Top Stories

When Censorship Is Crowdsourced

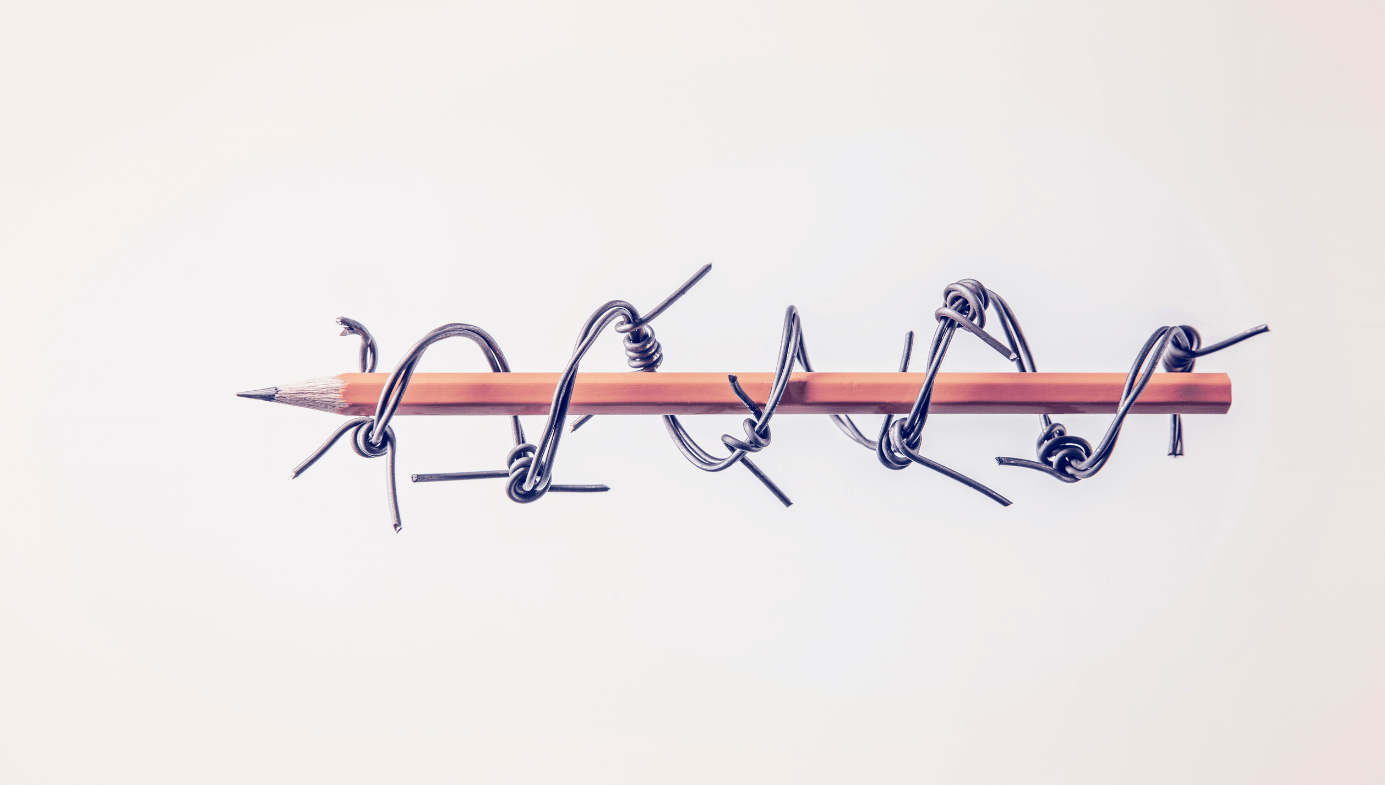

The very writers, publishers, poets, musicians, comedians, media producers and artists who once worried about being muzzled by the government are now self-organizing on social media (Twitter, especially) to censor each other.

Editor’s note: The text that follows is adapted from a speech delivered recently by the author to the Montreal Press Club.

On the op-ed page of The New York Times, former Central Intelligence Agency general counsel Jeffrey Smith recently argued that Donald Trump’s decision to revoke the security clearance of former CIA director John Brennan “violated Mr. Brennan’s First Amendment right to speak freely.” It’s an intriguing thesis. And, being a former lawyer who once wrote long law school essays about constitutional freedoms, I read it with keen interest.

But I also felt a twinge of nostalgia as I parsed Smith’s lawyerly arguments. Notwithstanding the nature of Mr. Trump’s treatment of Mr. Brennan, the gravest threats to free speech in democratic countries now have little or nothing to do with government action (which is what Constitutions serve to restrain). And with few exceptions, public officials now sit as bystanders to the fight over who can say what.

