Top Stories

Who's Afraid of Tribalism?

Common fear of ‘tribalism’ reveals them to be members of a particular kind of ‘tribe,’ one that perpetuates its power by accusing opponents of tribalism.

It is not news to anyone that the United States is being torn apart by tribalism. Media commentators widely agree that American politics and society is increasingly polarized—divided into two mutually hostile camps which share ever-fewer references and values. While observers may assign a greater share of blame to the identity politics of the Left or the Right, they are nearly unanimous in their insistence that tribalism now characterizes both sides of the political spectrum.

It may seem obvious that tribalism is a threat to American democracy. But when Andrew Sullivan, Thomas Friedman, and David Brooks agree on something, it should arouse suspicion. These three brought us the Iraq War. With different emphases, they embody the common sense of the political center. They imagine themselves as untainted by the prejudices of partisan tribalism; daring thinkers who defy the taboos of Right and Left alike.

But their common fear of ‘tribalism’ reveals them to be members of a particular kind of ‘tribe,’ one that perpetuates its power by accusing opponents of tribalism. Tracing the history of ‘tribalism’ from its origins in the nineteenth century to its central place in today’s headlines reveals how powerful insiders have sought to delegitimize their opponents by presenting them as irrational primitives.

Inventing Tribalism: Africans and Jews

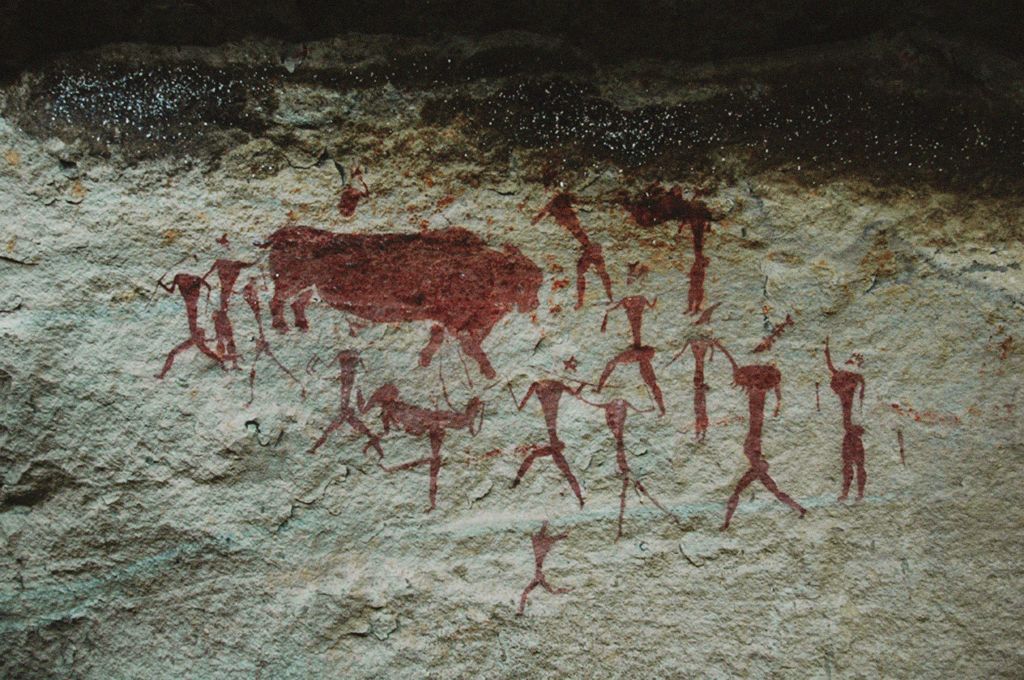

As European empires colonized Africa in the last decades of the nineteenth century, explorers and administrators moved into the continent’s unfamiliar interior. They searched for words to make sense of the bewildering array of societies that they encountered. Many of them turned to ‘tribe.’ The word ‘tribe’ had long been used to describe everything from the Sioux on the North American plains to the ancient Germanic and Turkic peoples who had invaded the Roman Empire. It connoted a small, self-contained population whose distinct cultural norms distinguished it sharply from outsiders—a supposedly primitive form of social life that had been replaced elsewhere in the world by larger structures (states, empires) and identities (nations, races, religions).

Colonial officials tended to describe all African groups as tribes, whether they were speaking of small nomadic populations with only a few dozen people, or of sizeable ethnic and linguistic formations that included millions of people, including those living in urban centers and centralized states. They generally believed that their task—the White Man’s Burden in Africa—was to ensure Africans’ transition to modernity and away from ‘tribalism.’ They understood such diverse phenomena as competition among African groups for resources, resistance to the demands of the colonial state, and demands for greater autonomy as expressions of a singular, atavistic ‘tribalism,’ the virulence of which proved Africans were not yet ready to govern themselves.

