Quillette Cetera

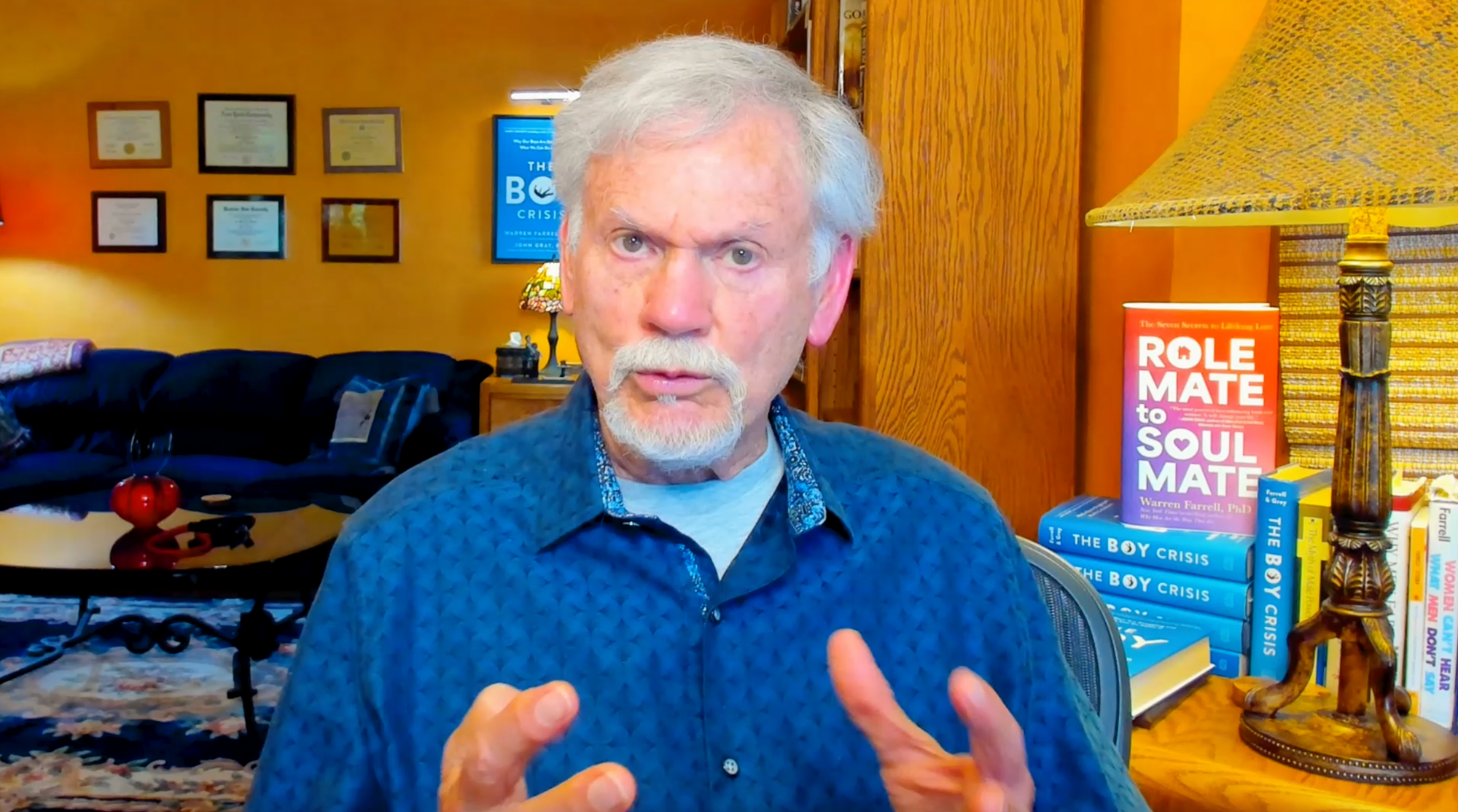

Rebalancing the Gender Narrative with Dr Warren Farrell: Quillette Cetera Episode 35

The couples therapist and men's rights activist discusses his new book and the current landscape of gender discourse.

Zoe Booth: Today I’m with Dr Warren Farrell, who you might know from the Jordan Peterson podcast or from the documentary, The Red Pill. That’s how I first came across him. I’m a massive fan of Dr Farrell’s work. He’s published multiple

books and is perhaps most famous for his book The Myth of Male Power, which challenged conventional views on gender and highlighted the often-overlooked

struggles faced by men. His other book, The Boy Crisis, was on a similar note, but more focused on boys. But his latest book, which we talk about, is called From Role Mate to Soul Mate. And it’s based on Dr Farrell’s years, decades of counselling couples and all of the wisdom that he’s come to gain from that. It’s all put in one book, it’s fantastic.

Dr Farrell is a former board member of the National Organisation for Women in New York City. This is where he hung out with the likes of Gloria Steinem and other prominent second-wave feminists. So he really cut his teeth in the feminist movement, however, he came to realise that there was more to gender issues than just women’s issues and that the feminist movement perhaps wasn’t focusing on men and men’s happiness as much as it should.

Dr Farrell’s accolades include being named one of the world’s top 100 thought leaders by the Financial Times and serving as a key advisor to both government

and educational institutions on gender-related politics. I really hope you enjoy this conversation and get a lot out of it. If you do, please share it with your friends and family.

OK, without much further ado, let’s get into the conversation.

ZB: Warren, today I wanted to start off with talking about something that’s really in the zeitgeist in Australia at the moment, and that is domestic violence. It seems like there’s been a spate of femicides lately. In particular, there was a quite notorious case of a schizophrenic man, Joel Cauchi, who went to a local shopping centre and stabbed a lot of people. Six people died. Five of those were women. And it does seem like he was targeting women. When journalists asked his father why Joel seemed to target women, his father said he wanted a girlfriend and he’s got no social skills, and he was frustrated out of his brains.

