Education

How the Science Wars Ruined the Mother of Anthropology

Both revered and despised for the image of humanity she presented to the world, and for her conclusions about the Samoan people, in particular.

Part I: Margaret Mead’s Original Sin

When I was about 23, I embarked on a lone trip around the Vanuatu Islands. I eventually wound up on the isolated Maskelyne Island, quite a few days away from civilization in the Western sense of the word. A man had just died and many suspected that witchcraft was involved in cursing his food. For a week I attended the extensive funeral ceremonies, dove on the reef in my spare time, and drank kava with the locals at night. It all sounds very romantic, but the truth is that there was something quite off-putting about being surrounded by hundreds of people from a different culture; an unusual state of loneliness begins to creep in, accompanied by a deep desire to connect with something – anything – from Western culture. Climbing aboard the cargo vessel Big Sista to hitch a ride to Espiritu Santo, I remember hearing a Taylor Swift song on the radio. I’ve never appreciated Taylor Swift so much.

However, my journey did leave me with a newfound and abiding respect for the anthropologist Margaret Mead. At the same young age of 23, Mead travelled to the Samoan Islands to the east of the Vanuatu in the South Pacific Ocean to study the islands’ Polynesian people. On a cloudy Samoan day in August of 1925, she stepped off the S.S. Sonoma in Pago Pago Bay, Tuttuila, and began her research. By the end of her career, she was celebrated as the mother of anthropology, both revered and despised for the image of humanity she presented to the world, and for her conclusions about the Samoan people, in particular.

At first, her conversations with the Samoans did not go especially well:

Mead: When a chief’s son is tattooed they build a special house, don’t they?

Asuegi: No, no special house.

Mead: Are you sure they never build a house?

Asuegi: Yes. Well, sometimes they build a small house of sticks and leaves.

Mead: Was that house sacred?

Asuegi: No, not sacred.

Mead: Could you take food into it?

Asuegi: Oh no. That was forbidden.

Mead: Smoke in there?

Asuegi: Oh no, very sacred.

Mead: Could anybody go into the house who wished?

Asuegi: Yes, anybody.

Mead: No one was forbidden to go in?

Asuegi: No.

Mead: Could the boy’s sister go in?

Asuegi: Oh no. That was forbidden.

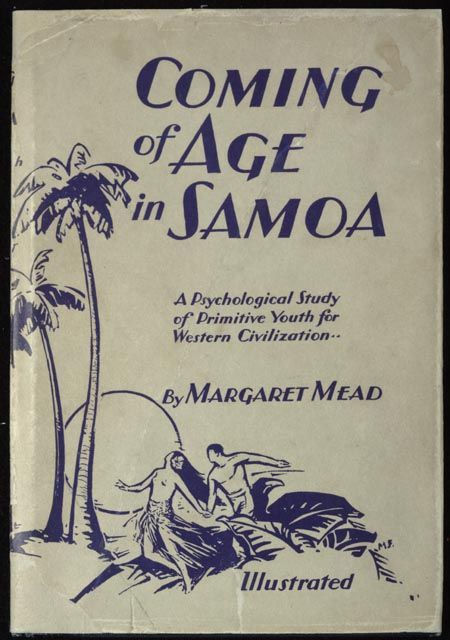

Mead later recalled that she could have “screamed with impatience.” To make matters worse, the native Samoans would often take her belongings and redistribute them according to ceremonial obligations. But, eventually, she began to make progress. Mead developed close friendships with a small and dedicated group of young girls who became her chief informants. She was made a taupou, a ceremonial virgin, despite having a husband back in the United States. Before long, Mead was considered a respected honorary member of the society, and her research project blossomed. A few months and a tropical hurricane later, Mead returned to the United States, and in 1928, she published the results of her research, Coming of Age in Samoa: A Psychological Study of Primitive Youth for Western Civilization.

It was her instructor, the ‘father’ of American anthropology Franz Boas, who had sent her on a mission to Samoa. In The Mind of Primitive Man, Boas had set out to draw a sharp distinction between race and culture in order to defend his thesis that differences between the world’s peoples are overwhelmingly the result of upbringing rather than evolved traits. One of Mead’s mentors, Ruth Benedict, popularized Boas’s argument in her famous 1934 work Patterns of Culture: “Most people are shaped to the form of their culture because of the enormous malleability of their original endowment. They are plastic to the molding force of the society into which they were born.” Mead was intellectually enthralled by Boas, and deeply attached to Benedict, with whom she would later enter into an intimate relationship. Boas and Benedict had sent the young 23-year-old Mead to the South Pacific on an assignment: investigate the degree to which adolescent behavior is different from Western society, and thus the malleable outcome of cultural differences.

