local police. The only problem with this is that the monogamous heterosexual model, which most gays and lesbians now ape faithfully, isn’t very practical.

Compulsive heterosexuality is founded on the lie that most people are naturally suited for monogamous marriage. This lie can be maintained only when it is accompanied by a whole range of practices that—at least until very recently—heterosexuals didn’t want to talk about: sexism, prostitution, strip clubs, rape, and the molestation of children. The truth is that gay men have not become less promiscuous, they have just learned to lie like straights. The gay bars (although there are fewer of them) are still busy with horny gay men, as are bath houses, parks, toilets, crack/meth sex parties—and the ubiquitous online “hookups.” Modern straight and gay hypocrisies are wonderfully facilitated by modern technology. We hook up on cellphones, and do not have to actually appear in public to get laid. This is a godsend for straight men who want to cheat on their wives, or gay men who are still in the closet—and/ or who want to appear non-promiscuous, or monogamous. Hence the popularity of Grindr.

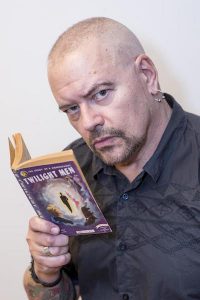

As a writer, I have continued to write novels plays and books that are mainly focused on gay life, love and sex. My books are not popular with gay men. The people who read them are, well, people who read (a limited audience these days). My work now lives permanently outside the mainstream.

The increasing marginalization of queer work—or any sexual work at all, really—is related to two political movements: trans politics, and #MeToo. Don’t get me wrong: Both movements have positive value. As a gender non-conforming gay male and drag queen, I have devoted much of my life and work to challenging gender. And I appreciate trans theory, and the efforts it makes to change the gender status quo. And as an ardent male feminist, I am happy to see women call out male abusers. But the politics of trans theory and #MeToo can be significantly anti-sexual, in direct opposition to pre-AIDS political movements—women’s liberation, sexual liberation and gay liberation. #MeToo is considered by some critics—particularly French feminists such as Catherine Deneuve— to be an anti-sexual. Many trans theorists state over and over again that being trans has everything to do with gender and nothing to do with sex.

What is most frightening about the #MeToo movement in terms of aesthetics is that it demands the rigorous analytics of social justice be applied to creative work. Michele Perrot, speaking of the public letter signed by Deneuve and other prominent French women in opposition to the excesses of #MeToo (“Nous défendons une liberté d’importuner, indispensable à la liberté sexuelle”), notes that the authors “fear that the #MeToo movement dents creative, artistic and sexual freedom, that a moralist backlash comes and destroys what libertarian thinking has fought hard to obtain.” Has this actually happened? Absolutely. A female Canadian filmmaker I know told me recently of her difficulties in acquiring permission from the actors’ union to make a film involving—as she described it—”a plus-sized woman having rough sex with a man, in which they would hit and bite each other.” The union denied permission, saying effectively that that the scene was “too much” in the #MeToo era.

I have written drag-queen roles for myself, and am certainly a fan of the sly and radical rebelliousness of camp humour. At the Q2Q Conference in Vancouver in 2016 (“A Symposium on Queer Theatre and Performance“), several transgender artists raised objections to drag-queen performers on the basis that they were “cruel.” I was asked to read some very campy poetry at a high school recently—and also lectured on drag (though I wasn’t in drag). One of the teachers told me that the whole idea of having a drag queen at the school had only recently become controversial—not because it offended conservatives, but because some educators though it might be offensive to trans people. The reason some trans theorists object to drag is because they think that drag serves to mock or satirize trans people.

* * *

Before the modern scientific age, people who wanted to understand the world didn’t look though a microscope. They read a prayer; or a poem, which could be considered equivalent to the word of God. Then the puritans arrived. Their messenger was Petrus Ramus, a 16th-century philosopher (and Protestant convert) who railed against over-decorated, complex, metaphorical language—which is to say, poetry. He championed the so-called “plain style,” which became popular with many puritans.

The Royal Society, founded in 1660, is known for its dedication to the scientific method. But it also policed speech, which is one of the reasons Shakespeare remained surprisingly unpopular until the bardolator David Garrick began to stage his plays (and star in them) in the mid 1700s. Thanks to the puritans, poets and critics became suspicious of what were called “quibbles”—a 17th-century word for a pun. Wordplay was distrusted because it endowed language with double (or sometimes triple, or quadruple) meanings. For purveyors of plain speech, it was important to know the exact moral message of whatever was being said or written. It was required that the message be clear, and related to facts (or approved faith), not the imagination.

