Top Stories

Bridging the STEM Gender Gap Divide

When the story broke that that Dr. Summers had attributed the STEM gender gap to a lack of aptitude on the part of women, What was he thinking?

Another still small voice has joined the chorus of those calling for us to reconsider our approach to the gender gap in technology. Writing in Quillette, University of Washington computer science lecturer Stuart Reges discussed in depth why there is reason to believe that the tendency of more men than women to pursue careers in the field may arise primarily from innate factors rather than bias or discrimination.1 Predictably, many have called for him to lose his job as punishment for speaking this heresy.2 However, one response that stood out from the others was written under the intriguing and provocative title “Women in tech: we’re training men to resent us” by Microsoft software engineer Kasey Champion.3 In it, she describes how learning that the article had been written by Mr. Reges, who had been her teacher and mentor when she was a student at the University of Washington, challenged her to rethink her view of men who think differently on these issues. She goes on to discuss his arguments in detail, explaining what she believes he got wrong and right. Since she seems to be genuinely interested in dialogue, I write this response as a step toward establishing a serious, respectful exchange of ideas on this important issue.

https://t.co/LD9AqOJp1l

— infinitesimal (@infinitesimal_p) July 2, 2018

Very measured response to Stuart Reges' article on @QuilletteM by @techie4good. I disagree with a few minor points, but very good article in general.

Our Industry’s Messaging Toward Women

Ms. Champion describes her initial reaction to seeing the article as follows:

Yes, that article is about me [her emphasis]. It’s about women I call colleagues, friends, students, family. The author, Stuart Reges, is the head lecturer for the University of Washington’s introductory programming program. The program that is the foundation of my entire career. Not only was Stuart one of my first cs [sic] teachers, but he hired me into my first management position, and this year helped hire me to teach at my alma mater.

Before I was even able to open the article I was practically hysterical. What if I open this and it turns out my secret teenage fears were true all along? That the man who took a chance on me when no one else would thinks I’m not qualified to do the thing I love to do.

This description of the emotional reaction that the article provoked is revealing but not surprising to those of us who have followed this issue closely. Indeed, it is illustrative of one of the greatest flaws in the messaging of the women in science movement, through which it has let women down.

Essentially, the message that the movement has sent to young women goes something like this: Women are just as good at computer science and software engineering as men. Therefore, your work is valued. The field may be male-dominated for now, but we’re working to change that, and you can be part of that change. The future is 50/50—we’ll make sure of that, so there will come a day where you’ll be welcome wherever you go.

There’s just one problem with this message: What if the future isn’t 50/50? Are we teaching women to pin their hopes, their ability to feel that they and their work are valued, on an event that may or may not actually happen? Are we teaching them to assume that those who see things differently take these positions out of hostility toward them? If so, are these approaches helpful?

This concern is not unique to gender. In his book The Blank Slate, the psychologist Steven Pinker addresses the innate differences that exist between people in a broader sense, debunking the notion that no such differences exist.4 He directly addresses the political concerns that have made it appealing for so many people to deny their existence:

[T]he doctrine of the Blank Slate, which had been blurred with ideals of equality and progress for much of the century, was beginning to show cracks. As the new sciences of human nature began to flourish, it was becoming clear that thinking is a physical process, that people are not psychological clones, that the sexes differ above the neck as well as below it, that the human brain was not exempt from the process of evolution, and that people in all cultures share mental traits that might be illuminated by new ideas in evolutionary biology.

These developments presented intellectuals with a choice. Cooler heads could have explained that the discoveries were irrelevant to the political ideals of equal opportunity and equal rights, which are moral doctrines on how we ought to treat people rather than scientific hypotheses about what people are like. Certainly it is wrong to enslave, oppress, discriminate against, or kill people regardless of any foreseeable datum or theory that a sane scientist would offer.

Following the wisdom of Professor Pinker, we might instead wish to deliver the following message to young women—and young men—considering a career in technology: Your work is valued. It doesn’t matter whether you’re male or female, what the color of your skin is, or whether you’re in the majority or minority. The only thing that you should be judged on in this profession is the quality of your work. No discovery in genetics or neuroscience is ever going to change that. Even if it turns out that fewer people of your demographic turn out to be interested and/or talented in this field, that doesn’t matter. If you as an individual are equally interested and talented, then we value you equally and want you to succeed and feel welcome here.

