Australia

The Gentle Wildness of Tasmania

Tasmania has all the majesty of other windswept high-latitude places, but it has always been less barren, more hospitable, more generous in its beauty.

The love of field and coppice,

Of green and shaded lanes.

Of ordered woods and gardens

Is running in your veins,

Strong love of grey-blue distance

Brown streams and soft, dim skies

I know but cannot share it,

My love is otherwise.

These are the opening lines of Dorothea Mackellar’s 1908 poem, “My Country,” a poem well known to almost everyone who has grown up in Australia (though I had never heard it before coming here). Despite the familiarity that allowed her to recite much of it from memory, barely glancing at the page, my best friend’s eyes gleamed a little with welling tears, as she read it to me for the first time. The poem—which is indeed beautiful and moving—relates the difference between the ordered, parcelled, tamed bucolic beauty of the English countryside with its hedgerows and roses and its cloudy skies on the one hand and the wild, rugged, parched, “sunburned” “wide brown land” of Australia with its “pitiless blue sky” and “hot gold hush at noon” on the other. But what Mackellar is describing is the large island shaped like a bulldog’s head in profile that people in Tasmania call “the mainland.” Tasmania is very different. “We read that poem in school,” a local friend told me. “I couldn’t really relate to it.”

In his book, Van Diemen’s Land: A History, James Boyce argues that the first Europeans to reach Tasmania encountered a place whose contours seemed reassuringly familiar. They remarked approvingly on the salubrious climate, which reminded them of the weather back home—though brighter, clearer, and sunnier, at least on the island’s more sheltered east coast. Hobart enjoys 40–60 percent more hours of sunshine per year on average than London—when I asked Google AI to compile those figures, it volunteered unprompted, “Think of Tasmania as a greener, wilder version of the UK … You’ll find similar temperate charm but with more sunshine and less of the UK’s infamous dreary greyness.” The early British settlers felt much the same way, if Boyce’s version of events is to be believed.

The Aboriginal practice of using fire to clear areas of forest in order to flush out kangaroo and wallaby, coupled with those herbivores’ assiduous munchings, created in Tasmania a landscape of forests interspersed with pastures, reminiscent of the landscaped estates of the old country, with their woodlands and sweeping lawns. Hobart has the same Köppen classification as London: temperate, oceanic—with warm weather in summer and rain all year round (though the rain in Hobart tends to fall as light showers of ten to fifteen minutes of drizzle at a time, just enough to make you pull the hood of your cagoule up, not enough to take out an umbrella). Eastern Tasmania enjoys relatively mild weather, then, and—unlike much of the Australian mainland—has plenty of readily available clean, fresh water, even in the densest bushland.

Tasmania’s earliest inhabitants, a tiny population stranded on the island after sea levels rose, lost much of the technology that mainland Aborigines relied upon. Yet despite the flimsiness of their stringybark canoes, the crude design of their waddy clubs and digging sticks, and their nakedness through the blustery southern winters—with only animal grease and wallaby fleeces slung over their shoulders to keep out the wind—the island sustained them. They hunted its marsupials and hauled its mutton birds out of their tunnel nests; they clubbed its seals and dove into the bone-chilling waters for its oysters and its abalone. The weather can be bracing, but the place has never been a frozen wasteland, not within human memory.

Then in the early nineteenth century, the Brits set up shop. The second shipload, a motley crew of convicts, soldiers, and settlers, under the spiritual guidance of the Reverend Bobby Knopwood, an irascible alcoholic who had squandered his family fortune at the gaming tables—sailed into Sullivans Cove in 1804. They quickly found that the place had an important additional advantage over the mainland: there have never been native dingoes on the island. Thus, the wildlife was unused to canids and the dogs the newcomers brought with them proved very effective at hunting macropods. Knopwood’s beloved Spot was the nemesis of 141 Forester kangaroos in a single year.

