Canada

An Academic Mobbing at McGill

In true mobbing fashion, the extreme and racist allegations that Ibrahim was a typical Arabic misogynist and sexual predator simply do not add up. In fact the opposite is true.

Editor’s note: More than 200 pages of supporting documents have been gathered by Professor Ibrahim for use in a defamation lawsuit he is engaged in against a student and a colleague. These documents include both the Minority and Majority Reports issued by the Departmental Tenure Committee, student testimonials and affidavits, as well as a variety of departmental communications involving Professor Ibrahim’s tenure. These materials are not publicly available but have been reviewed by the editors and they are referenced and quoted throughout the article.

On February 6, 2018, a faculty member of McGill University’s Institute of Islamic Studies (IIS) emailed Robert Wisnovsky, the newly installed director of the institute, to report that he had overheard three women talking in an elevator about their desire to take down tenure-track faculty member and Islamic Law Specialist Ahmed Fekry Ibrahim. “I want him to get fired,” one student wearing a hijab said. “He is the most Islamophobic prof I have ever had. I fucking hate him.”

It’s unclear whether the comments were uttered randomly, or if, as seems more likely, the young woman was knowingly contributing to a defamation campaign aimed at destroying Ibrahim’s career. Baseless allegations implicating Ibrahim as a misogynist and sexual predator had been spreading through the department for many months—some including racist innuendo about his “Arab sexuality.” One student alleged in a statement to the ISS that Ibrahim had sent her flirtatious texts and emails until she asked him to desist and that, since then, she felt “frightened” and “intimidated” when she encountered him on campus and he “made sure to make eye contact, and even say hello.”

Like most targets of such ruthless smear campaigns, Ibrahim was slow to understand that he was the victim of a workplace “academic mobbing.” Swedish psychologist Heinz Leymann first articulated the syndrome of mobbing in the early 1980s as “an impassioned, collective campaign by co-workers to exclude, punish and humiliate a targeted worker.” The urge “travels through the workplace like a virus.”

Kenneth Westhues, professor emeritus at the University of Waterloo, himself a victim of such a campaign, devoted himself to the topic for decades. In his 2006 book, The Envy of Excellence: Administrative Mobbing of High-Achieving Professors, Westhues developed a list of criteria to identify true mobbing. Amongst them:

- The target is popular and high-achieving. Mediocre performers tend not to arouse the eliminative impulse in peers.

- Unanimity prevails among colleagues: “The loss of diverse opinion is a compelling indication that eliminative fury has been unleashed.”

- The charges are vague and fuzzy.

- Rumours and gossip circulate about the target’s misdeeds: “Did you hear what she did last week?”

- Unusual timing of the decision to punish, e. g., apart from the annual performance review.

- The adding up of the target’s real or imagined venial sins to make a mortal sin that cries for action.

- A lack of due process.

- The rhetoric is overblown. “The more fervent, excited and overwrought the language used against the target, the less likely is the basis for exclusion of anything but a collective will to destroy.”

- The target is seen as personally abhorrent, with no redeeming qualities; stigmatizing, exclusionary labels are applied.

In a classic mobbing episode, the propelling “sin” is either venial or non-existent, but is often predicated on an easily demonized aura of nonconformism. The accused at first assumes his friends and colleagues will rush to defend him, but as defenses are mounted, the severity of the allegations will increase, making it clear that to even defend the target’s rights is tantamount to endorsement of abhorrent behavior. Even those closest to the target may turn on him or her in order to show allegiance to the cause, and to distance themselves from the growing threat of danger that will not only take down the target but destroy those with the courage to stand against the mob.

Director Robert Wisnovsky had a major problem on his hands. In the age of #MeToo and University Culture Wars raging over identity politics, public call outs, and no-platforming, could Wisnovsky, a white “privileged” scholar with degrees from Yale and Princeton, effectively negotiate a solution to a growing cabal of radical students who were successfully painting a Muslim scholar as an Islamophobe and sexual predator? Wisnovsky wrote back to the faculty member who reported the incident in the elevator to say that he was aware of the problem and trying to resolve it.

In May of 2018 with Wisnovsky as Chair of the Departmental Tenure Committee (DTC), Ibrahim became the first tenure-track scholar he could find on record in the 66-year history of the IIS to be denied tenure. His academic career had been destroyed. Yet, like all academic mobbings, the justifications for the destruction of a career do not hold up outside of the manufactured hysteria. To any reasonable unbiased outsider, questions remain.

* * *

Ahmed Fekry Ibrahim was born and raised in a working-class neighborhood of Cairo, where at an early age his Sufi Muslim parents enrolled him in a conservative school, starting him on his trajectory to expertise in Islamic Studies. Ibrahim thrived in this environment, rising to the top of his class in elementary and high school, and then later becoming the top student in his B.A. Azhar University cohort. After a stint as a journalist—he became the Cairo correspondent for the Middle East Times and later a reporter for an Arabic-language newspaper—Ibrahim did his doctoral studies in the U.S., after which, in 2012, he was hired as a tenure-track specialist in Islamic Law at McGill’s IIS.

