Education

Fear and Self-Censorship in Higher Education

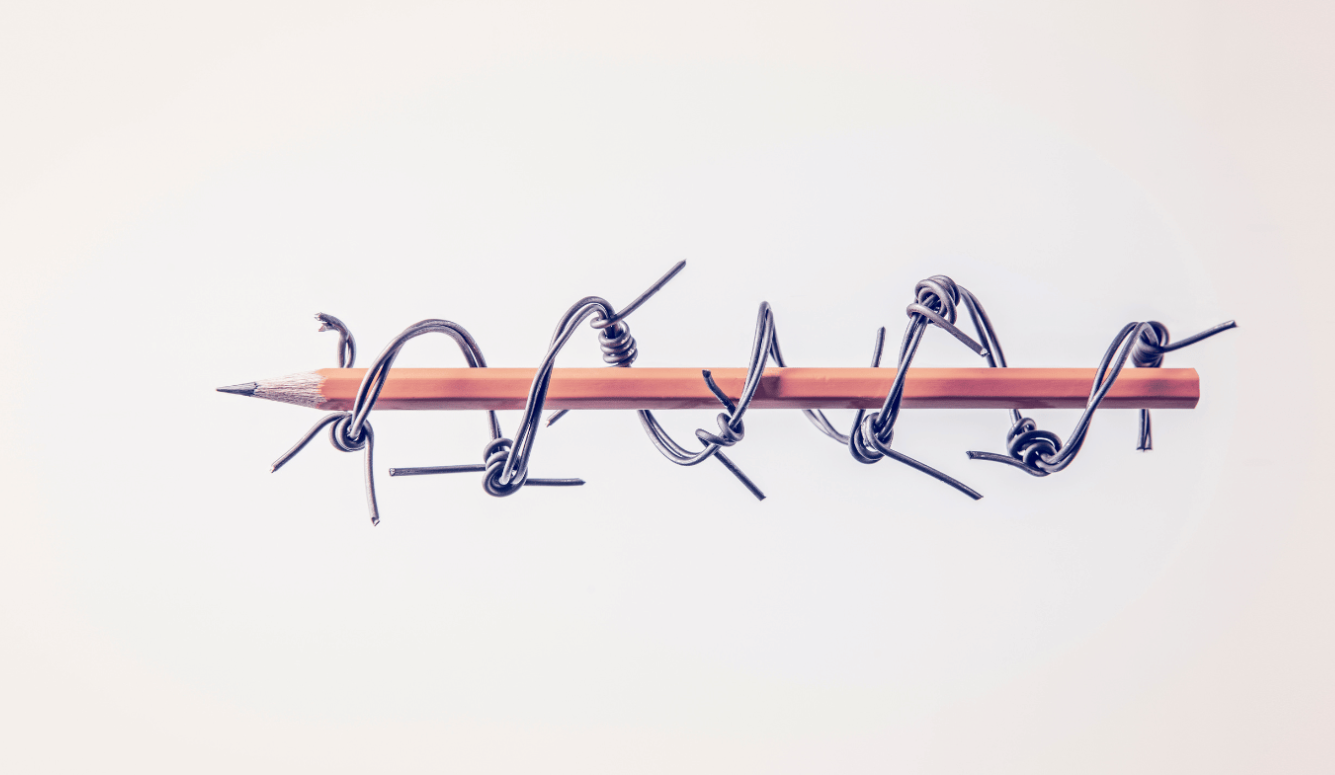

Unless we can conquer our anxiety and restructure the way we interact, dreams of social unification will remain dead on arrival.

Like the rest of my generation, I have been anxious and apprehensive for as long as I can recall. The crippling anxieties of Gen-Z and younger millennials are everywhere apparent; we have a mental-health epidemic with a higher generational suicide risk, which have variously been attributed to awareness of worldly chaos, the COVID-19 pandemic, and chronic onlineness. We have grown up comfortable indoors, isolated with the computer, console, or TV, and reliant upon Instagram and disembodied voices in place of social interaction. We accept one or two posts as “news” and information we see online as “facts,” usually without further research. South Park has remodeled Cartman after the image of the doomscrolling, internally distraught Gen-Zer, and I can’t help but see myself and my peers in him. This generational affliction has hindered our ability to communicate and problem-solve, and the technology upon which we are so hopelessly dependent has only enabled an inflation of animosity and alienation, further aggravating a crisis of hyperpolarization and mental-health issues.