People—in particular, feminists—found this statement pretty offensive, like it was somehow excusing his behaviour. I guess I want to ask you: you’ve worked with so many men, so many women, so many couples, you’ve seen some of the darker sides of people—why is it that some men want to hurt women?

Warren Farrell: Well, first of all, that man put his finger right on it. When people are hurt, we usually respond by hurting the people who hurt us. Historically speaking and biologically speaking, when we were criticised or rejected, we felt that was a potential enemy. And so our biologically natural response to preserve ourselves was to get up our defences and to kill the enemy before the enemy kills us.

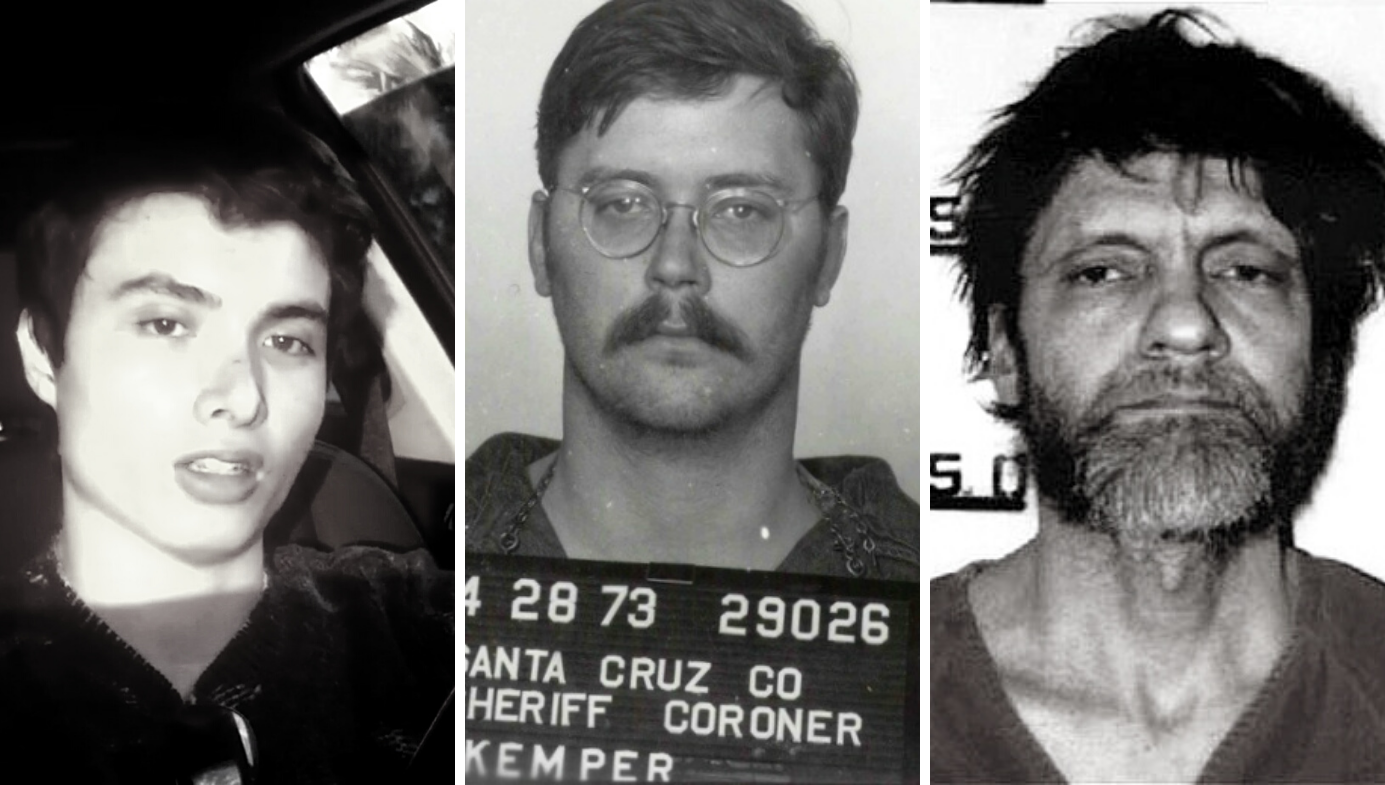

And we saw in the United States a fellow named Elliot Rogers some years ago at the University of California in Santa Barbara. He had been told by his parents that women liked gentle, caring men and sensitive men. And so he was gentle, caring, and sensitive, but he got rejected over and over and over again by women. And pretty soon he got angry. What was he angry at? On the surface, he was angry at the women. Underneath the surface, he was angry at himself for not being able to be acceptable enough and to always be rejected and to be a loser and to not know a way out of it because he had been taught that being sensitive and caring was what women wanted. But he felt that the women were choosing the men that were the strong men and the men that were sort of not taking no for an answer. And the guys that were sort of rough and tough. And that was exactly the opposite of the way that he was taught to be. But he took that out on the women because he felt like they were … basically, it’s not a rational thing. It felt like … he was being rejected and he was angry at that.

And we find the same thing in interpersonal relationships too, that for the same reason, when a woman and man love each other and they’re criticised by the person that they love, they don’t respond with, ‘My goodness, I hadn’t thought about that. Tell me more. I really want to know what’s bothering you.’ They respond in a biologically dysfunctional way that was functional to survive. That is, you get up your defences and you kill the criticiser before the criticiser kills you. But that was functional for survival. It’s just terribly dysfunctional for love. And it’s terribly dysfunctional for any human being to respond that way to real human beings because you really need to be able to look inside of yourself and be able to deal with what is not working and understand that if you do that, the chances are fairly good you will become less likely to be rejected.

