Kurds

“No Friends but the Mountains”

America and the West have once again betrayed their Kurdish allies. Al-Sharaa’s assault on the Kurds of northern Syria, with Turkish backing, is just the latest chapter in the Kurds’ long struggle for self-rule.

Last month, the United States tacitly assented to the assault of the Syrian army, backed by Turkey, on the Syrian Kurdish autonomous zone known as the Democratic Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (DAANES). The assault, which resulted in the retreat of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF)—the Syrian Kurds’ militia—and the substantial contraction of the Kurdish-controlled zone, passed largely under the radar of the Western media, which are preoccupied with the crisis in Iran, the Russian attacks on Ukraine, and the unfolding second stage of Trump’s peace plan for Gaza. Western European governments ignored the event, underlining the by now traditional disinterest in the fate of the Kurds.

Syria’s Kurds have been US allies since October 2014, when Kurdish fighters began helping American special forces and aerial units combat ISIS, after the terrorist group conquered large swaths of Iraq and Syria. Over the following decade, American troops stationed in northern Syria continued to support the Syrian Democratic Forces in combating ISIS, while the SDF set up and policed large detention centres for captured ISIS fighters and their dependents. Complementing the anti-ISIS US–SDF partnership in Syria, there was a parallel anti-ISIS US–Kurdish military alliance in Iraq, where the autonomous Kurdistan Regional Government has ruled the north of the country since 1992.

The Kurds, who number 30–45 million, are an Iranic Sunni Muslim people living mainly in southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, northern Iraq, and northeast Syria, with significant diaspora communities in Germany and points west. Kurds speak Kurdish, a northwestern Iranian language, as well as the languages of the countries they live in, mainly Turkish, Persian, and Arabic. Since the second half of the nineteenth century, Kurdish tribal leaders and intellectuals have promoted the idea of Kurdish independence and the establishment of a sovereign Kurdish state, and in 1920 the victorious World War One Allies and the defeated Ottoman Empire signed the Treaty of Sèvres, which provided for the emergence of such a state, encompassing much of the territory the Kurds inhabited, which was to be first autonomous and then—subject to League of Nations approval—independent.

The Kurds, who number 30–45 million, are an Iranic Sunni Muslim people living mainly in southeastern Turkey, northwestern Iran, northern Iraq, and northeast Syria, with significant diaspora communities in Germany and points west. Kurds speak Kurdish, a northwestern Iranian language, as well as the languages of the countries they live in, mainly Turkish, Persian, and Arabic. Since the second half of the nineteenth century, Kurdish tribal leaders and intellectuals have promoted the idea of Kurdish independence and the establishment of a sovereign Kurdish state, and in 1920 the victorious World War One Allies and the defeated Ottoman Empire signed the Treaty of Sèvres, which provided for the emergence of such a state, encompassing much of the territory the Kurds inhabited, which was to be first autonomous and then—subject to League of Nations approval—independent.

But with the resurgence of Turkish power under Mustafa Kemal (“Ataturk”) in the early 1920s, the Western democracies withdrew their support for Kurdish statehood and, ever since, the Kurdish minorities in the Middle East have been systematically oppressed, especially in Turkey and Iraq. The assault on the Kurds in northern Syria is just the latest chapter in this history.

