Art and Culture

Five Stars or Nothing

Ratings and written consumer reviews are important. In markets, they alleviate information asymmetry.

Everyone rating everything out of five is a terrible idea and we are on a trajectory towards this. In April 2016 The Guardian podcast Tech Weekly explored how we are becoming a “rating society”. Uber was the focus. Uber drivers rate passengers out of five and vice-versa. As a passenger, you are apparently less likely to be picked up as quickly if you have a low star rating. And Uber drivers who slip in their ratings risk losing the ability to drive for Uber. Your personal rating is a form of currency.

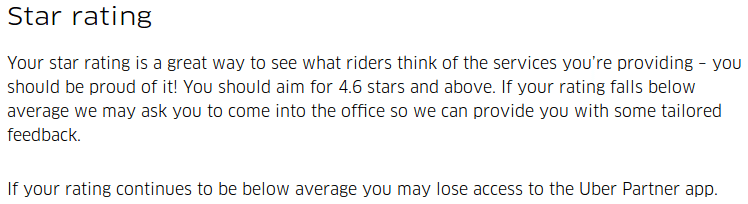

If your Uber driver rating slips “below average” you may need “to come into the office so [Uber] can provide you with some tailored feedback.” The problem is that “below average” would appear to be anything under 4.6 out of 5.

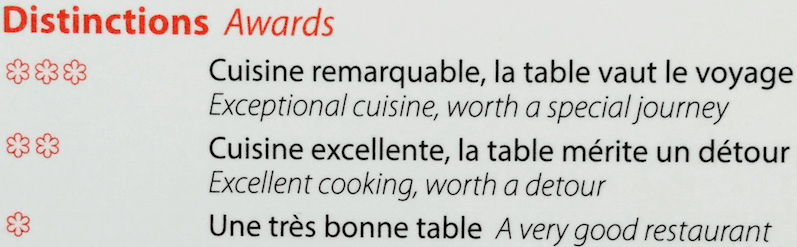

On most historical measures a 4.6 out of 5 is excellent. One star out of a possible three under the century-old Michelin Guide is “a very good restaurant.”

In the past, experts provided the ratings, not the consumers. Ratings were reserved to a select few. The Mobil Travel Guide, now the Forbes Travel Guide, has been using its professional inspectors to award hotels and restaurants with five star ratings since the late 1950’s. The Australasian New Car Assessment Program has been using five stars to indicate vehicle safety since 1993. American hospitals receive government assessed star ratings under HCAHPS (the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems). These ratings apply objective criteria to a particular product or service. And because of this standardisation, you know that a 3 star hotel is going to be decent.

But what about subjective opinions? As the aggregation of film critics’ reviews on websites like Rotten Tomatoes were coming to prominence in 2009, Carl Bialik wrote: “A movie that pleases everyone but thrills no one thus can beat out a polarizing masterpiece.” Although this statement was only directed towards the aggregation of film critics’ opinions, it describes a central problem with democratised star ratings.

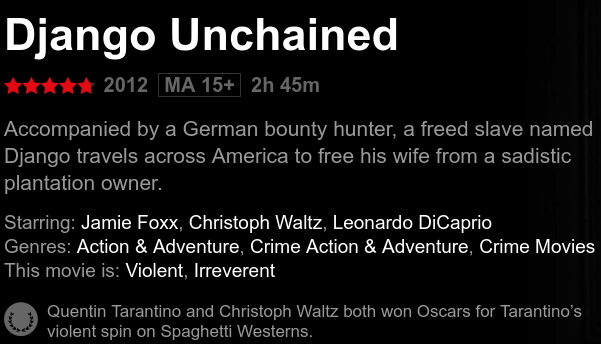

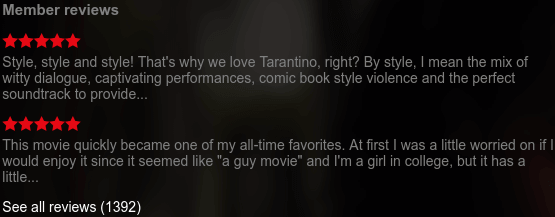

Netflix watchers give Django Unchained a cigarette paper away from five stars.