ZB: That point about criticism and not handling it is perhaps one of the biggest nuggets of truth from your latest book, which we’re going to be talking more about in this episode. We know that it is men who tend to perpetrate more physical violence. I’d love to hear your thoughts about maybe the forms of violence that women engage in in relationships. But what can we do for men who are at that level where they physically want to hurt the women in their lives?

WF: Yes, first, it’s probably important to get the data correct on this. The women and men at every age, except for when they’re first dating, like teenagers, they are violent against each other about equally and on every level of violence. The work that’s been done in this area usually measures seven levels of violence, from slapping somebody to hitting/punching them, to hitting them with an object and to killing them. The one that’s most complicated is killing. I’ll get to that in a minute if you wish. But the levels of violence are, as they get more serious, women are more likely to hit a man with an object. Men are more likely to hit a woman, to slap a woman. But actually, I’m sorry, that’s not true. Even at that level of violence, women and men do it about equally, except in teenage years, where women are about four times more likely to hit their partner as the males are to hit the woman.

Now, whether that’s because these people are younger and this is more recent, I’m not sure.

But at any rate, the level of violence, female-to-male among younger dating people has gone up very significantly, female-to-male used to be more even. Now, the complex thing in the United States is that when you look at the people who kill, the people who kill are, theoretically, 50 percent more likely to be men killing women than women killing men. However, the way men and women kill is very different.

When men kill, they usually kill the woman in anger and then they usually kill themselves after that. So it’s extremely easy for the police to pick up the fact that the man killed the woman. But when women kill there is two different types of killing that women do. Wealthy women hire a hit man and the arrangement with the hit man is that they will split or get some percentage of the will that the man leaves behind if they succeed. But in order to succeed, they have to make it look like an accident, because otherwise the insurance will not pay out for the, quote, accidental death. So if the woman is poor, she will usually have a boyfriend and the boyfriend and she will make a plot to kill the man.

Now here’s the issue. This becomes a contract killing in either of those two types of killings. But contract killings are listed by the FBI as multiple-offender killings, not as the woman killing the man. There are many, many more contract killings than there are men killing women, but we don’t know what percentage of those contract killings are women killing men. We just know that a lot of them are, and we don’t even know what percentage are gotten away with, because the very purpose of a contract killing is to get away with it, to make it look like it. And sometimes, the police will, only after a woman has three or four men that she has killed, that they begin to become suspicious, and sometimes dig in her backyard and find a few men type of thing. So that’s the physical aspect of it. Women are much more likely to do reputation-ruining than men are and other forms of undermining of the man when they’re angry.

The important thing though is that both sexes, when they are criticised or they feel demeaned or belittled, both sexes feel pretty much exactly the same thing, that they feel angry. So imagine two people talking and one says to the other one, you know, “You’re never paying attention to me. It seems like you really don’t care at all.” And the other one says, “Wow, I’m so sorry. Tell me more about that. I certainly don’t want to, you’re the person I love more than anybody else in the world. Please tell me why you feel that way.” And then the person says, “Well, just look at dinner. You were reading a paper, and I was talking to you. Tell me what I said.” “Actually, I don’t remember what you said. I probably wasn’t paying attention to you, just like you said. Tell me what you were saying and how it must have felt to you to be ignored by me.” And I say, “I love you so much, but it doesn’t seem like I love you when you talk, when I don’t pay attention to you, does it?”

Now, is that woman likely to hit the man? I don’t think so, because she’s being, she’s feeling heard by him. But if he responds by saying, “Man, you talk about not paying attention to me. Look at how many times you haven’t paid attention to, you know what I mean, vice versa, look how many times you haven’t paid attention to me. And we were over at the Zimmerman’s the other day. And I said something and you… acknowledge you didn’t even remember what I said. How do you think that made me feel? You’re a lot worse about this than I am.” And she says, “No, you’re worse than I am.”

And then boom, boom, boom, boom, and it escalates and it escalates. And soon when somebody’s interrupted and yelled at, somebody might go and slap the other person. They might be very sorry afterwards. But when you don’t feel heard, you’re far more likely to escalate both verbally and physically. When you do feel heard, it’s unlikely that you will hit the person who’s hearing you well, as it would be for you to hit an ally.

ZB: Yes, and I would say maybe not only the feeling of not being heard, but the feeling of being trapped. In my experience, maybe I’m divulging too much, but the only times I’ve felt like I need to physically lash out has been when I haven’t—this is in previous relationships—haven’t been able to leave the situation that was obviously getting out of hand and defuse it by literally removing myself or I would have preferred that he left too, but it was always me who made the decision, “This is way too much, I’m going to leave.” And he would prevent me from leaving. And then I would feel very much like a caged animal that needed to... It felt like there was no other recourse but to physically lash out.

WF: Absolutely. You were mentioning that I just finished a book on this called From Role Mate to Soulmate, the one behind me.

ZB: Fantastic book.

WF: Thank you very much, it’ll be out next month in July. You received a PDF form, so you’re one of the very lucky people who have read it. But that’s based on 30 years of conducting couples’ communication workshops. And I started to see that in every workshop, people like John Gottman and other people said that they all shared the wisdom in workshops that it’s dysfunctional to become defensive when you’re criticised. But almost no one took that wisdom and applied it when the criticism came in real life at home. And so I started asking myself … what inspired me to start these workshops some 30 years ago was that I just challenged myself with, ‘Can you, Warren, invent a way to make this happen in real life?’ And I started to understand that this was not going to happen if you allowed criticism to happen spontaneously, because our gut-level heritage of responding defensively was so built within us.