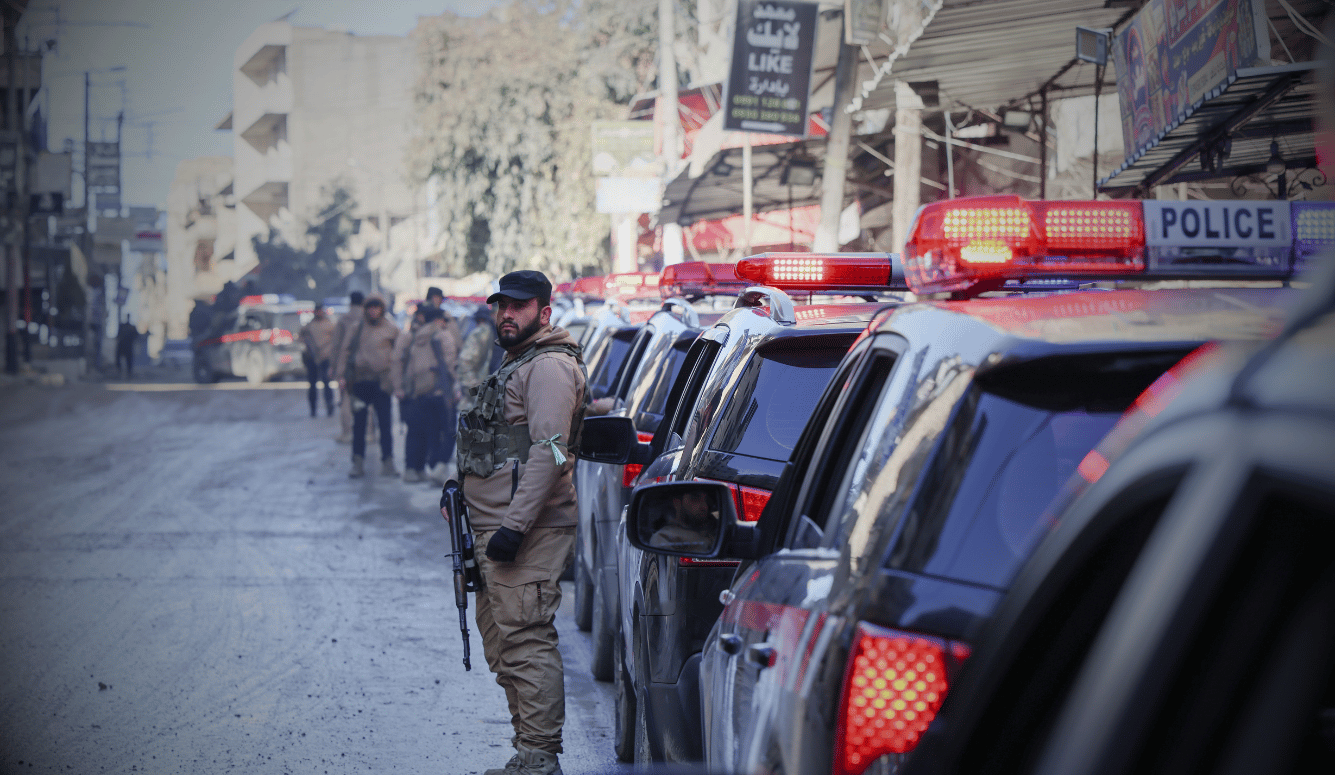

The SDF has now been confined to two small enclaves around the Kurdish-majority towns of Qamishli and Hasakeh at the northeastern tip of Syria and around Kobane, a hundred or so kilometres to the west. Both these areas border on hostile Turkey to the north. In their sweep eastward and northward, the newborn Syrian national army mustered by the country’s Islamist president Ahmed al-Sharaa, together with its Islamist militia and Arab tribal allies, captured the largely Arab towns of Raqqa and Deir ez-Zor—sites of the Turkish massacre of Armenians during the genocide of 1915–16—as well as the Conoco gas and Omar oil fields, economic mainstays of the Kurdish autonomous zone.

They also took over the al-Hol and Roj detention camps, which house some 24–26,000 ISIS dependents, sixty percent of whom were children, together with a number of prisons at Shadadi and al-Aqtan, which held around 9,000 captured ISIS combatants. Hundreds of prisoners reportedly escaped or were let out by al-Sharaa’s forces, most of whom likely regarded the ISIS fighters as their Islamist brothers. American troops are currently busing at least some of the ISIS PoWs to detention centres in Iraqi Kurdistan. But the fates of the remaining detainees and of their tens of thousands of dependents—wives and children of ISIS fighters, who hail from dozens of Asian, African, and European states and whom nobody wants—remain unclear. It is likely that al-Sharaa’s government will free them, and perhaps even incorporate some of them into the Syrian army.

The assault on the Syrian Kurds was supported—if not actually orchestrated—by Turkey, which supplied the assailants with intelligence, logistics, and weaponry, including drones. Turkey is led by Islamist president Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who supported al-Sharaa and his troops in Idlib in northwestern Syria during the country’s civil war of 2011–24 and orchestrated last December’s offensive, which ended in the conquest of Damascus and the fall of the tyrannical Assad regime that had ruled Syria since the early 1970s.