“Nowhere else in the New World,” Boyce writes, “did Britons adapt so quickly or so comprehensively to the … new environment.” It was easier to live off the land there, thus “many convicts simply wandered off to live a life of quiet freedom in the well-watered, game-rich bush.” This was, he claims, to shape Tasmanian history, as it allowed the convicts a greater degree of independence than elsewhere in the Australian colonies. It was cheap and efficient to let them grow their own food on small farmsteads and hunt their own meat. This was the origin of the Tasmanian system of “thirds,” in which convicts were allowed a share in the animals born to the flocks they grazed in the bush on behalf of the stock owners. And the relatively hospitable local geography also provided the ideal environment for resourceful outlaws: Tasmania has forests dense enough to hide in, but a landscape fruitful enough to feed and water you.

This expansion outwards across the island was rapid and it brought tragedy in its wake. As the newcomers laid claim to an ever-expanding sweep of country, grazing their merinos on the rich grasslands, decimating the populations of kangaroo and emu, appropriating the Aboriginal hunting grounds for their homesteads and farms, they clashed ever more violently with the original inhabitants until finally the latter had been completely displaced. The last fully indigenous Tasmanian, a woman called Truganini, died in 1876, exiled and alone. As I was to quickly learn, it’s a feature of Tasmania that the greatest man-made horrors took place amid the most breathtaking natural beauty.

Just like those first Europeans to reach the island—at least, according to Boyce’s telling—I too had an immediate sense of familiarity. As I stepped out of Hobart airport and felt the chilly breeze and saw the blue contours of mountains in the background, I felt that I had circled half the globe and, more than ten thousand miles from where my life began, found myself in Scotland again. It was a feeling that was to return multiple times, whenever I was surveying the topography of the place from afar. From a distance, the silhouettes of Tasmania’s mountains, the shapes of lakes, rivers, estuaries and inlets, looked Nordic to my European eyes. But from close to, the place was far more densely forested, richer and more diverse in its plant life, teeming with animals—far less barren.

In her novel, The Left Hand of Darkness, Ursula le Guin describes the ecology of the planet Gethen (“Winter”) that is just emerging from an ice age. Vast herds of “yonder-beast”—the only animal in sight—migrate across the frozen planes and the wooded areas are largely monocultures. The narrator explains:

Though the number of native species, plant or animal, on Winter is unusually small, the membership of each species is very large: there were thousands of square miles of thore-trees, and nothing much else, in that forest.

All the cold, windy, hilly places I’ve ever known have been like Gethen: barren, with few species—in Scotland, these are rabbits and deer—though perhaps many individuals, and with vast areas containing only a few kinds of fir or pine, broken up by the occasional stand of silver birch or straggly rowan, its crimson berries a welcome respite from the muted greys and browns. Scotland, Sweden, Norway, Iceland, Canada: these countries all have their beauties but I couldn’t help seeing Tasmania as Scotland upgraded. Its humpbacked ridgelines and scalloped bays, its jagged, snow-dusted mountaintops and gleaming kidney-shaped lakes have all the grandeur of those northern lands, but close-to, they have a less austere quality. Echidnas nose around the forest floors; the eyes of spotted-tailed quolls flash out at your torch beam in the darkness of a farm; bright-eyed black hens zip along grassy paths—the lovingly-named turbo chooks, who can run at up to 40 km an hour; the dark glossy water of the Hobart rivulet is alive with platypus.