So I created something called a caring and sharing experience, a caring and sharing practice, in which couples set aside two hours a week in which they first start appreciating each other and then they share just one concern that they built up during the week and then they finish by appreciating each other. But before they share their criticism, their partner has to alter their biologically natural state of responding defensively to criticism. And they do this with six, by meditating into six mindsets. One simple mindset would be what I call ‘the love guarantee.’ So you and your partner would sit down. And before you heard your partner’s criticism, you would say to yourself—what is your partner’s name, Zoë?

ZB: Jonathan.

WF: If I provide a safe space for Jonathan to say whatever he would like, in whatever way he would like, whether I agree with it or disagree with it, whether the tone of voice is too intense or not, if I provide a safe space for that, Jonathan will feel more safe with me, more heard by me, and therefore more loved by me, and therefore love me more. So you’re away from the intensity of the experience and you’re beginning, this is just one of six meditations, and then, in that meditative state, you say when you feel completely safe and secure to hear anything your partner needs to say. And without regard for whether it’s distorted or exaggerated or feel anger or sarcasm in the voice. Interestingly, when the partner knows that you’re really listening, there’s no need for sarcasm, anger, or distortion, but there will always be a different version of the world than you have.

Then your job afterwards, after doing the six meditations, is you’ll have a number of options. You’ll lose grasp of that at certain points. I teach people in the workshop to say, ‘Hold,’ so that they can put the conversation on hold for a moment and re-centre themselves. And then after the conversation is over, I reverse the process and then the person who’s been listening has a chance to share their own version of that experience. But before they share their own version of that experience, I teach them how to hear their partner’s experience when that partner’s experience is completely different from their experience, and then how to live with the conflicting versions of that experience, rather than try to argue the other person into agreeing with your version.

As you know, I give some illustrations in the book as to how to do that and why to do that. But then the next question becomes, what about the rest of the week? And the rest of the week I teach the couples how to do a conflict-free zone. When a criticism comes up, which—I’m not saying a criticism-free zone, because criticisms are likely to come up during the week, but how to take that criticism that comes up and be able to visualise being really heard that rather than you responding and having your partner respond to you and having the whole thing escalate, visualise that you have a response to that, it doesn’t agree with your partner’s response. And you can be 100 percent secure that if you bring up your response at that caring and sharing time, it will be heard.

So what do you want to do? Get into a big argument here or be fully heard at caring and sharing time? There’s a whole series of skill sets that I work with couples on to be able to create that conflict-free zone. For 30 years, I would invite all the people in my couples’ communication groups to follow-up phone calls in which they would tell me what mindsets worked for them really powerfully, what ones didn’t have much impact. And this was just a couple of about 23, what I call ‘love

enhancements.’ And I got feedback as to what worked and what didn’t work and kept eliminating and kept modifying and so on until I got the Role Mate to Soul Mate the way I wanted it.

ZB: Yeah, I think it’s an incredible guide for not only people who are in relationships, but also I can imagine it would be helpful for people who are not yet in a relationship or, you know, who are between relationships, maybe have just come out of a dysfunctional or unhappy relationship and want their next one to be a lot better and trying to prepare themselves to be a better partner and to have better expectations for what they want in a future partner and a future relationship. I think for people who have perhaps enjoyed the work of Esther Perel or Jordan Peterson as well, this book is 100 percent aligned with. It’s different, you’ve got your own take on things, but it’s in that same realm of just having healthier, happier relationships.

In your experience, how much of this comes down to simply compatibility? Is it true that some people just aren’t compatible?

WF: It certainly is true that some people are a lot less compatible than would be ideal for each other. Typically, you see this if you have to … somebody who’s a real strong personality and they fall in love with another, typically a successful woman will want a man who’s a successful man.

You’re often talking about two people who are very stubborn, very persistent. That’s one of the ways they became successful. The qualities it takes to be successful at work are in tension with the qualities that it takes to be successful in love. So when two successful people … which we can expand on, but those things are incompatibilities. But even people like that, when they understand how to hear someone else’s very strong, persistent perspective that leaves the person who is talking and trying to explain what they want to explain as not needing to be their worst selves, that is not needing to manipulate or logically figure out how to persuade the other person like they would at work.

And so they leave their spouse or their partner feeling much more able to be heard. We all have this extraordinary need to be heard. I’ll take this a step further. The final chapters of Role Mate to Soul Mate are called From Civil War to Civil Dialogue. I’m teaching couples how to take what they learned how to do with each other and apply it, let’s say, to... Let’s say your dad in a family has worked for years to have his daughter become the first daughter, the first person in the family to go to college. And the daughter comes home from college and says, for the first semester after the dad has, say, driven a cab for 70 hours a week for his life to be able to have this dream moment and it’s Thanksgiving or a big holiday and they’re around dinner and the dad draws the daughter out and says, “Well, what did you learn in college?” And the daughter says, “Well, I learned that men are part of a

patriarchal society that made rules to benefit men at the expense of women. And

that basically men like you, Dad, particularly because you’re a white man and

you’re older, you’re really more part of the oppressor class.” Can you imagine

how the average dad feels at that point?

So what I’m teaching the dad in that case to do is to be able to hear what his daughter is saying and draw his daughter out and be able to know how to create, take what he learned in the workshop and be able to basically meditate into an altered state before he hears the perspectives of his daughter, and really hear her for what her perspectives are. But then ideally to ask her to do some of the same for him. So there’s a number of things that I do like that, and I ask each person to work on finding a person’s virtue.