As the first person in his family to receive a BA (let alone a PhD and a number of prestigious appointments), his successes were a source of enormous pride to his parents. Indeed, for many in his extended family’s home village, Ibrahim was an inspiration, even a type of hero, albeit soon to become a tragic one.

In the spring of 2014, Ibrahim (then in his mid-thirties) became romantically involved with one of his former students, 20-year old MG. McGill did not have a policy regarding professor-student relations, and Ibrahim was aware that it didn’t. MG was no longer Ibrahim’s student; therefore, the relationship was, he felt, his private business. Nevertheless, the relationship could not have been a secret in the relatively small, fishbowl atmosphere of the IIS.

Early in their relationship, Ibrahim hired MG as a Research Assistant. Since MG was paid the same wage as other RAs, and did the work competently, he was for a time able to rationalize the conflict of interest. But discomfort persisted and by mutual accord the assistantship ended in September. The relationship continued until April 2015, when Ibrahim broke it off.

After the breakup, which MG seemed to accept but, according to Ibrahim, with covert expressions of resistance (texts, emails emanating ambiguity as to their relationship status), she began to regard herself as a victim of a power imbalance. She shared her sense of injury with two feminist IIS professors, with whom she was on friendly terms. They took up her grievance with alacrity.

In early June 2015, withholding the subject matter, then IIS director Rula Abisaab asked for a conference Skype meeting with Ibrahim, which materialized on June 9. Four members of the IIS told Ibrahim his relationship with MG had created a “toxic environment” at the Institute. This came as a shock to Ibrahim, but he took it at face value, and made an individual apology tour of the department. Only two people declined to meet with him, both of whom would later be identified in student testimonials as vocal detractors.

Rumours flew within the McGill community and then in September, an anonymously authored article appeared in the McGill Daily, entitled “Let’s Talk about Teacher.” The particulars make it clear the writer is MG, describing her relationship with Ibrahim. The article portrays Ibrahim as a serial abuser of women who is willing to use his authority for sexual gain. Ibrahim categorically rejects MG’s characterization of the relationship, and asserts the article is replete with falsehoods. MG, he told me, was a confident and intelligent woman with full agency who had, in fact, initiated the relationship.

Because it was the spark that ignited a forest fire, I spoke to Ibrahim at some length about his relationship with MG. Did he not see that the optics were sketchy? In fact, he didn’t. He told me that if McGill had had a policy proscribing professor-student relationships, he would have respected it. But he saw nothing morally wrong in it. In Egypt, he said, marriages with former students, even with a 10 or 15-year age disparity, are not frowned upon. He confessed that up until this happened to him, he had been “ignorant of that feminist discourse,” meaning the preoccupation with power imbalances. With time to reflect, Ibrahim has realized that becoming involved with any student was an ill-judged decision.

Not only had there been no policy forbidding student-professor relationships at the time Ibrahim became romantically involved with MG, there was still no policy in place against them when he was denied tenure. (As I write, in what might be called a “barn-door” flurry of responsible stewardship, McGill is now in the process of putting such a policy into place.)

Here we need to be absolutely clear: the conflict of interest arising from his employment of MG was unethical. But the important thing to understand for this story is that, at the time, the university did not consider it a serious infraction meriting a career-ending outcome, particularly since Ibrahim was not the only member of the institute to run afoul of the same issue. There are four couples at the IIS; several have been involved in conflicts of interest of this kind, as have many other couples in other departments.

In September 2016, Ibrahim was penalized by the university—not for the conflict itself, but for failing to disclose the conflict in writing (which he learned after the fact was de rigeur), although he had apologized for it orally. The conflict was not adduced as a reason for denial of tenure. (In fact, it couldn’t be, given the strict guidelines for tenure assessment, which are constrained to three areas: scholarship, pedagogy and service to the academic and greater community.)

In retrospect, Ibrahim came to see the kerfuffle over his affair with MG, and the hyper-inflated allegations of his mobbing that arose from it, as a smokescreen for the real issue: smoldering resentment over his pedagogy—perceived as politically incorrect by a minority of students and faculty alike—in relation to the teaching of contentious issues in Islamic law. That is to say, he did not see his role as an apologist for historical ideas and processes that may have nothing to do with Islam itself as a religion. Rather, he considered himself a teacher of law comparable to some other Canadian teacher of, say, constitutional law. If certain texts were problematic—well, that was something to discuss, not suppress. He knew other professors took a different approach, but did not imagine the difference would spill over into open hostility.

* * *

Sarah Abdel Shamy (sometimes spelled as Sarah Abdelshamy) was a nineteen-year-old first-year student at IIS who was politically active in the McGill World Islamic and Middle East Studies Students Association(WIMESSA). She enrolled in Ibrahim’s ISLA 383 2017 winter course along with two female friends. From the outset, Ibrahim found her difficult. She seemed to come in strong on the first day with an agenda, rejecting his pedagogical authority every time his statements on Islam conflicted with her modern-leftist interpretations.

