Top Stories

As a Former Dean of Harvard Medical School, I Question Brown’s Failure to Defend Lisa Littman

Pursuing unorthodox scholarship can lead to frustration and failure, to exciting breakthroughs, or anything in between.

This week’s controversy surrounding an academic paper on gender dysphoria published by Brown University assistant professor Lisa Littman—brought on by the post-publication questioning of Dr Littman’s scholarship by both the journal that published it, PLOS One, and Brown’s own School of Public Health—raises serious concerns about the ability of all academics to conduct research on controversial topics.

Gender dysphoria—the clinical term used to describe a condition in which one’s sense of gender identity diverges from one’s biological sex—is an important issue that cries out for more research. In the case of children who assert a transgender identity, clinicians, researchers, school officials and other interested parties face profound, life-altering decisions regarding treatment. As a physician, endocrinologist and medical researcher, I have a professional interest in the topic. But the biology, psychology and treatment of gender dysphoria is not the focus of this article. Rather, I herein consider the reaction to Dr Littman’s survey research, which explored the reportedly growing phenomenon by which clusters of socially connected teenage girls, some beset by autism spectrum disorder and other mental health challenges, suddenly express feelings of gender dysphoria apparently without having experienced these earlier in life, as is more commonly the case. Dr Littman’s preliminary research suggested that this often occurs after heavy exposure to social-media content extoling the benefits of gender transition. Whether the results of this descriptive survey study will be confirmed and extended will require much additional research.

The fact that Brown University deleted its initial promotional reference to Dr Littman’s work from the university’s website—then replaced it with a note explaining how Dr Littman’s work might harm members of the transgender community—presents a cautionary tale.

Increasingly, research on politically charged topics is subject to indiscriminate attack on social media, which in turn can pressure school administrators to subvert established norms regarding the protection of free academic inquiry. What’s needed is a campaign to mobilize the academic community to protect our ability to conduct and communicate such research, whether or not the methods and conclusions provoke controversy or even outrage.

* * *

The right of university faculty to pursue questions that interest them, free from control or harassment, is a core element of academic freedom. How faculty go about accomplishing their chosen research goals is their responsibility. Once chosen, the results are evaluated by others—by funding agencies, peer-reviewed journals, and eventually by those colleagues responsible for decisions on promotion, tenure and institutional resources. But the initial choice of topic and method must remain within the sole discretion of the researching academic.

By exploring controversial topics that challenge prevailing orthodoxies, scientists always have faced professional risks. Pursuing unorthodox scholarship can lead to frustration and failure, to exciting breakthroughs, or anything in between. Research involving humans, in particular, typically is governed by rigorous ethical and operational standards. Nearly all such research requires approval by institutional review boards before being initiated. These boards are charged with protecting the rights of subjects, and determining whether the overall approach has merit and promise. Dr Littman’s study at Brown passed those requirements. Insofar as we know, Dr Littman’s data were properly analyzed. At PLOS One, her findings were subject to peer review, after which her article was revised in response to reviewer comments; then accepted and published, whereupon it entered the public domain. This is how the process is supposed to work.

Many papers face questions after they have been published, which is well and proper: the systematic assessment and scrutiny of published work is a core method by which the scientific community corrects errors, and builds upon imperfect preliminary observations. There is a real problem with a lack of reproducibility of published science in many academic fields. Efforts to understand and respond to this problem are receiving justified attention. But that is not what has happened in regard to Dr Littman, whose critics have not performed any systematic analysis of her findings, but seem principally motivated by ideological opposition to her conclusions.

Avenues for challenging an academic paper include letters to the editor, journal editorials, invited comments, and efforts by others to conduct research in the same area. Aside from this, critics may allege research misconduct in the form of plagiarism, fabrication or falsification. If an informed party credibly asserts one of these three claims in regard to a published article, it is the academic institution’s responsibility to investigate and reach a fair conclusion. The outcome of such inquiries sometimes requires that the paper in question be retracted, or in some way modified—though this typically follows confidential investigations that can take months or even years. Absent evidence of academic misconduct, an institutional inquiry of this sort rarely, if ever, occurs to address the validity of a faculty research paper, in my experience.