Before going to college, I felt pretty confident in my convictions. In high school, I regularly testified in the Texas State Legislature and Austin City Council, where I spoke about issues including sex trafficking, paid sick leave, and postpartum depression. While I advocated for what I believed in and connected other young people to avenues of democratic participation, I also operated with a level of hostility that neglected community building. At school and in my community, I was known as a social-justice activist, and played the part of self-righteous progressive who some admired and others feared, ready to jump down anyone’s throat at the first hint of an offensive utterance.

This behavior—modeled by other Internet-educated activists—is a product of fear and anxiety, fueled by cultural panic, media narratives, Internet oversocialization, extremist spectacles, and deliberate division. A thoughtful political alternative to anxiety, offering strategic solutions to societal problems, has yet to capture the attention of young progressives en masse, and this has cast aware yet inactive people adrift in the throes of the culture wars and trapped them in a toxic relationship with hyperpolarization and hypervigilance. If it hadn’t been for my bittersweet college experience, I might still be stuck in this dynamic of dichotomous dread, like a hearty portion of my infographic-obsessed generation.

I started at Barnard College of Columbia University in the Fall of 2020. New York City was relatively shut down, classes had been moved to Zoom, and people seemed to be losing their minds. At the beginning of the COVID era, I felt somewhat hopeful when ordinarily apolitical people were inspired to dig into every worldly woe that content creators hyped up. But by May 2020, I realized that this cultural change had merely created an echo chamber fed by unarticulated fears of alienation.

Soon, girls who had made homophobic or antisemitic comments about me in the past were coming out as “nonbinary,” adding they/them, ACAB, BLM, and sometimes a rainbow flag to their social-media bios, and declaring themselves proud converts to digital progressivism. It was performative, theatrical, and intended to show that they were as enlightened as their activist peers. I would be thrilled if I thought people were actually thinking critically and genuinely dedicated to advocacy, but they aren’t. They seek social acceptance, not social change, and this has resulted in bleak and narrow classroom discussions. My old (and now kicked) habit of ideologically charged verbal warfare became an Olympic sport; anyone who smelled blood pole-vaulted down the nearest open esophagus.

I did not share my identity when I introduced myself in class, and this was the beginning of my social downfall. By the second semester, I had already been accused of being “transphobic” and “co-opting the trans experience” after my poetry classmates read pieces I had written about my penis envy and simultaneous phallus phobia. None of my peers asked me how I identified, nor did anyone stop to wonder why I would write about this kind of thing in the first place. In addition to leaving notes on my poem and condemning its “offensiveness” in critique, one student requested that I conference with my professor about my “concerning” material. They denounced my poetry as derogatory (which it wasn’t) when it would have been more appropriate to describe it as vulgar, lowbrow, and just plain bad (which it was).

To my chagrin, my queer peers proved to be among the most unwelcoming and jaded people with whom I interacted while at Columbia. I had foolishly assumed that the compassionate Left would want to include others and welcome dialogue. Thankfully, I found some solace among faculty, who encouraged me to share my ideas and also worried about the dearth of free and productive classroom debate. Throughout my degree track, but especially since COVID, students have remained quiet when encouraged to express divergent or possibly controversial opinions. Most analyze the world through the hyperidentitarian script spoon-fed to us all by social media.

