Politics

Sudan Between Two Middle Easts

Between the jihad of the “Hamas of Africa” and the new order of the Abraham Accords, the choice in Sudan should be clear.

The war in Sudan is not just another failed revolution, it is the fault line between two Middle Easts. On one side stands the rejectionist order consecrated in the “Three Nos” of the 1967 Khartoum Conference, flatly refusing peace with Israel, recognition of Israel, and negotiations with Israel. On the other side stands the imperfect experiment of the Abraham Accords, where Arab states normalise Jewish sovereignty, pluralism, and the unromantic work of state-building instead of worshipping “resistance.” This is why Sudan’s civil war cannot be reduced to a quarrel between “competing generals.” It is a struggle over whether the post-Islamist civic opening that briefly existed in 2019 will be buried for good or whether Sudan will be allowed to create a moderate order, divorced from the Muslim Brotherhood and at peace with Jews and its own persecuted communities.

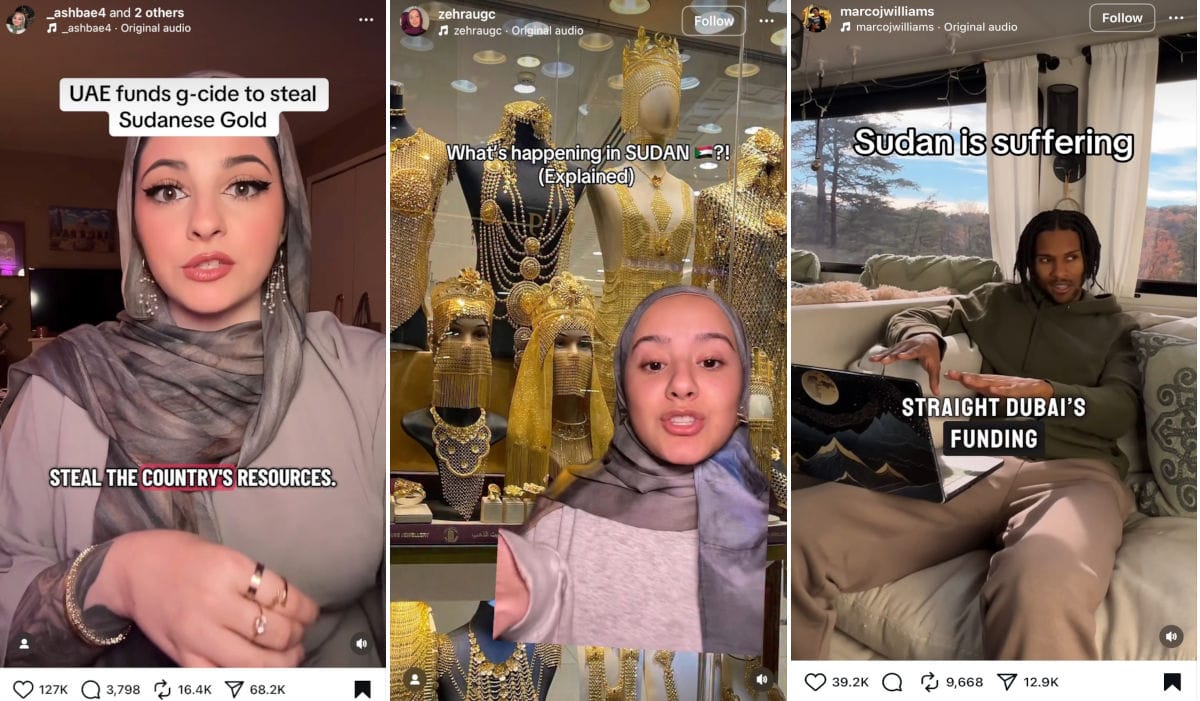

The most efficient weapon in this struggle is narrative. A Qatar-aligned media ecosystem has repackaged Sudan for Western consumption as a morality play in which the United Arab Emirates is cast as a genocidal neocolonialist state—a “new Israel” for the same “progressive” audience—while the Islamist infrastructure embedded in Sudan’s security apparatus slips out of frame. The strategic reality, however, looks very different. Iran has restored relations with Khartoum, and Reuters reports that Iranian drones are assisting the Sudanese army’s campaign around the capital.

This is how Islamists return: by fogging the West while they wage war in the East. The campaign against Abu Dhabi, cast as the master culprit in Qatar’s version of events, does not illuminate Sudan’s catastrophe, it obscures it, laundering the forces that strangled the transition, erasing Sudan’s own Arab Islamist colonial hierarchy, and hardening the region’s addiction to permanent war just as denazification and regional integration begin to look possible.

