Art

E Pluribus Unum: Out of Many, One

The centripetal tendency, if unchecked, ends in a black hole, in narrow paranoia, in the life-denying singularity of fundamentalism or fascism.

F. Scott Fitzgerald famously said that the mark of true intelligence was “the ability to hold two opposing views in mind at the same time.” Actually, I’m not sure that intelligence is the right word. I think it is wisdom that allows us to hold opposing views in mind at the same time.

And it’s certainly true that wiser, more measured voices are drowned out as politics becomes more polarised and the internet makes debate more extreme. Balance is elusive, for all of us in our individual lives, and across society as a whole, and even when attained it is often fleeting.

The search for creative, but lasting, equilibrium is a quest as old as time.

Balance isn’t boring if the stakes are high. Balance isn’t boring if you’re walking a tightrope without a safety net, 1000ft up in the air, while carrying a priceless vase.

Each generation has to maintain the balance of society as best it can. We strive to avoid disaster. That priceless vase might be tradition, or skills, or learning, it might be a healthy planet or ancient wisdom—but we hope to pass it on to our children unbroken, and perhaps even polished up a little.

I am a children’s author and illustrator—and I think that good art can give us insights into what makes a good society. But how do I define ‘good’?

The Greeks linked goodness and beauty, and while that has obvious dangers, it can still be illuminating to think about what makes life beautiful, what makes society beautiful. After all, no one wants an ugly life, an ugly society.

Heraclitus, the most interesting of the pre-Socratic thinkers, believed that creativity, vitality and beauty sprang from the conflict between opposites, that we should actually cultivate creative tension, while at the same time striving for unity.

He used the image of a harp or a bow. A harp string is pulled in opposite directions, but it is the powerful tension that makes music. A bowstring is pulled taut, the opposite ends of the bow want to spring apart—but those opposing forces, drawn together, make the arrow fly.

A modern image of the same idea is electricity sparking between positive and negative poles.

Let me briefly explain how I think this idea applies to art, before I talk about society.

I’m focusing here on traditional art, and popular art, films, novels, etc. because they all have this in common: they aim for aesthetic unity.

(Most modern highbrow culture—art films, literary novels, visual fine art, and architecture—makes a great show of disunity. In fact, that contempt for unity in art is one of the cultural forces that have got us into our current fractured predicament.)

A good story is one of the clearest examples of aesthetic unity. Good storytellers set out to create tension and maintain it across a narrative to keep the reader hooked. That is just as true of Jane Austen as it is of A Game of Thrones.

A story must be whole, unified, yet alive with inner conflict.

Popular or traditional art, in any medium, is a quest for that kind of dynamic, sustained equilibrium.

Visual art can be seen as a three-way tug-of-war between Head, Hand and Heart—between thought, craft and feeling. Each must be at a high level, yet no one quality must dominate at the expense of the others, or else the unity of the whole is lost.

In visual art there is also tension between pattern and representation. (Or design vs realism.) Every painter is a pattern-maker. Monet’s brushstrokes, or Botticelli’s line, make a striking abstract pattern, at the same time as conjuring a compelling representation of a figure or landscape.

The beauty of their pictures is in the balancing act, the high-wire act, the unity the artist achieves between powerful opposing forces.

I am using art just to illustrate the point that polarized forces can be acknowledged as positive, as creative—as long as each is tempered by its opposite. High tension is good—thrilling!—as long as it can be maintained.

In fact, whatever destroys tension, destroys unity.

I have in front of me a ‘consultation document’ from the Mayor of London. No one would say it was thrilling. The sentiments are unremarkable—they are simply the assumptions of the liberal, cosmopolitan worldview. It talks of diversity and openness as unquestionably good, desirable and right. But not every Londoner agrees. There are socially conservative Londoners (of every ethnicity) who want less diversity, less openness. This is especially true in poorer neighbourhoods that bear the brunt of unskilled mass immigration.

I try to see both sides of that argument.