Given her mentors’ emphasis on cultural explanations for human behavior, Mead’s preferred conclusion ought to be obvious. Sex before marriage was common in Samoa according to Mead, where young girls were free to experiment with their sexuality without being interfered with by adults. The cover of her book depicted two young lovers, hand in hand, under a moonlit coconut tree, and the passages of Coming of Age in Samoa that captured the audience’s attention were those that focused on the exotic and the romantic:

These affairs are usually of short duration and both boy and girl may be carrying on several at once…These clandestine lovers make their rendezvous on the outskirts of the village. ‘Under the palm trees’ is the conventionalized designation of this type of intrigue. Very often three or four couples will have a common rendezvous, when either the boys or the girls are relatives who are friends. Should the girl grow faint or dizzy, it is the boy’s part to climb the nearest palm and fetch down a fresh coconut to pour on her face in lieu of eau-de-Cologne.

Contrary to a very different picture Mead would later paint of New Guinea in Sex and Temperament in Three Primitive Societies, in Samoa she emphasized the leitmotif of the noble savage, a people among whom violence and rape were exceedingly rare. How she knew this is dubious. More dubious still was her definition of rape. Mead acknowledged, as she put it, that some men “stealthily appropriate the favors which are meant for another,” but she insisted that this was quite different to rape as understood in the West. A meototolo is a man who would wait until he knows that a woman is lying in the dark, waiting for her lover to enter the hut. The man would then sneak in and pretend to be the lover under the cover of darkness, engaging in sexual activity until his real identity were exposed. At points, Coming of Age in Samoa seems to adopt a romantic or poetic sensibility at the expense of the clinical observation expected of a scientist:

Do not think it is he who whispers softly in her ear or says to her, “Sweet-heart, wait for me tonight. After the moon has set, I will come to you,” or who teases her by saying she has many lovers. Look instead at the boy who sits afar off, who sits with bent head and takes no part in the joking. And you will see that his eyes are always turned softly on the girl. Always he watches her and never does he miss a movement of her lips.

The world fell in love with Mead’s romantic description of a paradise of free love gemmed away in the tropical South Pacific – a society with little jealousy, violence, or rape. The liberal journalist Freda Kichwey wrote in The Nation that, “Somewhere in each of us, hidden among our more obscure desires and our impulses of escape, is a palm fringed South Sea Island.” Samuel Schmalhausen spoke of the “naturalness and simplicity and sexual joy” of Samoa.1 Within the emerging field of anthropology, Mead became a revered figure. Hundreds of anthropology books relayed her research, promoting the overarching lesson that sexuality and violence are entirely malleable and changeable in cultures. The conclusions Mead drew about the uniqueness of Samoan adolescent life validated the early American anthropological project to explain human behavior in terms of cultural specificity. When Boas and Benedict passed away, Mead became the unchallenged icon of the discipline, the mother of anthropology, and as Time called her, “mother of the world.”

But in the 1960s, Mead began hearing of a then-obscure New Zealand anthropologist named Derek Freeman, who had begun working in Samoa 1940 when he was also 23, and now taught at the Australian National University in Canberra. She had heard rumors that Freeman contested several of her claims in Coming of Age in Samoa and so, during a trip to Australia in 1964, she visited Freeman in his office to ask about the nature of his objections. During that encounter, Freeman informed her that he was preparing a public refutation of her work. When Mead asked to see Freeman’s thesis on Samoan social structure, he was left momentarily speechless. “I’ve never stuttered in my life,” he later recalled in embarrassment. “You’re trembling like jelly,” Mead told him. But what he presented that day shook her, and by the time the two-hour meeting was over, it was Mead who was left “agitated” and “shaken.”2

In 1977, 13 years after their first meeting, Freeman sent Mead a chapter of his forthcoming book refuting her work. At the time, Mead’s secretary replied that she was too sick to read it, and she died of cancer shortly after. In 1983, having postponed publication of his thesis as a mark of respect, Freeman finally published Margaret Mead and Samoa: The Making and Unmaking of an Anthropological Myth, in which he contested almost every one of Mead’s romantic depictions of Samoan society. One of Freeman’s core claims was that sex before marriage is actually forbidden in Samoan culture, and he described a puritan ceremony that painted the Samoans as obsessed with virginity:

The young woman was then taken by the hand by her elder brother or some other relative, and led toward her bridegroom, dressed in a fine mat edged with red feathers, her body gleaming with scented oil. On arriving immediately in front of him she threw off this mat and stood naked while he ruptured her hymen with “two fingers of his right hand.” If a hemorrhage ensued the bridegroom drew his fingers over the bride’s upper lip, before holding up his hand for all present to witness the proof of her virginity. At this the female supporters of the bride rushed forward to obtain a portion to smear upon themselves before dancing naked and hitting their heads with stones until their blood ran down in streams, in sympathy with, and in honor of, the virgin bride.