Ibrahim told me he tried hard not to irritate her, but she was impossible to placate. For example, when she challenged his teaching of the pre-modern notion of jihad, she insisted “Islam means peace.”(It actually means “submission.”) He told me that instead of correcting her, he gently informed her that “our idea of peace and our understanding of the foundational sources of Islam are different from Muslims living in the late antique or medieval periods.”

Ibrahim’s teaching style is modeled on the Socratic method, a strategy in common usage in law schools where argument is a foundational skill, but less common in the humanities, most likely because the method leaves discussion paths wide open, where they can easily veer into controversial terrain. His custom was to introduce a subject via a text, pose questions, allow dialogue to ferment organically, play devil’s advocate if necessary to encourage debate, and in general allow students maximum freedom to express their ideas without censure.

On January 29, 2017, two weeks into the semester, a mass shooting took place at the Islamic Cultural Centre in Quebec City. Six men were killed and nineteen others injured. The tragedy shook Canadians to the core. Two days later, Ibrahim walked into class, asked for a moment of silence, and began to lead a discussion about Islamophobia. And that was the moment when his real troubles in the department began.

Ibrahim opened the mosque massacre discussion by postulating a hypothetical scenario in which the students were confronted with an Islamophobic uncle who claimed that jihad in Islamic law promotes violence, and to consider what arguments they might use to counter this statement. A cool and rational exercise, to be sure, though perhaps not the best approach at a time of mourning and perhaps exclusionary only in that, for the purposes of intellectual inquiry, he was asking some Muslim students to pretend they had an Islamophobic uncle. But also not proof of Islamophobia—Shamy’s charge, and an accusation Ibrahim finds highly offensive.

While most of the students entered into the discussion in the positive spirit intended, Shamy and her two friends, according to student testimonies, huddled together, and created a tense atmosphere with loud critical asides to each other. After the class, one of Shamy’s friends—I will call her “Najah,” though her real name does appear in the court documents—wrote a sternly critical email to Ibrahim, to which Ibrahim immediately replied in a conciliatory spirit, offering to discuss the matter.

Two days later the follow up class went badly as well. Ibrahim attempted to hold a discussion about the negative aspects of the previous class, but instead of clearing the air and restoring harmony, Shamy ratcheted up her choleric tone and lashed out at Ibrahim, as well as at non-Muslim students in the class who agreed further discussion was a good idea. Shamy, Najah, and another friend stormed out of the class in protest.

Ibrahim appealed in writing to Wisnovsky for advice in dealing with Shamy. He explained in detail what had happened in the controversial classes and included emails from students who expressed their support for his attempts to create a teaching moment on Islamophobia. He also expressed his frustration at being asked to treat Islamic law in a “presentist and ahistorical” way.

Wisnovsky met with Shamy and then afterwards advised Ibrahim to apologize to her. This was of course not the outcome Ibrahim had hoped for, nor was it one that would solve the problem. But in a gesture of good faith, Ibrahim did meet with her, and extended an apology for his insensitivity regarding the mosque massacre. Shamy responded by telling Ibrahim that an article she had written about him would soon appear in the McGill Daily.

And so it did. In “How Much Does a Promise Cost? Turning Islamophobic Violence into Strength,” Shamy portrays herself as the avatar of victimhood: “I will never fully feel like I belong in a classroom…and it is deepened because of my religion, race and gender.” She says she enrolled in Islamic Studies because it “overlaps with my own identity,” but McGill failed to provide her with “protection” and the “safe spaces” she needed.

Shamy complained about the ratio of white students to Muslims (70:30); she complained that “it would be easy for [Ibrahim’s] information to take on a propagandic [sic] or an Islamophobic turn”; she complained that the class environment was “extremely hostile and uncomfortable”; she complained that Ibrahim privileged the opinions of white males over “visibly” Muslim women (Shamy wears a hijab and is believed to be the vocal student in the elevator); she complained that McGill had turned “a blind eye to ongoing violent behavior [sic].”

The McGill Daily article sickened her friend Najah, who saw no relationship to truth in Shamy’s words. To her immense credit she decided to speak up, knowing that this would mean the loss of her friendship with Shamy, and would most likely lead to her own shunning by ideological comrades, which in fact it did. Najah acted decisively by convening a meeting with Wisnovsky on February 20 to refute Shamy’s article. So, at this point, Wisnovsky was well aware that Shamy should not be considered a trustworthy narrator with respect to Ibrahim’s pedagogy.

On April 28, 2017, the ISS and Associate Provost Angela Campbell held an open meeting to discuss issues related to sexual violence on campus. Despite the fact the meeting’s agenda was meant to focus on the formation of policy, a student affidavit reports that Shamy launched into a “rant” about Ibrahim in which she called him a “rapist” and accused McGill of protecting him. Other students then denounced him with similarly overblown rhetoric. (Shamy did not respond to my repeated requests for an interview.)