Wouldn’t this message be far more liberating and empowering? By decoupling our values from facts of biology that are beyond human control, we make unconditional our message of welcome to all those who have the interest and talent and wish to join us in developing the technology of the future.

The Errors of James Damore

Ms. Champion describes the responses to Mr. Damore’s document as falling into one of two categories, characterizing him as either an “EVIL, IGNORANT, RACIST, SEXIST IDIOT” or a “PERFECT ANGEL MARTYR” (her capitalization). While I don’t believe that I have characterized Mr. Damore as either perfect or an angel, I won’t deny that my prior writing on his case has focused almost exclusively on the ways in which he has been mistreated. I chose this focus because I believe that the mistreatment that he endured was a grave injustice and that all other issues in his case paled in comparison. That said, in the spirit of finding common ground, I will now offer two ways in which I believe that he was mistaken. I do not view these mistakes as moral failings and offer them not to join in the demonization of Mr. Damore but rather as constructive criticism that will hopefully be useful to all involved in moving forward toward a more constructive dialogue.

When I first read the document, my gut reaction was twofold. On the one hand, I was relieved to see that these ideas were finally getting a public hearing. For far too long, virtually all discussion in major media towed the politically correct line that the gender gap was the result of some sort of discrimination, whether past or present, overt or implicit. In the rare case where this narrative was challenged, the challenge came from extremists who discussed the issue in needlessly inflammatory ways. For example, Milo Yiannopoulos reported on an experiment that failed to find gender bias against women in software engineering interviews with the incendiary headline, “There’s No Hiring Bias Against Women In Tech, They Just Suck At Interviews.”5 This sort of rhetoric is counterproductive. It only served to cast a cloud of illegitimacy over perfect valid research that should have been a wake-up call to reconsider widely held assumptions. By compiling the relevant research and presenting it in a manner that was scientifically rigorous and devoid of anything that could honestly be classified as hate speech, Mr. Damore performed a much-needed public service.

However, I knew that, despite its scientific validity, the document in its present form was unlikely to persuade anyone who wasn’t already at the very least skeptical of the politically correct narrative. Given the degree to which emotions ran high around this issue, simply presenting the factual evidence could be perceived as hostile. In order to reach those who might feel threatened by the possibility of innate differences, Mr. Damore would have needed to start out by first explaining why the existence of innate differences should not pose a threat to women in technology before delving into the evidence—something along the lines of the passage from Dr. Pinker quoted above. Ideally, this reassurance would have been reiterated throughout the document. I am under no illusion that approaching it this way would have protected Mr. Damore from having his career attacked, but it certainly could have increased the number of people who would have been sympathetic to him to at least some degree.

Mr. Damore’s second error, one made by many people on both sides of this divide, was to treat the causes of the gender gaps “in tech and leadership” as being one and the same.6 Not all men are the same, just as not all women are the same. The fact that software engineering and corporate executive positions tend to draw from the male population does not mean that they draw from the same subset of that population. We often hear about the need for more flexible work environments to accommodate the primary responsibility for child-rearing that many women take on.[7] The software companies where I have worked have had 40-hour work weeks, flexible hours, work-from-home options, and generous parental leave benefits. Yet, their staffs have remained overwhelmingly male. Other professions such as medicine and law tend to be far less flexible, yet they have approximate gender parity. Therefore, this is unlikely to be a major factor behind the gender gap in software engineering, although it could contribute to the gender gap in executive positions, which tend to be very demanding in terms of working hours. On the other hand, the impersonal and objective nature of writing code could make such an activity appeal to predominantly men. This would not apply, however, to executive positions, which tend to involve far more interpersonal activities such as negotiations.

Mistaking Boggarts for Death Eaters

Ms. Champion makes an allusion to the Boggart, a magical creature that appears in J.K. Rowling’s novel Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, as a metaphor for men who question the prevailing narrative.8 The Boggart takes the form of whatever most frightens the person who confronts it. However, when a witch or wizard learns to conquer their fears, they can force the Boggart to transform into something comical that no longer poses a threat and thereby destroy it. She describes her mental model of Mr. Reges as being a Boggart, first appearing threatening but then ceasing to pose any threat once she found the courage to read the article and come to understand what he actually believed.