So maybe the virtue, maybe the daughter has now become a strong feminist

and the dad feels that women and men were really the best the way they were,

naturally different. So I’m asking the dad to say, “Let’s look at the virtues.”

Where did you start with your feeling that there was a value to feminism and

seeing that you wanted women to be empowered, that you wanted women to be

strong, you wanted women to be able to do what they wanted to do in the world?

And now this may have gotten taken to an extreme and become wokeism and cancel culture and DEI, but before you go to wokeism and cancel culture, go to the

virtue that your daughter started from and acknowledged her and talked to her

about how you agree with those virtues and be proud of yourself for having

taught your daughter to want to be empowered. And before you get to whether a

victim power is really empowering your daughter, a victim power is undermining

the power of your daughter and the respect for your daughter.

And so I’m teaching both parties in political situations, whether it’s your daughter or somebody at work or somebody from the completely opposite political party, conservative versus liberal, talk about: What do conservatives want to conserve? What do liberals want to, what do they feel is progress? and so on. You don’t have to agree, but you need to leave the other person knowing that you hear their virtues, what they started out with, their best intent. And that allows you to be friends even as you are different. At work, this is so important because you get a whiff of somebody’s feelings about a political candidate, and it may set you against him or her.

ZB: Why is that? Why does it hurt or feel like a personal attack at times that someone votes for a different political party or believes a completely different political opinion than you? Why does that cause so much strife in us?

WF: Because we feel that their fundamental values are different. For example, earlier in my career, I travelled all around the country and usually about 50 speaking engagements a year, mostly at colleges. I get out of the plane and oftentimes I was speaking on behalf of feminism at that time. And somebody, so this is very liberal and quote progressive. And so the person that would meet me at the gate would say, “Dr Farrell, before you go anywhere, I just want you to understand that this is probably the most conservative place you’ll ever speak at and just be aware of that.” Well, after I heard that 20 out of 50 times a year for about 10 years, I realised this is a very conservative country that we live in the United States, and that most people outside of the university communities and urban areas, they feel that men and men or women and women getting married, having sex, having sex in my days outside of marriage, no less having sex with each other, the same-sex people, and no less getting married, this is everything against the Bible and so on.

But the media, for the most part, was fairly in tune with wanting to move to the next step of having people be okay with getting married if they’re with the same sex. And so you’re having, on the one hand, people who believe in all these values from generation after generation. It’s part of their Bible, it’s part of their faith, it’s part of what they believe makes America great. And suddenly they’re hearing perspectives from the progressive left that are making them feel like less than, and they don’t feel that the media is talking from their perspectives.

And so after a while they begin to look for somebody magical, a snake-oil salesman like Trump to be able to get them out of that. They’re willing to accept any liar, narcissist, self-centred person in order to be able to be heard because they haven’t felt heard.

ZB: Wow. So it’s just so inherent to the human condition, I suppose, this need to feel heard, not only in romantic relationships, but in life. Yes, that’s very interesting. You know, you mentioned before this example of a young woman coming to complain to her dad about him being part of the patriarchy. It reminds me, I went through a similar situation when I was about 14 or 15. I got heavily into third-wave feminism. I can’t remember any specific situations of lecturing my dad, who I had and still have a fantastic relationship with, but I remember him never arguing with me. He just listened. And eventually I just, I guess, grew out of it. He had a lot of patience.

WF: Yeah, that is wonderful. That is really wonderful. Just listening is a great first step. Being able to not just listen, but also to articulate. I was using the Trump example in a negative way before, but let’s say you have the daughter who’s into cancel culture and woke and so on and doesn’t want anybody to speak who has different perspectives, rather than starting from the place of, “Freedom of speech is so important,” start from the place of, “I can see why you want people to be able, in your college education, to be able to hear that blacks have been treated badly and we need to compensate for that and help them get back on their feet again.” Before you get into the virtue that’s taken to the extreme that becomes the vice, which both left and right have, let your child, your friend, your colleague, a

political opponent know that you understand the virtue where they come from. It’s

a lot easier for them to hear you once they see that you see that.

ZB: On another topic, it’s a bit different, I suppose, but it’s similarly a topic that people get very upset about and have big debates over. It’s non-monogamy, which seems to be more and more popular, from what I see. I’m not sure. You know, I’m 29, I haven’t been on the planet for that long. The seventies looked pretty fun, it looks like there was a lot of polyamory happening then as well, but it does seem to be more accepted now.

Esther Perel talks about this too, about how, to expect everything just from one person is an unrealistic expectation to have. She has popularised exploring forms of non-monogamy. What do you think about this?

WF: It’s a trade-off. There’s also two really important dimensions of a person’s life. The trade-off is that with monogamy, you get stability, you get security, you get an ability to plan ahead with your partner, come closer to them because they are everything to you. You try to listen in multiple ways, to make compromises, to work things through. On the other hand, you don’t have the diversity, you don’t have the freedom. You often feel bored. You feel like you might be fantasising other partners and feel badly about that. That’s if you don’t have children.

So in brief on that first point, you have to be a much better communicator in order for polyamory or open marriages or open relationships to work. Because you really have to spend time listening to and dealing with your own jealousies. We are human beings. It doesn’t make logical sense to be jealous, it’s emotionally that way for the great majority of people. So that’s one part of it. The second part is if you have children. If you have children, the amount of time children take, the amount of dedication they take, the amount of communication is extremely difficult. Fathers and mothers have inherent ways of raising children that are very different. In The Boy Crisis book, I talk about chapters on the difference between dad-style parenting and mom-style parenting, which means there’s a need for communication about what is the value of dad-style parenting? What is the value of mom-style parenting?