Ibrahim’s colleague, Pasha Khan, is alleged to have alluded to Ibrahim as a “rapist” after repeated warnings to a student to avoid this “predator.” That student, who would go on to work with Ibrahim as a TA, testified in an affidavit that she soon realized Khan’s accusations were untrue, and subsequently asked Ibrahim to be her thesis supervisor.

Shortly after this, in May 2017, Ibrahim was approached, informally and off the record, by a delegate of the Provost, inviting him to consider taking part in “discussions” that might be in his interest. The pith of the discussions, according to Ibrahim, was the offer of a quiet payout if he would drop his tenure application and resign from McGill.

Ibrahim refused Provost Manfredi’s offer without a moment’s hesitation. Since he had done nothing to jeopardize his tenure or his good name, he reasoned, why should he act as though he had? It is now small consolation to him that his indignant refusal of this pusillanimous proposition speaks to his innocence, as a guilty mind would have welcomed the opportunity to save himself foreseeable retribution, and with a fat reward to boot.

* * *

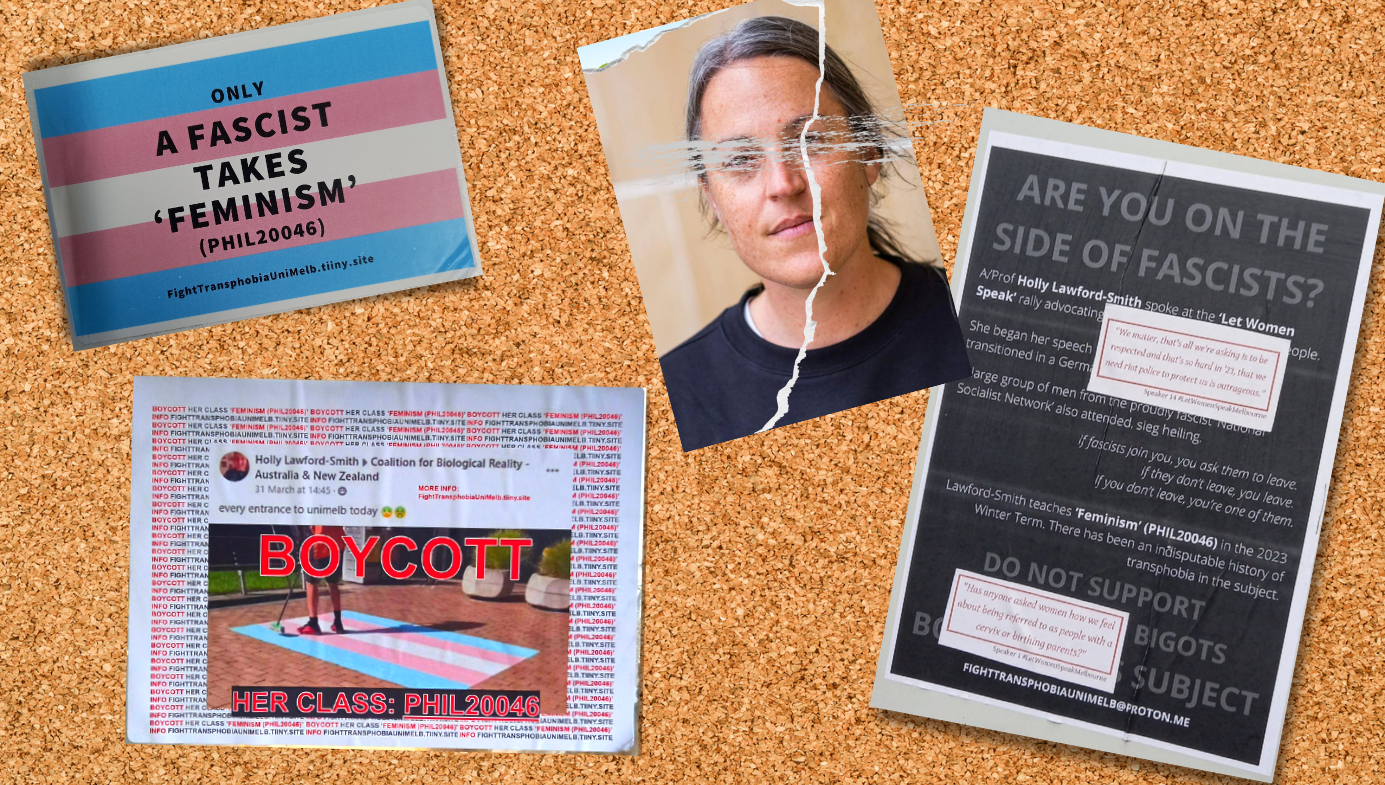

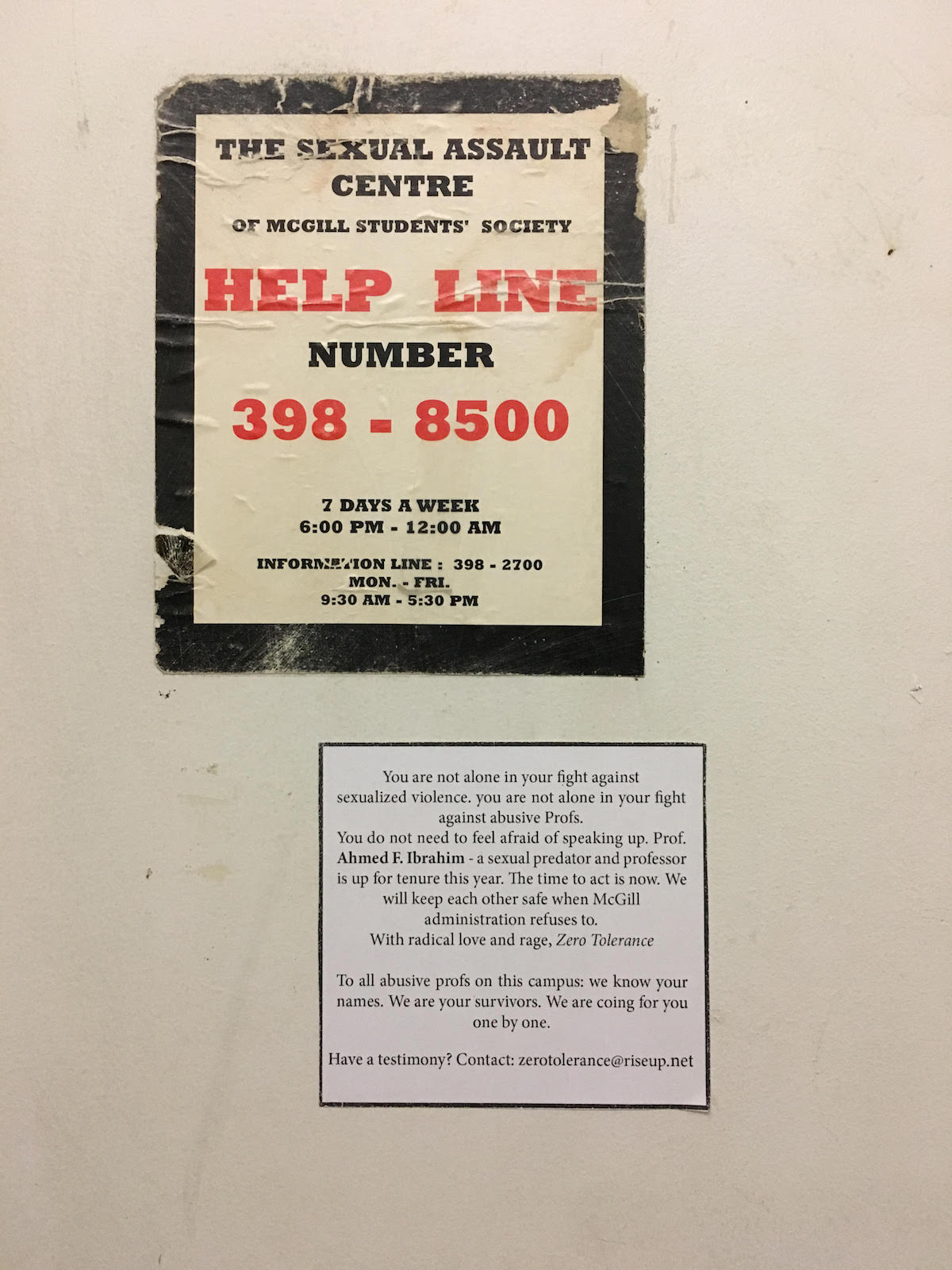

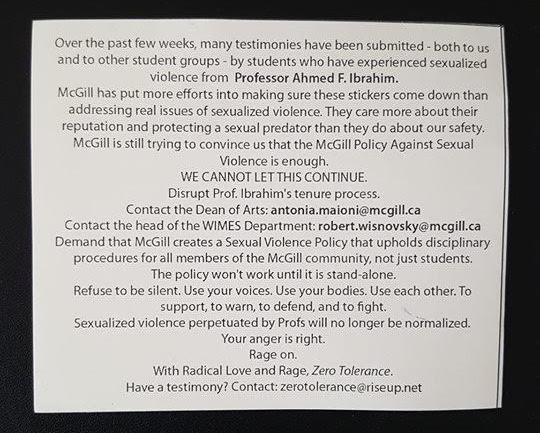

In September 2017, two months before the first meeting of the tenure committee, a group calling itself “ZeroTolerance” began a sticker campaign in the IIS women’s washrooms and elevators, naming Ibrahim as an abuser. The statement was also posted to a Facebook page titled “ZeroTolerance,” and it reads:

Have you had bad experiences with Prof. Ahmed F. Ibrahim? You’re not alone. He’s up for tenure this year. The time to act is now! Hold McGill responsible for the blind eye they turn to abusive professors. We will keep each other safe when our administration refuses to. With love and rage, Zero Tolerance. To all abusive profs on this campus: we know your names. We are your survivors. We are coming for you one by one. Have a testimony? Contact: [email protected]

Horrified, Ibrahim asked IIS Director Robert Wisnovsky, and a bit later Dean of Arts Maioni, to open an investigation into all rumoured allegations, but neither of them took any official action to contain the rumour fire. In contrast, the McGill Daily lent eager support to the campaign on October 2017 in an article by a McGill staffer featuring an anonymous accuser who describes office meetings with an unnamed professor, clearly meant to be Ibrahim. The complainant struggles hard to achieve #MeToo status, but her accusations are hardly eyebrow-lifting. For the core of her claim is that in these meetings the professor talked about his personal life and sat very close to her, giving her the impression, he was flirting with her.

I asked Ibrahim if he recognized the anonymous author or her story; he responded “There’s no truth to this at all and I have no clue who this is.” The thing about allegations like these is that the devil is always in the details. The anonymous author said the professor “would insist on keeping the door to his office closed.” While interviewing a colleague whose office is near Ibrahim’s, I asked if he had ever noticed indiscreet behaviour on Ibrahim’s part. He had not. In fact, he told me that he had specifically been irritated by Ibrahim’s practice of leaving the door open while meeting with students. Once, when he asked Ibrahim to shut it so that he wouldn’t have to listen, Ibrahim responded, “I can’t. I have a female student here.”

In true mobbing fashion, the extreme and racist allegations that Ibrahim was a typical Arabic misogynist and sexual predator simply do not add up. In fact the opposite is true. Ibrahim grew up in a patriarchal culture, but is the least patriarchal man one can imagine. In Egypt, he told me, he demonstrated against sexual harassment of women, and supported efforts to implement laws protecting women from sexual aggression. In 2014, his group’s activism resulted in the passage of tougher anti-sexual harassment laws by the Egyptian parliament. Unfortunately, part of the cruelty of academic mobbings is the refusal of the mob to see any redeemable feature in the target whether it exists or not.

In mid-November 2017, just prior to the first meeting of the Departmental Tenure Committee, WIMESSA sent a letter to Wisnovsky and Maioni, directly requesting that they deny Ibrahim tenure on grounds that a “significant number of students” avoid coming to the IIS “because of allegations of sexual misconduct.” Survivors of sexual trauma, they say, feel triggered by his “very presence.” Women students, they say, “feel at risk of sexual harassment.” While the letter is certainly damming in its thrust, it does not contain a single fact that would support any charge of actual misconduct on Ibrahim’s part.

Amidst this onslaught of disinformation, Najah would again step in to do the right thing and speak up against the treatment of Ibrahim. In a formal letter dated November 27, 2017, addressed to Professor Antonia Maioni, Dean of the faculty of Arts, and copied to Professor Wisnovsky, Najah would again firmly rebut Shamy’s article, tell the truth of what actually happened in the controversial classes of January 31 and February 2, 2017, and succinctly acknowledge the witch-hunt Ibrahim had endured.

In the letter, Najah states that Shamy, “quite strongly disliked Professor Ibrahim based on ideological differences” and that her own forcefully worded email to Ibrahim contained emotions that “were not truly representative of how I felt about what had transpired.” And most illuminating: “I felt the need to appease my friends at the time and, given the clique mentality of the group if I failed to hold the same beliefs as them, my loyalty and Muslim identity was questioned.”

As for Shamy’s accusations—that Ibrahim was “an internalized Islamophobe and constantly interrupts Muslim women in favour of white women,” Najah says, “this could not be further from the truth. I am a black Muslim woman and Professor Ibrahim has not ever interrupted me or made me feel less valued than my white female classmates. Quite the contrary.”

Indeed, “[t]he only interruptions made in class were when Sarah Abdelshamy, one of my friends, would take up the entire floor for long durations which did not allow other students to contribute to discussions….There is not one class where Sarah raised her hand and she was not given the floor to speak.” Later in the letter, Najah characterizes Shamy’s charge that Ibrahim treats white students better than Muslims as “an egregious misrepresentation of the truth.”

In direct contrast to Shamy’s allegation that Ibrahim disrespected students, Najah wrote:

While these moments in class were incredibly uncomfortable for me and many students who had expressions of discomfort on their faces, Professor Ibrahim would allow her (Shamy) to challenge him and was incredibly respectful. He would even propose books or articles to Sarah to gain further knowledge about the topics she questioned him about and her reply on one of those days was “Why are you suggesting I read about Jihad from a white person?”

Najah notes as well that she refused to move forward with filing a complaint against Professor Ibrahim within the Institute “even though she (Shamy) urged me to do so.” She adds that Ibrahim “has been one of the best Professors I have had the chance to learn from at McGill.”(“one of the best professors” or “the best professor” runs through five years of student comments on Ibrahim’s teaching like a mantra.) Najah’s letter unequivocally exposed Shamy’s actions for what they were: an absurd and unethical witch-hunt lead by a zealot who would stop at nothing to destroy the reputation of a good man, even if it meant acting like a high school student by posting lies about him in the University’s washroom stalls.