Last month, Facebook, Apple and Google deleted gigabytes of video, audio and text content from Alex Jones’s Infowars web site—part of a larger speech-pruning process that is applied every day to numerous (less prominent) wing nuts who, like Jones, blur the line between conspiracism and hate-mongering. Twitter, on the other hand, allowed Jones’s Infowarsand personal accounts to remain active—but then abruptly changed course in early September. Why? Who knows. All of these online services make users sign on to terms of-service agreements that prohibit abusive speech and the advocacy of violence. But the lines are blurry, and there’s lots of wiggle room. And even if there weren’t, it wouldn’t matter anyway since these are private companies that can pretty much ban anyone they want, so long as they’re willing to accept the blowback from remaining users. These companies aren’t making legal decisions when they block or don’t block one of their users. They’re effectively taking political positions on what is and isn’t beyond the bounds of mainstream discourse.

And since social media is the way we all communicate with one another every day, their power over information flows has become enormous. Taken together, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, Twitter’s Jack Dorsey, Reddit’s Alexis Ohanian and Google’s founding duo of Larry Page and Sergey Brin have far more impact on what we see and hear than any government.

If you are, like me, a middle-aged person who has been concerned about protecting free speech since your college days, these developments will have a profoundly disorienting effect. When I was a university student in the early 1990s, it always was assumed that the primary threat to free speech was government—especially government in the Big Brother form that George Orwell had taught us to expect and fear.

This model of censorship and counter-censorship persisted into this century. In the years after 9/11, for instance, conservatives in my own country, Canada, became consumed with the question of what could and could not be said about militant Islam under Canadian human-rights laws. In the process, we made folk heroes out of Ezra Levant and Mark Steyn, who were willing to thumb their noses at provincial bureaucrats whose diktats truly did seem inspired by a desire to censor right-wing ideology.

Some of these battles are still being fought in obscure tribunal boardrooms. But for the most part, they’re yesterday’s drama. Levant and Steyn both published their anti-Islamist manifestos in national print magazines. While one of those magazines still exists, albeit in reduced form, the real to and fro of ideological debate now takes place on borderless electronic fora (such as this one) whose content is, within some limits, free of any government oversight. Compared to the situation a decade ago, the source of censorship in our lives has been massively decentralized.

In many creative spheres, in fact, censorship hasn’t just been decentralized. It’s been crowdsourced. Which is to say: The very writers, publishers, poets, musicians, comedians, media producers and artists who once worried about being muzzled by the government are now self-organizing on social media (Twitter, especially) to censor each other. In its mechanics, this phenomenon is so completely alien to top-down Big Brother-style censorship that it often doesn’t feel like censorship at all, but more like a self-directed Inquisition or Chinese communist “struggle session.” However, the overall effect of preventing the propagation of stigmatized ideas is achieved all the same.

Consider, for instance, the current preoccupation with cultural appropriation—a doctrine that, in my country, now serves to dictate what subjects Canada’s novelists and poets are permitted to take on in their work. In some cases, the process by which individual artists assess whether they are or aren’t allowed to tell a particular story truly does resemble the bureaucratic application process for a government program—as I showed back in January, when I described the bizarre saga of novelist Angie Abdou, who was repeatedly forced to submit her novel to various indigenous authorities before publication (and even then was hounded and attacked because she had dared to voice a young First Nations character). But it’s important to remember that no actual government censor had any involvement in Abdou’s case. The effort to censor her was entirely crowdsourced among other members of the literary community.

Or, to take a fresh example, take the case of Shannon Webb Campbell, a young Canadian author who recently was slated to release a collection of poetry through a small Toronto-based publisher called Book*hug. (The publisher’s original name was Bookthug, but this was changed in 2017 amid complaints that “thug” was racist—which should tell you all you need to know about the leftist politics of both Book*hug and the art-house Canadian literary community within which it operates.) Indeed, the book already had been printed and readied for shipment when Book*hug abruptly decided to yank the volume from its catalog, pulp all physical copies, and delete Webb Campbell’s web page from its site (visitors received a 404 error code). They also published an effusive apology on their main site, declaring that the book was “causing pain and trauma to members of Indigenous communities.”

The reason for this, Book*hug went on to disclose, was that Webb Campbell—who herself is partly indigenous—had written about the death of another indigenous person in a way that “does not follow Indigenous protocol with regard to these matters.” The nature of these “protocols” was not explained.