This story reminds of an experience that I had more than a decade earlier surrounding a similar controversy in 2005 involving the then-president of Harvard University, Larry Summers. When the story broke that that Dr. Summers had attributed the STEM gender gap to a lack of aptitude on the part of women, I was puzzled. What was he thinking? Wasn’t he accusing certain people of being incapable of doing something that they had been doing for decades? It wasn’t until two years later than I finally read his speech in full and came to understand that what he had actually said was far different from what I had believed he had said.9 Dr. Summers was speaking solely in statistical terms. He was not calling for discrimination or accusing any woman of lacking aptitude simply by virtue of being a woman. Rather, he was saying that the small percentage of the population with the highest levels of aptitude in science might contain more men than women. He raised this not as the sole cause of the gender gap but rather as one of three and not the most important. I realized that I had been part of the problem. It was because of the rush to judgement without knowing all of the facts made by people like me that he had lost his job. From then on, I resolved to never judge a person guilty of racism or sexism based on portrayals in the media without first reading what they said, verbatim and in context.

The Boggart metaphor also applies is a second way that Ms. Champion may not have realized. In addition to distorting one’s perceptions, assuming the worst of others can literally cause them to become more extreme. When someone is demonized, they will often develop an animus toward the person or people demonizing them. When someone is silenced, they will feel forced to retreat to their own echo chamber, only able to speak their mind to those who largely think the same things as them. In cases where someone is misguided or mistaken, their views might be changed or refined as a result of dialogue. Yet, those same views will only become more extreme if forced into an echo chamber. This phenomenon is by no means exclusive to this one issue. There is every reason to believe that it played a role in the election of Donald Trump. For years, rural and working-class white Americans were struggling. If they dared to suggest their grievances should be heard on equal footing with those of women and minorities, they were condescendingly dismissed as “privileged” by the Democrats, while the Republicans remained silent for fear of being branded racist or sexist if they spoke out. Is it any wonder that many of these people flocked to a candidate who made it clear that he felt their pain when no one else in a position of power would? Had those in power treated all Americans with respect, it is conceivable that the Trump candidacy would have never even picked up steam.

If Ms. Champion continues to engage with those of us on the other side of this divide, I suspect that she will find far more Boggarts than Death Eaters. While the forced silence has prevented me from being able to identify colleagues at my company who share my views, I have been able to meet such people in other contexts, especially at moderate-, conservative-, and libertarian-leaning political groups. While I have found others who believe that innate differences play a role in causing the STEM gender gap, the number of people I have met who believe that women who work in technology shouldn’t be there, that a woman’s contribution to the field is worth less than that of a man, or that women should be subject to discrimination is exactly zero. In fact, when one reads the writings of Mr. Damore and Dr. Summers, it becomes clear that there is no reason to believe that either of them believes any of these things and every reason to believe that they don’t. Those who have felt threatened by one or both of them would do well to reconsider whether these perceptions are accurate.

Other Forms of Diversity

Ms. Champion criticizes Mr. Reges for associating diversity solely with gender. I agree with this criticism but believe that it would be better directed at diversity efforts in the technology industry as a whole rather than at one particular individual. In my experience, our industry has become so obsessed with its gender ratio that such concerns seem to trump anything and everything else. Even race has become an afterthought. I recently attended a conference where the code of conduct included an anti-harassment statement in which race and religion appeared at the end of the list of protected classes, after such things as “physical appearance” and “body size.”10 To the extent that ordering matters, it would seem that these should appear at or near the front of the list, in light of the bloody history of slavery, lynching, religious wars, pogroms, and genocide that has taken place.

A related criticism that should be made of the way that we talk about our industry is that we focus solely on the types of diversity that are lacking and say nothing of the diversity that does exist. The sole metric that we use for diversity in the industry is the percentage of the big three “underrepresented” demographics: African-Americans, Hispanics, and women. Little attention is given to the fact that there is an abundance of other minorities, including immigrants, Jews, Muslims, atheists, Asians, LGBT, and people on the autism spectrum. My first mentor in computer science was a woman who immigrated from Bulgaria. The first team on which I worked coming of school consisted of five engineers who were from five different countries on four continents. My current team includes not just Americans but also Koreans, Indians, and a Pakistani. We have several LGBT team members, and I am on the autism spectrum. I’ve always felt that one of the coolest things about working in our profession is that it gives us the opportunity to meet brilliant people from different cultures all around the world. Simplistically casting the industry as an “old boys’ club” or the last bastion of the WASP patriarchy seems woefully out of touch with what it is actually like.