David Garrick, in his elaborate adaptations of Shakespeare, managed to both clear the work of quibbles (Garrick’s adaptations were, effectively, punless) and provide new endings to plays such Romeo and Juliet and Macbeth. In these moralistic finales, evildoers cried to God for mercy as they were sent to hell, and the good flew off to heaven. Shakespeare’s actual plays—by contrast—are essentially amoral. For all great art is amoral.

As a rhetorician, Shakespeare was more interested in presenting eloquent and uniquely persuasive arguments on both sides of any issue, than in celebrating the good and punishing the evil. In fact Shakespeare’s work presents the most passionate arguments in favour of evil you will ever find in serious literature. Samuel Taylor Coleridge called Iago, famously, “the motive-hunting of motiveless malignity.”

Like Shakespeare, Tennessee Williams was a master rhetorician and poet. Streetcar Named Desire centres around the fundamental Manichaean argument between the body (Stanley) and the soul (Blanche). Williams’ brilliance lies in the fact that these opponents are evenly matched. Stanley is sexy, funny, and honest—but Blanche is brimful of poetry and pathos. One gets the feeling that Williams had as much sympathy for Blanche’s point of view as for Stanley’s. On leaving the theatre, we are torn. What is the answer? There is none; only an eternal, dangerous question. Williams, Albee, Orton and Genet raised dangerous questions and didn’t answer them. This is why they challenged the status quo and audiences, and why their work still stands as art. Art leaves us torn and uncomfortable. Mere entertainment confirms us in our comfort zone.

Garrick’s adaptations of Shakespeare were entertainment, like today’s hit musical Come From Away—the longest-running Canadian musical in Broadway history. Come From Away is the story of the people of Gander — a small Newfoundland town whose residents took stranded travellers into their homes when their planes were grounded in the days after 9/11 . This relentlessly cheery musical congratulates its middle class white audience on being white and middle class: “Yes, you are good kind humans! You took people of all colours, sexualities and creeds into your homes! You went and bought toilet paper for them! It was very inconvenient! Congratulations!” But most importantly, Come From Away has a positive, Christian, feel-good message audiences can take away, without equivocation: Do unto others as you would have them do to you.

Consider, in contrast, contemporary attitudes to works by Woody Allen and Louie C.K.. It is no accident that these two artists and poets are comedians. Stand-up comedy can be very dangerous; much of what any comic does has to do with making language and meaning untrustworthy through irony, sarcasm, and puns (quibbles). These two men are great modern poets of the cinema (Allen) and television (Louie C.K.). #MeToo works doggedly to rip Annie Hall and Manhattan from the canon, citing Allen’s personal crimes and misdemeanours. But I predict that ultimately they will not succeed—because these works of art ask big questions, but don’t answer them, which is what makes art art.

Louie C.K.’s comedy series Louie—and his drama Horace and Pete—are Chekhovian in their manner, their danger and their eloquence. Have you seen Louie C.K.’s movie I Love You Daddy? You probably never will, because Louie C.K. has been cast into reputational purdah due to his personal life. He may not be as great an artist as Shakespeare, but he does share one thing with the bard: His work will slowly slip from view, at least for a time, due to it’s amorality in an excessively puritanical time.

Catherine Deneuve and her fellow French Feminists criticize the “confusion of the man and the work,” in reference to Roman Polanski. I am not defending the private lives of Woody Allen, Louie C.K., Roman Polanski—or any other poet (or honorary poet) who has led an immoral life or held immoral personal views. It’s important to note that Ezra Pound and Knut Hamsun were Nazi sympathizers. Picasso was apparently quite abusive to women. Dorothy Parker was an incorrigible drunk, and William Burroughs was a heroin addict. The list goes on and on. In fact, sadly, it may be somewhat of a prerequisite, for any artist, to not lead an exemplary personal life, or to hold personal views that are outside the realm of “admirably ‘normal’ people.” I am not defending the personal lives or the views of these artists, but their art. This is because artists’ personal lives are now being used as an excuse to ban their work at a cultural moment when we risk slipping back into an earlier, puritanical era.

* * *

From the 1700s and on into the late 19th century—around the time when Oscar Wilde wrote The Importance of Being Earnest and The Decay of Lying—Western poets, novelists and playwrights were taught that their work must be sentimental, kind, Christian and well-intentioned. All this was blasted apart by the modernist styles of realism, naturalism, and eventually by the anarchy of modern visual art. But for as long as this puritan influence on the arts endured, it resulted, I would argue, in some very bad poetry, novels and plays.

We seem to be going through another era in which poets are to be silenced in the name of morality. Let’s just hope it doesn’t last quite as long as its precursor. My job as a poet is not to improve you morally, or to present a clear, kind, socially approved message.

In fact, if that’s what it means to be a writer: I quit.