There’s an enormous need once you have children for checks-and-balance parenting. But that takes a lot of time, and it takes time when you’re exhausted and overwhelmed. Both the mom and the dad, oftentimes the mom is just exhausted at every level from the moment she knows she’s pregnant to the time the children leave the home, basically. And the dad is oftentimes increasing his focus on work. And also, if he’s a good dad, when he isn’t working, spending time with the children. And that is very difficult to have a polyamorous relationship in the context of all those responsibilities to your children and the division of your mental, the division of yourself between thinking of your child, your spouse, and also thinking of the other person you might want to get in touch with and how you’re going to arrange it, and whether you want your wife or your husband to see this text. And even though you have an open relationship, it’s still … it creates pain. So I definitely advise monogamy when you have children. When you don’t have children, make sure you master the Role Mate to Soul Mate communication first before you get into any type of open relationship, if you don’t want the open relationship to undermine your primary relationship.

ZB: Great answer. Having this conversation with you, you’re so wise. You’ve got so much experience talking with couples. I wonder though, the couples who must be reading this book or coming to your workshops, they at least have the level of self-awareness to know that they want to be a better partner or have a better relationship. What about the people who aren’t even aware that they may be in these highly toxic volatile relationships. Maybe there are drugs involved. Maybe there’s extreme financial hardship. Maybe they’re from a lower socioeconomic class. Do these same guides apply for them, or what can happen from a government level?

WF: Well, a number of things. First of all, I took calculus in high school, I’ve used it, I think, zero times since. Whereas if I had had communication classes from first grade on in school as part of my education and learned how to hear people that differed from me and understood that the bullying and the bullied have a lot of similarities in their personality. They’re both insecure. They’re both wanting approval. They’re both wanting attention. They’re both wanting love. They’re both wanting to be respected.

When I was training to be a teacher in college, we went away for a retreat weekend and everybody talked, was encouraged to talk honestly about what they felt and saw in each other person in the group.

And for the first time in my life, I saw that the things that I was trying to present myself as that maybe weren’t 100 percent truthful, most people just saw right through me. And it was like, “My God, there’s something,” the importance of communication really started to come home to me. And yet when I was married, I was married once previously before meeting the woman who became my wife 30 years ago, I was good at articulating, but I used that to articulate a better argument from my perspective, which was not at all helpful in my wife feeling understood. And she was also very good … She was a top executive at one of the Fortune Top 50 companies. She was also very good at that.

So that was not helpful. Now, if the government can support education, training people to communicate when we’re in first and second grade, that needs to be part of our core curriculum. That’s number one.

Number two, socioeconomically poor people. One of the things that I did, one of the plans with the Role Mate to Soul Mate book is that during COVID, I did a workshop with two couples that was put online. Now I’m working to find the money to be able to distribute to every poor community in the United States and Canada and hopefully overseas, copies of this online video that any couple can use and be able to practise that at home and to distribute this to faith-based organisations, to high schools, to libraries, to boys’ clubs, so that in every community in a poor zip code, they will have access for free to this couples’ communication course. That’s, I hope, one of my contributions I can make in my life.

ZB: In your experience, have you seen a difference between socioeconomic classes, for lack of a better word, and the types of relationship issues they have?

WF: It definitely happens across the spectrum. Black people will often talk about how in very poor areas, and also white and Hispanic people as well, if somebody just shows a lack of respect for them, that’s a good enough reason to pull out a gun and then shoot them. The common denominator is when you’re criticised, you feel a lack of respect. The uncommon denominator is if you are very poor and uneducated, you often have very few ways of responding to that disrespect that is constructive.

ZB: Thank you. To be honest, this so far has been one of my favourite interviews I’ve done. What I have to do is, I have to be careful to not share too much about my personal life. I’m such an oversharer and I love talking about relationships and sex and everything. But that’s not quite ... perhaps our audience wouldn't like that.

WF: I would say that when people share from their personal life, it feels so much more real than when they don’t. And so I think your audience will appreciate that, particularly a conservative audience, because oftentimes conservative people are more conservative about their sharing of their personal life. And the more conservative they are, the more the invitation into that opens many doors for them.

ZB: That’s a good point. I hadn’t thought about that. But I have been told before that me putting myself out there and my vulnerabilities and things like that allows people... Actually, I’ve had a lot of men in my life tell me this, that I’m one of the only women they’ve felt comfortable divulging some of the darkest parts of themselves with. And that’s a massive compliment, I think.

WF: That really is a massive compliment. Here’s why it’s a massive compliment. Most men fear that when they open the dark side of themselves, or even their shadow side, that they will lose the respect of a woman. And when they lose the woman’s respect, they’ll lose her love, and when they lose her love, they’ll also lose

her sexuality. And so whether they want her for respect, love, or sexuality, they just feel that it’s not a safe place to open up that way.

ZB: Yeah, I can understand that and I think it’s very sad to hear that. I can’t imagine someone, regardless of their sex, sharing something vulnerable with me and me cutting them off and saying, “That’s really embarrassing,” or “You shouldn’t talk about that,” or “You’re a bit of a loser.” That’s a horrible way to treat anyone. And my issue with many things about modern feminism is that, why do we treat men like they’re not human? Men are human just as women are human. It’s not about constantly seeing everything through a lens of sex or gender. It’s just about seeing someone for their humanity. Males suffer, you know, they’re humans. Of course, I’m going to sympathise with human suffering, regardless of if they’re a man. It doesn’t detract from it.