Are Women Happy Here?

Mr. Reges claims that most of the women in technology who he knows are happy working in the industry, while Ms. Champion disagrees. My own experience is at least somewhat more similar to that of Ms. Champion in that many of the women whom I know have at one point or another expressed dissatisfaction with the state of gender diversity in the industry. The catch is that a dissatisfaction, even a very strong one, with certain aspects of one’s job may not necessarily translate into an overall dislike of the job as a whole. Therefore, it is conceivable that both Ms. Champion and Mr. Reges are correct at the same time, that many women are dissatisfied with the state of gender diversity while simultaneously being satisfied with most other aspects of their work. This type of sentiment can exist on both side of the gender gap divide. I would assign a high overall satisfaction rating to the industry as a whole because of the many things that it does right despite being deeply frustrated with the degree to which our leaders are willing to censor and discriminate in the name of promoting diversity.

It is also worth considering exactly what grievances women have been expressing about life as a software engineer. Those that I have heard from women I know have either amounted to a desire to see the gender ratio change or involved relatively trivial microaggressions. For example, one of my female colleagues once recounted an anecdote of being told by a Brazilian engineer that she met at a conference that she was the first woman he had ever met who worked in security. I have never heard any personal accounts of my female colleagues enduring discrimination or bona fide sexual harassment. It speaks volumes that the bulk of the anecdotes that I have heard related took place not in the offices where the women worked on a daily basis but rather at conferences, often international conferences that included attendees from countries that may have very different norms from our own concerning the relationship between the sexes.

Is Computer Science Dry?

Ms. Champion dismisses Mr. Reges’s contention that women simply choose other fields because that it where their passion lies on the grounds that “the traditional way of teaching Computer Science makes it hard for students to see it as anything other than a dry, laborious vehicle to building operating systems or video games.” The problem with this characterization is that “dry” is a relative, subjective term. Many of us have a great appreciation for the ingenuity of an efficient algorithm to solve a difficult problem or the elegance of how programming languages use algebra and object-oriented design to model the operations to be executed and entities to be manipulated by the computer. Research has shown that women are more likely to gravitate toward work involving people, while men—and autistic people—are more likely to gravitate toward work involving things and abstract entities.11 Is it any wonder that we see things differently?

One of my greatest beefs with the messaging of outreach programs directed toward women is that they often tend to misrepresent what life as a software engineer is like, portraying our work as more interdisciplinary and interpersonal than it actually is. In effect, we lure women into the profession by lying to them about what their life will be like here. This could explain at least some of the so-called leaky pipeline where women are more likely than men to leave the profession. After spending some time working in the industry, they discover that what they are getting is different from what they were sold and choose to look elsewhere for work that is a better match for their interests. I saw this recently with one of my colleagues, who left her job for a completely different type of work, one in which she would be paid a fraction of what she earned as an engineer. Her reasons for leaving had nothing to do with gender. She was just interested in doing something different.

If we are serious about supporting women, then that should mean honoring their right to make their own decisions about what career path is right for them and supporting them in their choices. It should not consist of aggressively steering them toward a field in which they are “underrepresented” just because a more even gender ratio looks good for technology companies.

Yet, suppose that Ms. Champion were to be correct on this point: that changing our approach to computer science education would increase the number of women majoring in the field and that we were able to find software engineering jobs matching their interests that would retain them in the profession. That would still leave the problem of the engineers who do work in the “dry” areas of computer science, as these areas are not superfluous but rather crucial. These types of software—compilers and operating systems, web servers and databases—form the infrastructure of information technology without which more applied types of software engineering would be all but impossible. There is every reason to believe that the companies that focus of these types of work would remain predominantly male. The men who work at these companies should be appreciated for their valuable contributions, not loathed on the presumption that they must be creating a hostile environment if few women share their interests and wish to join them. Either way, the public and the media will need to understand that a large gender gap is not necessarily indicative of a workplace that is unfriendly to women. Otherwise, innocent men will continue to be demonized.