I. Massacre, Marriage, and the Brief Birth of a Civic Sudan

In late June 2019, I landed at Heathrow and was met by my then-husband, a British Sudanese oil-and-gas lawyer who had reinvented himself as a revolutionary. “There is something I must tell you,” he had said earlier that week, “but I cannot share it over the phone.” He had just filed a petition with the International Criminal Court calling for an investigation into the Khartoum massacre. On 3 June 2019, in the pre-dawn hours of Eid al Fitr, the holiday celebrating the end of Ramadan, Sudanese security forces stormed a peaceful sit-in. A couple of hundred people were killed, women were raped, and bodies were dumped in the Nile. The sit-in had been the beating heart of a new, hopeful Sudan. It was met with bloodshed.

The petition went viral and journalists began calling our Shoreditch hotel room. My ex-husband was intoxicated by the idea that he might have a role in the revolution. Like many “progressives” in 2019, he had flown into Khartoum for a weekend, taken selfies at the protest site, and returned home a self-anointed leader of the people. He sat me on the edge of the bed. “There is a transitional plan,” he said. “My name is on a list presented by the Sudanese Professionals Association as a possible technocratic head of state, at least for an interim period. Are you in?” I asked him if he was insane. “They will murder you,” I replied, “and they will rape me before they kill me.” The Sudanese deep state was not about to abandon its theocratic project because a few lawyers drafted a road map and some Ivy-educated men imagined themselves to be the midwives of a new democracy.

That night marked the beginning of the end of our marriage. We divorced the same week the Abraham Accords were announced in 2020. By then, what I had learned about Sudan’s Islamists, and about the regional forces trying to drag us back to the seventh century, had sharpened my view of every other conflict in the Middle East.

To understand what is being destroyed in Sudan today, it is important to know what briefly came into being. After three decades of Omar al-Bashir’s rule—a blend of military dictatorship and Muslim Brotherhood ideology—Sudan erupted in December 2018. Bread prices were the trigger, but the deeper cause was the cost of a racial-theological system that starved and bombed the country’s peripheries while enriching an Arabised elite along the Nile. Women, hailed as Kandakas in reference to Nubian warrior queens, became icons of the uprising. The chant Hurriya, Salam, wa ʿAdala (“freedom, peace, and justice”) rang out as a civic demand rather than an Islamist slogan or an Arab nationalist call. For the first time, the dominant call was not “Islam is the solution!” but “Down with the Kizan!” (the local term for Sudan’s branch of the Muslim Brotherhood).

The transitional government that followed was led by prime minister Abdalla Hamdok, and it included four women as well as technocrats like former justice minister Nasredeen Abdulbari. This was the most inclusive administration in Sudan’s modern history. Representatives from regions previously treated as disposable—Darfur, Kordofan, the Nuba Mountains, and Blue Nile—held key portfolios. Abdulbari, who hails from Darfur, set out to dismantle the legal infrastructure of Sudan’s Islamised apartheid. The Public Order laws that policed women’s bodies and behaviour were repealed. Statutes criminalising apostasy and alcohol consumption were reformed. Early steps were taken to roll back the architecture of second-class citizenship for non-Muslims and non-Arabs. This was not Western liberalism transplanted to Khartoum, but it was an attempt to place citizenship, not creed or ethnicity, at the centre of the state.

The most radical move occurred when Sudan signalled its intention to join the Abraham Accords and normalise relations with Israel. In exchange, it would be removed from the United States’ list of state sponsors of terrorism. I interviewed the young minister of justice who led Sudan’s delegation in the preliminary talks, who told me that he spent hours arguing with sceptical youth activists in his office. Sudan’s past, he maintained, had to be disowned. A different future required new alliances and a new attitude to Jewish sovereignty.

Sudan signed the Abraham Accords declaration on 6 January 2021. But in October 2021, about four weeks before the minister of justice was due to fly to Washington to formalise the trilateral agreement with the United States and Israel, the old order snapped back. General Abdel Fattah al Burhan led a military coup that dissolved the civilian cabinet and arrested ministers. The experiment in post-Islamist pluralism was put on life support.

II. Sudan’s Original Sin and the New Islamist War

The 2021 coup did not simply return Sudan to military rule, it re-inscribed the state’s original sin. Since independence in 1956, power has been concentrated in an Arabised Nile Valley elite that built a state in its own image, consigning the rest of the country to dispossession and death. What postcolonial theorists call “whiteness” in the West has an analogue in the East. In Sudan, Arabness has functioned as an imperial identity rather than a neutral ethnicity, weaponised against black, non-Arab, and non-Muslim populations in the South, the Nuba Mountains, Darfur, and Blue Nile.

By the early 1990s, this hierarchy had been sacralised into a genocidal theology. Under the tutelage of the Sudanese Muslim Brotherhood leader Hassan al Turabi, whose Islamist project hosted Osama bin Laden and turned Khartoum into a hub for global jihad, religious authorities moved from prejudice to extermination. At a 1992 conference in El Obeid, clerics issued a fatwa declaring jihad against “infidels, hypocrites, and rebels” in the Nuba Mountains, with the stated goal of Islamising them or purging them from society. Genocide was not an accident of war, it was mandated as religious duty.