WF: Absolutely. I talked to so many high school students here in the United States who say that. I remember once being filmed here in Mill Valley. And in the middle of the filming, a young man was walking by and was observing the film crew. And he seemed like he was in high school. I saw him being very curious. I explained to him what we were doing at the first break. And he said, “Wow, fascinating.” I said, “Are you in high school?” And he said, “Yes.” And I said, “Your energy feels like you’re heterosexual? Is that correct?” “Yes,” he said. I said, “What do you learn in school about men and women?” And he said, “That we men are part of the patriarchy and that we make rules to benefit men at the expense of women and that we’re the oppressors and that the future is female.” I mean, he didn’t go boom, boom, boom like that. But over a period of time, he said all that.

And I said, “Do you have a girlfriend?” He said, “Yes.” And I said, “Well, when you talk to your girlfriend about this, what does she say?” He said, “My God, I would never talk to my girlfriend about this. She’s a feminist. She would argue with me. She would have no respect for me. She would be just like … no, I don’t talk to her about it.” And I said, “Are you thinking about maybe possibly marrying her?” And he said, “Yeah, yeah, very possibly.” And I said, “Would you share this with her before you got married?” and there was silence like he never thought of that before. It was so deeply sad that you would think about marrying somebody and opening your heart, and life, and inner self to, which to me is part of marriage, a good marriage, and to feel these things about yourself that you’re having to keep inside of yourself for fear of being rejected, not loved, and not respected is such a curse, such a terrible, terrible thing to do.

ZB: Definitely. And I find it very strange that in so many ways, modern feminism is all about men being better and talking more and not having toxic masculinity and all this stuff. And then at the same time, there’s this laughing or mocking of men and there are these mugs that say ‘Male Tears’ and all this stuff and when people share a video of a guy crying online or even that video of Jordan Peterson crying, people were so quick to mock him, many supposed feminists. So, it’s like, ‘What do you want?’ On one hand, you say you want men to show their emotions and then you mock them when they do.

WF: Yes, yes, absolutely. Men feel caught between a rock and a hard place and they feel that their feelings are wanted when it’s in praise of women, but not wanted when it’s revealing some of the feelings that they have about female privilege, about women wanting to have their cake and eat it too, women being critical of men without looking introspectively at themselves, women focusing on victim power rather than sharing responsibility or talking about, ‘What responsibility do I have for this outcome?’ These are just a few of hundreds of things that lead to the reasons we have so many more males today committing suicide than females. When boys and girls are nine years old, they rarely commit suicide. And when they do, it’s about equal. But when they get to be the ages of between 10 and 14, boys commit suicide twice as often as girls. Between the ages of 15 and 19, four times as often. Between the ages of 20 and 25, five times as often. Most people don’t know that.

Yet, if this was reversed and the journey through growing up female led to women increasingly committing suicide, there wouldn’t be a person who wouldn’t know that. When men and women are over 85, men are 1,750 percent more likely to commit suicide than women are. If that figure was reversed, we would all know that. We look all around the world and the OECD of the UN studied the 56 largest developed nations and found that in every single one of the 56 largest developed nations boys were falling behind girls in almost every single academic subject and in most of the other 73 metrics that I talk about in The Boy Crisis book, and yet most people couldn’t name two or three of those things, maybe education, that they’re falling behind in.

It’s about the only thing that the average person could today understand. But it’s not just education, not just suicide, but it’s unemployment, it’s dropping out of high school, it’s not being able to handle themselves emotionally, being much more likely to be addicted to video games, to die from drug overdoses, and on and on and on. If we really are caring, if women are really caring, part of caring is to extend their compassion to men. But historically speaking and biologically speaking, the purpose of men was to protect women and in order to protect women and other men, we had to be willing to die and be disposable. It’s very difficult to be focused on compassion for somebody who you have an investment in for them to be willing to die in order to protect you. You’re caught between wanting them to be willing to risk their lives to protect you and wanting to care about them.

ZB: Yes, I definitely don’t envy men and the roles they have to play. I think, like

everything in many ways, it’s really good to be a man and in many ways, it’s

really good to be a woman. And we both need each other, and we both have

different inherent weaknesses but also benefits or privileges. But you mentioned before this victim power and it is true that victimhood is a currency now, or maybe you’ve seen it for a while.

We talked briefly about Camille Paglia and how we’re both fans of hers. Her concept of Amazonian feminism really changed the way I think and really brought me back into feminism, I suppose, but specifically this brand of feminism, which is not about victimhood, but about power. Because women do have a lot of inherent power. She also has some controversial opinions when it comes to consent, which is very topical in Australia right now as well.

I would love to chat to you about consent and your thoughts on it, because the orthodoxy today is that couples should be getting an enthusiastic yes before they engage in sexual activity. What do you think about this?

WF: Well, I definitely feel both partners should be consenting before there’s sex. You don’t just rape somebody. But on the other hand, once you’re in a relationship, there’s a broad spectrum of consent. But yet still, in my personal relationship with my wife, we’ve been together 30 years and if I’m reaching out toward her and I’m sensing that she’s tired, to me it’s just the right thing to do to just back off.

You know the signs of consent, but you may be in a relationship where sometimes you tell your partner, ‘When I feel tired, I want you to come on because sometimes you take responsibility for trying to get me through it and out the other side.’ And there’s a tension there that might really create more sexual energy than it would be if you just backed off. So you have to, that’s part of the communication process, what type of thing works for you, and where is the balance between doing something that might alienate for a while but turn you on in the long run because of the tension being resolved versus something that you just are really appreciative of your partner picking up subtle signs of not being interested and you don’t want to be pushed on that. All of these things come down to communication and the contracts you build between each other.