Even up on Cradle Mountain, where I tramped along raised wooden walkways over boggy marshlands, my head bent against a rain that seemed to defy physics and come at me from all directions at once, the wild, forsaken quality of the moorland was tempered by the loveliness of the local fauna. The place was less a frozen Narnia than a magical Hundred Acre Wood. Everywhere I looked, the slopes were strewn with round balls of brown fur. From closer to, I could see them bumbling along, eyes down, nosing the ground, poking heads out of burrows like friendly hobbits. One of them clambered up onto the walkway, stopping to twerk its bottom back and forth against a post, then padded towards us, pigeontoed, with a quiet tappety-tap of its onyx-coloured claws against the damp wood and awkwardly climbed some stairs, bottom wiggling like a marsupial Beyoncé. This is Tasmania: majestic landscapes from afar; adorable animals from close to. I think it’s spoiled me for the high latitude wildernesses of the northern hemisphere. Of course, it lacks the historic cities and castles of the older northern countries—there’s no Stirling, no Glamis, no Royal Mile—but otherwise, as I told everyone I met, it’s like Scotland—but better, more opulent in its beauty, more generous in its wildlife, more loveable.

This is part of why, although I’ll write Tasmania here in full, I rarely say the whole name. I haven’t got accustomed to the Australian habit of abbreviating everything: brekkie, truckie, barbie, firie, Macca’s, doco, servo, bottle-o etc. But in this case, I can’t stop calling it Tassie. It’s like my impulse to call my close friends darling. Every mention is an opportunity to express my affection and, like a lover, I can’t stop advertising my feelings, laying claim to an intimacy with the place. As soon as I open my mouth, my voice proclaims how foreign I am to Australia, but like most converts, I’m zealous. It’s Tassie to me.

There really is beauty in abundance here and in a concentration I’ve experienced in few other places. (Sri Lanka is one of those places—it seems fair to think of Tasmania as Australia’s Sri Lanka in reverse, an island dangling from the edge of a larger country, containing many of that country’s landscapes in miniature, compacted into a smaller space.)

Courtesy of a friend, I was staying at a house a ten-minute drive from Hobart. The approach is up a steep driveway off a quiet winding road that already feels rural, despite its proximity to the island’s largest city. As my Uber drove up, a wallaby perched on its hind feet for a moment, observing us—a plump joey peeking out of her bulging pouch—and then bounded away. The grass at the side of the driveway was alive with tiny black rabbits (surely the most adorable of pests). The back of the house is lined by French windows that slide open onto a deck whose swing chair overlooks a breathtaking scene: the tufted grass-strewn fields give way to wooded hills and nestled in their cleavage a fat line of blue marks the Derwent River. I woke up every day to wallabies grazing in the tiny patch of garden right below my bedroom window, thumpeting-thumping away as soon as they heard me drawing the curtains. They returned towards sunset every day: I could usually spot a dozen or more at a time cropping the grass in the golden light of evening.

There seems to be a kind of gradient of Britishness in Australia. Up in Central Queensland—the furthest north I’ve been so far—convergent evolution has created a culture of wide roads and cowboys, with utes and Akubras standing in for pick-up trucks and Stetsons. Every man, to a first approximation, is Bob Katter, who may be Lebanese by descent but is as spiritually Australian as it’s possible to be. Days are hot, vowels are long and lazy, the red expanse of the desert is on the doorstep and men are lounging around in wifebeaters drinking stubbies. By contrast, Hobart is the most English place I’ve seen outside the motherland. Roses nod in the wind in every front garden. I’ve never seen so many roses in a single town (outside of dedicated botanical gardens): chalky white blooms are particularly abundant, but there is also a multitude of scarlet, crimson, hot pink, magenta, and daffodil yellow flowers. It feels more like Aldeburgh in Suffolk than anywhere I’ve visited in Australia so far. Beaches are not for surfing, but for breezy walks with your golden Lab, after which you can warm up at the pub—a “hotel” as Aussies charmingly call it, using a word that recalls their origins as staging places where you could change your horses on a long coach journey. My local companion drinks tea every hour on the hour. It’s English-er than England: a quaint and lovely version of the old country.