My peers and I were afraid of three things: (1) Looking stupid, (2) offending someone, and (3) social ostracization. For a generation so keen on displaying individualism through gender identity, we are paradoxically terrified of being seen as different. To say that I was depressed about the communal hypervigilance in classrooms would be an understatement; I was catastrophizing about how this culture of self-silencing would impact us in the long run. Thus began a senior thesis investigation which released all the hair-triggers of my classmates—plastic surgery, cancel culture, and the oversocialization of Gen-Z progressives (who fail to embody any kind of “leftism” besides angrily reaffirming the zeitgeist of self-loathing, crippling anxiety, and inaction).

When the day came to present my thesis, I received much anticipated pushback from those I thought would object to my Freud and Houellebecq citations. About half the class freaked out when I said that breast implants can cause cancer and therefore posed a risk to transwomen who seek augmentations for gender affirmative care. They became even angrier when I claimed that the image of women we are affirming is informed by pornography and the male gaze, concerns that preoccupied second-wave feminist activists like Andrea Dworkin.

I was accused of legitimizing the idea of “cancel culture” and was asked to provide examples of people who have lost their livelihoods and wellbeing to cancellation. But as writer Clementine Morrigan has often argued, the people who suffer most from socially enforced censorship are often alienated to begin with. Celebrities are not usually taking life-altering financial hits that will upend their stability, nor do they lose their social networks from saying something objectionable, but ordinary people are less well-protected from caustic harassment campaigns. And while cancel culture may not appear to have material effects for most, its aggressive promotion of oppositional conformity certainly propels radicalism on both sides.

In the 1960s and ’70s, liberals were the free-speech enthusiasts of the United States. Students and activists used the first amendment to protect their vocal opposition to the Vietnam War.

The Warren and Burger eras of the Supreme Court, associated with ending school segregation and instituting Roe v. Wade, ensured free-speech protections by enforcing and protecting the Federal Communications Commission’s Fairness Doctrine, which required that broadcasts give equal coverage to controversial issues. Worried about network monopolies and biased reporting, the Fairness Doctrine meant that if a personal attack was aired, the other side was allotted time to respond. But in 1987, under the Reagan Administration, FCC protections were stripped and inflammatory talk-radio began to flourish. While Republicans claimed a deregulation victory, they simultaneously upended free and fair speech media protections for the country, and helped rear the crisis of hyperpolarization.

Most major news networks are partial, which explains the growing attraction of independent writers on Substack and publications like this one. But faithlessness in media institutions is a net negative for everyone, as it tells the public that there is no stable and trusted source capable of providing a broad overview of the world’s daily events. Though conservatives would like to erase their own history and blame the Left for the current manifestation of hyperpolarization, this systemic phenomenon has been festering for decades. It is fueled by a critical thinking deficit and hyperpartisanship, which in turn sprouts from famished public-education guidelines, outrage-inducing news conglomerates, and the politicians who profit from culture-war content.

Like the modern Left, conservatives are prone to conniptions, and unembarrassed to employ reactionary tactics that violate First Amendment values when it suits them. This can be seen in the recent surge in book bans. Florida’s Governor Ron DeSantis has protested that “book ban” is a misleading term, and that the legislation is intended to shield children from “porn” and material that might induce “anguish.” While the text of the “Stop W.O.K.E. Act” and related legislation does not explicitly state that schools can remove books related to the Holocaust or American history, it does advocate the protection of student sensitivities, which is pretty comical coming from those who say they value “facts over feelings.” Such laws set a precedent that literature related to identity, and material which is subjectively concerning or anxiety-producing, can be taken out of students’ hands.

Before and after Trump, conservative parents have continued to attack the updated versions of Anne Frank’s The Diary of a Young Girl due to the inclusion of “homosexual themes.”

In the 1980s, conservatives inspired by the Moral Majority crusaded to ban The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald and The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck, two classics of the American literary canon, due to their sexual content. A decade before, Slaughterhouse-Five came under fire for its profanity and, you guessed it, sexual content. While this trend of book banning has plagued American politics for some time, its ostensible goal of protecting children from sexually explicit literature and possibly uncomfortable topics is futile when parents, legislators, and kids alike all know that the Internet is swamped with far more graphic material.

