development

How Not to Develop a Country

The idea that we should redistribute wealth by fiat from prosperous to low-income and stagnating countries remains popular even though it is profoundly misguided.

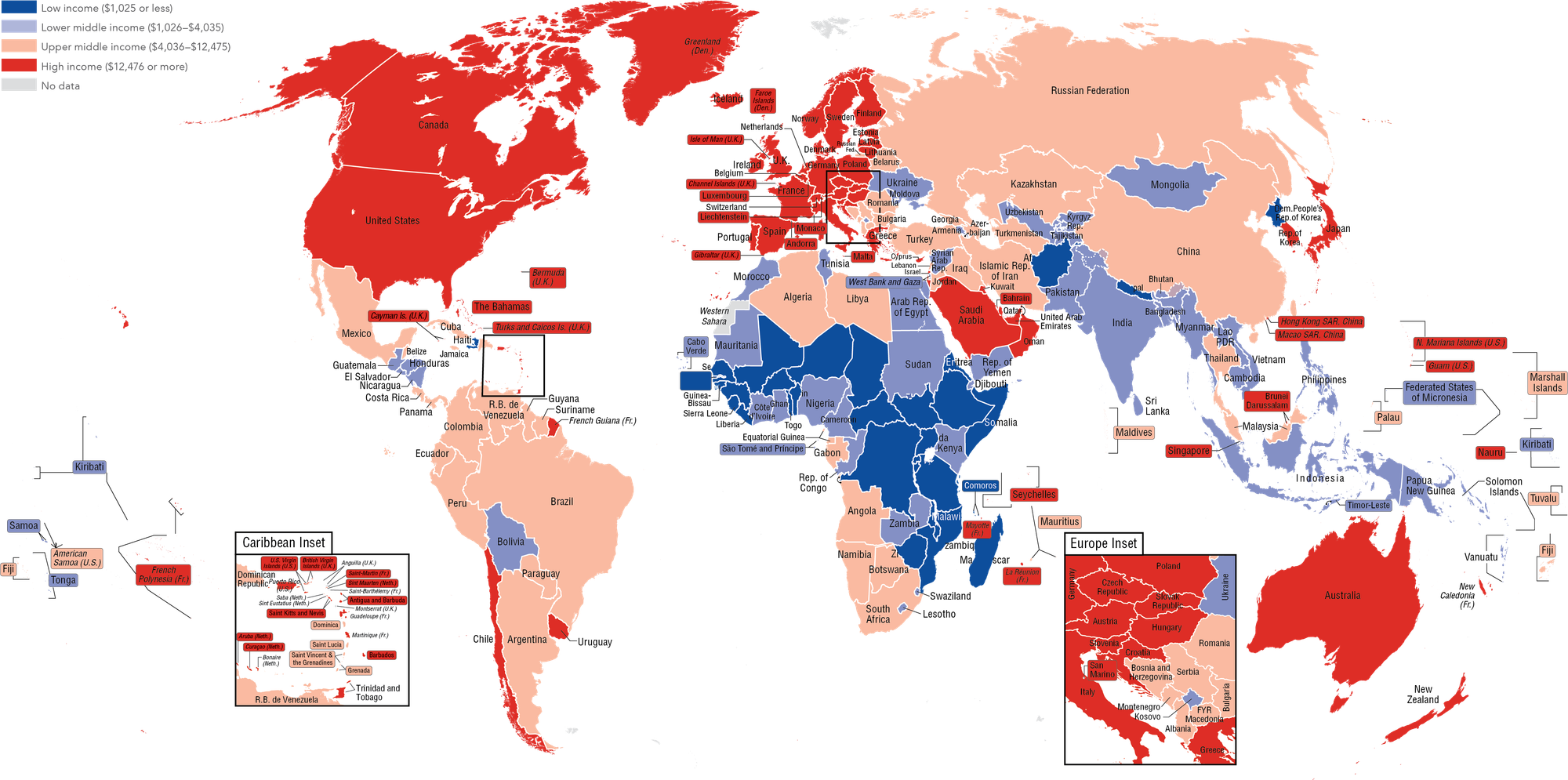

There are roughly 195 countries in the world, depending on how one counts. According to the World Bank, 87 qualify as “high-income economies,” with a per capita GDP above US$14,000. These countries account for only around 1.5 billion people out of a global population exceeding 8.2 billion.