In his book The Road to Somewhere, David Goodhart analyses a value divide in British society, as revealed by countless surveys, and recently exposed by the Brexit vote. He identifies two broad groups, that he calls ‘Anywheres’ and ‘Somewheres’. Liberal, cosmopolitan Anywheres have profited from globalisation, while more rooted, socially-conservative Somewheres have not.

(He estimates that Somewheres make up about 50% of the population, while Anywheres are 25%—the remainder being less definable ‘Inbetweeners’.)

Goodhart focuses on the UK, but the pattern is replicated elsewhere—most notably in the U.S. In Goodhart’s view the balance has tipped too much in favour of the Anywheres—with Brexit and the election of Trump representing a backlash to Anywhere hegemony. Policy making, and establishment culture (including in the arts and architecture) have been dominated by Anywheres, alienating the Somewhere population. It has become a common complaint among conservatives that the diversity so cherished by liberals doesn’t allow for diversity of viewpoint.

Goodhart calls for a new settlement, a new dynamic equilibrium between genuinely diverse views, so that the liberal, cosmopolitan view is tempered by more conservative voices.

‘Nothing in Excess’ was one of the commandments of the god Apollo, carved in stone at Delphi. Tension is good—as long as we aspire to wisdom, to wholeness, to unity, as long as we strive to keep both poles of the argument in mind at the same time, to not deny the validity of either view.

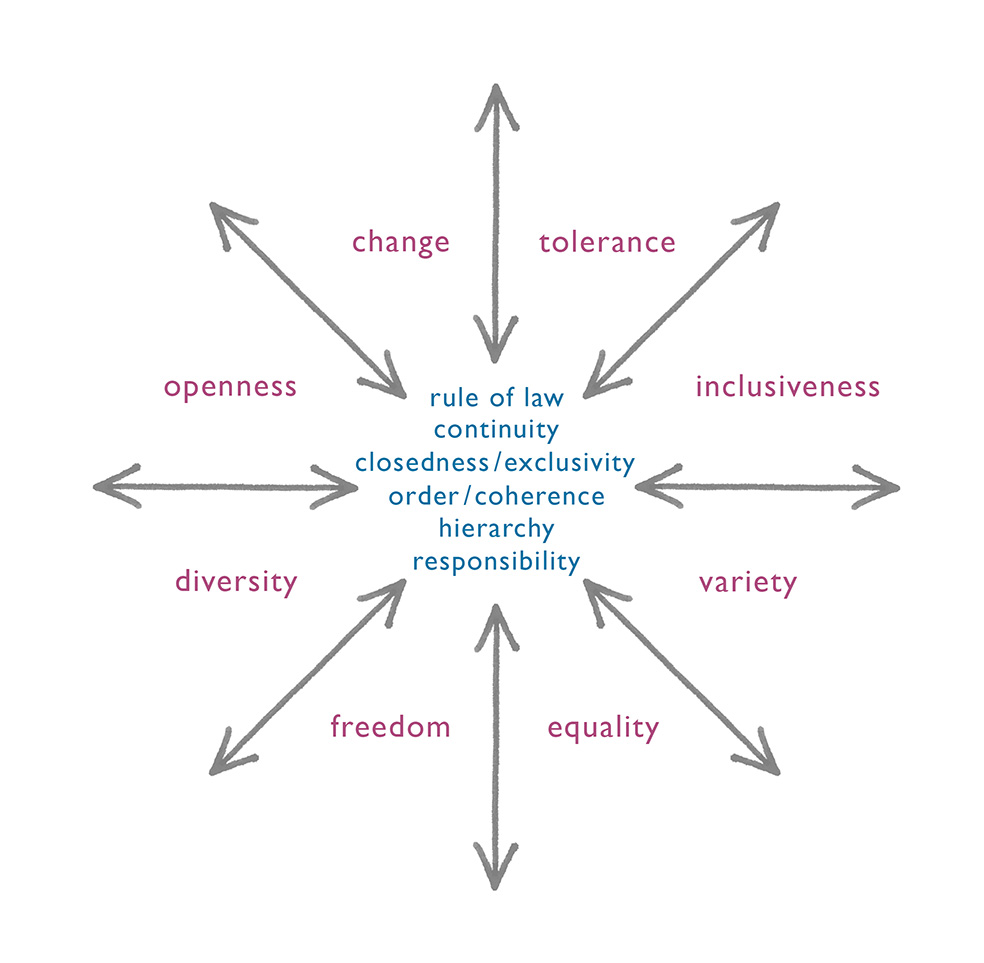

I want to try and make the case for temperance with simple visuals. Here is a list of virtues – and they are all desirable qualities, none is ‘bad’ or wrong. They are the virtues of cosmopolitan liberalism.