The same day, Webb Campbell published a lengthy confession on her Facebook page, in which she confessed to various thought crimes, especially her failure to secure permission from family members before presuming to describe the death of an indigenous woman. She also pleaded for mercy on the basis that “as a mixed Mi’kmaq-settler writer, who did not grow up within my culture due to colonialism and the ripple effects of intergenerational trauma, I was unaware around the protocol of material of this nature. I feel very ashamed by my lack of knowledge.” Webb Campbell also pledged to deposit the poem into a sort of memory hole, promising that the poem would never again be spoken aloud by her own lips.

I am not a poet, nor indigenous, nor a member of the broader Canadian literati. I had never heard of Webb Campbell, nor Book*hug. Yet I found myself incensed on Webb Campbell’s behalf. In what world do poets have to ask permission to create verse about others? Did Homer run his Patroclus death scene past Menoetius and Philomela? Did John McCrae run In Flanders Field past the family of his late friend Alexis Helmer or the other victims at Ypres?

Yet, amazingly, not a single prominent member of the Canadian literati was willing to publicly condemn this public shaming of Webb Campbell by her own publisher. And to the extent the media covered her de-platforming, it was airily portrayed as a teachable moment that showed how artists all needed to be more sensitive about what they wrote. The CBC, in particular, uncritically included the preposterous accusation that “publications like Webb-Campbell’s contribute to a narrative that normalizes violence against Indigenous women and girls.”

Nor, as far as I can determine, did a single CanLit heavyweight utter a public complaint when Webb Campbell was abruptly bounced from April’s Ottawa Writers Festival. At that event, Webb Campbell has been scheduled to share the stage with the former president of a prominent NGO that purports to support the right to free expression. When I found myself seated beside this august figure at a Toronto dinner party in the days before the festival, I asked whether he intended to raise his voice against Webb Campbell’s treatment. His response was that he planned to run this thorny issue past an indigenous woman he knew—a wise old soul, by his description, who would tell him “exactly what to do” (which, as things apparently turned out, was nothing). Days later, when I made myself a pest by tweeting directly at the literary festival about all of this, the reply came: “Baffled by your need to speak for those who can and do speak so well for themselves—especially those who have not asked for your help or advice. If [Webb Campbell] said she was silenced or censored, we would have had [her] here even without the book.”

While I rarely like to concede defeat in a Twitter smackdown, I had to admit that this festival’s social-media people had me dead to rights—for it’s absolutely true that Webb Campbell wasn’t censored in any formal sense. None of the events I am describing here involve the government. Nor was Webb Campbell muzzled in any way by Book*hug, which presumably would have been only too happy to have her publish her book elsewhere. Webb Campbell could have put the controversial poem on Facebook, or Tweeted it out line by line. But she did none of this. Instead, she swallowed her pride, signed the confession that had been placed in front of her, and prayed that she would be readmitted into CanLit’s good graces—which, in fact, now seems to be happening, following what seems to have been an elaborate months-long display of performative contrition on Webb Campbell’s part. (The festival’s flacks also were correct that Webb Campbell never asked for my help or advice. Just the opposite in fact: I suspect that the poet would have opposed my involvement, since my views on free speech (and a dozen other topics) mark me as an outsider to her caste, and one badly tainted by cultural wrongthink.)

One thing about Nineteen Eighty-Four that does still ring true about the current age of crowdsourced censorship is the reverse classism at work. In Orwell’s Oceania, the intellectual class is scrutinized relentlessly for the slightest deviation in thought or speech, while “proles” are free to wallow in astrology, smut and sentimental storytelling.

There was even a whole sub-section—Pornosec, it was called in Newspeak—engaged in producing the lowest kind of pornography, which was sent out in sealed packets and which no Party member, other than those who worked on it, was permitted to look at.

The same principle applies in broad form today. Canadian tabloids publish material every day that would be deemed offensive to Ottawa Writers Festival types in all sorts of ways. But with rare exceptions, it gets a pass, because it is seen, in effect, as a sort of ideological Pornosec. The world of Canadian poetry, on the other hand, is a tiny rarefied world run by, and for, a few hundred Canlit Party members—all relentlessly scrutinizing one another for ideological heresies through the panopticon of social media. In this environment, Webb Campbell’s status as a reliably leftist, thoroughly woke poet who proclaimed her guiding light to be “decolonial poetics” was not a mark in her favor. Just the opposite: It confirmed her status as a full Party member, and therefore subject to all the ideological strictures applicable thereto. When the scarlet letter is sewn upon such a specimen by one publisher within the tiny incestuous world of Canadian poetry, it is sewn upon her by all. And while it was once imagined that artists and writers had a special duty to speak out against censorship, dogma and speech codes, they are now conditioned to believe that their highest duty is toward avoiding offense and staying in their lane.