Equality vs. Equity

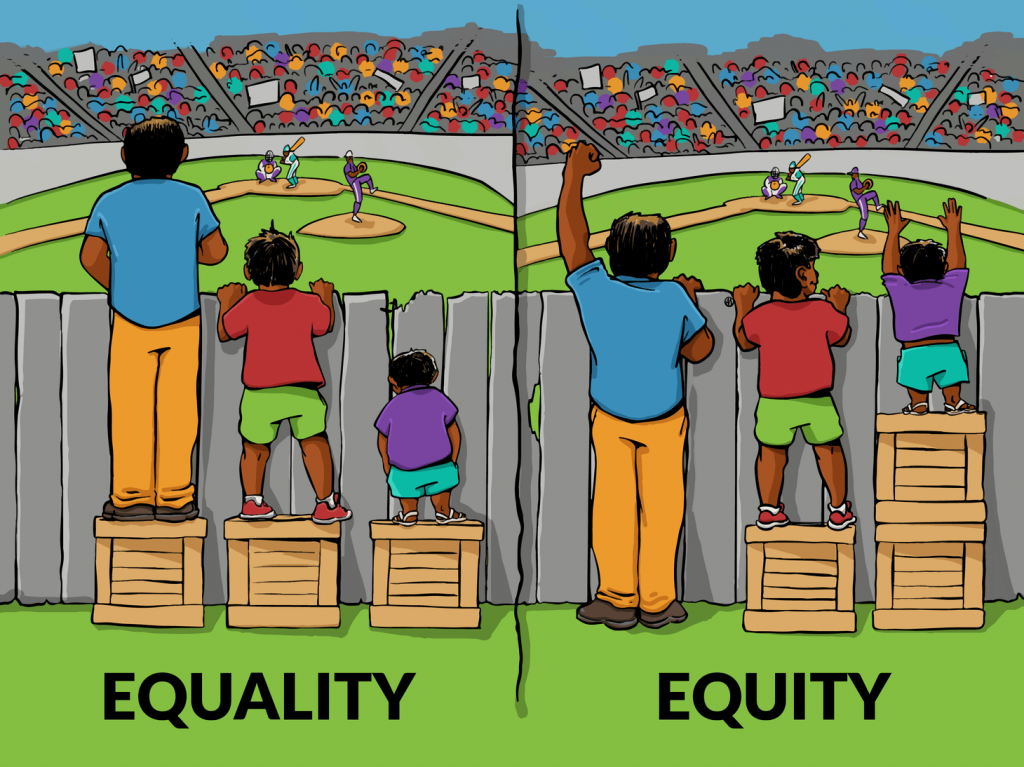

The crux of Ms. Champion’s argument is a response to Mr. Reges’s distinction between equality, meaning equality of opportunity, and equity, meaning equality of outcomes. Mr. Reges believes, as do I, that we should work to ensure that all individuals have the same opportunities to pursue the path of their choice, allow them to make their own decisions as to their majors and career goals, and let the cards fall where they will when it comes to the demographic statistics. Ms. Champion illustrates her initial understanding of what Mr. Reges means with a picture of three people standing on identical stools to see over a high wall. Since they are of different heights, only one can actually see. Unfair, indeed. She then illustrates an alternative in which each person is standing on a stool of a different size so that their heads are at the same level, concluding that this is what both of them with to achieve.

If so, then what is the difference between equality and equity? Those of us who support equality of opportunity wish to ensure that all individuals have the right to choose what resources are right for them. Stools of different sizes are available, and we each pick the one that enables us to see. Approaches of this sort have been used in reality, for example, to accommodate those who are left-handed. We make left-handed desks and scissors as well as right-handed ones and allow people to choose which is right for them. If a right-handed person decides for some reason that a left-handed desk is more useful to them, no one is denying them the right to use one.

Similar approaches could be used to address some of the difficulties faced by people on the autism spectrum. One of the traits that is part of autism is that many of us perceive our senses differently from the way that neurotypical people do. Stimuli that others would barely notice may be perceived by us as unpleasant or even painful, while we may simultaneously be able to tolerate stimuli that others would find aversive. The exact nature of these differences in sensitivity is unique for every autistic person. In my case, I find the sensation of a tie or collared shirt around my neck to be excruciating. Strict formal dress codes have the effect of de facto excluding people with sensitivities such as mine. The solution to this problem is simple: Make these dress codes more flexible or eliminate them altogether. There is no need to grant special privileges on account of an autism diagnosis when no harm is done by extending the same rights to everyone. Taking this approach is to the benefit of everyone, including the autistic person. It avoids giving our neurotypical counterparts reason to feel that they have been the victims of reverse discrimination and hence possibly come to resent us.

