Art and Culture

The Public Humiliation Diet

In today’s topsy-turvy world, virtue signaling trumps being virtuous.

Reading about James Gunn’s defenestration by Disney for having tweeted some off-color jokes 10 years ago, I was reminded of my own ordeal at the beginning of this year. I’m British, not American, a conservative rather than a liberal, and I didn’t have as far to fall as Gunn. I’m a journalist who helped set up one of England’s first charter schools, which we call ‘free schools,’ and I’ve sat on the board of various not-for-profits, but I’m not the co-creator of Guardians of the Galaxy. In some respects, though, my reversal was even more brutal than Gunn’s because I have spent a large part of the past 10 years doing voluntary work intended to help disadvantaged children. It is one thing to lose a high-paying job because of your ‘offensive attitudes,’ but to be denied further opportunities to do good hits you deep down in your soul. At least Gunn can now engage in charity work to try and redeem himself, as others in his situation have done. I had to give up all the charity work I was doing as a result of the scandal. In the eyes of my critics, I am beyond redemption.

My trial-by-media began shortly after midnight on January 1, when I started trending on Twitter. The cause was a piece about me in the Guardian newspaper which had just gone live. The headline read: “Toby Young to help lead government’s new universities regulator.” That was a bit misleading. I was one of 15 non-executive directors who’d been appointed to the board of the Office for Students, a new higher education regulator, not one of its leaders. The reason was because of the four schools I’ve co-founded and because I’m one of a handful of conservatives involved in public education. Liberals outnumber conservatives on nearly all public bodies in Britain and the Office for Students is no exception. Of the 15 non-executive directors announced on January 1, only three were identifiable as right-of-center, myself included. The chair, Sir Michael Barber, is the former head of research for a left-wing teaching union and spent eight years working for Tony Blair in Downing Street.

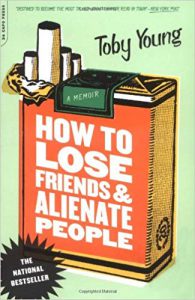

But I’m also a journalist and in the course of my 30-year career I’ve written some pretty sophomoric pieces, many of them for ‘lad mags.’ I spent 48 hours in the Welsh mountains simulating the selection course for the Special Air Service, Britain’s elite special forces unit. I went undercover as a patient at a penis enlargement clinic in London. I even got a professional hair-and-make-up team to transform me into a woman and then embarked on a tour of New York’s gay bars to try and pick up a lipstick lesbian. I wrote a best-selling memoir about these and other misadventures in journalism called How to Lose Friends & Alienate People that was turned into a Hollywood movie starring Simon Pegg. In other words, not your typical appointee to the board of a public regulator.

I’ve also, like James Gunn, made some pretty stupid jokes on social media many moons ago that I wish I could take back. But they’re out there, along with everything else I’ve ever written, and it doesn’t take long to find them. And the reason I was trending on Twitter is because literally thousands of people were Googling me and coming up with reasons why I wasn’t a fit person to be on this board.

I thought the row would blow over within 24 hours, but what began as a Twitter storm turned into a major story (it was a slow news week). Nine days later, when I announced my resignation from the Office for Students, I was leading the BBC news.

How did that happen? Well, it didn’t help that I’m pro-Brexit and was a prominent campaigner for the Leave side in the referendum about Britain’s membership in the European Union. Many distinguished academics thought that alone was enough to disqualify me from regulating Britain’s universities. The British professoriat is passionately pro-EU and believes anyone who doesn’t share their view is a racist bigot.

But the main reason I became such a lightning rod is because I had been appointed by the Prime Minister. If it could be shown that I was an unsuitable person to sit on this board, that would embarrass Theresa May. And boy, did they go at it. Nine days later I had been tarred with all the vices of a privileged white male—tarred and feathered.

The first wave of attacks took the form of dredging up articles I’d written in the past and mining them for evidence that I held unpalatable views. For instance, someone on Twitter dug up a 17-year-old piece I’d written for the Spectator, where I’m an associate editor, headlined: “Confessions of a Porn Addict.”

Notwithstanding the headline, it was actually a fairly serious article defending the British Board of Film Classification’s increasingly liberal attitude towards pornography and pointing out that sexual violence is more prevalent in countries with draconian anti-pornography laws—such as Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Indonesia—than in Holland, Denmark, and Sweden.