Tolerance

Change

Openness / Inclusiveness

Diversity / Variety

Equality

Freedom

But each of those virtues is only one pole on an axis of tension. Each on its own, if taken to excess, is actually dangerous. Each must be tempered by its opposite.

(You may quarrel with some of my word choices—but it is the general principle that I am trying to illustrate.)

Tolerance Rule of Law

Change Continuity

Openness / Inclusiveness Closed / Exclusivity

Diversity / Variety Order / Coherence

Equality Heirarchy

Freedom Responsibility

I could take each of these pairs in turn and explain why, in each case, balance is required. But I’ll concentrate on one or two of the more contentious pairings.

Can ‘closedness’ really be good?

Think of Mecca. Mecca is the only city on earth to exclude entry on the basis of religion: non-Muslims are forbidden. Is that good or bad? If openness was a supreme virtue then Mecca must be forcibly opened to all.

Indeed any exclusive club must be open to all.

Goodhart says that any community, by definition, must have an element of exclusivity.

It is no accident that ‘exclusive’ has also come to be synonymous with luxury. Exclusivity creates value. It creates meaning. It makes things special. Membership of an exclusive club is a privilege. What offends many conservatives about the open borders movement is the feeling that citizenship is thereby devalued, rendered meaningless. The social contract is torn up.

Most people (especially Somewheres) are deeply attached to their homes and neighbourhoods, and invest time and effort over decades to sustain and improve their communities. Belonging, to most people, is a very precious thing indeed. And any neighbourhood ‘belongs’ first to those who have lived there longest.

Openness is good, until it is forced on someone. Think of an interaction between friends. You can’t demand that a friend opens up. You hope they feel sufficiently at ease to be open, but your friend always retains the right to be closed.

Goodhart describes “liberals advocating openness from within their gated communities.” Openness is presented as a supreme liberal virtue, but all too often, in practice, it is only for others. It’s rather like St. Augustine saying “O Lord, give me chastity… but not yet!”

What about freedom? Freedom is often talked of in absolutist terms, as if any infringement on freedom is an injustice. The bounds of free speech can be widely drawn, but there has to be some limit. There are obvious circumstances where we put limits on violent or sexual imagery and language (my daughter’s nursery school, for example). And none of us is entirely free—we are all caught in a web of duties and responsibilities. Viktor Frankl, one of the wisest voices of the 20th century, said that the Statue of Liberty on the East Coast should be balanced by a Statue of Responsibility on the West Coast. Freedom is never an end in itself: it must be for something. We want the freedom to grow, but growing up means taking on increasing commitments, becoming less free.

Again, there isn’t space here to make a comprehensive case that each of these virtues must be held in tension with their opposite. I’m simply trying to look at the whole problem of polarized politics from a new angle.

Here’s a different visualisation of those competing virtues as centrifugal forces vs. centripetal forces, pulling together vs. pulling apart.

The cosy, safe, parochial centre is Somewhereville, the exotic, exciting periphery is Anywhereland.

This wheel is a dynamic structure, it might even be an engine, a perpetual motion machine, actually creating energy, beauty, vitality, from the perpetual conflict between opposites, but only as long as it is working properly, as long as both sides still aspire to unity—despite the inherent tensions.

Excess in either direction leads to disaster. The centripetal tendency, if unchecked, ends in a black hole, in narrow paranoia, in the life-denying singularity of fundamentalism or fascism.

But too much centrifugal force causes society to fly apart, into a free-floating atomised individualism, a heartless world devoid of attachments, and ultimately into anarchy, ‘a war of all against all’.

