Art and Culture

Unscrambling the Second Law of Thermodynamics

All these specific conditions (loud volume, correct support, a vowel that works) must be met in order to sing a high note.

The second law of thermodynamics surely qualifies as one of the most talked-about principles in all of physics. Depending on who you ask, it is either incredibly mysterious or fairly mundane. Some physicists think the second law is connected to fundamental ideas such as time and the origin of the universe,1 yet it is also an aspect of everyday experiences, such as how a morning cup of coffee cools down, or the fact that you cannot unscramble an egg. The second law has even been invoked by rock band Muse to explain why, in their view, economic growth cannot continue for much longer.2 However, trying to find a clear explanation of what the second law actually is (and why it is true) can be a frustrating experience.

I first encountered the second law as a teenager, while reading an issue of the fundamentalist Christian magazine Creation, given to me by my grandmother. Since the article’s author wanted to argue against biological evolution, it claimed that the second law of thermodynamics implies evolution is impossible. Its definition of the second law was that disorder always increases with time. At first glance, this does seem incompatible with evolution by natural selection, which can lead to more complex, “better designed” organisms over time.3 At the time, I thought it was unlikely that mainstream biology would flagrantly contradict mainstream physics, so I remained sceptical of this argument, even though I couldn’t understand the counterarguments I found on the Internet at the time.

During my first university physics course, I was excited when I learned we’d be studying thermodynamics. Finally, I thought, I would be able to understand the second law properly (along with the other, less popular laws). Alas, my expectations were not met, despite having a good lecturer. Instead of discussing big-picture issues like evolution, economics, or cosmology, we worked out the maximum possible efficiency of refrigerators and steam engines. I’m sure these are interesting in their own ways, but I was disappointed.

The version of the second law we studied was related to concepts of heat and temperature, and little else. A familiar consequence of this version of the second law is that heat always flows from a hot object to a cooler one, and not the other way around. Your morning cup of coffee cools down, and heats up the air around it; it doesn’t heat up further while cooling the room, even though that possibility is compatible with other laws of physics such as the conservation of energy.

The second law is formalised by defining a quantity called entropy. When heat flows out of one object and into another, the first object’s entropy goes down, by an amount that depends on its temperature. The change in the entropy is the amount of heat energy transferred, Q (usually measured in joules), divided by the temperature of the object, T1, measured in Kelvin. When that same heat energy flows into another object, that object’s entropy goes up by Q divided by the temperature of the second object, T2. The second law of thermodynamics can then be stated as, if you add up all of the changes in entropy of all the objects you are studying, the result must be a positive number or zero. It can’t be negative. In other words, the total entropy must either increase or stay the same. When a cup of coffee cools down its entropy decreases, but the entropy of its surroundings increases by an even greater amount, since the coffee is hotter than the surroundings.

The version of the second law I just described, usually attributed to the 19th century German physicist Rudolf Clausius, certainly has its uses. However, it is a far cry from the lofty fundamental principle I had expected to learn. What did it have to do with evolution? The illusion that organisms are well-designed doesn’t have anything to do with heat being transferred. It doesn’t have much to do with the economy either, except very indirectly, because machines are useful and the second law prohibits certain kinds of machines.

Confusingly, as we learned the Clausius version of the second law, we also discussed phenomena such as gas diffusion, shown in this animated gif:

In the animation, purple gas atoms start above the horizontal barrier in the middle of the box, and green atoms start below the barrier. As time progresses, the purple and green atoms end up spread throughout the entire box. This “spreading out”, in a physical sense, was claimed to be an example of the second law, yet I could never find what heat was being transferred in this example. If no heat is being transferred, the Clausius second law doesn’t apply; we are left with hand waving about disorder.

So is there a version of the second law that relates to concepts more general than heat and temperature? It turns out the answer is yes, but I had to wait many years before I learned it. Surprisingly, it turns out this more general second law isn’t really a principle of physics, but rather a principle of reasoning. This more general version of the second law not only explains why the Clausius version is true, but gives us a tool for much more general questions, like the evolution question or Muse’s economic musings. It also appears in everyday life, and not just in situations involving heat and temperature. For example, why is darts difficult? Why can’t most men sing operatic high Cs? And why are political polls (somewhat) accurate?

