Blog

My Experience Working With Justin Trudeau: Quillette Cetera Episode 43

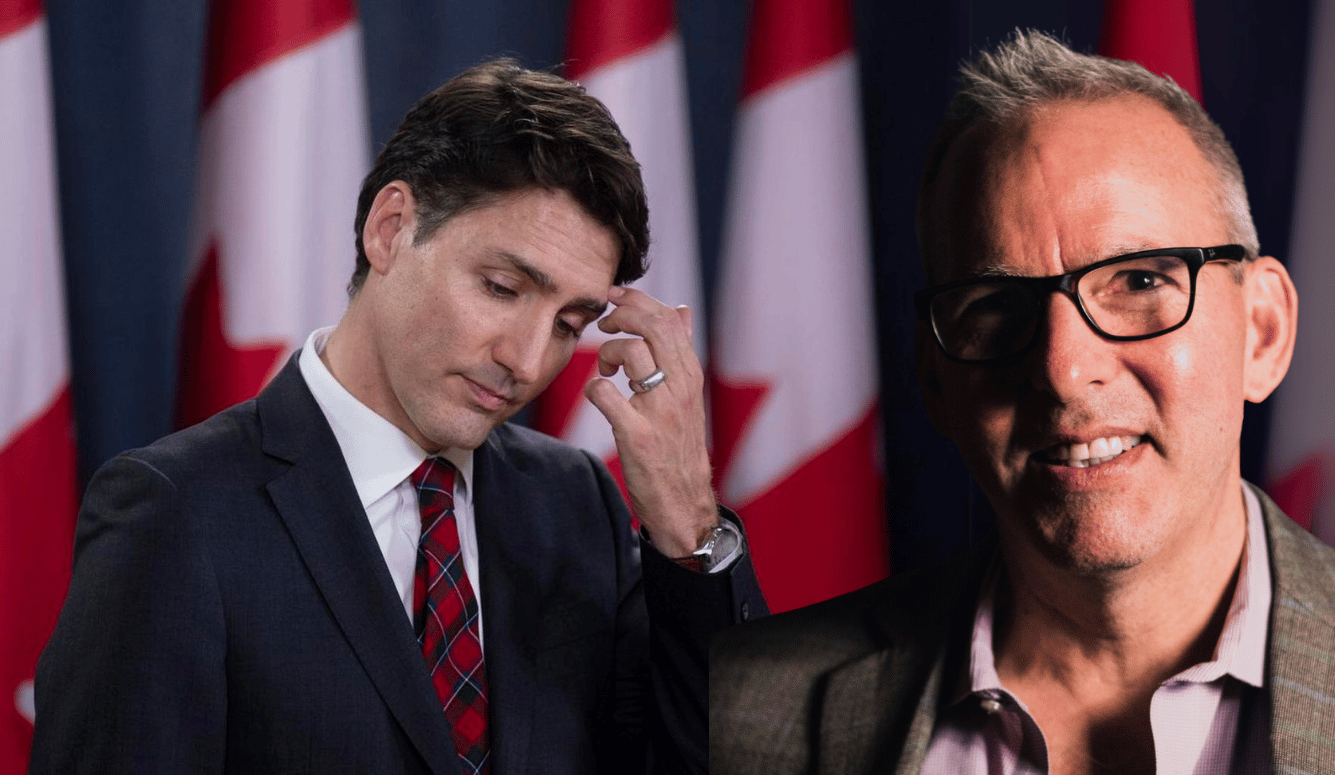

Zoe interviews her colleague Jonathan Kay, who once ghostwrote for Trudeau, about his time working with the Canadian soon-to-be ex-Prime Minister.

Quillette Senior Editor Jonathan Kay reflects on his time ghostwriting Justin Trudeau’s memoir and shares his take on Trudeau’s political trajectory—from golden boy to polariser-in-chief. We get into the highs of his early leadership, his pivot to hardcore social progressivism, the fallout from the truckers’ protest, and the growing anxiety around immigration. Kay also weighs in on the rise of Pierre Poilievre, the new conservative contender shaking up Canada’s political scene.

Zoe Booth: Maybe to start, Jon, could you explain a bit about your background? I didn’t know until I read your piece that you were asked to ghostwrite Trudeau’s memoir. So you know him quite well.

Jonathan Kay: Yeah, this takes us back to 2014 when you were about a wee lass. This was the year before Trudeau got elected as Prime Minister. He was already a big deal as leader of the Liberal Party. Canada’s political system is similar to Australia’s, so you get how all this parliamentary stuff works.

Explaining it to Americans is trickier. But like many politicians, he wanted to write a book that contextualised his life. In his case, there was a lot to explain because his dad, Pierre Trudeau, was a former Prime Minister. That gave him famous name recognition, but it also made him a target—especially for conservatives, who liked to frame him as a silver-spoon nepo baby.

Editorial assistant was the formal term in the publishing contract—ghostwriter isn’t used in those agreements. The liaison from Trudeau’s camp said they didn’t want a typical liberal fanboy perspective. They wanted someone who could push back during the editorial process, which I did because they wanted the book to appeal to a mainstream audience—not just Trudeau enthusiasts.