In practice, the policies favored by equity proponents are not about allowing individuals to choose what is right for them but rather about empowering authority figures to decide who does or doesn’t deserve support, often based solely on coarse categories such as race and gender. When affirmative action is practiced in college admissions or hiring, a well-qualified white or Asian male applicant can be passed over in favor of a less-qualified female or minority applicant. The right of the individual to be judged solely on merit and not subject to discrimination on account of accidents of birth is subordinated to the right of the group to not be “underrepresented.” At my high school, an African-American woman was granted admission to Princeton while several white and Asian students with higher grades, more advanced coursework, and SAT scores that were several hundred points higher were rejected.

The example of people of different heights receiving stools of different sizes is oversimplified in that it looks at a disadvantage that is objective and easily measured and quantified. Many of the disadvantages used to justify diversity initiatives are difficult if not impossible to measure objectively on an individual level. While they may correlate with race and gender, they vary hugely from individual to individual depending on a whole host of factors such as where one lives and who one’s parents, teachers, and mentors are. It has often been claimed that girls do not receive the same encouragement to go into STEM as boys. Even if this is true (which I strongly question in this day and age), those generalizations do not hold for all boys and all girls. As I discussed in an interview with Quillette that was published earlier this year, encouragement was something of which I received very little growing up.12 I learned programming out of books beginning at age 7, despite having no formalized mentorship until late high school. My parents did not support these activities, and I was bullied mercilessly by my peers for having different interests from what was considered to be cool.

Social justice activists often speak of the value of lived experiences, yet the lived experience of someone like me is clearly unwelcome. If I should have the audacity to suggest that what I’ve endured is of comparable (or perhaps even greater) severity than many of issues raised by the women in science movement, I’ll be at best condescendingly told that I need to check my privilege. As a college student, I watched one of my female colleagues receive a $10,000 scholarship from Google.13 Her qualifications were not even close to mine. She took no initiative to learn any computer science until she was in college. When we were in class together, she would regularly complain about how hard our programming assignments were while I received perfect scores on them. Yet, I was not allowed to even apply because of my Y chromosome. Is it any wonder that many of us feel that we our talent and hard work are devalued by the women in science movement when we are literally paid zero cents on a woman’s dollar?

Intersectionality is in theory supposed to be about the ways in which the treatment of different identities combines in complex ways to produce the experiences that individuals have. Yet in practice, it grossly oversimplifies by failing to take into account the ways in which the disadvantages created in the name of achieving diversity can combine with other disadvantages. Consider the case of a student whose parents are wealthy enough to cover their child’s college tuition but for whatever reason refuse to do so. Perhaps they are selfish and decide to spend the money on a yacht for themselves. Perhaps they reject their child’s sexual orientation or gender identity and have disowned the child. Such a child is caught between a rock and a hard place, disqualified from need-based financial aid yet receiving no family support. In such a situation, a white male is the last thing one would want to be, as such an identity disqualifies the child from a large number of scholarship opportunities no matter how talented or hard-working he may be.

Is the Women In Science Movement Anti-Male?

The final point made by Mr. Reges to which Ms. Champion responds is the concern “that lack of progress will make us more likely to switch from positive messages about women succeeding in tech to negative stories about men behaving badly in tech, which [he thinks] will do more harm than good.” She makes clear that she had not thought of this possibility before and finds it to be “goddamn terrifying,” going on to come to realizations about how her own movement’s messaging may be perceived by some of her male colleagues:

Is this what men have been thinking when we force them to sit in silent agreement? Do men in our industry feel that we view them as personally responsible for the inequalities we are trying to fix? No wonder they resent us!

She goes on to explicitly state that she does not view individual men as responsible for the issues that she is trying to address. This is a huge step forward for which she should be commended.