As ‘tribalism’ became part of colonial ideology in Africa, it also became a key element of political conversations about another supposedly backward and problematic group: the Jews. Beginning in the late nineteenth century, European and North American observers increasingly criticized Jews and Judaism for being ‘tribal.’ Such views were by no means expressed only by what we might now call the nationalist and antisemitic political ‘Right’; they were also common in progressive circles. Many liberal Christians, who argued that the Bible should be read, not as the literal revelation of God, but as a historical record of the emergence of moral principles, hitched their arguments to a view of Old Testament Judaism as a backward ‘tribalism.’

From this perspective, the advent of Christianity had overcome the spiritual chauvinism of the Old Testament and its Chosen People, transforming Jews who remained unconverted into living anachronisms. As Goldwin Smith—one of Victorian Britain’s leading antisemites—put it in an 1878 essay entitled Can Jews be Patriots? “Christianity offers without tribalism…everything that is universal and permanent” in the Hebrew Bible. Smith linked this theological argument to a political one, when he claimed that Jews living as minorities in Christian countries could never become patriotic citizens. Having refused to give up their spiritual particularism for Christianity, they would similarly refuse to become British, French, etc.

These arguments echoed earlier generations of antisemitic discourse. The philosophes of the eighteenth century French Enlightenment debated what should be done with the “obstinate Hebrews” who seemed equally resistant to religious conversion and cultural assimilation. The German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer contemptuously described Jews as a winkelvolk—a people living in a corner, withdrawn from the world. What changed in the late nineteenth century was not the underlying logic of antisemitism, which blamed Jews for continuing to be Jews, but rather the inflections of its discourse. Now, through the concept of ‘tribe,’ Jews could be rhetorically linked to other populations whose determination to remain themselves troubled Europeans’ sense of superiority.

‘Tribalism,’ by the turn of the twentieth century, was not so much a concept as a slur. To describe a group as ‘tribal’ was to link it to an ancient past of small, ethnocentric peoples, who were destined to give way to larger, more inclusive, and more rational social structures. It was, indeed, to summon the group so described to disappear, to dissolve itself and join the ‘universal’ identities offered by Christianity and European empires. That colonized Africans and Jews living in the West should resist this summons and attempt to retain elements of their ‘tribal’ identities was seen as proof of their intellectual inferiority or moral perversity.

Accusations of tribalism portrayed Africans and Jews as a conservative, particularist ‘other,’ in contrast to the progressive, universalist self of the accuser—whose own in-group chauvinism was thereby occluded. Those who accused others of tribalism could imagine themselves as enlightened individuals who were attempting to share their expansive and unprejudiced worldview, bringing benighted, isolated tribes into the circle of common humanity. Thus defined, ‘tribalism’ could become a perfect weapon not only for imperialists and antisemites, but also for liberal internationalists.

Liberalism Against Tribalism

In the aftermath of World War One, as the possibility of another global conflict and the rise of fascism alarmed liberal observers, they appropriated the language of ‘tribalism’ for themselves. Many progressive academics of the 1920s and ’30s blamed the outbreak of the Great War on European nationalism, which they saw as a disturbing resurgence of tribalism. Just as it had been the cause of the war, so too was nationalist ‘tribalism’ the greatest threat to the post-1918 peace. In 1934, shortly after the Nazis’ seizure of power in Germany, eminent British historian Arnold Toynbee warned of a new war sparked by nationalism, explaining that “the spirit of nationality is a sour ferment…in the old bottles of tribalism.”

This outlook, which promoted the era’s endless peace conferences and the toothless League of Nations as vehicles for transcending outdated nationalism, can be said to have contributed to making another war inevitable. Describing Europe’s belligerent patriotisms and bloody geopolitics as the return of ancient, irrational demons meant ignoring what made them modern and explicable. Was it, after all, an outdated tribalism that made French political figures as diverse as the monarchist antisemite Charles Maurras and the Jewish socialist Léon Blum seek rearmament in the face of a rising Germany? After Toynbee met privately with Adolf Hitler in 1936, he reported that Nazi foreign policy did not pose such a grave threat as he had thought. Imagining that the Third Reich was merely a throwback to past ‘tribalisms,’ he could not perceive Hitler’s distinctly modern ambitions to transform the world.

Having done little to prevent World War Two, or even to understand its coming, the liberalist vision of tribalism not only survived the war, but became a key part of the post-war intellectual consensus. The most important contributor to the liberal appropriation of ‘tribalism’ was the philosopher Karl Popper. Friedman, Sullivan, and Brooks’s fretful columns in today’s newspapers are descendants of Popper’s 1945 opus, The Open Society and its Enemies. Drawing on liberal critiques of ‘tribalism’ in the interwar period and refining them into a forceful (and tendentious) historical and sociological vision, Popper completed the transformation of the term from a weapon of the West’s old colonial order into a weapon of its new regime.

Popper’s two-volume work began with a reading of ancient Greek history that traced how ‘tribes’ gradually formed city-states. In Athens, this transition went further, creating an unprecedented ‘open society.’ Here, for the first time in human history, people recognized each other as individuals, who had the right and capacity to question social norms through the free exercize of their reason. While all previous modes of social organization had been ‘closed societies’ focused on the reproduction of traditional norms and the maintenance of barriers between the community and outsiders, there now emerged a society ‘open’ both to new ideas and to new people. The cosmopolitan, tolerant, and rational society of Athens, however, succumbed to foreign enemies and internal dissenters, who longed for the security of tradition. Its legacy was revived by Enlightenment-era liberals, only to be met, almost immediately, by ‘tribalist’ resistance in the form of nationalism.