If, on this occasion, there was no blood then it was assumed that the girl was not a virgin. Severe punishment would then ensue, with the girl beaten as everyone present shouted a word that roughly translates as “prostitute.” Freeman even recounted a story in which a girl was forced on her wedding day to swim out to sea and never return after her premarital sexual experience was revealed. In 1963, a girl was accused by another of having sex before marriage, and travelled 40 miles to have a gynecological examination that would disprove the accusation. The very fact that Mead had been made a taupou, a ceremonial virgin, showed how institutionalized virginity was.

Freeman then went on to criticize Mead’s claims about rape. After all, how plausible is Mead’s claim that, “The idea of forcible rape or of any sexual act to which both participants do not give themselves freely is completely foreign to the Samoan mind.” Freeman’s breakdown of colonial data on reported acts of rape found it to be 20 times higher than in England at the time, with Freeman concluding that “the Samoan rape rate is certainly one of the highest to be found anywhere in the world.”

And what about Mead’s assertion that Samoa was a relatively peaceful society? Freeman went on to table the evidence of Samoa’s long history of intertribal warfare. During intergroup raids, children were reportedly hung in trees and had spears thrown at them, heads were hacked off and paraded, and those captured were sometimes eaten in acts of cannibalism.

Countless readers had formed a romantic image of the Samoan people from Coming Of Age in Samoa, but now Freeman had broken the spell. The people most blindsided by Freeman’s book were those anthropologists who had stood in front of lecture audiences and fed students Mead’s image of Samoa. Some of them immediately attacked the book. Anthropologist Laura Nader, sister of independent US politician Ralph Nader, called Freeman’s book a “Right-wing political backlash” for questioning the influence of culture on human behavior, and a vote by American Anthropological Association condemned the book as unscientific.

Over the next few decades, Mead’s reputation hung precariously in the balance as anthropologists and evolutionary psychologists battled it out in the nature-nurture controversy. However, the cruelest blow to Mead would come from anthropologists themselves.

Part II: The Real Margaret Mead

Unlike the American anthropologists who preached Mead’s findings, Samoans themselves tended to look upon Mead’s work negatively. Some of the Samoan elders burned copies of Coming of Age in Samoa when they realized what Mead had written, and for some time libraries in Samoa didn’t stock the book. Samoan anthropologist Unasa L. F. Va’a called it “one of the worst books of the twentieth century.”3 One of the questions that preoccupied Freeman was how Mead arrived at the erroneous conclusions she drew in her book. He decided that Mead’s own research came mostly from interviews with women, particularly young women, who are hardly the best informants when it comes to matters of historical warfare and violence. On the subject of promiscuity, Freeman conjectured that Mead was the victim of a hoax by her young female informants: “All the indications are that the young Margaret Mead was, as a kind of joke, deliberately misled by her adolescent informants.” In 1987, a few years after Margaret Mead and Samoa was published, it was discovered that one of Mead’s close informers in 1926, Fa’apua’a Fa’amu, was still alive, and wished to swear on the Bible to clear the record on what she had told Mead all those years ago about sexual relations among the Samoans:

We said that we were out all night with the boys; she failed to realize that we were just joking and must have been taken in by our pretenses…She must have taken it seriously but I was only joking. As you know, Samoan girls are terrific liars when it comes to joking. But Margaret accepted our trumped up stories as though they were true.…Yes, we just lied and lied to her.

Frank Heiman’s 1988 documentary Margaret Mead and Samoa largely painted Mead as being undone by Freeman. Freeman, meanwhile, was portrayed as in touch with Samoans, and an irreverent lone warrior, fighting to rescue anthropology from the shackles of groupthink:

The embarrassment caused by Freeman’s critique goes to the heart of the nature-nurture controversy – the longstanding dispute about how far human behavior is shaped by our culture or by universal attributes of human nature rooted in our evolutionary biological history. Most animals behave as they do due to their evolutionary history, and Freeman, like evolutionary psychologists, assumes a model of complex interaction between our own evolutionary history and cultures. Many anthropologists, on the other hand, favor explanations from culture alone. Samoa was a case study to these anthropologists, and a demonstration of culture’s potency in molding behaviors like rape, violence, and sexual restraint.