However, it is worth dissecting in detail exactly what messaging has caused this perception. Actions speak louder than words, and when we are subject to affirmative action policies that deny us the right to be judged solely on our merits without regard to our gender or race, it can easily create the perception that our accomplishments are viewed as having been handed to us on a silver plate through “patriarchy” or “white privilege,” rather than earned through hard work. This perception is only heightened when those who oppose these policies are presumed to be racist and/or sexist and even threatened with our jobs if we speak our minds.

That said, there has been no shortage of hostile words, both within the industry itself and in the media’s coverage of this issue. Screenshots shown in Mr. Damore’s lawsuit revealed ongoing overt hostility toward white men and conservatives among employees at Google.14 While what has happened at Google appears to be more extreme and pervasive than what I have experienced, there have been similar incidents at the companies where I have worked. Media coverage of the sexual harassment found at Uber has portrayed this type of behavior as typical of the industry, when there is every reason to believe that most software companies are far more like Google than Uber.15 When a female engineer who left GitHub accused the company of sexism, the media took her allegations at face value without any evidence.[16] An engineer attending the programming conference PyCon was fired from his job without due process after a female attendee accused him of using technical jargon as sexual innuendo.[17] No evidence was provided beyond her word.

This perception is strengthened by the rise in the broader culture of a radical feminism that has no qualms about displaying hostility toward men and boys. Words such as “mansplaining” and “manologue” serve to denigrate men’s opinions on the basis of our gender and delegitimize our right to think for ourselves if that leads us to see things differently from a woman. Even the phrase “Not all men are like that” has been viewed by many as hate speech.18 For those who don’t see why this is a big deal, consider the following thought experiment. Suppose that instead of blanket statements about men in the context of violence against women, it was blanket statements about Muslims in the context of terrorism. When some Muslims pointed out that “Not all Muslims are like that” and that it is a small percentage who commit acts of terror, they were accused of changing the topic. Enough Muslims do these things that all Jews and Christians have to live in fear. Therefore, the only appropriate response is to join in the outrage without qualification. To raise concerns about the civil rights of Muslims is to lack sympathy for the victims of September 11. It’s funny how, when the demographic being targeted is changed, the arguments of certain feminists become indistinguishable from those of Donald Trump.

A Safe Space for Men, Too?

Ms. Champion concludes her article by making an outreach to men who feel that their views have been censored, offering to be a “safe space” in which “otherwise outlawed ideas” can be discussed. For this as well, she deserves to be commended. However, for men with views that go against the grain to feel safe, she will need to go a step further. Conspicuously missing from her article is any admission that the firing of Mr. Damore was wrong or any condemnation of the appalling—and, dare I say, flagrantly unconstitutional—decision of the National Labor Relations Board to rule that his discussion of scientific research, the conclusions of which some women found offensive, was a form of sexual harassment.19 As long as these types of policies continue to be in place, many of us will not feel comfortable coming forward in the workplace.

I agree with Ms. Champion that safety is not about “the exclusion of tough conversations.” What it is about is the ability to know that we will not be fired from our jobs, blacklisted from the industry, and deprived of our livelihood if what is in our hearts becomes known. As long as the leadership is content to use economic force to silence those who disagree with them with the acquiescence if not outright encouragement of the women in science movement, we will not feel safe.

A tolerant workplace is what we should all be aiming for, and tolerance does not require that we all agree. People of differing opinions should be able to coexist and work together toward a common goal of building technology. Whether or not we see things the same way politically, with respect to the STEM gender gap or any other issue, we should be able to recognize the value that each of us provides to the team. In the long run, science and history will determine who is right and who is wrong on this issue. Yet whatever the answer turns out to be, we should understand that it should never be seen to negate the value that any engineer, whether male or female, brings to the table.

References:

1 Reges, Stuart. Why Women Don’t Code [Internet]. Sydney: Quillette; 2018 Jun 19 [cited 2018 Jul 7]. Available from: https://quillette.com/2018/06/19/why-women-dont-code/

2 Jaschik, Scott. Furor on Women’s Choices Create Gender Gap in Comp Sci [Internet]. Washington (DC): Inside Higher Ed; 2018 Jun 25 [cited 2018 Jul 7]. Available from: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2018/06/25/lecturers-explanation-gender-gap-computer-science-it-reflect-womens-choices