Uncertainty and volume

During my PhD studies, I became intensely interested in Bayesian statistics4 and how to use it in astronomical data analysis. During this process, I discovered the work of heterodox physicist E. T. Jaynes (1922–1998),5 whose clear-headed thinking and combative writing style changed the direction of my PhD project and my life.

One day I came across a particular Jaynes paper, which is now one of my favourite journal articles of all time.6 I didn’t understand it immediately, but had a strong sense that I should persist because it seemed important. Every so often, I’d return to re-read it, understanding just a little more each time. The breakthrough came after dinner one night.

I had taken out a tub of ice cream from the freezer for dessert. After dishing the ice cream into a bowl, I tried putting the tub back in the freezer, but it wouldn’t fit (due solely to my packing abilities). This got me thinking about volumes, and suddenly it clicked; Jaynes was explaining that the second law of thermodynamics, both the Clausius heat/temperature version and (importantly) a more general version, reduce to the principle that big things cannot fit into small spaces unless they are compressed. This is common sense when applied to physical objects, but to get the second law, you have to apply it to an abstract object: a volume of possibilities. This idea did not necessarily originate with Jaynes, as it can be found (albeit less explicitly stated) in the work of J. Willard Gibbs, among others. Another source that helped me understand was the posts of irreverant blogger “Pierre Laplace”.7

To demonstrate the idea of a volume of possibilities, consider the 52 books on my office bookshelf, 50 of which are non-fiction. [It’s a coincidence that there are 52 cards in a standard deck of cards. I try to avoid explanations involving cards, coin flipping, and dice, because people tend to (incorrectly) think they understand those already.]

Now I tell you that one of the books on the shelf was signed by the author. Which one? I’m not telling. Based solely on this information, it makes sense for you assign a probability of 1/52 to each of the books, describing how plausible you think it is for each book to be the signed one.

From this state of near-ignorance, it seems like you might not be able to draw any conclusions with a high confidence. But that’s an illusion; it depends on what questions you ask. Imagine if I were to ask you whether the signed book is a non-fiction book. If your probability is 1/52 for each book being the signed one, the probability the signed one is non-fiction must be 50/52 (adding the probabilities of the 50 non-fiction books together), or approximately 96%. That’s an impressive level of confidence — much more than you should have in the conclusion of a single peer-reviewed science paper! Of course, a high probability doesn’t mean the expected result is guaranteed. It just means it’s very plausible based on the information that you explicitly put into the calculation.

Here is a (very simple) diagram of my bookshelf, with the blue regions being non-fiction books, and the red being fiction: Clearly the safest bet is that the signed book is non-fiction, simply because there are more of them—they occupy a large majority of the volume of possibilities (which, in this case, corresponds to a physical volume on my bookshelf).

The general principle here, which Jaynes pointed out, is this: If you consider all possibilities that are consistent with the information you have, and the vast majority of those possibilities imply a certain outcome, then that outcome is very plausible. This is also a consequence of probability theory. The only way around this conclusion is to have some reason to assign highly non-uniform probabilities to the possibilities. For example, if I had some reason to think fiction books were more likely to be signed, I wouldn’t have assigned an equal probability of 1/52 to each book.

Clausius from Jaynes

The Jaynes version of the second law (about uncertainty) can be applied to all sorts of questions, and it can also explain why the Clausius version (about heat and temperature) is true.

When I say that I have a hot cup of coffee and that the air around it is cooler, it seems like quite a specific statement. But in a certain sense it is actually a very vague statement, in that it leaves out a large number of details about what’s actually happening. I didn’t tell you the colour of the mug, whether my window was open, whether the coffee was instant or not (usually instant with soy milk and two pills of sucralose if you’re wondering…I can handle the hate mail). More importantly, I also left out key details about the position and velocity (speed and direction of movement) of every molecule in the mug and the surrounding air. The high temperature of the coffee means its molecules are moving fairly rapidly, but there’s precious little information apart from that.

Based on this very vague information about the cup of coffee, can we predict what will happen in the future? Our common sense and experience say yes, very loudly. Hot cups of coffee cool down. Duh! But to a physicist the standard way of predicting the future is to use the laws of motion, which predict how particles (such as molecules of coffee and air) will move around. The catch is that we need to give the initial conditions: what are all the positions and velocities that we’re making our prediction from?