In support of the argument that porn doesn’t deprave and corrupt, I referenced the poet Philip Larkin’s fondness for bizarre erotica and cited an incident he relayed in a letter to the novelist Kingsley Amis. The most celebrated English poet of the post-war period was loitering outside a sex shop in London’s red light district, too embarrassed to go in, when suddenly the owner stepped outside.

“Was it bondage, Sir?” he politely inquired.

As a matter of fact it was.

Unfortunately, in the course of relaying this anecdote I described Larkin as a “fellow porn addict.” Hence the headline at the top of the piece.

It was the sub-editor’s idea of a joke—and I thought it was funny too, until the article was cited as evidence that I wasn’t a fit and proper person to serve on a public regulator. It was a good illustration of Kingsley Amis’s rule about self-deprecating remarks: “Memo to writers and others: Never make a joke against yourself that some little bastard can turn into a piece of shit and send your way.”

A couple of hours after it surfaced on Twitter, the London Evening Standard ran a piece headlined: “New Pressure on Theresa May to Sack ‘Porn Addict’ Toby Young from Watchdog Role.”

That was followed up by the Times of London the next day: “‘Porn addict’ Toby Young Fights to Keep Role as Student Watchdog.” The story began: “Fresh pressure to remove Toby Young from a new universities watchdog was heaped on Theresa May yesterday when it was revealed he has admitted to being a porn ‘addict.’”

Note the use of the word “revealed,” as if this unsavory fact had just come to light, rather than been dug up by some online metal-detectorist frantically searching for anything I’d written that could be deemed ‘offensive.’ One of the few people to come to my defense was Fraser Nelson, the editor of the Spectator, who marveled at the prosecutorial zeal of my enemies: “At one stage, the top 10 articles in our online archive (going back to 1828) were all Toby Young’s, as his army of detractors were hard at work.” It goes without saying that no one is actually offended by any of this material, or at least very few people. After all, it would be a bit odd if people spent hours trawling the internet in the hope of finding opinions or jokes that genuinely upset them—and then broadcast them far and wide in the hope of upsetting lots of other people, too. Rather, they’re looking for stuff they can pretend to be shocked by, Captain Renault style.

When Fraser told me about the search activity, I joked that at least a new generation of readers was discovering my work. But, of course, these offense archaeologists are about the least sympathetic readers an author could have. They’re just looking for sentences and phrases they can take out of context to cast you in a bad light. The same technique has been used to shame Kevin Williamson, Bari Weiss, Daniella Greenbaum, Sam Harris, Bret Weinstein, Dave Rubin, Jason Riley, Heather Mac Donald, Jordan Peterson, Charles Murray, and countless others. It’s cherry-picking—or rather, cherry bomb-picking. As Ben Shapiro, another victim of this tactic, wrote recently: “It’s not that these people are hated because they’ve said terrible things. It’s that they’re hated, so the hard Left tries to dig up supposedly terrible things they’ve said.”

The term “offense archaeologists” isn’t mine, by the way. It belongs to Freddie deBoer, the essayist and blogger who wrote a brilliant piece about the toxic effect that this climate of intolerance is having on public discourse. “That’s what liberalism is, now—the search for baddies doing bad things, like little offense archaeologists,” he wrote. I would link to it but he’s deleted it, presumably because some Witchfinder General sniffed it out and started preparing the ducking stool.

The most serious of the charges against me is that I’m a ‘eugenicist.’ That claim was based on an article I’d written for an Australian magazine in which I discussed the possibility that in the future a couple might be able to fertilize a range of embryos in vitro and, after analyzing their DNA, choose to implant the one likely to be the most intelligent. If that ever does become possible, the first people to take advantage of it will be the rich so they can give their children an even bigger head start. In other words, it will make the problem of growing inequality and flat-lining social mobility across the industrialized world even worse.

My solution, as set out in the article, was that this technology, if it comes on stream, should be banned for everyone except the very poor. I wasn’t proposing sterilization or some fiendish form of genetic engineering. Just a type of IVF that would be available for free to the least well off, should they wish to take advantage of it. Not mandatory, just an option.

I called this “progressive eugenics,” which in retrospect was clearly a mistake. It was more like the opposite of eugenics—free IVF for the poor—but few people bothered to read the piece. The fact that I’d used the E word was enough to damn me.

That was exhibit A in the case for the prosecution.