3 Champion, Kasey. Women in tech: we’re training men to resent us [Internet]. [place unknown]: Noteworthy – The Journal Blog; 2018 Jun 22 [cited 2018 Jul 7]. Available from: https://blog.usejournal.com/women-in-tech-were-training-men-to-hate-us-cd3e81c6b15b

4 Pinker, Steven. The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature. New York: Penguin Books; 2002. 509 p.

5 Yiannopoulos, Milo. There’s No Hiring Bias Against Women In Tech, They Just Suck At Interviews [Internet]. London: Breitbart; 2016 Jul 1 [cited 2018 Jul 7]. Available from: https://www.breitbart.com/milo/2016/07/01/not-sexism-women-just-suck-interviews/

6 Davis, Sean. Read The Google Diversity Memo That Everyone Is Freaking Out About [Internet]. Alexandria (VA): The Federalist; 2017 Aug 8 [cited 2018 Jul 7]. Available from: http://thefederalist.com/2017/08/08/read-the-google-diversity-memo-that-that-everyone-is-freaking-out-about/

7 Bravo, Lauren. Flexible working: the secret to professional women’s success [Internet]. London: The Guardian; 2016 Apr 28 [cited 2018 Jul 7]. Available from: https://www.theguardian.com/women-in-leadership/2016/apr/28/flexible-working-secret-women-success-pay-gap

8 Rowling, J.K. Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. New York: Scholastic; 1999. 448 p.

9 Summers, Lawrence H. Remarks at NBER Conference on Diversifying the Science & Engineering Workforce [Internet]. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University; 2005 Jan 14 [cited 2018 Jul 7]. Available from: https://www.harvard.edu/president/speeches/summers_2005/nber.php

10 MongoDB World Code of Conduct [Internet]. New York: MongoDB; [cited 2018 Jul 7]. Available from: https://www.mongodb.com/mongodb-world-code-conduct

11 Sommers, Christina Hoff. The Science on Women and Science. Washington (DC): The AEI Press; 2009. 330 p.

12 Lehmann, Claire. The Empathy Gap in Tech: Interview with a Software Engineer [Internet]. Sydney: Quillette; 2018 Jan 5 [cited 2018 Jul 7]. Available from: https://quillette.com/2018/01/05/empathy-gap-tech-interview-software-engineer/

13 Scholars Program [Internet]. [place unknown]: Women Techmakers; [cited 2018 Jul 7]. Available from: https://www.womentechmakers.com/scholars

14 Scopes, Gideon. Lawsuit Exposes Internet Giant’s Internal Culture of Intolerance [Internet]. Sydney: Quillette; 2018 Feb 1 [cited 2018 Jul 7]. Available from: https://quillette.com/2018/02/01/lawsuit-exposes-internet-giants-internal-culture-intolerance/

15 Kircher, Madison Malone. Gender Discrimination at Uber Is a Reminder of How Hard Women Have to Fight to Be Believed [Internet]. New York: New York; 2017 Feb 21 [cited 2018 Jul 7]. Available from: http://nymag.com/selectall/2017/02/susan-fowler-alleges-sexual-discrimination-against-uber.html

16 Romano, Aji. Sexist culture and harassment drives GitHub’s first female developer to quit [Internet]. Austin (TX): The Daily Dot; 2014 Mar 15 [cited 2018 Jul 7]. Available from: https://www.dailydot.com/debug/julie-ann-horvath-quits-github-sexism-harassment/

17 Brodkin, Jon. How “dongle” jokes got two people fired—and led to DDoS attacks [Internet]. Boston (MA): Ars Technica; 2013 Mar 21 [cited 2018 Jul 7]. Available from: https://arstechnica.com/tech-policy/2013/03/how-dongle-jokes-got-two-people-fired-and-led-to-ddos-attacks/

18 Plait, Phil. Not all men: How discussing women’s issues gets derailed [Internet]. New York: Slate; 2014 May 27 [cited 2018 Jul 7]. Available from: http://www.slate.com/blogs/bad_astronomy/2014/05/27/not_all_men_how_discussing_women_s_issues_gets_derailed.html

19 Mulvaney, Erin. Read the NLRB Memo Defending Google’s Firing of James Damore [Internet]. New York: The Recoder; 2018 Feb 16 [cited 2018 Jul 7]. Available from: https://www.law.com/therecorder/2018/02/16/read-the-nlrb-memo-defending-googles-firing-of-james-damore/