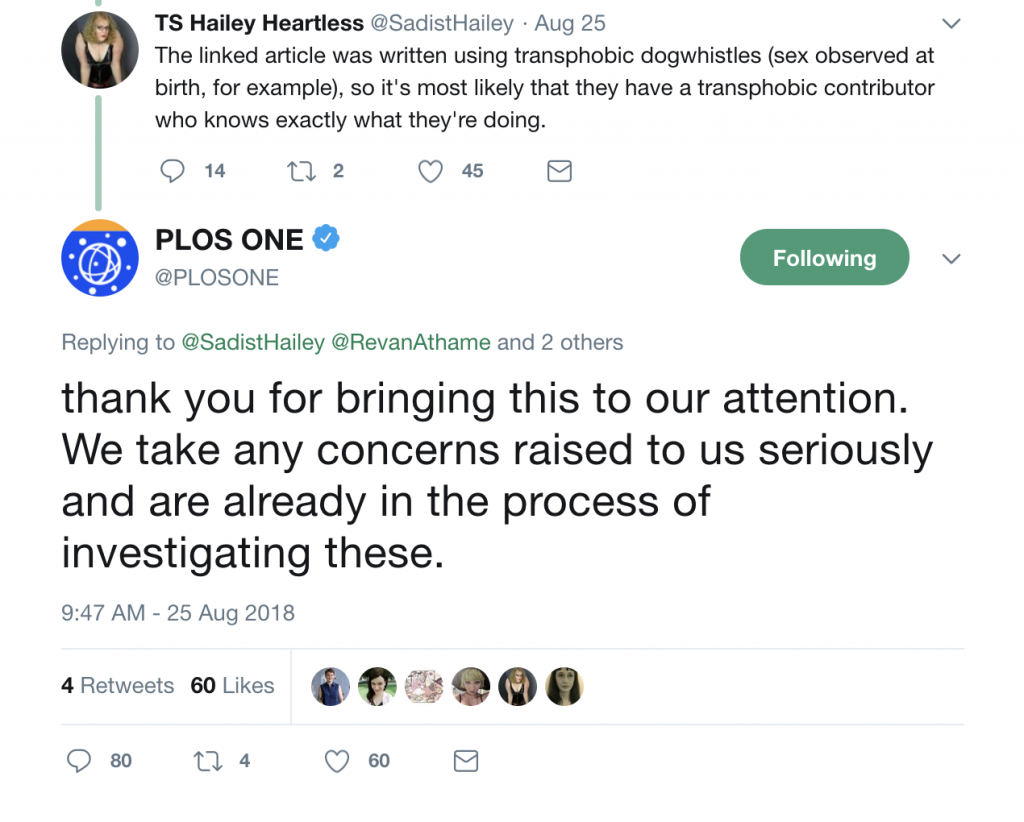

There is no evidence for claims of misconduct in Dr Littman’s case. Rather, unnamed individuals with strong personal interests in the area under study seem to have approached PLOS One with allegations that her methodology and conclusions were faulty. Facing these assertions, which predictably drew support from social media communities populated by lay activists, the journal responded rapidly and publicly with the announcement that it would undertake additional expert review.

In all my years in academia, I have never once seen a comparable reaction from a journal within days of publishing a paper that the journal already had subjected to peer review, accepted and published. One can only assume that the response was in large measure due to the intense lobbying the journal received, and the threat—whether stated or unstated—that more social-media backlash would rain down upon PLOS One if action were not taken.

There were also said to be unidentified voices within the Brown community who expressed “concerns” about the paper. But when Brown responded to these concerns by removing a promotional story about Dr Littman research from the Brown website, a backlash resulted, followed by a web petitionexpressing alarm at the school’s actions. The dean of the School of Public Health, Bess Marcus, eventually issued a public letter explaining why the removal of the article from news distribution was “the most responsible course of action.”

In her letter, Dean Marcus cites fears that “conclusions of the study could be used to discredit the efforts to support transgender youth and invalidate perspectives of members of the transgender community” (my italics). Why the concerns of these unidentified individuals should be accorded weight in the evaluation of an academic work is left unexplained.

The idea that unnamed parties might apply conclusions from a study such as to cause some vaguely defined harm to other third parties is a spurious basis for the university’s actions. Virtually any research finding related to human health may be used for unrelated and inappropriate purposes by independent actors. Indeed, this happens frequently in medical science, as when nutrition research is used to promote diets far beyond the validity of the underlying data. When this occurs, responsibility lies with those committing these acts, not the paper or its author.

The next paragraph of the dean’s letter affirms “the importance of academic freedom and the value of vigorous debate informed by research,” and hails the spirit of free inquiry as “central to academic excellence.” But these high-minded sentiments are then undercut by several qualifications. The dean states that scientific faculty must also “listen to multiple perspectives and recognize and articulate the limitations of their work.” Further, when the research has implications for health of the communities being studied, the researchers have “an added obligation for vigilance in research design.” Such general principles apply equally to any research related to human health. But expressing them in this context implies that Dr Littman is guilty of violating these principles in some specific way—an implicit accusation for which no evidence is evident or adduced.

The next paragraph offers unwavering support for “studying and supporting the health and well-being of sexual and gender minority populations,” as well as “unshakable” support for the “full diversity of gender and sexual identity.” These statements of support are entirely appropriate. But in contrast to the material contained in the prior paragraph on academic freedom and inquiry, there appear in this section no caveats or clarifications. One cannot avoid the conclusion that the author sought to communicate a hierarchy of principles, with diversity on top, academic freedom underneath.

Another key point is notable for its absence: There is no suggestion whatsoever of support for Dr Littman, a faculty member in good standing for whom the personal and professional consequences of these events could be devastating. The dean of a school is in effect the dean of the faculty. While she must exercise balance and objectivity when controversial issues arise, her responsibilities include the expression of appropriate support for a beleaguered faculty member until and unless clear evidence emerges to impugn that scholar’s behavior or work. And yet, Dean Marcus is mute on this subject.

The dean’s letter ends by calling for a future symposium, with a panel of experts who will “present the latest research in this area and…define directions for future work.” Input is sought from “faculty, staff and students about the composition of this panel and scope of the discussion.” While one could imagine such an event theoretically providing an antidote to harassment and political influence, obvious concerns present themselves. These include the apparent implication that the research agenda should be influenced by campus stakeholders who are not experts in this specific area. Indeed, given this week’s spectacle, it might be anticipated that a robust and scientifically rigorous symposium to discuss the issues raised by Dr Littman would be that last thing the dean seeks.

At a time such as this, when a university’s academic mandate is under threat from diverse ideological actors, there is simply no substitute for a strong leader who supports academic freedom and discourse. The dean’s letter raises serious questions about whether the dean of Brown’s School of Public Health is willing to be such a leader.

For centuries, universities struggled to protect the ability of their faculties to conduct research seen as offensive—whether by the church, the state, or other powerful influences. Their success in this regard represents one of the great intellectual triumphs of modern times, one that sits at the foundation of liberal societies. This is why the stakes are high at Brown University. Its leaders must not allow any single politically charged issue—including gender dysphoria—from becoming the thin edge of a wedge that gradually undermines our precious, hard-won academic freedoms.