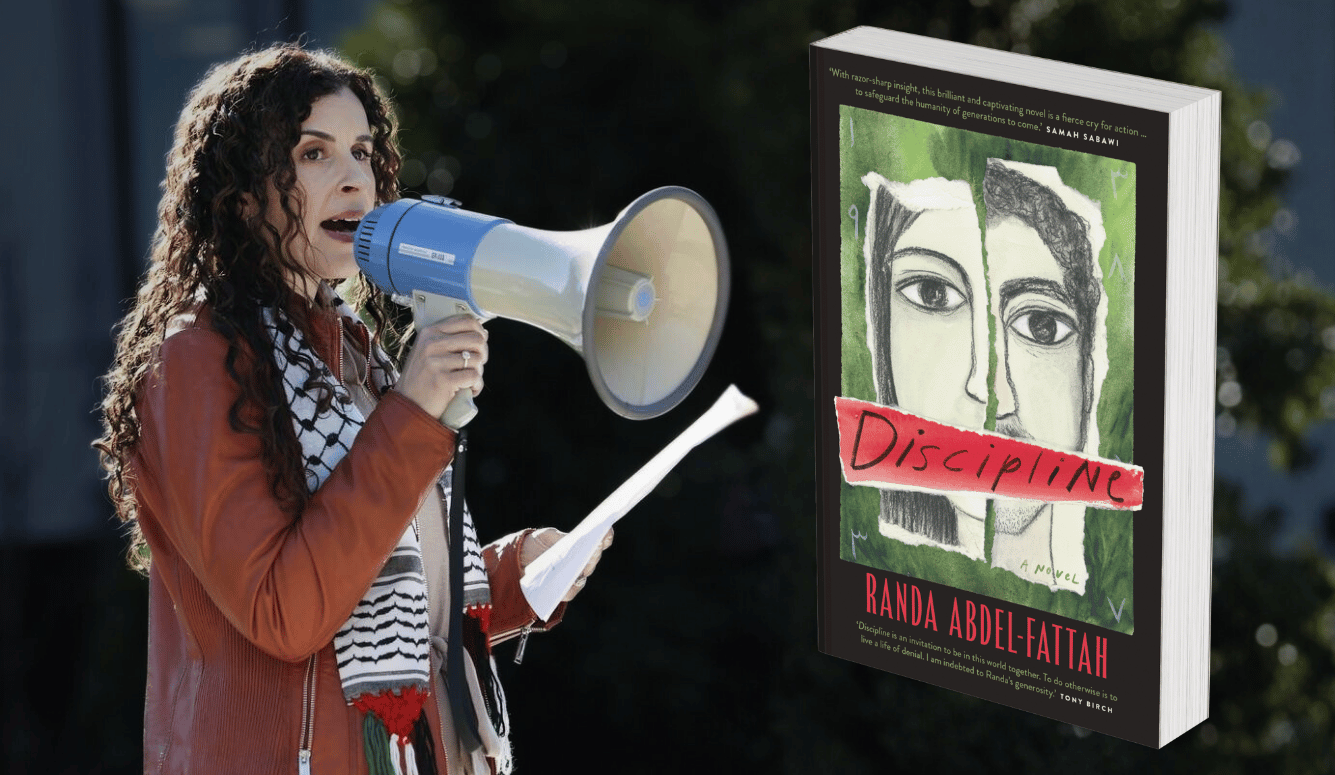

Art and Culture

The Paradox of Female Happiness

The decline in female subjective wellbeing was found to cut across both class and race and held true for women of all ages, with children and without.

Women are about 75 per cent more likely than men to report having recently suffered from depression. Women are also about 60 per cent more likely to report an anxiety disorder. These sharp discrepancies observed by Oxford professor Daniel Freeman, were found in eight of 12 nations from which statistics were taken. They also support a study which found that women reported higher levels of happiness than men in the 1960s but that this gender gap has now reversed. Why the change?

What does this mean when women are healthier, better educated, enjoy more economic freedom and more opportunities than we did 35 years ago? Since the 1960s it has become socially acceptable to leave unhappy marriages. The stigma that once existed around free expression of female sexuality has softened. Legislation is in place to protect women from sexual harassment. By many objective measures, women in the West have never been more liberated.

For all of this improvement many women are unhappy. Freeman, a clinical psychologist, noticed a gap in the literature on sex differences in mental health conditions and investigated national mental health surveys taken from the UK, US, Europe, Australia and New Zealand. He found that women are up to 40 per cent more likely than men to develop mental health disorders, with the sharpest discrepancies in depression and anxiety.