Books

From Party of Ideas to Party of Dittoheads

Stupidity is not an accusation that could be hurled against such early Republicans as Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, Elihu Root and Charles Evans Hughes.

Editor’s Note: This is excerpted from The Corrosion of Conservatism: Why I Left the Right, by Max Boot, 288 pages, Liverlight (October 9, 2018).

The modern history of the Republican Party is a warning to be careful of who you pretend to be, because sooner or later you will become that person. Republicans have long flirted with populism, conspiracy-mongering, and know-nothingism. This is why they became known as the “stupid party.” Stupidity is not an accusation that could be hurled against such early Republicans as Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, Elihu Root and Charles Evans Hughes. But by the 1950s, it had become an established shibboleth that the “eggheads” were for Adlai Stevenson and the “boobs” for Dwight D. Eisenhower—a view endorsed by Richard Hofstadter’s 1963 book Anti-Intellectualism in American Life, which contrasted Stevenson, “a politician of uncommon mind and style, whose appeal to intellectuals overshadowed anything in recent history,” with Eisenhower—“conventional in mind, relatively inarticulate.” The Kennedy presidency, with its glittering court of Camelot, cemented the impression that it was the Democrats who represented the thinking men and women of America.

Rather than run away from the anti-intellectual label, Republicans embraced it for their own political purposes. In his “time for choosing” speech, Ronald Reagan said that the issue in the 1964 election was “whether we believe in our capacity for self- government or whether we abandon the American Revolution and confess that a little intellectual elite in a far-distant Capitol can plan our lives for us better than we can plan them ourselves.” Richard M. Nixon appealed to the “silent majority” and the “hard hats,” while his vice president, Spiro T. Agnew, issued slashing attacks on an “effete corps of impudent snobs who characterize themselves as intellectuals” and the “nattering nabobs of negativism.” (The latter phrase, ironically, was written by speechwriter William Safire, who would go on to establish a reputation as a libertarian columnist and grammarian for the conservatives’ bête noire, The New York Times.) William F. Buckley Jr. famously said, “I should sooner live in a society governed by the first 2,000 names in the Boston telephone directory than in a society governed by the 2,000 faculty members of Harvard University.” More recently, George W. Bush joked at a Yale commencement: “To those of you who received honors, awards and distinctions, I say, well done. And to the C students I say, you, too, can be president of the United States.”

Many Democrats took all this at face value and congratulated themselves for being smarter than the benighted Republicans. Here’s the thing, though: the Republican embrace of anti-intellectualism was, to a large extent, a put-on—just like their espousal of far-right rhetoric on the campaign trail. In office they proved far more moderate and intelligent. Eisenhower may have played the part of an amiable duffer, but he may have been the best prepared president we have ever had—a five-star general with an unparalleled knowledge of national security affairs. When he resorted to gobbledygook in public, it was in order to preserve his political room to maneuver. Reagan may have come across as a dumb thespian, but he spent decades honing his views on public policy and writing his own speeches. Nixon may have burned with resentment of “Harvard men,” but he turned over foreign policy and domestic policy to two Harvard professors, Henry A. Kissinger and Daniel Patrick Moynihan, while his own knowledge of foreign affairs rivalled Ike’s.

There is no evidence that Republican leaders have been demonstrably dumber than their Democratic counterparts. During the Reagan years, the GOP briefly became known as the “party of ideas” because it harvested so effectively the intellectual labor of conservative think tanks like the American Enterprise Institute and the Heritage Foundation, and publications like The Wall Street Journal, National Review, and Commentary. Scholarly policymakers such as George P. Shultz, Jeane J. Kirkpatrick, and Bill Bennett held prominent posts in the Reagan administration, a tradition that continued into the George W. Bush administration— amply stocked with the likes of Paul D. Wolfowitz, John J. Dilulio Jr., and Condoleezza Rice. This was the Republican Party that attracted me as a teenager in the 1980s and maintained my loyalty for decades to come.

In recent years, however, the Republicans’ relationship to the realm of ideas has become more and more attenuated, as talk-radio hosts and television personalities have taken over the role of defining the conservative movement. The Republicans’ populist pose has become all too real. A sign of the times is that Bill Bennett, possessor of a PhD from the University of Texas at Austin and a JD from Harvard Law School, stoops to attack George Will, a Princeton PhD, for his criticism of Vice President Mike Pence, by mockinghis “penchant for writing columns filled with big words that most Americans never use and can’t even define.” Presumably, a dictionary counts as elitist foppery.

The turning point in the Republican transformation was the rise of Sarah Palin after John McCain made the mistake of selecting her as his running mate in 2008—a move that he later regretted. (He wished that he had selected his friend, Democratic Senator Joe Lieberman of Connecticut, instead.) Palin showed that she was a dim bulb when she was asked during the campaign which sources she relied on for the news. Caught off-guard, she could not answer, and had to deflect with unconvincing generalities: “I have a vast variety of sources.” This was akin to an admission that she did not read newspapers or magazines beyond, possibly, Field & Stream or Guns & Ammo. I can’t say I was terribly surprised. As a McCain foreign policy advisor, I had briefed her and found her to be uninterested in foreign policy issues. (The most memorable takeaway from our meeting at a midtown Manhattan hotel was that she wore earrings in the shape of the state of Alaska.)