Exhibit B was my attendance at an academic conference at University College London last year at which some of the speakers had a history of putting forward contested theories about the genetic basis of intelligence. My reason for going was because I had been asked—as a journalist who has written about genetics—to give a lecture by the International Society of Intelligence Researchers at the University of Montreal later in the year, and I was planning to talk about the risks of venturing into the nature-nurture debate, particularly if your views run afoul of blank slate orthodoxy. I thought the UCL conference, which was invitation-only, would provide me with some anecdotal material that I could use in Montreal—and it did. I referred to the clandestine gathering in my lecture, comparing these renegade academics to the Czech dissidents who used to meet in Václav Havel’s flat in Prague in the 1970s.1

So, because I discussed a form of embryo selection in an Australian magazine, and because I attended this conference at UCL, I was the Spectator’s answer to Josef Mengele. It doesn’t matter that my father-in-law is Jewish and under the Nuremberg Laws my children would have been murdered because they have a Jewish grandparent. In the eyes of my critics, I was a Nazi.

According to the Green Member of Parliament, Caroline Lucas, my “horrific views on eugenics” rendered me “unfit for public office.” The left-wing journalist Polly Toynbee wrote a column in the Guardian headlined: “With His Views on Eugenics, Why Does Toby Young Still Have a Job in Education?” The Labour politician Dawn Butler, the shadow minister for women and equalities, accused me on Question Time, Britain’s flagship current affairs program, of “talking about eugenics and weeding out disabled people.”

She just made that up, by the way. I have never talked about “weeding out disabled people.” I found that particularly distressing because I have a disabled brother and I am a patron of the residential care home he lives in. I hope he wasn’t watching Question Time that night.

That’s one of the worst aspects of seeing your name dragged through the mud—the fear that people you know and care about are going to believe some of the terrible things people are saying about you and the feeling that there’s nothing you can do about it. You can get out there and defend yourself, of course, but once the calumnies have gathered momentum it’s hard to stop them metastasizing. To paraphrase Mark Twain, a piece of fake news gets all the way round the world and back again and starts trending on social media before the truth has put its boots on. A researcher at MIT recently published a paper in the journal Science showing that the truth takes six times longer, on average, than a lie to be seen by 1,500 people on Twitter.

Another example: an essay I wrote in 1988 about the English class system, which included some unflattering descriptions of socially awkward boys at Oxford, was dredged up as evidence that I was opposed to poor kids going to university. A former BBC journalist and self-professed Marxist accused me on Twitter of “[despising] working class kids who try to make good through education.”

Hard to know where to start with that one. As an Oxford undergraduate, I was part of a widening participation program that involved visiting schools in deprived parts of the country to try and persuade the students to apply to the university. I joined the US-UK Fulbright Commission as a Commissioner in 2014 and have supported the Commission’s work to secure full scholarships at American universities for British students from disadvantaged backgrounds. At the high school I helped set up, four out of every 10 children are from under-privileged backgrounds and our exam results put us in the top 10 percent of all high schools in England. 83 percent of our graduating class this year got college offers, 63 percent from Russell Group universities, Britain’s Ivy League.

How could an essay I wrote 30 years ago—30 years ago—be a legitimate basis on which to judge my attitude towards social mobility and not all the work I’ve done since? As David French wrote in the National Review about Ben Shapiro, we should judge people on the sum total of their work, not some isolated tweet or hot take.

In my case, it was as if observing progressive speech codes when talking about certain groups—such as disadvantaged kids—is more important than actually helping them. In today’s topsy-turvy world, virtue signaling trumps being virtuous.

The allegations continued. Two of the most hurtful ones against me were that I’m a misogynist and a homophobe.

Those claims were based on ill-judged comments I’d made on social media. Like James Gunn, I had deleted them—because they were asinine, ill-conceived attempts to be provocative, usually late at night after several glasses of wine—but the outrage mob thought that made them more indicative of what I’m really like, not less. In their eyes, these were the moments I had let slip the mask of decency and revealed the hideous gargoyle beneath.

Six years ago, I tweeted something about the cleavage of an MP sitting behind the leader of the Labour Party in the House of Commons and three years before that I made some similar observations about several female celebrities, including Padma Lakshmi, the Indian cookbook author whom I used to work with on a food reality show. That was enough to get me labelled a misogynist.

Those tweets were awful and I wish I hadn’t sent them. I’m not convinced that objectifying women is itself a form of harm, but it dehumanizes them, turns them into something ‘other,’ and that can be a way for men to give themselves permission to cause harm. But does sending those tweets make me a misogynist? Someone who hates all women, including my wife who I’ve been happily married to for 17 years and our 14-year-old daughter? That verdict has a horrible finality about it, as if I will forever be defined by a few lapses of judgment and nothing else I have done—could do—will assuage the guilt. To rub the point in, numerous people expressing outrage about this on Twitter added the hashtags #MeToo or #TimesUp, as if I am morally indistinguishable from Harvey Weinstein. For the record, I’ve run several medium-sized organizations in my career and employed hundreds of people and I’ve never been accused of sexual harassment or discrimination or anything remotely like that. On the contrary, I’ve always been supportive of my female colleagues. If you write off all men who’ve engaged in locker-room banter as misogynists, don’t be surprised when that term stops eliciting the moral outrage you expect. It’s the feminist equivalent of playing the race card.