Some of us are driven to push outwards, some to pull inwards. Our individual taste in ideas, our personal reading of the wrongs of the world, is very often the result of biographical factors. Our political views are often formed in reaction to our upbringing. But of course, the liberal-conservative divide is age related too. We push outwards when young, when we crave separation and autonomy, when every boundary seems like an affront, and when, for a while, we can be giddily irresponsible. We pull inward as we get older, when we want to raise our kids in a pleasant neighbourhood, where we deeply appreciate the social capital of cohesion, stability and trust.

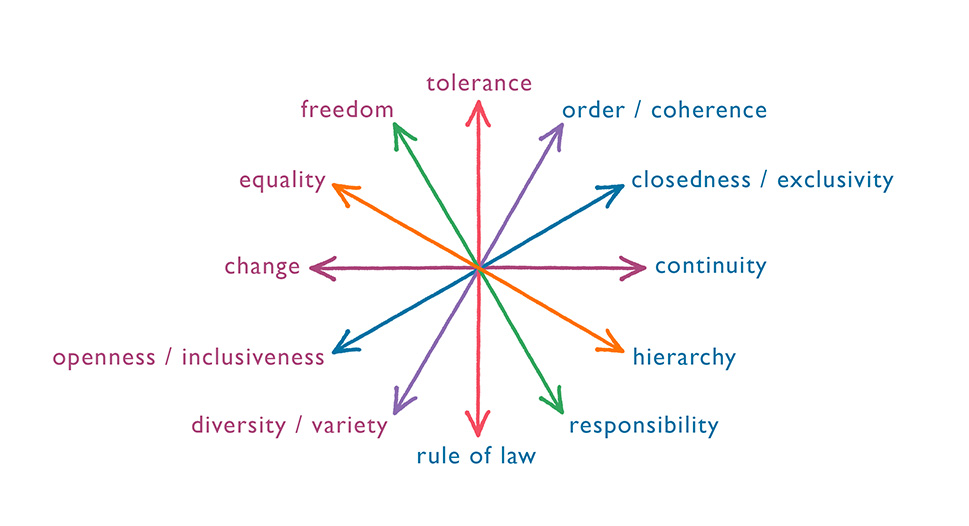

Let’s try a different arrangement again, where each axis of tension crosses a central focal point. The centre is now the target, the bullseye, the point to aim for—the point of balance, the union-of-opposites-in-tension.

It could be seen as a graph—and it would be possible to plot where we are, as a society, on each axis. (Or alternatively, where the Somewheres and Anywheres are.)

Different societies, both ancient and modern, would be different shapes, skewed in one way or the other, each having found a different sort of equilibrium.

The diagram is an image of a centred society, and even though, as it stands, it might be just a functional, bare-bones sort of chart, some readers will see that it is actually edging towards being almost artistic(!).The basic principle here is that wholeness is beautiful—and that what is beautiful is whole. And that symmetries (i.e. balance) can be a source of delight and wonder.

(Postmodernism, in contrast, delights in fragmentation, and asymmetries – witness the postmodernists’ preference for randomness and disjointedness in architecture.)

Pattern-making in the art and architecture of all cultures is a concrete, visual expression of the core values of the society. Pre-modern civilizations, around the world, aimed for wholeness and order, and celebrated that wholeness and order in the symmetries of ornament, and symbolic imagery of cosmic order, telling a story of the culture as a harmonious, intricate, integrated structure. Think of a rose window in a medieval cathedral, or a Buddhist mandala, or the Jain cosmology reproduced here:

Balance is a matter of belief. It requires faith—faith that it is possible, and faith that it is desirable. The loss of faith in any grand narrative has left our society confused, vulnerable and weak. We’re only now, perhaps, beginning to piece together something new.

And I happen to believe it’s possible to find that union-of-opposites-in-tension in even the most bitter, or intractable disputes.

What about this axis of tension?

Could there really be any genuine unity or balance between this awkward pair?

I happen to think that the answer is yes – and that it hinges on how we define the word ‘spiritual’ —a word that sadly has become almost synonymous with woolly-mindedness. Heraclitus had an important message for us there too. But that’s for another essay.