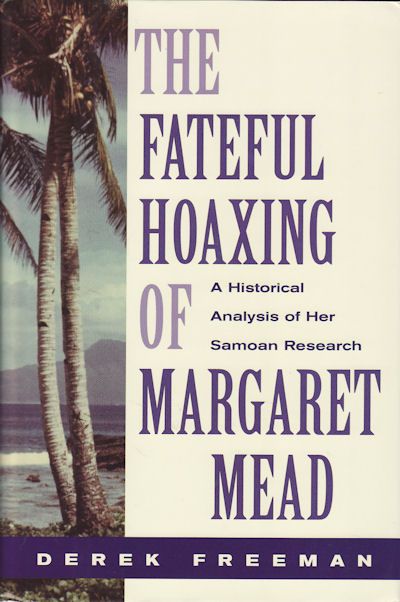

After Fa’apua’a Fa’amu’s confession, Freeman published a second book in 1999 intended as a declaration of victory. In The Fateful Hoaxing of Margaret Mead, he says, “All that now remains to be sought is a full and accurate explanation of the passionate and irrational reaction to my refutation of 1983…” Outside of academia, Freeman experienced minor celebrity. He was invited onto the Phil Donahue Show in 1983, and in 1996 the Sydney Opera House staged a play about him entitled Heretic. Meanwhile, inside of academia, many university students will find, as I have, that the entire controversy has been swept under the carpet. No mention is made of Freeman in anthropology courses. Instead, business continues as usual, and it is possible to complete an entire degree in anthropology without hearing any criticism of Margaret Mead’s Coming of Age in Samoa. This is a travesty – one among many in the humanities.

That being said, researchers in fields that challenge anthropology’s theoretical outlook on the malleability of human behavior take a similarly rigid stance on the issue in the opposite direction. Those of us who incorporate evolutionary views into our picture of human nature grow tired of anthropologists and their stubborn insistence that all human behavior must be explained by culture alone. But this can lead evolutionists to discard a more careful analysis of complex issues. Off-hand dismissals of Mead’s conclusions litter the literature of evolutionary psychology. There, Mead is treated with scorn and derision. For example, evolutionary psychology pioneers Margo Wilson and Martin Daly write in Homicide of Mead’s “fantastical misrepresentation” of Samoan culture, which has been “made perfectly clear by Derek Freeman’s surgical expose.” Matt Ridley, another otherwise brilliant science writer, takes a stab at Mead in Nature Via Nurture when he says, “To find a society in which young girls were sexually uninhibited, she had to visit a land of the imagination.”

Although Mead’s analysis is obviously highly questionable, the degree to which her work misrepresented Samoan society remains an open question. In 2009, the anthropologist Paul Shankman published his book The Trashing of Margaret Mead in which he reconsiders the evidence. Shankman describes Freeman as an unruly character marked by mental instability, a vindictive desire to ruin the careers of other anthropologists, and plain rudeness (Shankman recalled a nightmare experience when he gave a lecture at ANU and Freeman sat behind him opening and reading his mail so loudly that Shankman had to ask him to stop). This ad hominem attack on Freeman might seem like a desperate effort to evade his refutation of Mead, or to seek revenge on Freeman, but Shankman does succeed in raising some important questions. For example, although virginity is prized in Samoa, it is much more prized among the taupou, the ceremonial virgins of higher status who go on to marry the chiefs. Among the lower status girls, sexual mores were more relaxed and some of these girls did sleep with men before marriage as even Freeman’s data found. Other aspects of Shankman’s belated defense of Mead are more contentious. For example he dismisses Fa’apua’a Fa’amu’s testimony about lying to Mead as irrelevant due to her advanced age and sometimes contradictory statements. He also speculates that Fa’apua’a Fa’amu’s testimony was probably not influential on Mead’s wider conclusions because she was only one of 25 informants. These are important qualifications to what is often presented as Freeman’s decisive refutation of Mead’s work.

Anybody with any experience of living among another society will understand the difficulty of interpreting a culture, whether physically, emotionally, or intellectually. Mead was a 23-year-old pioneer who had travelled to the South Seas to record the life of an island people better than most of us could. It is important to remember that the emphasis placed on culture rather than biology by Boas, Benedict, and Mead also served a noble purpose in thwarting the theories of the early twentieth century’s racial eugenicists. We probably owe more to these three anthropologists than to anyone else for our modern scientific understanding of race. And, although Mead is today seen as an icon of cultural determinism and as hostile to more evolutionary perspectives on human nature, this is not a wholly accurate representation of her views. Writing in Male and Female in 1949, Mead notes that in every society she has studied, there is a particular coalescence of behaviors that can be described as male or female and un-malleable by culture: “Different as are the ways in which different cultures pattern the development of human beings, there are basic regularities that no known culture has yet been able to evade.”

