Art and Culture

Glamourising the 'Childfree Life' Ignores Reality for Most Childless Women

But the truth is, these women are not 'free' of the children they yearn for. Motherhood is a burden that we would give anything to bear.

Twenty-five years ago, I made the decision to marry the man I love. I was 23 when I packed up my life in Montreal and moved to New York City for him. I had yet to actually meet this man, but as I drove down the I-87 to my new home, I was confident that I was headed exactly where I always expected to be: in love, married, and a mother. And on my first job interview in New York City, I even inquired about maternity benefits. After all, I was expecting twin girls.

To clarify, I wasn’t pregnant. But since I was 10-years-old, I imagined that one day, I’d have twin girls – despite no familial history of twins.

But as the years in New York went by and I remained single, I eventually let go of that dream. I didn’t care if I had three boys. I just wanted to be a mother.

Ultimately, I let go of that dream, too. I’m now 49, still single, and on the other side of hope for motherhood.

I’ve been in love. I believe in love. I’ve loved men who didn’t love me back. I’ve loved men who weren’t ready to love me—or anyone. I’ve met men whom I wanted to love, hoping so deeply to fall over the edge into love with them that it ached. But in the end, I found myself single and unwilling, unable, to settle.

Over time, I’d lie in bed, wondering where that man I moved to New York City to meet and marry was. And where were my babies? Those lonely nights spun into a dizzying cycle of hope and doubt and grief and around again. But it was a grief I learned to keep to myself.

My Circumstantial Infertility—the term I would later create to describe the pain and grief over remaining childless when one does not have a partner — often went unacknowledged, as if my pain was invalid because I wasn’t married. Only married couples dealing with infertility seemed due the pain of their childlessness.

In 2008, as I reached my late thirties, I shifted my career to focus on my cohort, the rising demographic of childless women and discovered how large and undervalued this cohort is. There has been a steep rise in childless women from 1976, when the U.S. Census first began recording fertility rates. Then, 35 percent of women of fertile age were childless. Today, that number is 49 percent.

Still, it’s often assumed that all adult women are mothers, as if we’ve inverted the “W” for woman to the “M” for mother. And while the majority of women do eventually give birth, it’s later than ever. For the first time, more than half (54%) of American women aged 25-29 are childless, as are nearly a third (31%) of women aged 30 to 34. By the end of our fertile years, about one sixth of women (17%) are childless.

Survey data indicates that this group is likely to want to have children in the context of marriage, or at least long-term co-habitation. And when they do finally have children at late-fertile age, they are likely to bear more children than the average mother.

According to Gladys Martinez, author of the 2012 National Health Statistics Report Fertility of Men and Women Aged 15-44 Years in the United States: National Survey of Family Growth,” 80 percent of unmarried women are childless, and of those, 81 percent plan or hope to have children one day.