In an effort to mitigate the growing bias generated from within the department, Ibrahim requested the removal of three potentially biased ISS faculty members from his Departmental Tenure Committee. Wisnovsky granted Ibrahim’s request and replaced three of the members with tenured McGill faculty from outside the institute. To open the DTC’s first meeting, Wisnovsky prepared and read a statement to the outside faculty, dated November 26, 2017, instructing the ostensibly unbiased members of the DTC to make their decision strictly on the merits of Ibrahim’s tenure dossier. Now this is where things took a sharp turn into the absurd. In doing so, Wisnovsky then disclosed to the DTC the exact extraneous details that he states should have no bearing on the process.

Wisnovsky opened his speech by stating that he was not acting “arbitrarily or hastily” and that he had consulted with McGill’s lawyers and the Provost on how to fulfil his duties as DTC Chair. He then stated, “As most if not all of you know, there have been numerous rumors surrounding Professor Ibrahim, and a great deal of tension in the Institute concerning whether or not he should be awarded tenure.” In short, Wisnovsky paints the tenure application as a campus wide controversy that now involves not only top administrators, but also department wide “tension” and even McGill general counsel.

He then reminds the members of the DTC that, “The fact that Professor Ibrahim was subject to disciplinary sanction cannot be used as a basis of judgment when each of us decides how to rank him in his three academic duties of research, teaching, and service.” But in the same paragraph he discloses the exact details of Ibrahim’s relationship with MG and the sanction he received for not disclosing that relationship.

Wisnovsky then informed members of the DTC that Ibrahim requested the removal of three faculty members for bias and tells them that this cannot be used against him in the evaluation of his tenure application. In perhaps the most damaging and biased statement of them all, Wisnovsky stated, “Two of those tenured Institute colleagues were targets of the tenure candidate’s internal and external harassment complaints.” [emphasis mine] Here Wisnovsky has chosen specific and careful language, perhaps through the guidance of McGill’s general counsel, that leaves the distinct impression that Ibrahim’s efforts to receive a fair and unbiased review of his tenure was actually an act of aggression and that the removed faculty were his “targets.”

Wisnovsky then told the DTC that, as an added precaution, he personally chose to remove his own wife as a possible member of the committee because “a similar apprehension of conflict of interest was possible in her case too, given that we are married.” What’s of course absurd about this self-flagellation in which Wisnovsky attempts to add his own wife to the list of Ibrahim’s “targets,” is that by acknowledging that his wife may be biased by proximity to him he is more or less confessing his own bias.

To round things off, Wisnovsky concludes his opening statement to the DTC by stating “I realize that this is all a lot to absorb.” Now of course the question we must ask is this: why is there anything to “absorb” at all in a statement that Provost Manfredi stated would “ensure that the DTC would set aside any information outside of the tenure dossier.” If Wisnovsky’s statement was intended to focus the DTC on Ibrahim’s actual application, as is policy, then it would have been a neutrally written document that contained no details of what needed to be restricted. The only thing that would need to be “absorbed” would be the rules and instructions that the DTC act ethically and adjudicate Ibrahim’s application with the impartiality that the process required.

In short, given that Wisnovsky revealed information likely to encourage bias to the DTC members, information that they were not permitted to know according to McGill’s own guidelines, the tenure rejection to follow may be said to be, in ethical terms, the fruit of a poisoned tree. On November 30, 2017, three days after the dated draft of Wisnovsky’s script, Ibrahim received notice that his application was “tending to negative.”

In 2014, when renewal of his contract was up for consideration, the IIS evaluation sent to Provost Christopher Manfredi, then Dean of Arts, was lavish in its plaudits. Citing Ibrahim’s contributions in detail, it concludes: “[A]fter only two years, it is clear that the hiring of Ahmed Ibrahim was fortuitous; he has upheld the strong tradition of the study of Islamic law at the Institute,” and “Prof. Ibrahim has compiled an impressive research and teaching record that would already count as superior in a tenure recommendation.”

Since 2014, Ibrahim’s teaching rankings have actually improved and the rate of his publishing has accelerated. An external reviewer’s report stated that, “Dr. Ibrahim’s work is of the highest academic caliber; he has achieved the rare feat of both providing theoretical heft to an important and under-theorized area of Islamic law, and changing how we think of Islamic law as a discipline.”

In the last five years, for example, along with journal contributions, Ibrahim has published two books, the first of which was received with respect and praise by international scholars, the second of which was published this past July by Cambridge University Press. This is quite exceptional for a scholar at this stage of his career, and certainly extraordinary at McGill’s IIS. In addition to which, his service record to McGill and the larger community has been so exemplary that this past January, Ibrahim was nominated for the McGill Principal’s prize for public engagement through media.