There are vistas in Hobart from almost every direction, even as you approach the place, over an exhilaratingly high bridge across the wide estuary. On three sides are ridges of hills and on the fourth, the view out towards the open ocean. And so many of the streets lead upwards, offering view after view of hills and water. It’s chilly in the shade but warm in the bright sunshine whenever the wind dies down. I never tire of a sea view—it’s one of the things that are immune to hedonic depletion. My eyes never weary of those shades of turquoise and azure. And, as with every seaside place, there is always a sense of the possibility of travel and adventure. A coastal town is a point of departure and that feels especially tangible here, at the ends of the Earth. Southwards, there is nothing between here and Antarctica; and if you sail westwards, along the roaring forties, you won’t make landfall again until you reach the pampas grasslands of Argentina. I love the nautical feel of the place: the long wooden quaysides, the former warehouses and jam factories, the lookouts on Battery Point, where the old city defences were stationed—defences never needed as no one came all the way out here; no shot was fired in anger—the plump Bruny Island oysters and the creamy scallops; the CSIRO icebreaker ship at anchor, resting between Antarctic missions; the yachts listing in the wind off Sandy Bay.

And Hobart is just the beginning of the beauties, as I’m soon to realise. Of everywhere I’ve visited in the world, only Venice has more photogenic vistas. This was true even in Port Arthur, the scene of brutal punishment, where convicts were kept in cells no bigger than a Portaloo and the worst offenders were housed in a diabolical silent prison, a kind of devil’s convent in which they were not allowed to speak or even catch glimpses of each other. The only place where they could use their voices was singing hymns in chapel, and even there, each man was walled from the others by claustrophobic wooden dividing panels, man-high blinkers. Yet the soft rolling hills, the lovely scoop of bay, the oaks and bluegums and cypresses—all make for a place that is paradoxically elysian. The contrast was even starker on Sarah Island, once a barren, wind-lashed, frozen rock where convicts laboured year-round waist-deep in the Tassie ocean—breath-catchingly chilly on even the warmest day— stumbling along in their rusting ankle chains. The lush local vegetation has reconquered the island now and when I visited, on an unusually hot, still afternoon, it seemed like a tropical paradise.