Eight years ago—again on Twitter—I described George Clooney as being “as queer as a coot.” That made me a homophobe. Again, stupid thing to say, but the dictionary definition of a homophobe is “a person with an extreme and irrational aversion to homosexuality and homosexual people.” I wanted to protest that I had taken on Nigel Farage, then the leader of the right-wing United Kingdom Independence Party, in a public debate about gay marriage. That in the secondary school I helped set up I had worked hard to create a welcoming environment for LGBTQ staff and students. That some of my best friends are…

But I knew I’d just be howling into the void. Trial by media is like being in the dock at a Soviet show trial—no due process, no inadmissible evidence. Guilty as charged, next stop social Siberia, as Steven Galloway discovered. But unlike Galloway, who was falsely accused of rape, I was sort of guilty. Whenever I lapse into self-pity in the company of my friends and claim I was the victim of a witch-hunt, they gently point out that I wasn’t entirely innocent. The women accused of being in league with the devil in 17th-century Salem weren’t actually witches, whereas I had written the offending articles and tweets. I was a self-described “porn addict,” even if I hadn’t meant that line to be taken literally.

My counter-argument is that some of those accused of devil worship were, in fact, guilty of other offenses, such as adultery, but that didn’t make them witches. Like deputy governor Thomas Danforth, those sitting in judgement upon me claimed to be able to peer into my soul and see the festering corruption within. I wasn’t just being accused of having thought and said some inappropriate things. Rather, those were evidence of a diseased mind.

My most egregious sin was a tasteless, off-color remark I made while tweeting about a BBC telethon to raise money for starving Africans in 2009. That was reproduced on the front page of the Mail on Sunday, Britain’s second-biggest-selling Sunday newspaper. The headline ran: “PM’s Disgust at Student Tsar’s Sordid Tweets.” I’d now been promoted from “helping to lead” the new universities regulator to “student tsar” in order to fuel the outrage machine.

At this point, the cry for my scalp had reached fever pitch. An online petition calling for me to be sacked from the Office for Students had attracted 220,000 signatures. My daughter was refusing to go to school. My wife said that if one more person came up to her and said “Are you okay?” she was going to hit them. I felt I had no choice but to issue a public apology and stand down.

In one respect, that was a mistake. I had been warned that abasing yourself at the feet of the outrage mob and apologizing would just embolden them. They will take it as a blanket admission of guilt and demand that you be removed from all your remaining positions until you’ve lost your livelihood—and so it proved to be.

In the weeks that followed I was forced to resign from the Fulbright Commission, stripped of my Honorary Fellowship by Buckingham University, and I had to give up my nine-to-five job as head of an education charity—the one that paid the mortgage and enabled me to put food on the table and clothe my children.

But I don’t regret apologizing, not entirely, because it was heartfelt. When I saw my puerile tweet on the front page of the Mail on Sunday I was filled with a burning, all-consuming sense of shame. I wanted to crawl into a cupboard and hide. My first thought was: “Thank God my father’s not still alive.”

My dad, Michael Young, was involved in education too. He helped set up the Open University, Europe’s largest higher education institution, and was elevated to the House of Lords by James Callaghan, a Labour Prime Minister. Several pieces appeared after I resigned saying I had disgraced his name, including one by a journalist who’d known my father and whom I’ve always liked and respected. This same man had written a relatively sympathetic profile of me for the Guardian seven years earlier. That’s one of the most disheartening things about being shunned and cast out by your colleagues—the people you hoped would stick up for you join the lynch mob along with everyone else. It was as if he was taking me aside into a dark room, handing me a glass of whisky and a revolver and telling me to do the decent thing.

Being publicly shamed is a brutal, shocking experience that strips you of your dignity and I’ll always look back on it as one of the low points of my life. But, thankfully, my thoughts never turned to suicide. Others haven’t been so fortunate. Earlier this year, Jill Messick, a Hollywood producer, became the subject of an online witch-hunt when she was falsely accused by Rose McGowan of covering up for Harvey Weinstein. She decided not to challenge McGowan’s account because she didn’t want to make it harder for other victims of sexual harassment to come forward. But the gap between the person she knew herself to be and the anti-feminist villain she was being portrayed as on social media became too much and on February 7 she took her own life.

