Art and Culture

Feminism Needs to Talk About Responsibility — Not Just Rights

If we ask these accusers to explain themselves, are we blaming the victims? Possibly.

At the age of 47 I suffered what I now like to think of as “The Year of Living Stupidly.” Unlike Sigourney Weaver in the film that inspired me, I did not live dangerously, although there was certainly a lot of drama. That was the year I suffered my last serious crush.

The man was a volunteer at an organisation I feel passionately about. He was also an artist and writer, a fellow seeker in the creative arts. He was also a schmuck, although it took me almost a year to see that. My knowledge of unruly passions, which I joyously cover in my poetry classes, did give me some insight into my condition. However, managing it outside the classroom was something else entirely.

I’m bringing that year out of the darkness and into the light because it’s time for the conversation around women’s rights and responsibilities to change. It’s especially time for those of us who can claim elder feminist statesmanship to ask tough questions of younger women who are dragging bewildered men into court, all in the name of micro-regulating the sex lives of their generation. As a woman who witnessed the blossoming of sexual freedom in the 1970s, I’m appalled by the grasping behaviour of some so-called victims and their zealous minions. It’s as if the essence of sexuality — that glorious and voluntary relinquishing of control — is on trial by women whose capacity for pleasure has been deliberately circumscribed for political purposes.

The Women’s March on Washington provided a visual collage of the madness driving the current rage against men. Although the argument for control over reproductive rights is a sane one, and I support the idea of protests generally, the sight of women dressed up as vaginas and uteruses points to the crazier half of the equations that characterise most feminist demands these days. These are feminists who want governments to provide us with the means to control our reproduction. That’s reasonable, if arguable.

However, to then demand that governments stay out of our sex lives, by not expecting us to use these resources responsibly, is a bit like demanding blank checks for doing nothing. Given the stagnation of most western economies, it’s no surprise that political and fiscal conservatives are saying no. The morality of preventing unwanted pregnancies is not their sticking point; it’s the unhitching of rights and responsibilities, with the demand for rights consistently (and childishly) making up the entire feminist abacus. Were a government to propose that free contraceptives be balanced by a diminished provision of abortions, I’ve no doubt the weeping and wailing of those marchers would become unbearable, this despite the fact that it’s an eminently logical way to apportion resources. For many feminists, simply expecting women to prevent pregnancies instead of terminating them is an affront to our collective freedom.

***

My year of living stupidly comes in handy here and illustrates exactly how the combination of rights and responsibilities works during difficult times. My crush and I formed a working relationship smouldering with sexual energy that was both distracting and intoxicating but going precisely nowhere. That’s because while he was romancing me, he was also setting up house with a new girlfriend, a state of affairs he went to great pains to hide. Discovering his deception was painful, but what was even more so was the recognition that I had allowed myself to become emotionally attached to him on the basis of consciously limited information. That is, I recognized I had overlooked obvious clues, all because I preferred the fantasy of the man over reality. Although I was angry with him and he knew it, I sought out friends who were willing to support me, however gently, in the latter, more difficult version of events, the one where I took responsibility for my choices. I trained my sights on the truly controllable aspect of the problem — myself — and kept my distance from him until the madness, such as it was, passed. These days, I suppose I am to be commended: at least I didn’t take to Twitter to call him a rapist.

If that sounds insulting, it should. There is a concerted effort on the part of some feminists to consolidate sad-sack narratives into blocks of whole theories designed to resist nuanced analysis and criticism. A current example is the Marxist understanding of the woman who, owing to capitalist power imbalances, has no option other than to lash out at her oppressor via the cheap and easy solution of social media. So a woman who has similarly deceived herself into believing a pig’s ear is a prize can now, with the support of global hashtaggers, become feminist icon of the month by destroying the man’s reputation online, a punishment that strikes some of us, with our own histories of less than stellar behaviour, as overkill.