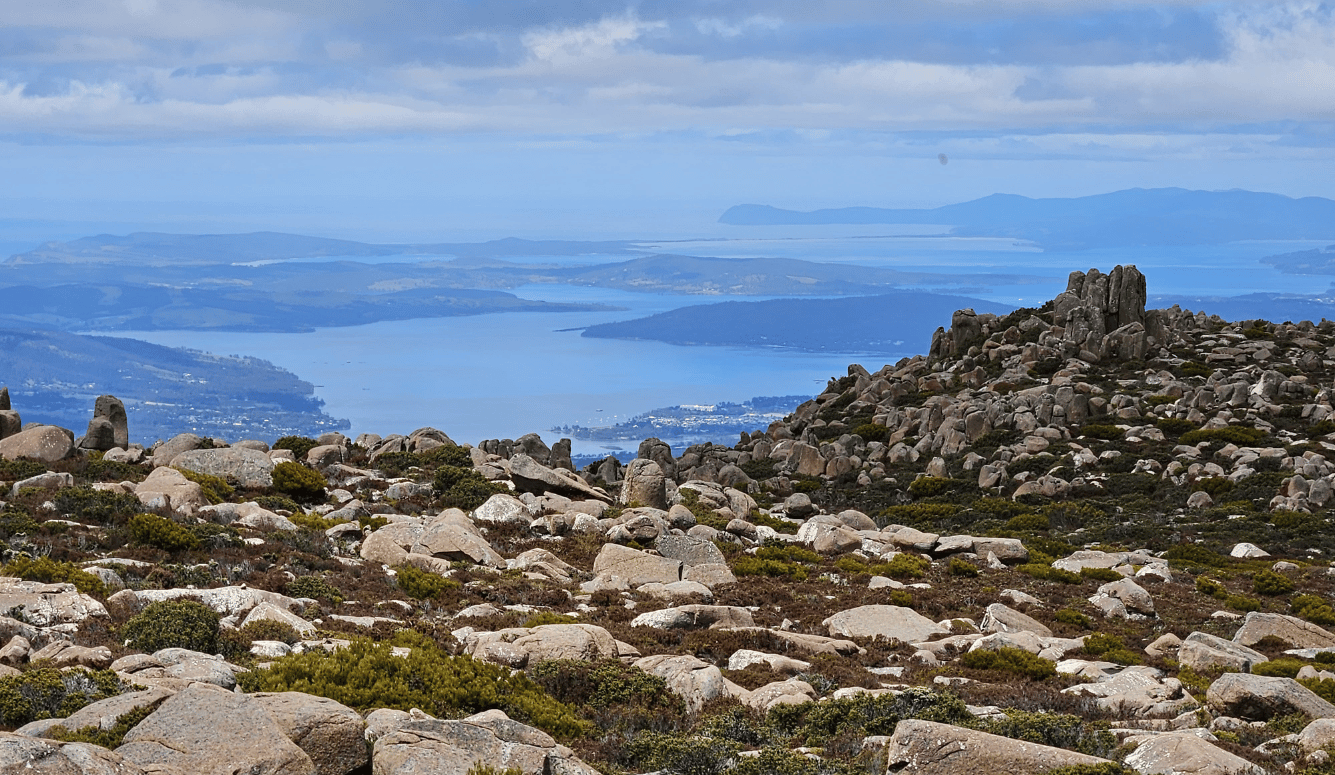

When Anthony Trollope visited Hobart in 1872, he remarked of Mount Wellington, the hunchbacked mass that looms over the city, that it is “just enough of a mountain to give excitement to ladies and gentlemen in middle life.” As a lady in middle life myself, I concur: Mount Wellington is no mere hill; it’s high enough to have its own weather system. The upper plateau can be dusted with snow at any time of the year, including summer; thick layers of slate-grey cumulonimbus clouds threaten to block out the sight of the spectacular panorama below at any moment. (“We have a saying in Tassie,” a friend told me. “The view should not be mist.”) A high plain stretches out to the horizon, strewn with lichen-freckled boulders, an obstacle course of swamp and ice-cold pools with spiky scoparia growing out of every crevice. The ground is strewn with the cuboid scats of wombats.

Tasmania is wildest on its lonely west coast, of course, seven thousand miles from its nearest neighbour. And it’s at its most impoverished here, too. I knew that Tasmania was the poorest of the Australian states (as measured in terms of average income) but amid the relative gentility of Hobart, I had little sense of that. On the west coast, it is far more palpable. Many of the houses are built of fibrous cement sheet (fibro), a material cheaper but flimsier than brickwork and whose porosity makes those homes either freezing or prohibitively expensive to heat, in a place where you’re likely to need to operate your heat pump almost every day. Clapboard slats are made of aluminium or plastic, rather than wood. Front gardens sport rusted prams. There’s a level of quiet squalor that I haven’t seen elsewhere in Australia. Many of the smaller towns bear the relics of a more prosperous age, constructed during the boom times of the mining industry: grand art deco cinemas and theatres—now boarded up—magnificent post offices recalling a time when postal deliveries brought news and excitement; fragments of train tracks, stranded amid the tarmac of car parks. Tiger snakes—which despite their name are jet black in Tassie, all the better to absorb the sparse heat—are coiled amid the scrubby grass verges. Everywhere, the local rhododendrons are in luxuriant bloom: the poorer-looking their surroundings, the more opulent their displays of shocking pink flowers.

This is Tassie in a nutshell: wildness is tempered by loveliness everywhere you look: from the stylish olive grey and ashy blue of the Tassie rosellas to the drunken waddle of the fairy penguins as they stumble up the dunes in the moonlight. I am a hot weather girl, a lover of the heavy caress of tropical air, of lush jungle and long warm evenings. But even I must admit: it’s the most beautiful place I’ve ever been.