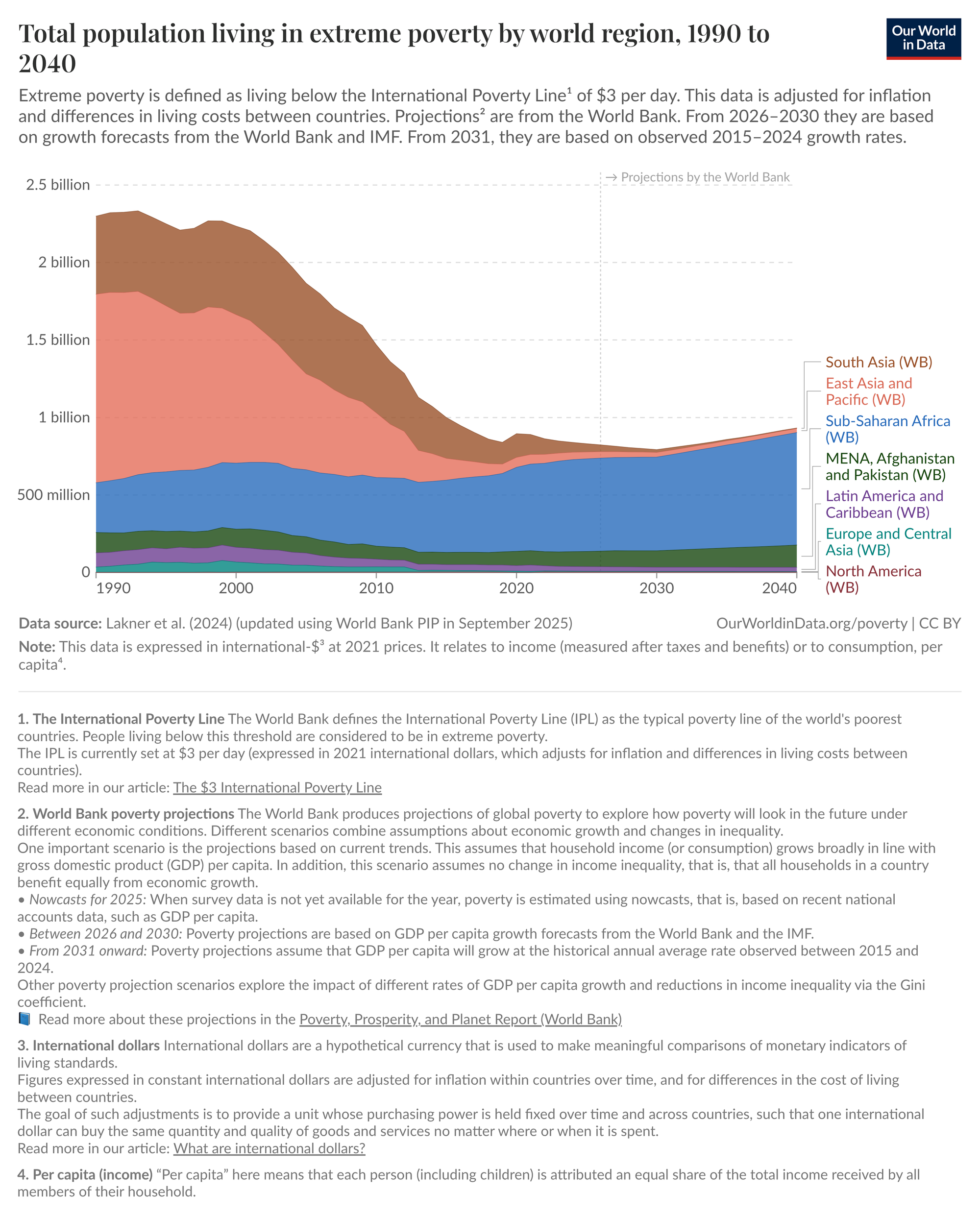

That figure, however, is about to rise dramatically. China’s per capita income currently hovers around US$13,000. Once it crosses that line, the number of people living in rich countries will jump to around three billion. India may follow in two decades if it can sustain its current unusually high growth for a prolonged period, potentially raising the figure to 4.5 billion. Even in that optimistic scenario, however, billions will remain impoverished, and they will be concentrated overwhelmingly in Sub-Saharan Africa. Over the past thirty years, global extreme poverty has declined sharply, but this is not because the poorest countries have become slightly richer, but because in 1990, most of the world’s poor lived in countries like China, India, and Vietnam, which later experienced sustained growth.

Today, by contrast, extreme poverty is concentrated in economies that have stagnated for decades. In countries such as Burundi, Mozambique, Madagascar, and the Democratic Republic of Congo, population has outpaced income, leaving poverty rates stubbornly high. Redistribution cannot solve this problem. When average income falls below the poverty line, equal division only leaves everyone poor. On current trends, global economic growth is likely to stall, leaving hundreds of millions trapped in extreme poverty.

No country in mainland Africa is currently classified as high-income. The only African nation to enjoy that classification is Seychelles—an island economy with unusual geographic and institutional features. Unfortunately, many African countries remain trapped in cycles of civil conflict, ethnic fragmentation, and resource dependence from which escape has proven exceptionally difficult. Meanwhile, most high-income countries fall into one of four groups: Western economies, East Asian economies, hydrocarbon exporters in the Gulf, and Israel.

The central question of development economics is how countries that are still poor can achieve sustained prosperity, and what stands in their way. Economists like Daron Acemoglu and Esther Duflo have devoted their careers to explaining why some countries grow rich while others do not, yet there is no settled consensus among economists on the relative roles of institutions, geography, culture, human capital, and historical contingency.

