Education

China: Zero Tolerance for Academic Freedom

China quickly found itself facing dissatisfaction from those steamrollered by a policy of growth at all costs, in spite of the country’s economic and diplomatic successes.

Universities will be closely scrutinised, professors will be evaluated and the Party will punish those lacking ideological firmness. Such is the program released by Xi Jinping’s government to coincide with the Communist Party congress, where Xi is seeking to reinforce his authority as a world leader.

Efforts to control universities and disregard academic freedom are also taking place abroad. In early September, Reuters and The Guardian exposed efforts by Chinese authorities to partially restrict access to the American Political Science Review from within China. The Review, one of the most reputable journals in its field, is published by the prestigious Cambridge University Press (CUP). Ultimately the publishing house resisted the Chinese pressure, but the news has sparked upset, coming just a few weeks after another controversy that shook the foundations of academia.

The “China Quarterly” affair

In August, China scholars from around the world learnt that Beijing had demanded that Cambridge University Press withdraw 315 articles and book reviews from China Quarterly, produced by University of London’s respected School of Oriental and African Studies and published by CUP.

These articles dealt with topics considered sensitive by the Chinese government: the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests; Mao Zedong and China’s Cultural Revolution; ethnic tensions in Tibet and Xinjiang; Taiwan; and anything relating to democratic reform.

CUP complied, pulling the offending articles from their Chinese site, explaining that it would rather withdraw a small number of articles of interest to a handful of academics, in order to ensure the continued availability in China of its numerous other academic and educational publications.

Led by China Quarterly editor Tim Pringle, academics and NGOs expressed outrage that CUP would favour its own commercial interests above academic freedom, and threatened to boycott the publishing house.

Faced with protests, the Chinese government defended its actions in an editorial published in the August 20 edition of the Global Times, stating that, while it respects academic freedom in the UK, China has the right to decide what can be published within its borders.

Three days after the censorship came to lighy, CUP had a sudden change of heart, and made the 315 articles available again.

Around the same time, the US-based Association of Asian Studies (AAS) revealed it had received a similar demand but did not comply.

Ideological battle

The controversy highlights the oppressive nature of the government of the People’s Republic. Despite the undeniable international character of Chinese universities, higher education and research must tow the party line.

Deng Xiaoping’s late-1970s policies of economic reform and opening-up enabled the country to become a laboratory of ideas in the last quarter of the 20th century. But for the past decade or so, China appears to be engaged in an ideological battle against the West.

Following the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, China overtook Japan as the world’s second largest economy, behind the US, which was itself weakened by the 2007-2008 financial crisis and the resulting severe recession.

Yet China quickly found itself facing dissatisfaction from those steamrollered by a policy of growth at all costs, in spite of the country’s economic and diplomatic successes. Many Chinese intellectuals began to think the lot of their fellow citizens should be improved with a final – political – reform.

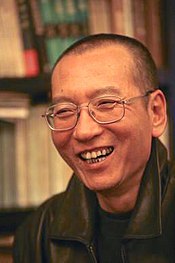

Led by writer and university professor Liu Xiaobo, one of the key activists of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests, hundreds of intellectuals signed the Charter 08, a manifesto in favour of democratising the regime. For this Liu was sentenced in 2009 to an 11-year prison term. He was released in July 2017 and died a few days later.

Document #9, the “anti-subversion kit”

Xi Jinping’s rise to power in 2012-2013 signalled a new era in the curtailing of freedom of thought. Fearing any threat to the purity of their ideology, Communist Party of China (CPC) leaders released a handbook listing the subversive ideas to be eradicated, the infamous Document #9.

The following topics are now banned from public discussion: Western constitutional democracy, the universal nature of human rights, the empowerment of civil society, multiple interpretations of history, and anything questioning the validity of Chinese economic reforms and socialism.

While post-Mao China was not free of taboos, they were usually limited to the “three Ts”: Taiwan, Tiananmen and Tibet. Several things have changed since 2012. Firstly, the publication of Document #9 expanded the scope of unacceptable ideas: any subject, without exception, could now be censored.

Secondly, Chinese universities are now the reluctant front-line soldiers in this ideological battle: in 2015, the Minister for Education urged universities to ban the use of textbooks promoting Western values. Lastly, any contravening of the new norm is now subject to severe repression, and the CPC has no qualms about openly resorting to totalitarian tactics.

A violent crackdown

On top of routine intimidation, 248 human rights advocates were rounded up in a brutal mass arrest in July 2015. In the resulting atmosphere of fear, liberal intellectuals no longer think it wise to answer questions from foreign journalists; they practice broad self-censorship and, when possible, wind up living in exile abroad. For those who remain, harassment is commonplace.

