Australian History

A Lucky History

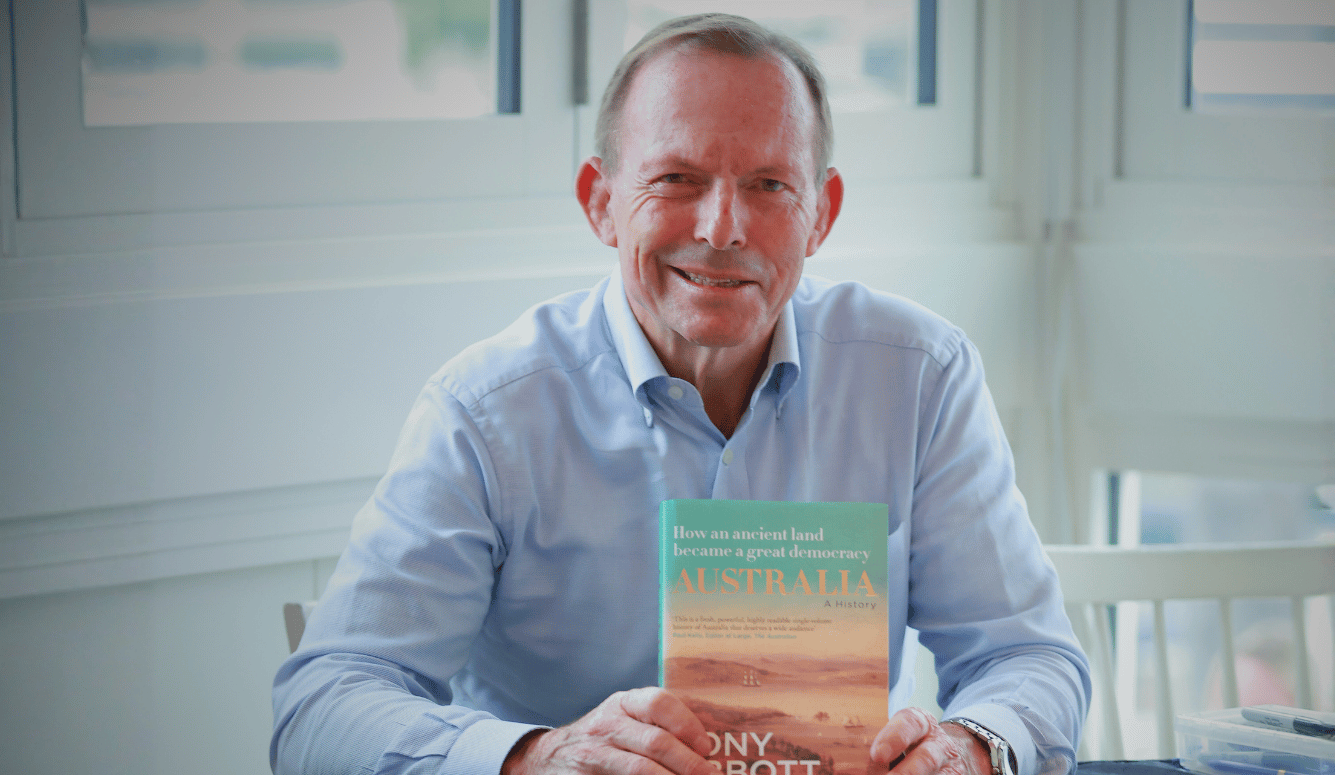

Tony Abbott argues that Australia’s history provides a lot to be proud of.

A Review of Australia: A History by Tony Abbott, 448 pages, Harper Collins AU (February 2026).

It is not often a former Prime Minister writes a history of his country. Winston Churchill wrote numerous books on British and Imperial history, some sprawling over multiple volumes. By contrast, Tony Abbott’s single volume, Australia: A History, is short. Its brevity is facilitated by the brevity of Australia’s history (construed as what is written down) as distinct from its prehistory (which is passed on through oral traditions or is inferred from archaeological digs and the like). This is not a criticism.

The written history of Australia prior to 1788 is sparse. There were a few dozen documented landings on the north, west, and south coasts, all of which recorded much the same thing: The natives are naked and hostile; or they are naked and evasive. There is no sign of gold, silver, nutmeg or any other spice of value. Zero investment potential here. Move on. Among the most widely quoted assessment is that of the English pirate turned Royal Navy officer, William Dampier, who described the Australian Aborigines as “the miserabilist people in the world,” owing to their nudity and lack of material possessions.

Tony Abbott was prime minister of Australia from 2013–15. He also came close to winning the 2010 election, which resulted in a hung parliament, but Labor rival Julia Gillard was able to cobble together a majority by negotiating with three independents and a Green. When he did come to power at the next election, his background as a Catholic seminarian who competed in surf races wearing budgie smugglers was widely derided, as were the two Oxford Blues he won as a boxer. Nicknamed “the Mad Monk”—his name was frequently misspelled as Abbot—he was a cartoonist’s dream and his Catholic observances were far more heavily scrutinised in the 2013 election than the Anglican ones of his opponent, Kevin Rudd.

Abbott went to Oxford on a Rhodes Scholarship, a prestigious award, not generally handed out to dunces. While often characterised as a pugilistic thug and attack dog in politics, his writing is lucid, clear, and well argued. He makes the point that while Australian history has some dark episodes, for the most part it is a history Australians can be proud of, whatever their race and wherever they come from. To be Australian, he says, is to win the lottery of life.

He states his agenda early on, in an Author’s Note:

This is the book that should never have been needed. Until quite recently it was taken for granted that Australia was a country that all its citizens could take pride in, even the Aboriginal people, for whom the 1967 referendum marked full, if belated, acceptance into the Australian community. But a generation of anxiety over Indigenous dispossession, and the academic triumph of what Geoffrey Blainey has called the “black armband view” of Australian history, has left many Australians ambivalent about our past, even though it is far more good than bad.

Abbott rejects the “Invasion Day” narrative that sees dispossession of the indigenous population as a massive failure for which contemporary Australia must atone through the agenda of “Voice, Truth, and Treaty” proposed in the Uluru Statement from the Heart. Tellingly, he ends his history with the rejection of the Voice in the 2023 referendum. He says Australia did right to reject an exclusive “indigenous only” race-based addition to our constitution.

Abbott does not omit key facts about Aboriginal dispossession. He simply makes the argument that is should be a source of pride and wonder that a society established as a penal settlement turned out to be one of the most successful and stable liberal democracies in the world.