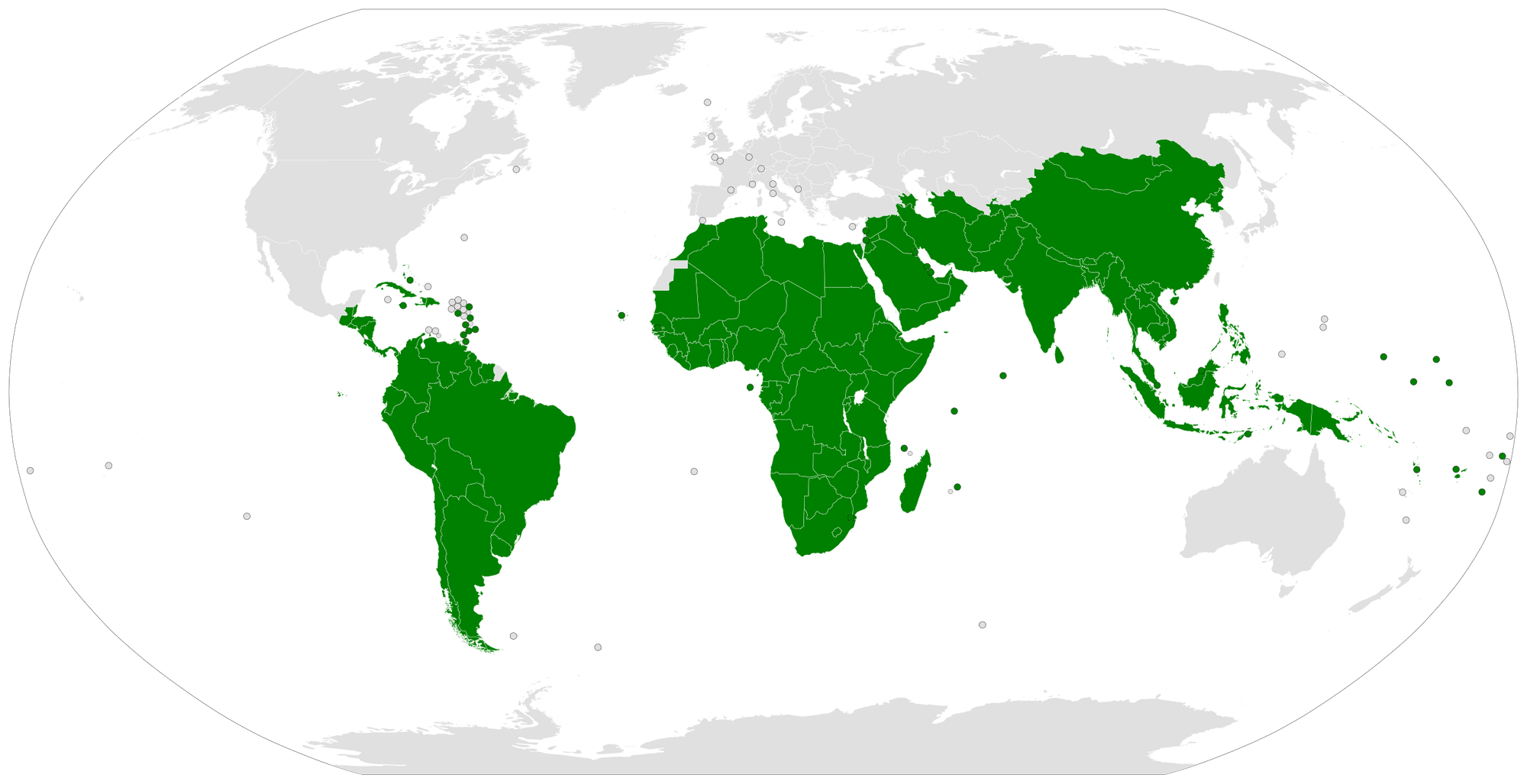

However, the Group of 77 (G77), an intergovernmental coalition of developing countries within the United Nations, advanced a simplistic but politically resonant claim: that underdevelopment is primarily the result of an unfair global economic order. That belief found its most ambitious expression in the New International Economic Order (NIEO).

The G77 emerged in 1964 at the first United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Initially a coalition of 77 developing countries seeking coordinated bargaining power, it has since expanded to over 130 members. Today, it includes nearly every country outside the developed world. The members of the original G77 shared a set of concrete economic grievances that shaped their view of the international order. Many were heavily dependent on commodity exports and were therefore exposed to extreme price volatility. Sudden commodity price collapses routinely wiped out their export earnings, destabilising their public finances and constraining their access to foreign exchange.

At the same time, these countries were affected by a long-term decline in the share of primary commodities in global trade and a corresponding rise in manufactured and industrial goods. To many G77 governments, this shift appeared less like an organic transformation of the global economy and more like a continuation of economic hierarchy by other means, transferring value from raw-material exporters in the developing world to industrial producers in advanced economies.

The Kennedy round of negotiations (1964–67) under the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) significantly reduced tariffs on manufactured goods, which benefited industrialised economies, while many commodity exports continued to face barriers. Even when formal tariffs were reduced, developed countries frequently relied on quotas and sector-specific protections to shield politically sensitive industries. Textiles provided a particularly stark example: although their labour-intensive production should have favoured poorer countries with abundant low-cost labour, agreements negotiated under GATT imposed quotas and restrictions, most notably by the United States, that severely limited developing countries’ access to these markets.

G77 members also argued that access to technology was essential for development. They expected advanced economies to help them develop technologically through concessional finance and development-bank lending.