Politics

Capitalism’s Paradox

Why prosperity breeds guilt, how status incentives reward critique, and what happens when function is replaced by moral performance.

In some of the most beautiful and prosperous places in America, a curious paradox has taken hold: the people who benefit most from capitalism increasingly appear to resent it. They live in high-amenity cities and mountain towns with preserved open space, reliable infrastructure, advanced healthcare, abundant leisure, and the freedom to choose where and how they live. These conditions did not arise spontaneously. They are the cumulative result of markets, private investment, innovation, and long-term economic growth. Yet in these same environments, it has become socially fashionable to describe capitalism as immoral, exploitative, or fundamentally broken. This is often dismissed as hypocrisy. That framing is too simple. What we are witnessing is not merely individual inconsistency, but a structural paradox produced by success itself. Capitalism generates abundance, and abundance reshapes human priorities.

When societies struggle to meet basic needs, economic systems are judged primarily on whether they function. People care about jobs, food, shelter, safety, and stability. Once those needs are broadly met, attention shifts. People begin asking different questions. Is the system fair? Is it humane? Does it align with my values? Does my comfort come at someone else’s expense? Capitalism excels at producing goods, services, innovation, and choice. It is far less adept at providing moral reassurance. It is impersonal. It distributes rewards unevenly. It does not explain itself or justify outcomes. It simply operates. For people whose material lives are secure, this impersonality can feel unsatisfying and even unsettling. Comfort creates space for moral inquiry, but it also creates moral anxiety. As scarcity recedes from daily experience, gratitude often gives way to guilt.

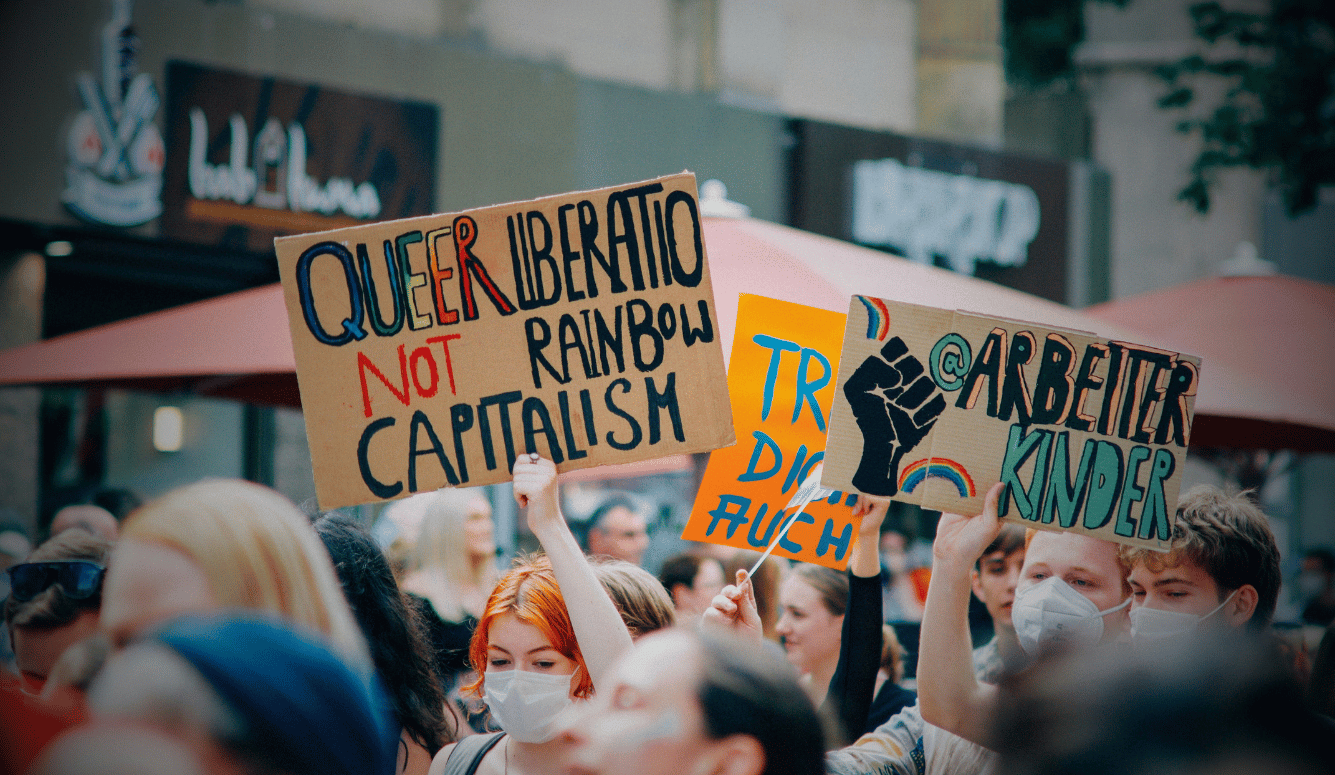

Many of capitalism’s noisiest critics live comfortably within it. They own assets. They benefit from property appreciation. They enjoy professional mobility. They have access to education, healthcare, and travel. Their material security allows them to focus on abstract harms rather than concrete tradeoffs. But this security produces a subtle psychological tension. It is difficult to reconcile personal comfort with awareness of inequality, luck, timing, or inherited advantage. One response is humility and gratitude. Another is guilt. A third is ideological reframing. Rather than saying, “I have done well in this system and feel conflicted about it,” it becomes easier to say, “The system itself is immoral.” This externalises discomfort. Personal unease is converted into ethical opposition. The system, rather than circumstance, becomes the culprit. Critiquing capitalism, then, serves a dual purpose. It relieves guilt and signals moral seriousness.