That the woman may have been responsible for some of her own suffering — by staying in a relationship with a known shit — is conveniently swept from the narrative. A bizarre aspect of this thinking has it that women should not be held responsible for their poor judgment owing to the paucity of economic options. Shouldn’t we in the west, with our relative prosperity, be disputing this?

Moreover, since it is 2017 and I do live in a free country, I have a hard time understanding why an unmarried woman would stay with a man she claims has raped her. If this sounds unkind, let me explain: as a young woman I lacked good role models for intimate relationships. My parents were survivors of WWII and as such, suffered from untreated PTSD, making for a chaotic home life. So I deliberately sought out healthier role models while at university. I became a professional observer and what I discovered was a world full of women who would sooner stomp to the nearest exit and shout “You’ve got to be kidding me!” at a man than put up with his disrespect. These women are not hiding in Loch Ness, nor have they been kidnapped by Sasquatches living in the Rockies. They live among us and believe it or not, their response to bad treatment strikes me, and a lot of other women, as proportional, sane and effective.

Moreover, as a de-escalating counter-narrative, it’s desirable. It provides a telling contrast to the spread of implausible victimhood that can be seen in the growing flimsiness of accusations. In Canada, court cases are now being triggered by mere Twitter fights and dating situations gone awry. Ask Gregory Alan Elliott and Mustafa Ururyar. Elliott was taken to court over tweets that were as nasty as the tweets he received from a group of women who had determined, for no discernible reason, that he was a creep. Ururyar ended up in court for a rape charge coming from an accuser who, by her own admission, had over-imbibed one evening, become inappropriately sexual with him in public and then insisted, in the wee hours of the morning, that she wouldn’t be safe unless she went home with him. When he lost his temper, after enduring hours of her bad behaviour, she successfully accused him of rape. Luckily, the judgment was considered so unsound that it was criticised roundly and publicly by other judges — a rarity in Canada — and is currently on appeal. However, in a way that is cringingly predictable, the accuser is being feted by feminist academics while Ururyar, who was in the midst of a Ph.D, has had his career and his life derailed.

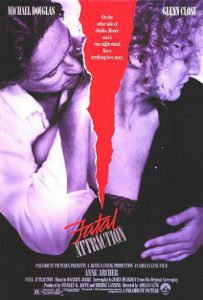

Back in the 1980s, legal experts became interested in drawing up anti-stalking legislation. The archetype most strongly associated with stalking is that of the spurned man, usually a controlling ex-husband, who turns into a predator, hunting down, intimidating and sometimes killing the woman who’s rejected him. It’s an archetype that was subverted, spectacularly, when the 1987 film Fatal Attraction became a hit. That film turned its bunny boiling anti-heroine into a fearsome creature who used sex, anger and guile to threaten that foundation of heterosexual society, the nuclear family. Despite its implicit conservativism, however, the film’s success can be explained by at least one obvious and truthful characterisation: the anti-heroine, played by Glenn Close, wasn’t going to let go of her married lover, played by Michael Douglas, until she was good and ready. The problem, of course, is that her idea of good and ready differed considerably from that of her target; because the unspooling of her rage took a little too long, she was killed before she was finished.

I can’t be the only person who’s wondering if our legal systems aren’t being co-opted by feminists who want to create legal contexts that accommodate the infinite unspooling of rage, rage that often seems misdirected. The efforts of activists to divert the trying of sex crimes to pseudo-legal venues — university administrations and human rights tribunals, for example — suggests this. While an argument can be made for the necessity of safe spaces for rape victims of both genders, the conflicts appearing in the public eye — the frivolous court cases and unsubstantiated accusations on Twitter — seem discordant with that laudable wish.

It’s a simple idea: When a woman is willing to walk away from abuse, taking a man to task for it in public is rarely necessary. It’s recognizing this, along with recognizing that some accusers are also attention seekers, that’s causing women like me to wonder how it is that so many ex-partners have suddenly turned into rapists, especially now that it’s possible to say so on social media.

If we ask these accusers to explain themselves, are we blaming the victims? Possibly. But given the power that courts and social media can wield, there’s nothing wrong with demanding higher standards from our peers.