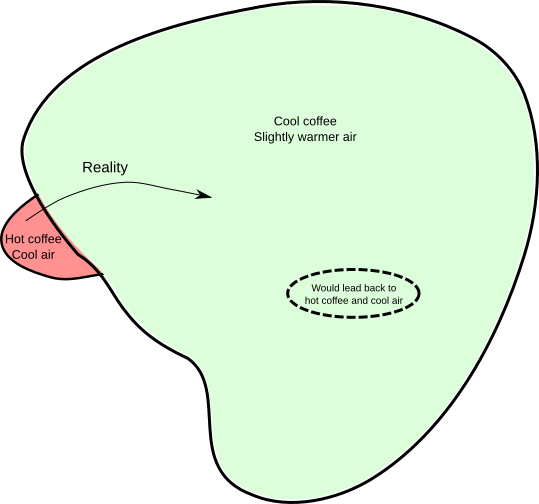

Since we don’t know the initial conditions (we only have the ‘vague’ information, specifically, the temperature), we can’t actually apply the standard laws of motion to see what will happen in the future. Any prediction we make will be a guess, or, more formally, a probability. We’re in a situation analogous to the bookshelf one. If we think of all possibilities for what the positions and velocities of the coffee and air molecules might be, the vague information we have can only restrict the possibilities down to a subset, shown as the red area below:

Now, what the laws of motion will do for you is tell you how a point in this diagram will move around over time (equivalently, how the positions and velocities of all the molecules will change over time). At a particular instant, the physical reality is represented by a single point somewhere in the red zone. As time goes on, that point will move around (as depicted by the curved arrow in the diagram). Where will it end up? That depends on precisely where in the red zone the point was initially. However, a special property of the laws of motion is that if your uncertainty about the initial point is represented by the red zone, then your uncertainty about where that point ends up will be represented by a region of the same volume. In physics, zones of uncertainty are like containers of ice cream; they can’t be compressed.

Notice that the red zone is much smaller than the green zone, representing the set of possibilities compatible with the vague statement, “The coffee is cool and the surroundings are slightly warmer (than they would be in the red zone)”. Therefore, if the red zone is moved around and changes in shape (but retains its volume), it’s possible for it to fit entirely within the green zone, simply because it’s smaller. On the diagram it’s about 20 times the area or so, but in physics it can be bigger by a factor of something like 10^(10^20). Therefore, the following rule of thumb is at least possible: if the starting position is in the red zone, the final position will be in the green zone.

The opposite situation doesn’t work. Instead, we have to admit that if the starting position is in the green zone, the final position will almost certainly not be in the red zone. Translated back into statements about coffee, ‘hot cups of coffee tend to cool down’ is a reasonable rule of thumb, but ‘cold cups of coffee in cool rooms tend to heat up’ is not, and this is all due to the volumes of the red and green regions in the set of possibilities.

There is a freaky subset of states within the green zone which would lead back to a hot coffee. But its volume is absurdly tiny that we could never hope to engineer a coffee/air system that’s actually in that subset. Thus, the idea of making a plausible guess based on your incomplete information explains why the thermodynamic ‘heat and temperature’ version of the second law is true. In fact, the connection is so close that Clausius’s definition of entropy corresponds exactly to the size of the regions of uncertainty.

Interestingly, this explanation doesn’t really explain anything about time, since notions of time were assumed in the explanation itself. Presumably, a more fundamental explanation for time would explain it in terms of some other concepts.

Entropy: it’s not what’s there, it’s what you know

Many physicists will happily talk about “the entropy of the universe” being low in the past, or how Stephen Hawking derived the formula for “the entropy of a black hole”.

These are probably correct and interesting results (I am not very familiar with all the details of them), but I have a nit to pick. Entropy is too subtle a concept to be taken for granted. Since the exact same physical system can have more than one entropy (depending on how we want to think about it), we should be totally explicit about how we are defining and using it.

In terms of the previous diagram, entropy is not a property of the arrow (which describes what actually happened) but a property of the red and green regions (describing uncertainty). Entropy describes what is known about a system, or how much information a vague statement provides (or would provide) about the system. There is no ‘true’ entropy that we could calculate even if we knew everything there was to be known!