Palin’s lack of preparation for high office could perhaps be excused as the provincialism of a small-state governor who had not asked for the national spotlight. (Alaska’s population is smaller than San Francisco’s.) But rather than return to her duties after the election, or try to educate herself on the issues, Palin resigned as governor in 2009 and sought to cash in on her celebrity by becoming a full-time media personality. She proceeded to litter the land with inanities that have few parallels in our history. She even invented a new word—“refudiate” (by conflating “repudiate” and “refute”)—and tried to suggest that she was a Shakespearean sage who was enlarging our vocabulary. A sample of Palin’s other bizarre statements: Well, if I were in charge, they would know that waterboarding is how we’d baptize terrorists; But obviously, we’ve got to stand with our North Korean allies; We can send a message and say, ‘You want to be in America, A) You’d better be here legally or you’re out of here. B) When you’re here, let’s speak American’; I think on a national level, your Department of Law there in the White House would look at some of the things that we’ve been charged with and automatically throw them out. (There is no “Department of Law” in the White House, or anywhere else.)

Conservatives applauded this inanity, making Palin one of the biggest stars on the right-wing rubber-chicken circuit, until she was eclipsed by the rise of the even more vulgar and vacuous Donald Trump. Their rise indicates that the GOP truly has become the stupid party. Its primary vibe has become one of indiscriminate, unthinking, all-consuming anger.

That anger is stoked by the “alternative media” of the right, whose origins can be traced back to the founding of the newspaper Human Events in 1944, Regnery Publishing in 1947, and National Review in 1955. In later years, two publishing houses— Basic Books and The Free Press—played an important role in producing works of conservative scholarship, including many tomes that I read while growing up, such as Alan Bloom’s The Closing of the American Mind, Charles Murray’s Losing Ground: American Social Policy, 1950–1980, George Gilder’s Wealth and Poverty, and James Q. Wilson’s Bureaucracy.

But the alternative media did not become a mass phenomenon until Ronald Reagan’s Federal Communications Commission decided in 1987 to stop enforcing the “fairness doctrine,” a 1949 policy that required all television and radio broadcast outlets to present both sides of controversial public issues. This deregulatory move made possible the debut in 1988 of Rush Limbaugh’s national radio show, which did not pretend to offer anything but a conservative perspective on the news. Revealingly, Limbaugh called his fans Dittoheads, because they mindlessly echoed his prejudices—or he theirs; the pandering went both ways. Many other right-wing “talkers” followed.

I worried about the impact of the talk-show populists as far back as 1994, when I wrote a Wall Street Journal op-ed headlined “Down with Populism!” shortly after Republicans had taken control of the House for the first time in 40 years. I argued that the GOP should not “‘Rush’ to embrace talk show democracy” because of the dangers of mob rule. I quoted my boyhood favorite, H. L. Mencken: “Least of all do I admire the puerile, paltry shysters who constitute the majority of Congress. But I confess frankly that these shysters, whatever their defects, are at least appreciably superior to the mob.” The expression of mob rule I was most worried about was a new conservative TV network called National Empowerment Television (which has long since faded away). I had no idea that Fox News Channel would be founded in two years’ time, and that it would make my worst fears of populism run amok come true. Coincidentally, 1996 also was the year that the Drudge Report, an online bulletin board for right-wing fever dreams, was launched.