But when you’re with a stranger, when you’re with someone new... One of the things that’s really challenging for a guy is that, on the one hand, we learn that in the United States if there isn’t affirmative consent, that is, if before you hold a hand with a woman and you’re in college, you’re supposed to say to her, ‘May I hold your hand?’ And she’s supposed to say, ‘Yes.’ And when you take the virtue of consent to that degree, it becomes a type of vice because there is very little turn on. A much better approach to that is if a woman is taking a man’s hand or a man taking a woman’s hand, then you take the risk of taking that person’s hand. And if the person isn’t interested, they just maybe squeeze the hand for a second and let go.

There’s ways of doing it like that, but where the risk is taken. But most men feel caught between if they do something like ask the woman, ‘May I take your hand?,’ they’re thought of as a wimp. And if they don’t ask the woman if they can take your hand, they’re thought of as a sexual harasser, which, literally that is against the law in many states, including California, where I live.

If you’re in college and you reach over and you’re on a date with a woman and you reach out or you’re just talking to a woman and you reach out to take her hand, she’s allowed to call you a sexual harasser if you didn’t first ask for an affirmative consent. That misses the sexual excitement of risk-taking, the interest on the part of women in a man who’s willing to take a risk. And it also allows us to escape what we need to be doing and working with women in developing their sexuality, which is when you are out on that date, you feel free to take the risk.

And when you are, when a man is moving too quickly, don’t just say ‘Stop,’ but say, ‘When I’m interested, when and if I do become interested, I’m not interested now, but when and if I do become interested, I now know that you’re interested. So there’s no risk of rejection for me to reach out to you. So when I’m ready, if I’m ready, I will reach out to you, don’t reach out to me again unless I reach out to you.’ So we aren’t working with women in school to share the responsibility for risk-taking.

And then we wonder why women are very rarely the inventors, why women are very rarely the entrepreneurs. One of the best ways to plan to become a powerful woman and an entrepreneur is to learn how to share in responsibilities for taking risks in the sexual area when you’re in high school or whatever age you begin to become sexual or feel sexual and to take those risks of rejection rather than always saying, ‘I’ll let all the risks of rejection be taken by men,’ and then I’ll blame men when they do it too quickly and I’ll laugh at men when they don’t do it quickly enough.

ZB: That’s really interesting. So maybe a pathway to female entrepreneurship and success is to take more control sexually.

WF: Yes, and also when you’re not interested, say, ‘I’m not interested now, but I don’t want you to continue having to take the risks of rejection. I’ll take responsibility from here on in. And I’ll share that with you.’ That’s a win-win.

ZB: And as I tell my friends as well, both male and female, people aren’t mind readers, men aren’t mind readers. I usually tell female friends that, and I would tell my daughter, if I hopefully one day have one, that. You have to assume that boys will be interested in you sexually. You just have to assume that as a default. Don’t go in there naïve; go in there knowing that and only put yourself in situations where you feel comfortable saying ‘No’ or saying ‘Yes.’ But don’t put yourself in situations where you know that it could be sexual, and you know that you’re not going to feel empowered enough to say what you want because that’s a recipe for disaster.

WF: Yes, indeed. So first of all, the first part of what you said, I want to validate that. You need to know that what’s happening in ninth, tenth grade in the class, that almost every boy that’s heterosexual in the class is interested in being sexual with about at least half of the women, probably two thirds of the women in that class. And what did it take for him to be sexual? About five minutes of time or less. That is just the way the biology of that interaction is.

So what does a woman want? If she’s beautiful, she takes that for granted. If she’s not beautiful, she is wishing she was beautiful enough to be in that category but doesn’t really want to think of herself as being in that category. So, because she doesn’t want to think of it as directly sexual, but so many women are spending a great deal of time trying to get in the right clothes, the right make-up, the right fashion, the right time to be attractive to the guy that she wants to be attractive to, but she doesn’t want to be approached by the guy that she’s not attracted to. It’s a dynamic that we all have to be aware this is what is happening in school now.

Another dimension of that is to understand that women are competing to have this beauty power. But they then oftentimes feel angry when it’s exercised, when the response to that beauty power is exercised by somebody that they’re not interested in. The beauty power is really there to have every man that she might be interested in interested in her, to have her first-choice men interested in her and even compete for her. But that leaves out … that leaves a challenging relationship for all the men she’s not interested in who are also attracted to her.

ZB: Yes. I find this concept of intrasexual competition—in particular, female intrasexual competition—so interesting. I could talk about it till the cows come home. Maybe we should save it for a future interview. I know I’ve taken up a bit of your time now, but to finish up, where can people buy your books? Where can they see you speak next?

WF: Yes, The Boy Crisis book you can just buy online and not just in print form, but also in audible form. And that’s available now.

The Role Mate to Soul Mate book is available in a number of ways. It’ll be available in July in both print form and audible form. But also at the end of that book is a QR code to get for half price the Role Mate to Soul Mate online video. I’ve made that cheaper to buy if you buy the book. So, you could buy the book and then get the online video for significantly less money than you could for just getting the video alone because I’m such a strong believer in the online video being useful for couples to actually do the experiences together in a way that makes it very easy to follow through the video version of it.

ZB: Great. And you’ll be speaking at ARC in London, is that true?

WF: In London in February, I’ll be speaking at ARC, which is the Alliance for Responsible Citizenship. Yes. And a number of other places, especially when the Role Mate to Soul Mate book comes out in July, I’ll be doing a lot of speaking and TV shows and so on.

ZB: So head to Warren’s website for more information about his upcoming speaking events. Dr Farrell, thank you so much for speaking to me today. I’m a massive fan of your work, I hope it comes through in this video. It’s been a pleasure to just have you there as a source of wisdom. I think the world really needs you right now. Thank you for joining me.

WF: Thank you. It’s been a pleasure. As I mentioned off camera, you just are a really good asker of questions. You’re thoughtful. You listen really well. It’s a total pleasure being interviewed by you.