What rules of thumb are we looking for? Different ones may exist, and we’ll find them by using different entropies. It all depends on what specific vague statements we are interested in. For example, we might want to see whether hot coffee tends to cool down, and in this case entropy will involve heat and temperature, or we might be interested in whether gas in one half of a box will tend to mix with the gas in the other half of the box (like in the animated gif). In that case, the entropy will have nothing to do with heat transfer, but rather how much of each type of gas is on either side of the barrier.

When people first hear that a “law of physics” can be derived as a prediction based on near-ignorance, their natural inclination is to worry that a prediction based on near-ignorance might be wrong. Of course it’s possible. However, when this occurs, it’s a good opportunity to learn. If 99.99999999999% of the possibilities would imply one outcome, and that outcome does not occur, you need to figure out why, and in doing so, you might discover something new.

Evolution and economics

It’s worth thinking about whether the second law really does forbid evolution by natural selection. We don’t need to get particularly technical with the concept of entropy in order to have a go at that. All we need to ask is whether it’s plausible that a population of self-replicating organisms will tend to improve their survival and reproductive fitness over time.

The answer is yes, provided the mutation rate is sufficiently low. And if the organisms reproduce sexually, the population’s average fitness will increase even faster.8 This isn’t the Clausius version of the second law, but an example of the Jaynes one: of all the possible deaths, reproduction events, and mutations that could plausibly occur, most would lead to an increase in the average fitness of the population. The probability that a populations’ fitness would decrease is low because, for that to happen, the organisms with worse genomes would have to be reproducing more than the ones with better genomes.

I’m not an economist, so I don’t know whether Muse are right about the economic consequences of the second law. The economic mainstream seems to think continued economic growth is plausible and desirable. Some dissenters exist, and occasionally they seem (to my uneducated mind) to have some good points, although some others just seem to be Malthusians with a desire to take up gardening.

The second law in everyday life

The probabilistic reasoning underlying the second law is also applicable to other fields. I like to apply it to singing, which is one of my favourite hobbies. About ten years ago, I decided to learn how to sing, since it seemed fun, and not having to carry an instrument around has its advantages. Back then I couldn’t sing very well and in particular I couldn’t sing above E4, the E just above middle C. This was frustrating but very common. Most men can’t sing along with high songs unless they transpose the melody down by an octave.

It turns out that singing high notes requires very specific conditions to be achieved in the larynx, regarding air pressure and so on. To get this right, you need to apply muscular effort in your torso in a particular way that singers traditionally call support.9 You also can’t be quiet unless you want a very gentle “falsetto” sound. The volume required is more than most people would intuitively feel is necessary. For example, I can’t (attempt to) sing high-pitched rock songs while my wife is in the same room because it hurts her ears (because it’s loud; regardless whether it’s good or bad…). Your choice of vowels is also more restricted than at low pitches.

All these specific conditions (loud volume, correct support, a vowel that works) must be met in order to sing a high note. And the reason it’s hard is the same reason it’s hard to hit a hole-in-one, or carry out any precise physical feat; of all the things we could do, most of them don’t lead to a successful good-sounding note (or an accurate golf shot). If (almost) all roads lead to Rome, it’s a good bet you’ll end up in Rome. The second law of thermodynamics is as simple as that.

Understanding its logic, and how it arises from uncertain reasoning (essentially little more than probability theory), is the key to extending its use outside of physics in a sensible way.

References

- Carroll, Sean. From eternity to here: the quest for the ultimate theory of time. Penguin, 2010.

- Muse. The 2nd Law: Unsustainable https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EFxdvn52As

- Dawkins, Richard. The blind watchmaker: Why the evidence of evolution reveals a universe without design. WW Norton & Company, 1986.

- The Great Statistical Schism. Quillette, 2015. https://quillette.com/2015/11/13/the-great-statistical-schism/

- http://bayes.wustl.edu/

- Jaynes, Edwin T. Gibbs vs Boltzmann entropies. American Journal of Physics 33.5 (1965): 391-398. http://bayes.wustl.edu/etj/articles/gibbs.vs.boltzmann.pdf

- http://www.bayesianphilosophy.com/

- David MacKay, Information Theory, Inference, and Learning Algorithms. Chapter 19. http://www.inference.phy.cam.ac.uk/mackay/itprnn/ps/265.280.pdf

- Sadolin, Cathrine, Complete Vocal Technique, Copenhagen 2012. ISBN 978-87-992436-7-9.