These attacks against fundamental rights and specifically academic freedom are now extending beyond mainland China, starting with the special administrative regions. In 2014, several Macau professors were abruptly dismissed; in Hong Kong, the 2015 disappearances of five book-sellers and publishers is still unresolved. These cases reveal the widening cracks in the “one country, two systems” model. Yet Beijing’s influence does not stop there.

In the summer of 2014, the European Association for Chinese Studies had several pages of its program ripped out by the Confucius Institute the day before its biannual conference in Portugal.

The institute apparently objected to advertising from Taiwanese sponsors. That same year, the American Association of University Professors initiated calls for the closure of Confucius Institutes, claiming they undermine freedom of speech on US university campuses.

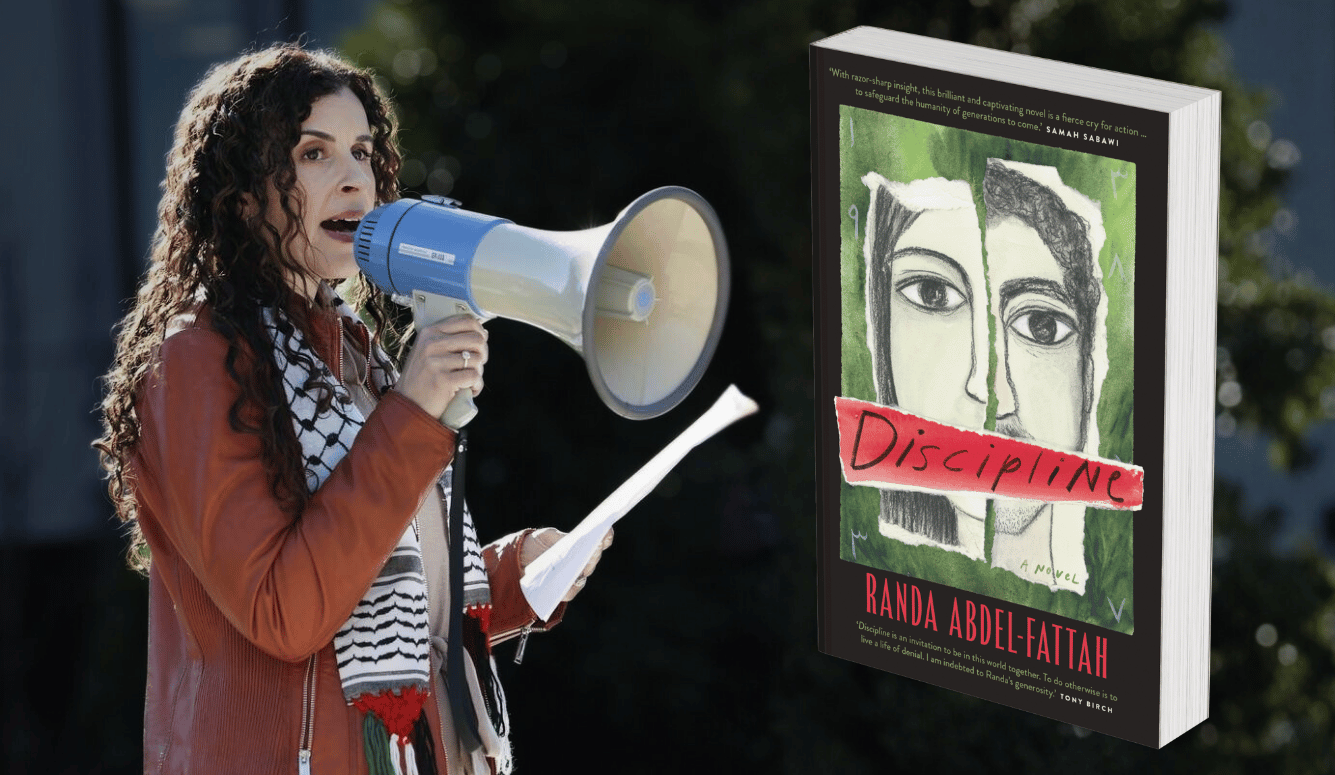

Last month Australia acknowledged Chinese government interference in its universities.

Beijing has been carrying out unprecedented influence and control operations targeting Chinese students as well as Chinese and non-Chinese professors. In response, the Group of Eight (Go8), a coalition of the top eight universities in Australia, has called for a coordinated and measured response.

In 2016, more than a quarter of the 550,000 overseas students enrolled in Australian universities came from China. They represent a significant financial boon for Australian universities, who don’t want to offend the Chinese government. The question is, can the core values of academic institutions be preserved without incurring the wrath of Party leaders?

This article was translated from the French by Alice Heathwood for Fast for Word.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.