It’s that gap that causes the pain. Quinn Norton, who was hired and then fired by the New York Times in the space of eight hours following an online mobbing earlier this year, wrote a good article for The Atlantic about her ordeal. She said her detractors created a “bizarro-world” version of her, an online doppelgänger. It was the usual show trial in which people dug up things she’d said on social media in the distant past, deliberately turned a deaf ear to nuance, irony, and context, and transformed her into a pantomime villain. You know in your heart of hearts that that’s not who you are, but the willingness of others to believe the worst can lead to self-doubt. If so many people think I’m a bad person, maybe I really am.

This is a form of cognitive dissonance, I think. Surveying the burning wreck of my career, I was initially consumed by a terrible sense of injustice. Why me? What have I done to deserve this? I hadn’t realized it before my life unraveled, but I had been laboring under the illusion that we live in a fair universe—the just world fallacy. I thought that if I was, on balance, a good person, the universe would somehow take that into account when deciding my fate. I’m not religious—I don’t even believe in karma. At least, I didn’t think I did until events conspired to make it crystal clear that karma is a big fat stinking lie. Then, to my astonishment, I found myself in a state of shock. It’s all so unfair! But like many people whose worldview is upended by reality, instead of abandoning my just world hypothesis, I doubled down on it. Not consciously, but semi-consciously—involuntarily. Cognitive dissonance. So I began to think, “Maybe I deserve all this public ignominy and shame.”

That triggered a few depressive episodes, but what saved me from spiraling down into the full-blown, clinical depression that often follows an experience like this was exercise. During those nine days in January when I became the most reviled man in Britain I lost half a stone (seven pounds). I joked to my wife that I was on “the public humiliation diet.” Like many middle-aged men, I’ve often dreamed about losing weight and getting into shape, but haven’t had the time to do anything about it. Now, unexpectedly, I did. I decided to bank that half a stone, lose some more weight and do some exercise—finally get rid of that spare tire. So I’ve been doing 15 minutes of high intensity interval training (HIIT) every day, often followed by five minutes of stomach crunches, then a run or a swim. I’m now two stone lighter than I was on January 1 and, while I can’t claim to have a six pack, I do have the faint outline of one. (I can see it, even if my kids fall about with laughter whenever I tense my stomach muscles and say, “Look, look!”)

It’s been wonderfully therapeutic. In part, that’s because it has enabled me to regain control over some small aspect of my life. Okay, I may not be able to battle the outrage mob and my enemies may have succeeded in destroying my career and ruining my reputation, but, hey, at least I can control my own body weight! Small potatoes in the grand scheme of things, but it means I don’t feel like a complete victim.

Then there’s the self-flagellatory dimension. Exercising hard, particularly HIIT, hurts. (The clue is in the name.) The part of me that blames myself for what’s happened, and thinks I deserved everything I got, gets a lot of satisfaction from punishing the miscreant responsible. I’ve become a hair shirt conservative.

Finally, there’s the serotonin. After I’d suffered my reversal of fortune I sought consolation in Jordan Peterson’s 12 Rules For Life, but it had the opposite effect. I read the infamous chapter about lobsters and discovered that crustaceans who’ve been bested in a fight suffer from reduced levels of serotonin and as a result become “a defeated looking, scrunched up, inhibited, drooping, skulking sort of lobster, very likely to hang around street corners and vanish at the first sign of trouble.” As with lobsters, so with humans, Peterson argues, which immediately made me think that I was going to start behaving like a pathetic loser in the lobster dominance hierarchy. But, thankfully, I didn’t. And the reason, I think, is because of the exercise, which boosts serotonin. My sudden, vertiginous loss of status—like something out of a Tom Wolfe novel—undoubtedly depleted my serotonin levels. But the daily, intense physical exercise seems to have made up for it. This lobster will live to fight another day.

Six months have passed since I experienced my time in the stocks and I’m still trying to process what happened (as you can probably tell). I keep circling back to the same question: Why were some people prepared to cast judgment based on such meager evidence? Why did certain words I’d used in the past count for so much more than my actions?

I think the answer must have something to do with the rise of identity politics. In the Oppression Olympics, I’m not about to win any medals. As a white, heterosexual, cis-gendered male, I’m an apex predator in the identitarian food chain and, as such, responsible for all the injustices suffered by the oppressed, including historic injustices dating back hundreds of years—colonialism, slavery, sexual exploitation, you name it.