Except for the first scene of his historical panorama, when he speaks of proto-state social groups in ancient Greece, Popper’s ‘tribalism’ does not refer to any concrete social fact with identifiable features. Rather, ‘tribalism’ is a permanent feature of human psychology. It is a deeply-rooted “desire to be relieved from individual responsibility.” It is the coward and the weakling’s way of refusing the hard work of rationally examining social norms, a plea to be rescued from the anxiety of thinking for oneself.

The rhetoric of ‘tribalism’ in Popper’s Open Society functions much the same as it had in the writings of colonialists and antisemites. Those who resist the open society—like Africans resisting European imperialism, or Jews refusing to convert to Christianity—are tribalists. They represent both humanity’s backward past and the base instincts repressed by civilized people. They are afraid of novelty, of having to critically examine their traditions, of putting aside their limited, bigoted identities for the true individuality that comes with adopting universal norms. They are, most alarmingly, intolerant, and thus a threat to the tolerant, open society that they refuse to join. The latter must defend itself against them.

Tribalism Today

In the years after World War Two, Popper’s understanding of tribalism influenced many other thinkers, particularly right-wing defenders of laissez-faire capitalism, who imagined themselves as rational individuals upholding universal norms against atavistic forces unreason. Friedrich Hayek pitted free-market liberalism against tribalism. Ayn Rand, expressing Popper’s views in her own breathless style, wrote that “tribalism is a product of fear, and fear is the dominant emotion of any person, culture or society that rejects man’s power of survival: reason.” Tribalism assumed forms as varied as fascism, socialism, and the gay rights movement, but it invariably (inexplicably, wickedly) rejected Rand’s ideals, which, she insisted, were nothing but human nature codified.

The end of the Cold War and the apparent triumph of liberal democratic capitalism brought the Popperian language of ‘tribalism’ into the mainstream of political commentary. Once the initial euphoria of 1989 wore off, observers wondered why some groups in the world continued to resist the West’s hegemony. Benjamin Barber, in his 1996 Jihad vs McWorld: How Globalism and Tribalism are Reshaping the World, classified phenomena as varied as nationalist movements in the former Yugoslavia and the rise of Islamic fundamentalism as expressions of ‘tribalism,’ a perspective shared by analysts baffled by the resurgence of nationalism and the spread of Islamic terrorism.

Islamic groups seeking to reinstall a caliphate are hardly ‘tribal’; they aspire precisely to a form of universal dominion that would undo the current global order. Nor are modern nationalist movements ‘tribal’ in the sense of being based on autochthonous populations that seek to preserve their traditions from change and foreigners. The identitarian right in Europe and the alt-right in North America, for example, are creating transnational coalitions that challenge forms of identity based on national belonging (as Americans, French, etc.) making appeals to racial identity (whiteness) and to Western civilization: rhetorical strategies that transcend borders. These are not exactly the forms of modern internationalism that liberals were dreaming of, but they are modern and international just the same.

Calling such movements ‘tribalist’ provided no analytical insight. It did, however, provide moral authority to the liberal world order, by casting its most powerful opponents as throwbacks to the past. With the collapse of the Soviet Union and Marxist parties throughout the West, class fell behind other categories like religion and ethnicity as an organizing principle of oppositional political movements. By interpreting this shift as a revival of primitive, instinctual tribalism, liberal observers can imagine that nationalist and Islamic fundamentalists, however threatening, do not represent a real alternative to the ‘end of the history.’ They are merely flashbacks, ghosts, indigestion—passing symptoms of irrational resistance to the enlightened center.

The dangers of political polarization are real and obvious. They are particularly so to the journalists and opinion-makers who have made careers appealing to a vanishing liberal consensus. But there are also dangers to their panic about ‘tribalism.’ The troubled history of the word shows us that ‘tribalism’ is analytically vacant and likely to guide policy astray. Sermons against ‘tribalism’ did little to stop World War Two, and indeed gave Hitler time to prepare Germany for a new round of armed conflict.

Besides being simply mistaken, charges of ‘tribalism’ do a moral wrong to those they target. The latter are made out to represent a backward, irrelevant form of existence, while their accusers seem to hold down the citadel of reason and progress. But since the nineteenth century, those accused of tribalism have often been guilty only of trying to remain themselves, of resisting the encroaches of more powerful empires and ideologies, of persevering in being. Others described as tribalist, like Hitler and ISIS, of course, have sought to transform the world and wrest power from the global order imagined as oppressing their people. But there is precisely little that is ‘tribal’ in such ambitions. What is tribal—narrow-minded, hopelessly obsolete, and serving the interests of a clique—is the Washington establishment’s discourse of ‘tribalism.’