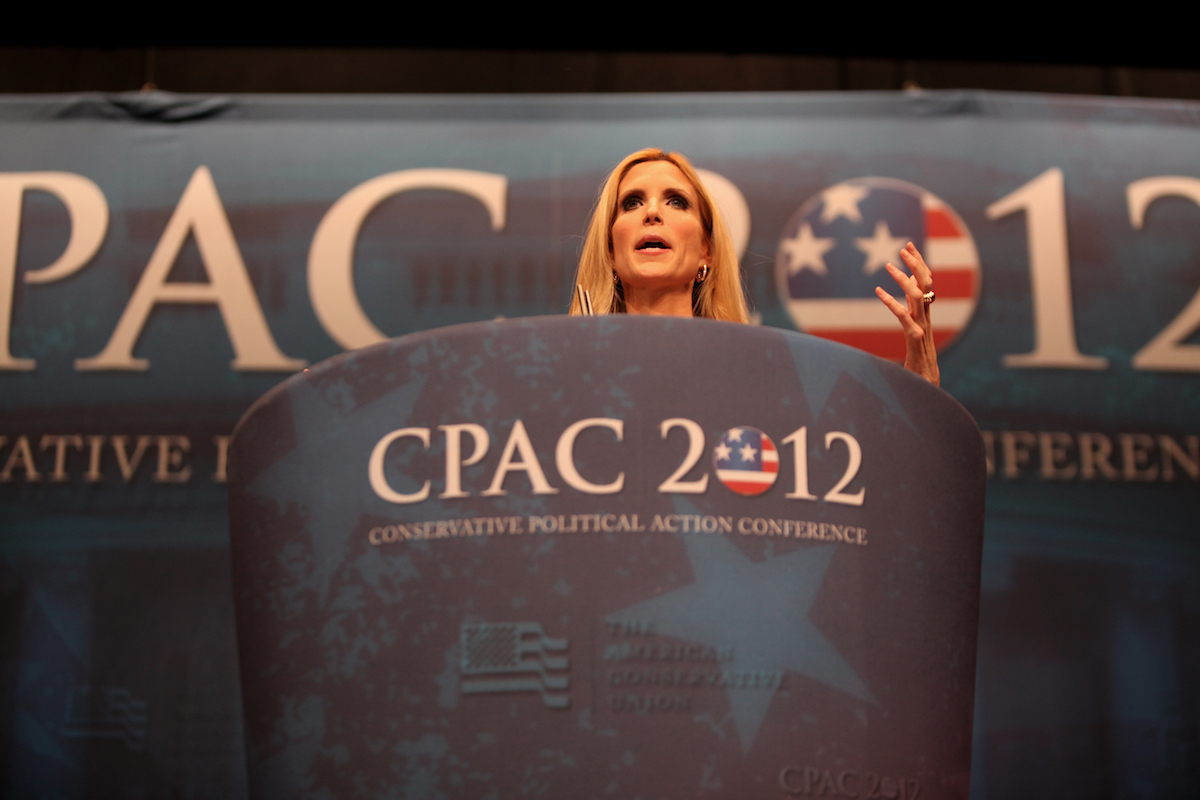

Limbaugh, Fox, and Drudge still remain three of the most popular outlets on the right, but they have been joined by radio hosts such as Mark Levin and Michael Savage, celebrity authors and talking heads such as Ann Coulter, Milo Yiannopoulos and Dinesh D’Souza, and websites such as Breitbart News, TheBlaze, Infowars, and Newsmax. The original impetus for these outlets was to offer a different viewpoint that people could not get from the more liberal TV networks, newspapers and magazines. But soon, the alternative media moved from propounding their own analyses to concocting their own “facts,” incubating of outlandish conspiracy theories such as “Hillary Clinton murdered Vince Foster,” “Barack Obama Is a Muslim,” or even “Michelle Obama Is a Man.”

The career of Dinesh D’Souza, one of the right’s biggest media stars in spite of being a convicted felon (who has now been pardoned by President Trump), is indicative of the downward trajectory of conservatism. After a checkered career in conservative journalism at Dartmouth, he made his name with Illiberal Education, a well-regarded 1991 book published by The Free Press, which denounced political correctness and championed liberal education. Then he wrote a widely panned 1995 book, also from The Free Press, claiming that racism was no more. It was all downhill from there. In 2014 he pleaded guilty to breaking campaign finance laws. More recently, as the Daily Beast notes, he has become a conspiratorial crank who has suggested that the white supremacist rally in Charlottesville was staged by liberals and that Adolf Hitler, who sent 50,000 homosexuals to prison, “was NOT anti-gay.”

D’Souza managed to sink even lower in February 2018, by mocking stunned Parkland school-shooting survivors after the Florida legislature defeated a bill to ban assault weapons: “Worst news since their parents told them to get summer jobs.” He was joined in this repugnant japery by Laura Ingraham, who made fun of school-shooting survivor David Hogg for not getting into the college of his choice (she later apologized), and by Jamie Allman, a Sinclair broadcasting commentator who was fired for saying that he would like to sexually assault Hogg with a “hot poker.”

It is hard to imagine anything more cruel and heartless, but for these opportunists it’s all in a day’s work. As D’Souza wrote in his 2002 book Letters to a Young Conservative, “One way to be effective as a conservative is to figure out what annoys and disturbs liberals the most, and then keep doing it.” That, in a nutshell, is the credo of today’s high-profile conservatives: Say anything to “trigger” the “libtards” and “snowflakes.” The dumber and more offensive, the better. Whatever it takes to get on (and stay on) Fox News and land the next book contract. Hence outbursts such as this tweet from Fox News’ 25-year-old blonde commentator Tomi Lahren: “Let’s play a game! Go to Whole Foods, pick a liberal (not hard to identify), cut them in line along with 10–15 of your family members, then take their food. When they throw a tantrum, remind them of their special affinity for illegal immigration. Have fun!” (I only mention Lahren’s appearance because the employment of female hosts with short skirts, and preferably blonde hair, is an integral part of Fox’s strategy to attract the elderly white men who form its core audience.)

Such rhetorical sallies are as lucrative as they are illogical. D’Souza has grossed tens of millions of dollars with documentaries attacking Hillary Clinton and Barack Obama as anti-American subversives. Sean Hannity makes roughly $30-million a year and flies on his own private jet, even while railing against “overpaid” media elites.

Naturally, just as drug addicts need bigger doses over time, these outrage artists must be ever more transgressive to get the attention they crave. Ann Coulter’s book titles have gone from accusing Bill Clinton of High Crimes and Misdemeanors to accusing all liberals of Treason, of being Godless and even Demonic. Her latest assault on the public’s intelligence was called In Trump We Trust: E Pluribus Awesome!

If this is what mainstream conservatism has become—and it is—count me out.