However, professional critics Margaret Pomeranz and David Stratton both give the movie three-and-a-half stars. Margaret says, “I thought it was terrific up to a certain point and then that last half hour with Quentin Tarantino putting on an Aussie accent with John Jarrett in there…”

It doesn’t matter whose opinion is more valid. What matters is the ease with which I can find the information I need to make a consumer decision. I already know that I tend to agree with Margaret and David (Margaret more so). But in order to find out whether I agree with the Netflix reviewers I have to sift through hundreds of written opinions to find one that aligns with my tastes. Expert critics once provided a shortcut for this type of decision making.

Too often, amateur ratings oscillate wildly between 0–1 star and 5 stars. Scroll through the first several pages of a reviews site for Sydneysiders — “Sydneyr” — and reviewers tend to either have a great experience; or a terrible one.

Is it so hard to give a 2 or a 3? What about 4? Not the best, but better than average. Surely, everyone knows what a 4 is. But we don’t. Because we do not use the same ratings criteria, one person’s rating out of four is not the same as another person’s four. In a community forum thread about Yelp’s star rating system from 2007 Gabe S. of Chicago, IL identifies this problem as follows:

…I view the Star System as important, but it is nothing without the written reviews.

Sometimes a place might be ‘best in class’ and still not deserve 5 stars: For instance, I think Gray’s Papaya is best in class when it comes to Hot Dogs, but I’m not going to give any fast food place in NY 5 stars. But other people might, and the only way to find out is by reading the reviews!

Perhaps we intuitively know this; that we can’t trust ourselves to give the right middling score, and so we become emphatic. YouTube found that most videos were receiving five stars and so they moved to the binary thumbs-up, thumbs-down. The product manager Shiva Rajaraman wrote in 2009, “the ratings system is primarily being used as a seal of approval, not as an editorial indicator of what the community thinks about a video”. This effect is replicated everywhere, and experimenters have shown how we deliberately herd ourselves towards positive consensus.

Ratings and written consumer reviews are important. In markets, they alleviate information asymmetry. They also address the potential for experts’ ratings to be corrupt. But to be useful, a star rating should communicate something more than just general consumer satisfaction or dissatisfaction. A star rating should be consistent across subject matters and ideally provide some objectivity. Reading the reviews should be optional.

Instead, because we can no longer trust the objectivity of star ratings, we must read the reviews to get the information we need. But there is a significant problem with this. We all have limited capacity to sample and interpret others’ opinions before making a decision. So our decisions become biased by a few amateur views, instead of by experts, or instead of an objective standard. Paradoxically, the ratings and reviews we all leave could be contributing to us making poorer decisions about what to consume.

I recently stayed at the Econo Lodge City Central in Auckland, New Zealand. The local independent tourism rating service, Qualmark, awards this Econo Lodge 3 stars. And it was a cheap, middle of the road hotel in which to stay for a night. But at the franchisor Choice Hotels’ website the hotel gets an aggregate 4 stars from verified guests. On TripAdvisor it gets 3.5 stars, which is still 10% up on the local independent expert standard. Let me tell you, it was definitely no more than 3 stars. But did I approve of what was offered given my expectations of a 3 star experience — most definitely (thumbs up)!

User-generated ratings can be made better by incorporating objective criteria, and by weighting what matters. Instead of Choice Hotels asking me to subjectively give the Wi-Fi at Auckland Econo Lodge a score out of 5, I could answer objective questions (like “Was there Wi-Fi?”) and the score could be determined for me. Not each part of the rating is necessarily equal either. The Wi-Fi score should be weighted less than the more important Room Comfort and Room Cleanliness.

Losing the clear marker for consumer expectations that star ratings are able to provide would be unfortunate. If we are going to rate everything we do then the services which ask us to rate things need to become more sophisticated. They should help us to become experts and get us to rate against, as far as possible, an objective standard. If we care to take the time to write a review then we should be capable of answering a few more questions to achieve meaningful star ratings and do better than just 5 stars or nothing.