In 1976, Bill Irons and Napoleon Chagnon organized a symposium at the American Anthropological Association on biologist Edward O. Wilson’s book Sociobiology and similar research focused on evolutionary aspects of human behavior. At one meeting of the Association held before the symposium, anthropologists against sociobiology tried to have the conference banned until Mead stood up and told the room that a ban on a sociobiology symposia would be tantamount to a book burning.4 During that symposium, Wilson was famously doused in iced water by a group of Marxists (Wilson later summarised Marxism, “wonderful theory, wrong species”). Yet, in his autobiography, Wilson recalls his exchange with Mead during the conference, “I was nervous then, expecting America’s mother figure to scold me about the nature of genetic determination. I had nothing to fear. She wanted to stress that she, too, had published ideas on the biological basis of social behavior.”5 In fact, an early writing by Mead indicates that she too was worried about being associated with eugenics if she spoke too openly about innate human capacities. During the Second World War, she wrote that “further study of inborn traits will have to wait until less troubled times.”6 Perhaps Freeman’s greatest mistake was his attempt to cast Mead as a cultural determinist, and this error has been lapped up by evolutionary psychologists ever since. Nor are they Mead’s only enemies.

What Paul Shankman fails to mention in The Trashing of Margaret Mead is that the dispute over her work extends to anthropologists engaged in the so-called ‘science war’ between objective anthropologists and their New Age counterparts. Just as you won’t hear Derek Freeman’s name in anthropology classes, it is becoming rare to hear Mead’s name either. Perhaps this is partly because Mead is felt to be an embarrassment to anthropology in the entire nature-nurture controversy. But, unfortunately, the problem runs deeper than that. Anthropology as a field has become increasingly skeptical of all anthropologists who died before the 1980s, primarily for ideological reasons. Mead championed the idea of anthropology as a science of mankind, a perspective that has, alas, been lost under the rubble left by postmodern activism in the field. Today’s anthropologists criticize Mead as belonging to the earlier generation of “Rustling-of-the-wind-in-the-palm-trees-school-of-ethnography,”7 which allegedly exoticized other cultures and repackaged them for Western entertainment. Curiosity about other cultures is treated with skepticism and even suspicion by the new postmodernist regime in anthropology.

Against the militant relativism that now plagues ethnic studies, Mead held that there is such a thing as progress; some societies can improve by adopting aspects of Western culture, and we can learn from other cultures ourselves. Contrary to the fears of those who suppose that overly cultural explanations of human behavior will always lead one to conclude in favor of radical social engineering, in Coming of Age in Samoa Mead warns us that changing our society can only be done piecemeal, just as language can only be changed in haphazard fashion. It was her mentor Ruth Benedict who warned in Patterns of Culture that the West cannot simply choose to emulate other cultures: “The romantic Utopianism that reaches out toward the simpler primitive, attractive as it sometimes may be, is as often, in ethnological study, a hindrance as a help.” These are hardly the statements of the activists we find lurking in the fusty corridors of the humanities today.

Hard pressed between the ire of evolutionary psychologists on the one hand, and the science war that has engulfed anthropology on the other, it is hard to find a friend of Mead nowadays. Lola Romanucci-Ross once told Mead in a most exemplary fashion, “What you have in anthropology and for the world is not Samoa dependent, it really doesn’t matter whether you were right or wrong about Samoa.” There are those of us who admire Mead’s early courage and appreciate what she accomplished in popularizing anthropology, flaws and all. Particularly those of us with a scientific view of anthropology who are being driven out of the discipline in a witch-hunt by the repressive forces of activist ideology. I often wonder what Mead would think about the state of anthropology today.

References:

1 Freeman, Derek. (1983) Margaret Mead and Samoa. Harvard University Press.

2 Shankman, Paul (2009). The Trashing of Margaret Mead, University of Wisconsin Press.

3 Shankman, Paul (2009). The Trashing of Margaret Mead, University of Wisconsin Press.

4 Chagnon, Napoleon. (2013). Noble Savages. Simon & Schuster.

5 Wilson, Edward. (2006). Naturalist. Island Press.

6 Foerstal , Lenora & Gilliam, Angela (1992). Confronting Margaret Mead: Scholarship, Empire, and the South Pacific. Temple University Press.

7 Lutkehaus, Nancy 1995. “Margaret Mead and the ‘Rustling-of-the-wind-in-the-Palm-Trees- school’ of Ethnographic writing.” In Women Writing Culture. Berkley, University of California Press.