Perhaps even more worrying and authoritarian than the book bans is the censuring of Montana’s trans legislator Zooey Zephyr. Zephyr has been barred from House debates for the rest of the 2023 session after she said she “hoped” her fellow lawmakers would “see the blood on [their] hands” after passing restrictions on gender affirmative care.

The Montana House has not allowed the representative to speak for several days now, and many have (rightly) called this silencing undemocratic. Besides the obvious issues with censoring an elected politician, the bill passed by the Montana legislature (and since signed into law by the state’s governor) is poorly written, with nondescript fiscal notes, little to no plan for enforcement, and broad overreaches, bringing state government further into the private lives of Montana’s population. The subjective offensiveness of her remarks does not justify her silencing. This isn’t a partisan phenomenon, but a widespread neurosis that has infected all who fail to filter out the omnipresent fumes of the culture wars.

We seem to be unable to separate neo-Nazis, child predators, serial rapists, and every other image of evil from bad-faith actors and from those who are parsing ideas or sharing their experiences. Attacking our neighbors over objectively minimal differences and tone-deafness only pushes people to the fringes. Detransitioners like Chloe Cole and Prisha Mosley have run into the (temporarily) hospitable arms of Matt Walsh, a deliberately corrosive right-wing pundit at the Daily Wire. The automatic rejection of detransitioners by progressive activists has been a terrible miscalculation. Detransitioners are vulnerable young people in need of support and compassion, but because there is currently no room for heterodox narratives on the Left, detransition advocates have fallen in with anti-trans conservatives with social clout and cash. Alliances with figures like Walsh will only make nuanced dialogue harder, and detransitioners risk becoming pawns of conservatives who support outright bans on gender affirming care, even for adults. The upshot is a political culture that continues to thrive on division and mutual hatred.

Not everyone in my class pole-vaulted down my throat. Some of my peers spoke about their fear of offending their classmates. Most of those who contributed to the discussion (rather than automatically dismissing my thoughts out of hand) were born abroad, came from immigrant families, or didn’t spend all their time on social media. In other words, those who had actually been exposed to different perspectives seemed to be the most openminded. They said that they felt hopeless—they didn’t want to risk saying something inflammatory, nor did they see how people could cooperate to alleviate common suffering in an atmosphere of stress and stratification.

After listening to this, I pointed out that a culture of hypervigilance is counterproductive to the kind of social progress and community-building that leftists claim to value. Dismissing our neighbors as idiots traps us in a dynamic of blaming the individual and pitting ourselves against people instead of the superstructural causes of hardship. And if those who are unproductively critical of Gen-Z can’t see that we’ve been hoodwinked by our elders who created this atmosphere, then efforts to diminish division will be fruitless.

It’s fair to say that I got a taste of my own medicine, but I’m happy to report that for the past three or so years, I’ve mellowed and found people to talk to who are not brainwashed by TikTok algorithms. I am still highly conscious of my words, though I hold back less and give myself grace. But self-silencing will remain a culturally derived trait for Zoomers on the Left who remain painfully conscious of the online panopticon’s power. It is worth knowing one’s audience before speaking, but the widespread stifling of expression—and the concomitant dismissal of the democratic debate, cooperation, and compromise—is dangerous.

Half-baked and unfamiliar ideas can help us to collaborate and to build on one another’s thoughts. Even if something is deemed unnerving or objectionable, isn’t it more productive to debate—to seek and find common ground, to fine-tune theories—than to attack and punish others for differences of opinion and experience? If conversation is avoided or shut down, progress becomes hopeless. If, on the other hand, we are able to discuss and disagree, we can move past fear towards a healthier body politic.

I hope that more young people are becoming aware of the absurdities of the prevailing climate. Some are. But unless we can conquer our anxiety and restructure the way we interact, dreams of social unification will remain dead on arrival. Hyperpolarization precludes coalition building, and I find it hard to understand why so many progressives are unable to grasp this obvious point. We have fallen into the same dynamic as the Right: alienating our own while preaching against alienation, further nourishing the collective crisis of anxiety and depression.