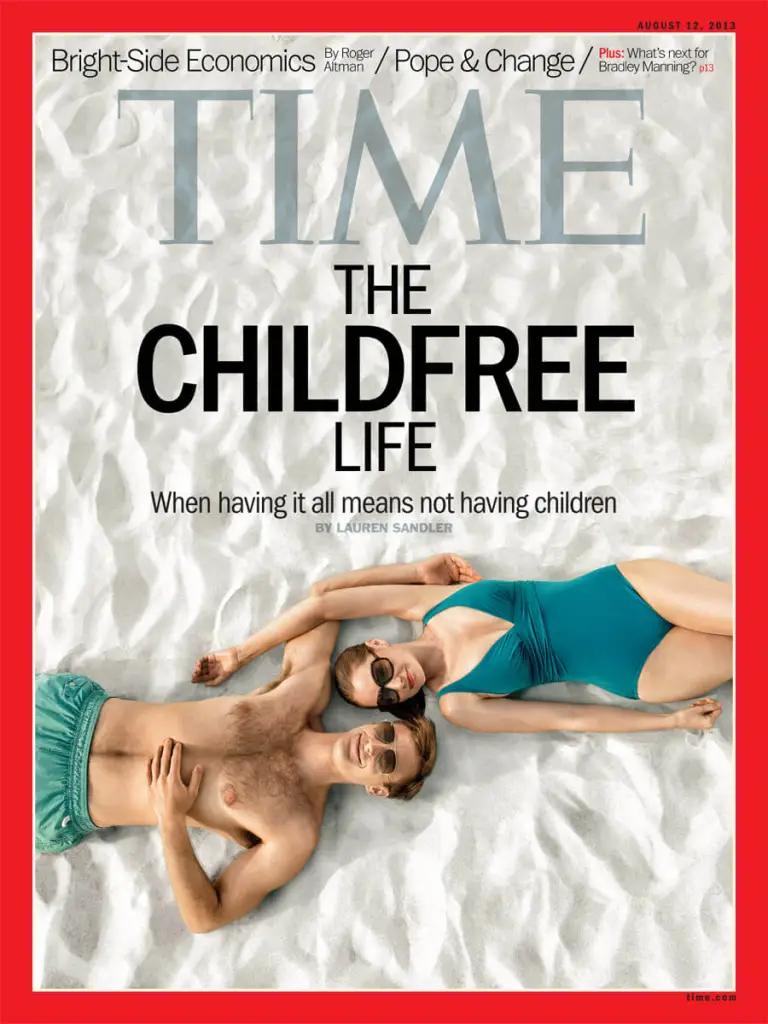

This is not how the phenomenon is portrayed in the media. Magazine cover stories and news articles tout the so-called “childfree” life, assuming all childless women have chosen this fate, waving some sort of feminist flag. But the truth is, these women are not “free” of the children they yearn for. Motherhood is a burden that we would give anything to bear.

In the meantime, the women of this cohort which I went on to dub “Otherhood” in my 2014 reported memoir of the same name, are facing a dating market in which finding a match is more challenging than they expected. American women are now more likely to graduate from college than men. And young women with college degrees are out-earning their young male counterparts. A 2012 Pew Research study found that while two thirds of millennial women say that “being successful in a high-paying career or profession” is of high importance to them, the same is true of only 59% of their male peers.

But don’t call us “career women”—an anachronistic label for when working women were outliers. Today, even most married mothers work. Moreover, Pew reports that young women are significantly more likely than young men to say that a successful marriage is “one of the most important things in life.” Likewise, nearly 60% of women rate successful parenting as one of the most important parts of life, as compared with less than half of men (47%). It’s no wonder why it’s becoming more and more challenging for women to find men who want to commit to the next stage of life.

For this cohort, feminism was never about forsaking love, marriage, and children for a career. Career is additive to, not in lieu of, family. As Betty Friedan wrote so eloquently in the epilogue to the The Feminine Mystique:

The more I’ve become myself—and the more strength, support, and love I’ve somehow managed to take from, and give to, other women in the movement—the more joyous and real I feel loving a man. I’ve seen great relief in women this year as I’ve spelled out my personal truth: that the assumption of your own identity, equality, and even political power does not mean you stop needing to love, and be loved by, a man, or that you stop caring for your kids.

These strong, determined women are not swayed by late 1960/1970s feminists to change our evolutionary nature to do anything in our power to become mothers. Many of these same women invest tens-of-thousands of dollars in fertility preservation and treatments, sticking themselves with needles, going through painful procedures, hoping they will one day be rewarded with a child. Marc Kalan, a board certified reproductive endocrinologist whom I interviewed for Otherhood told me that no patients of his are more compliant than the women who come to him in their late thirties and forties, who have not found a partner, and want to have a baby. Even those with a less than 5 percent chance of conception are undeterred.

Still, some on the right assume that feminism has tricked us into believing that we could have it all, leaving our wombs bereft of life and our lives bereft of meaning. On a recent episode of his podcast, even professor Jordan Peterson, for whom I generally have great respect, has opined that only motherhood, and the sense of responsibility it imbues, can enable women to development into adulthood. But this implies that childless women live in a kind of existential limbo, seen neither as children nor adults; neither cared for nor caregivers; neither fully formed women nor life-informed adults.

But we are not a second sex within our own sex; we are not other to mother.

In a 2012 study I partnered on with the communications firm Weber Shandwick, we found 23-million PANKs, or Professional Aunts No Kids, the term I coined to describe child loving, childless women. That’s one-in-five North American women. These generous aunts contribute to the development of our nieces and nephews by relation, our friends’ children, and children around the world. This tribe understands that while babies are born from the womb, maternity is born from the soul and there are many ways to mother.

While my dream of twin daughters did not come true for me, it turns out my intuition wasn’t completely off. As the Yiddish proverb goes: “We plan, and God laughs;” I am blessed with not one, but two sets of twin nieces. My dream came true for my brother and sister-in-law, twice, and I could not love all my nieces and my nephew more if I tried.

It’s not the life I expected, but in many ways, it’s a life beyond my expectations.