Australia

Australia and the Clash of Worlds

The convicts and soldiers who arrived in January 1788 had not just traversed a vast distance across the oceans; they had effectively journeyed back in time.

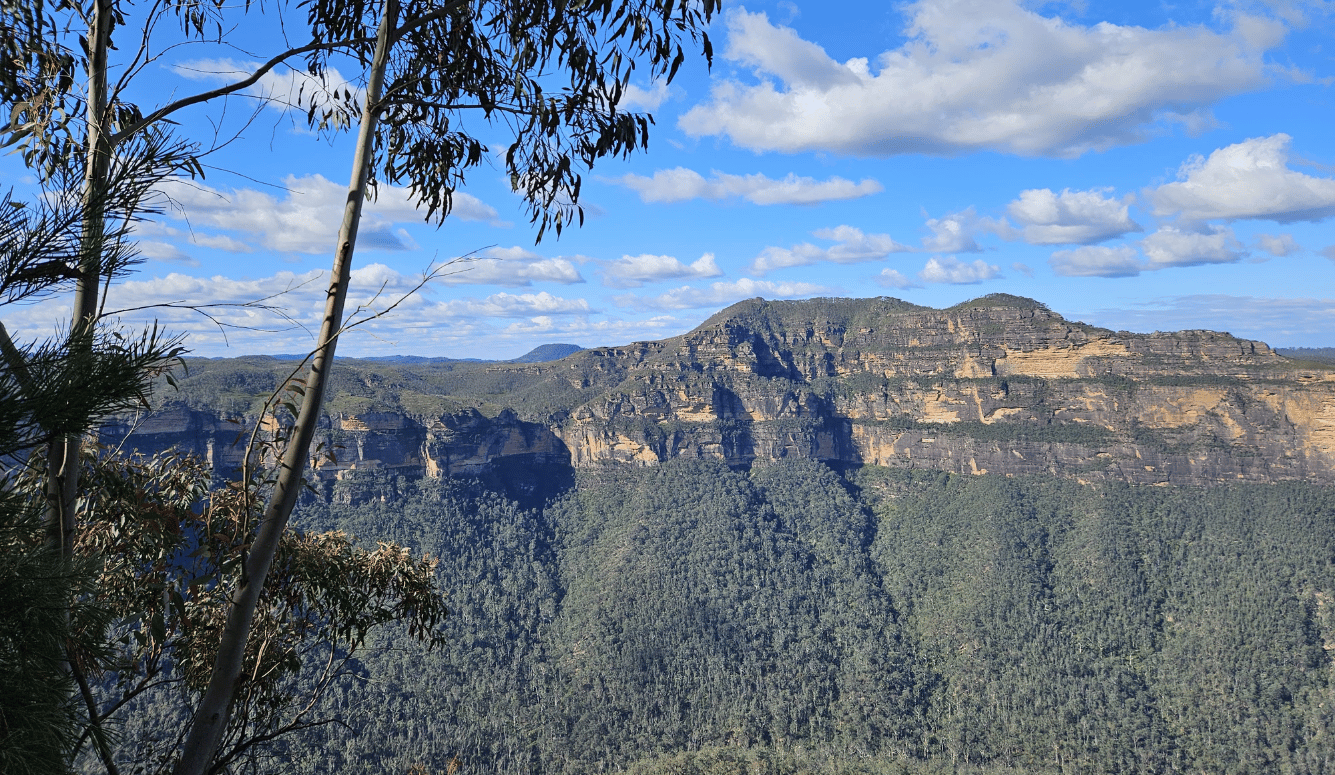

Australia has an extraordinary history. For 50,000 years, the inhabitants of this vast island remained largely isolated from the rest of humanity, living as human beings had lived for aeons, in small tribes of semi-nomadic hunter-gatherers.

There was some contact with the world outside Australia, of course, even before the Europeans first encountered this landmass. Over the millennia, a small trickle of outsiders crossed the Torres Strait—at first, walking over a land bridge and wading through shallow waters; later, leapfrogging across an archipelago of islands; and still later, after the Earth warmed and the waters rose, in small boats. The newcomers brought dingoes and perhaps a few primitive technologies: spear-throwers and certain designs in hafted weapons. Later, the Macassans would sail over from their Indonesian island each year to fish the sea cucumbers out of Australia’s balmy northern waters. Still later, a few Dutch and British sailing ships spied the coast and a few ran aground on rocky islands and inlets. But none of these visitors stayed.

Like all early peoples, the inhabitants of Australians were deeply conservative. They invested the landscape surrounding them with myth and legend; they gave their lives meaning through stories and taboos. Despite this, these were not lives of unremitting hardship—on the temperate southeastern coasts, in particular, fish, eggs, and birds were plentiful and good eating, alongside goannas and kangaroos. But the raw materials they had to work with were sparse—they had no domesticable animals, no easily cultivable plants. As a result, life remained fixed, unchanging; cut off from the dramatic developments that followed from the agrarian and industrial revolutions, the people here must have had little idea of how profoundly we human beings can transform our world.

The convicts and soldiers who arrived in January 1788 had not just traversed a vast distance across the oceans; they had effectively journeyed back in time. They created a deep gash in Australian history. And, as any good sci fi buff knows, when you disrupt the timeline in that way, the consequences can rip the fabric of reality. Where other countries gently eased into modernity, century by century, in slow increments and “revolutions” that often lasted centuries, in Australia two systems collided. We are still feeling the aftershocks of that collision.