His student evaluations tell a similar story of excellence. In his five years of teaching, 327 students evaluated Ibrahim as a professor who invited them to share their views freely, compared with nine students whose 13 comments expressed disappointment on that point. As the DTC’s Minority Report notes, “It strikes us as suspicious that all of the 13 negative comments on Professor Ibrahim’s failure to create a safe learning environment for women students in particular appear for the first time in five years in winter 2017 in the comments on his Central Questions in Islamic Law (ISLA 383), the last semester from which student evaluations would count towards tenure.”

In response to the denial of Ibrahim’s tenure, 80 of the approximately 400 students who studied under him signed a counter-petition in Ibrahim’s support, urging McGill to exercise due process, change course, and grant Ibrahim tenure. These students put their names to this petition knowing there might be both social and professional blowback for doing so. A number of them also wrote glowing testimonials and sworn affidavits on Ibrahim’s behalf. Taken together, one finds in these letters the portrait of an environment in which everyone walks on eggshells when dealing with gender and Islam.

I communicated by telephone and email, or met in person with a number of present and former students, recommended to me by Ibrahim as counterpoint to his detractors. Common themes emerged and these former students spoke of Ibrahim in glowing terms. One who I will call “Olivia,” said she could sense hostility to Ibrahim from his colleagues. She wrote me: “When speaking with one or two other professors about how much I enjoyed Islamic studies, and them having asked me which classes in specific, upon hearing Professor Ibrahim’s name, they pulled a certain face…Whilst Professor Ibrahim encouraged us to think about taking other courses in the faculty, including those of other professors, the same cannot be told the other way around.”

In contrast to their glowing testimonials of Ibrahim, these same students describe Shamy as, variously, “a vicious individual” who had “a personal vendetta against Professor Ibrahim” and generally “not nice to be around if you are not a person of colour.” One student recounted that Shamy “screamed at the professor and at the students very aggressively, saying you don’t have the right to speak.”

Despite all the evidence indicating a process stacked against him, the denial of Ibrahim’s tenure was recommended by the Department Tenure Committee and accepted without demur by the University Tenure Committee (UTC) and the Provost. For Ibrahim, the denial was a staggering professional dishonour, as well as a psychological and emotional blow from which he may never wholly recover. With two children to support (amicably divorced, Ibrahim and his ex-wife share parenting), and further burdened by the shame of curtailing remittances on which his Cairo family depends, Ibrahim finds it difficult to concentrate on his research at a time when he must now start his career over from scratch.

It should go without saying, but in Ibrahim’s case—given the entirely rumour-based reputation with which he is now saddled—it needs to be said: No complaint of any act of impropriety, sexual or otherwise, has ever been laid against him at McGill University or anywhere else. When his contract expires in June of 2019, Ibrahim will be unemployed and unemployable in his academic field.

In July of 2018, Ibrahim filed a $600,000 defamation lawsuit against Shamy and Pasha Khan. His lawyer, Julius Grey, a familiar and respected name in Quebec human rights litigation, told me that he considers the evidence for the baseless mobbing campaign that ended Ibrahim’s academic career “solid,” adding that (in general) in academia, “the presumption of innocence seems to have gone completely by the boards” and “mobbing appears to be authorized and effective.”

Ibrahim has also appealed his tenure denial to Professor Peter Grutter Vice-Chair, University Appeals Committee. In a letter to Grutter requesting that he dismiss Ibrahim’s appeal, Manfredi defends his own position in the process, claiming that he was not biased.

If he was not biased, what, then, happened to change Manfredi’s mind between his reception of the IIS’s unconditional commendation of Ibrahim in 2014 and his May 2017 offer to purchase Ibrahim’s self-immolation? How does he justify the extraordinary conflict of interest he then put himself in by signing off on a tenure denial as though he had been persuaded by the Majority Report, when in fact he had apparently already made up his mind that Ibrahim had to go a year earlier?

Manfredi’s denial of bias is untenable. His buyout offer to Ibrahim, received months ahead of the formal tenure process, is tantamount to an admission that the fix was already in, and that everything to follow was the academic version of Kabuki theatre. In this tragedy, many individuals conspired to bring their targeted scapegoat low, but they could not have, and would not have, succeeded if the institution that had the moral obligation and the power to see academic justice done, had followed its own tenure guidelines with probity.

The removal of a politically incorrect thorn in its side may have been convenient for McGill in the short term, but over the long term will likely be viewed with chagrin as not worth the ineradicable stain of institutional dishonor Ibrahim’s tenure denial represents. Ibrahim’s hearing by the tenure appeal panel is scheduled for October 17. For anyone at McGill to backtrack now and admit that the tenure process was biased would be an act of courage in the face of a process that has been marred by cowardice, secrecy, and duplicity. Yet Ibrahim’s fate and McGill’s good name hang on that faint hope.

Both Professor Wisnovsky and Provost Christopher Manfredi declined an opportunity to comment for this article.