This, in capsule form, is how crowdsourced censorship works in the literary field. And analogous stories could be told about academia and other creative métiers. It is up to the government to maintain a free marketplace of ideas. But freedom from government censorship doesn’t mean much when the stall-owners in the marketplace of ideas organize their own ideological protection rackets to drive one of their own out of business. Venerable groups that once led the fight for free speech and freedom of conscience, such as PEN and the ACLU, seem completely unequipped to deal with the new threats. Their entire organizational culture always has been directed at pushing back against government monoliths, not decentralized mob subcultures.

But the fact that government has no direct role in this new kind of censorship does not mean that public policy can’t be part of the solution. For while it’s true that government isn’t directly engineering these newly emergent forms of crowdsourced speech suppression, the current public funding model can indirectly encourage them.

The reason Book*hug can pulp Shannon Webb Campbell’s book without worrying much about lost readers or earned revenue is that, to a rough order of magnitude, they don’t have any readers or earned revenue. Like most small, high-concept book publishers in Canada, Book*hug is overwhelmingly dependent on government subsidies, which are what allow it to publish obscure manifestoes and poetry volumes that, outside of copies assigned to review, libraries, friends and family, might be expected to sell a few hundred copies.

Or fewer.

I recently consulted an online index that tracks Canadian book sales. For the latest Book*hug releases, the median number of books sold, per title, seems to be about 60. The tracking service does not claim to capture all book sales, estimating its accuracy at about 85 percent. (Direct sales at book-launch events, for instance, may escape capture in the data.) So let us be generous and assume that the median book sells 100 copies, or even double that. It doesn’t matter: In commercial terms, this is a non-entity. Which means there really is little or no financial penalty to be suffered if Book*hug publishes, or doesn’t publish, Shannon Webb Campbell instead of some other author. Everyone in this heavily subsidized subculture is playing with house money—as are the niche literary journals run by charitable entities (including one where I briefly served as editor). And the real asset to be husbanded in all these places isn’t the affection of readers—there often aren’t any—but rather the editors’ reputation for ideological purity among peers, donors and Twitter followers.

By way of counterexample: It’s notable that when the Canliterati attacked novelist Joseph Boyden after he was accused of falsely inflating his indigenous bona fides, his publisher, Penguin Random House Canada, stuck by him—perhaps because he is a famous author whose books are actually bought and read. But even at these large publishing houses, where titles are picked to sell in stores instead of to pose with at book launches, the inquisition has its agents. One editor, for instance, told me he’d love to recruit famed novelist Steven Galloway, following the release of information showing that he’d been railroaded on false rape claims at the University of British Columbia. But doing so, he explained, was impossible, at least for now, because he’d catch hell for it on social media. What matters in a witch hunt isn’t whether you believe someone is a witch—it’s whether your colleagues do (or, at least, pretend to).

None of this is entirely new, of course. There have been other periods in which writers and artists have crowdsourced their own censorship. This included the Red Scare in the United States; and the interwar period in Europe, when Orwell’s peers were expected to line up behind the socialist (and then communist) dogmas of the period. Putting aside the crushing effect on morale and social relationships among writers, Orwell noted, this also served to turn an uncountable number of writers into babbling propagandists.

“Few if any Russian novels that it is possible to take seriously have been translated for about fifteen years,” Orwell wrote in The Prevention of Literature.

In western Europe and America, large sections of the literary intelligentsia have either passed through the Communist Party or have been warmly sympathetic to it, but this whole leftward movement has produced extraordinarily few books worth reading. Orthodox Catholicism, again, seems to have a crushing effect upon certain literary forms, especially the novel. During a period of three hundred years, how many people have been at once good novelists and good Catholics? The fact is that certain themes cannot be celebrated in words, and tyranny is one of them. No one ever wrote a good book in praise of the Inquisition.

As I have noted at least once before, these lines have aged unusually well. Poetry that requires someone else’s permission to write isn’t poetry worth reading. And more and more, the crowdsourced censorship I see in the creative fields is turning writers, artists and even some academics into glassy-eyed automatons. They are perfectly skilled at writing land acknowledgments, speaking the correct pronouns, and retweeting the right hashtags, but increasingly useless at everything else. In another age, these people might have blamed the government for this. In 2018, on the other hand, they can only blame themselves.