That’s the context in which I was labelled a “homophobe” and a “misogynist,” not to mention a “porn addict,” a “eugenicist,” and someone who “despises working class students.” As far as the hashtag activists are concerned, all white, heterosexual, cis-gendered males are guilty of those sins—and that goes double for Brexit-supporting, middle-aged Tories. They assume we must hold all these toxic beliefs because how else could we justify the ‘structural inequality’ that preserves our privileged status? It simply doesn’t occur to them that there’s an intellectually respectable case for free-market capitalism, or that there could be a moral basis for opposing end-state equality—100 million plus killed by communism, etc.—or that those of us who don’t share their philosophy are equally concerned about justice. The conservative tradition is entirely unknown to them.

Even if your social media history is squeaky clean, you’re going to have difficulty persuading the intersectional Left that you have a useful role to play in public life if you tick all the wrong demographic boxes, as I do. The best thing you can do is ‘check your privilege’ and stand aside. This is how Suzanna Danuta Walters, professor of sociology and director of the Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Program at Northeastern University, put it in a recent comment piece for the Washington Post titled, “Why can’t we hate men?“:

So men, if you really are #WithUs and would like us to not hate you for all the millennia of woe you have produced and benefited from, start with this… Don’t run for office. Don’t be in charge of anything. Step away from the power. We got this. And please know that your crocodile tears won’t be wiped away by us anymore. We have every right to hate you. You have done us wrong.

Maybe I’m kidding myself. After all, some of the other people appointed to the board of the new regulator were men—even white, heteronormative men—and no one objected to them. But it was a disheartening episode for someone who’s been involved in politics all his life and was looking forward to contributing more. As a non-executive director of the Office for Students, I was hoping to address some of the problems afflicting Britain’s universities—soaring tuition fees, grade inflation, the growing intolerance for unorthodox ideas—by sitting round the table with people of different views and having a lively debate. The person who replaced me is a liberal, which means the number of ‘out’ conservatives on the 15-person board has been reduced to two. As Jonathan Haidt has pointed out many times, our society prizes every kind of diversity except the one that matters most of all—viewpoint diversity. We’re not going to come up with democratic, workable solutions to difficult problems if we stay within our echo chambers and refuse to engage seriously with our opponents.

Which is why it pains me to see fellow conservatives mimicking the mobbing tactics of the identitarian Left, whether it’s going after Al Franken, Joy Reid, or James Gunn. We should not embrace the witch-hunter’s credo that says people are defined by their worst moments, that if you’ve said something crass or insensitive about a victim group, particularly if you’re ‘privileged’, then you suffer from a form of original sin so deeply imprinted on your soul that no amount of good works can expunge it. The outrage mob seem to be in thrall to a particularly unforgiving religious cult. Nietzsche said that the West’s tragedy in the 20th-century was that we would be afflicted by the same puritanical abhorrence of out-group behavior as our Christian forebears, but because we could no longer bring ourselves to believe in God there would be no way to save these malefactors—guilt without the possibility of redemption. Good theory, wrong century.

Will I get a second chance?

I’m still writing for the Spectator, which has never wavered in its support, doing some editing for Quillette (thanks Claire!), and working on a book about the neo-Marxist, postmodernist Left. None of this pays the mortgage, but it keeps me busy. My wife Caroline, a lawyer who gave up her job to care for our children, has re-entered the work force, so our household income should recover.

In March, I stepped down from the board of the charity I co-founded that looks after my schools—the fifth position I’ve had to give up since my public shaming. That was the biggest blow of all. I’ve written an international best-seller, starred in a one-man show in London’s West End, and co-produced a Hollywood movie. But getting involved in education and trying to give others the opportunities I’ve had is easily the most rewarding thing I’ve ever done. I hope that one day, when this period of liberal McCarthyism has passed, I’ll be allowed to resume that work.

1 A flippant analogy, perhaps, given that the speakers at the conference weren’t risking imprisonment for their unorthodox and—in some cases—inflammatory views. Nevertheless, the fact remains that many honest scientists, like Charles Murray and Linda Gottfredson, are routinely defamed as ‘white nationalists’ by the ostensibly respectable Southern Poverty Law Centre and the perfectly legitimate study of individual and group differences has become highly dangerous to a person’s livelihood and reputation. This ought to worry anyone concerned about academic freedom and the right of behavioural scientists to carry out research.