The cultural groundwork for this was laid decades earlier by Hitler’s favourite filmmaker. In the 1960s and 1970s, Leni Riefenstahl, director of Triumph of the Will and Olympia, rebranded herself as an ethnographic photographer and turned the Nuba into coffee-table ornaments. Her books The Last of the Nuba and The People of Kau depicted Nuba men and women as perfectly sculpted, often naked athletes, frozen in ancient wrestling and body-painting rituals, as if they were already part of the past. Orientalist photographers had done the same to Jews from North Africa before those communities were ethnically cleansed.

A brutally linear sequence followed in Sudan. Omar al-Bashir’s Arab Islamist regime reclassified the Nuba as internal enemies, “kuffar” to be converted or purged. Villages were bombed, families were driven into caves, and communities were starved under siege. Eyes and Ears of God, a 2012 documentary stitched together from smuggled camera footage, records what happened to Riefenstahl’s “last of the Nuba” once the photographers left and documents the aerial bombardment and ground attacks that followed. When I describe Sudan’s post-2019 transitional chapter as an attempted “denazification,” I mean it literally: the dismantling of a pan-Arab & pan-Islamist supremacist state that fused fascist aesthetics, genocidal doctrine, and a hierarchy lifted straight out of mid-20th-century Europe.

Against that harrowing background, Sudan’s decision to sign the Abraham Accords declaration in 2021 was a 180-degree turn. A state that once anchored Arab Nazism now gestured toward an order that accepted Jewish sovereignty, renounced holy war as statecraft, and imagined peace as an end state rather than a mere condition for diplomacy. The 2021 coup was the Islamist response. On 15 April 2023, a simmering struggle between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) under Abdel Fattah al-Burhan and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) under Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (Hemedti) exploded into open war in Khartoum. During our interview, Nasredeen Abdulbari, now a fellow at the Atlantic Council, stressed that this was not simply a power struggle. Burhan had offered to share power with Hemedti, but once the RSF aligned itself with pro-democracy organisations, the confrontation became existential for the old order. The war spread to Darfur, Kordofan, and beyond.

As the conflict enters its third year, estimates suggest that hundreds of thousands have perished, many from hunger and preventable disease rather than direct violence. Nearly twelve million people have been displaced—the largest displacement crisis in the world. Port Sudan, on the Red Sea coast, has become a congested substitute capital, while Khartoum and the second-largest city of Omdurman lie in ruins.

Sudan controls roughly 750 kilometres of Red Sea coastline, including ports that handle most of the country’s external trade. This shoreline anchors a corridor that carries a significant share of global maritime commerce, one already disrupted by Houthi attacks that have diverted traffic away from the Red Sea and slashed Egypt’s Suez Canal income. On land, Sudan borders seven fragile or strategic states: Egypt, Libya, Chad, South Sudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea, and the Central African Republic, placing it at the heart of the Arab African belt.

Historically, Sudan has also served as a passageway for Iranian weapons headed to Hamas. Israeli strikes on convoys in Sudan in 2009 and later reports about the Yarmouk munitions factory briefly brought that network into the open. More recently, Sudan has been implicated in suspected smuggling routes that could benefit Iran’s Houthi allies along the Red Sea. The country’s brief civic interlude was the first serious test of whether a post-Islamist, Abraham Accords-style order could replace a legacy of Arab Islamist colonialism. If Sudan tips decisively into the orbit of the Axis of Resistance, not only will the country’s humanitarian catastrophe worsen, but it will also become a major depot for Iranian arms and a launching pad for endless Islamist wars along the Red Sea. This threatens the heart of Africa as well as Israel and the moderating Gulf states.

In Washington and Brussels, the temptation is to assign familiar roles to the belligerents: the SAF as “the state” and the RSF as “the militia.” Inside Sudan, the story is more complicated. In Khartoum and the Arabised north, many middle-class Sudanese still insist that only the SAF can ultimately serve the people. Their reasoning ranges from ideological or historical loyalties to pragmatic institutional considerations. The army has barracks, payrolls, embassies, and a flag. A Sudanese lawyer friend in the Gulf told me, “We can always get rid of Burhan. The army is the only institution that can protect everyone, and it will still be there.” It is easier to imagine reforming a familiar army than living under a militia, particularly one drawn from the same communities the state has long portrayed as uncivilised savages. For Arab-passing Muslim elites, the SAF has also been the shield that protects their privileges. The state may have been brutal, but it was theirs, even if the more secular among them cheered when Bashir fell.

In Darfur, the Nuba Mountains, Blue Nile, and other shattered peripheries, the story is reversed. There, the Sudanese state has been experienced less as an institution than as a machine of mass murder and religious cleansing. Entire villages were wiped out under the national flag and in the name of Islam as defined by the theocratic supremacists in Khartoum. The displaced were pushed into city slums, used as cheap labour, and treated as permanent suspects rather than citizens. For many of these communities, the RSF now looks less like a death squad and more like a liberation army, or at least a vehicle for a Sudan in which they are no longer expendable.

Sudanese journalist Abdelmoneim Suleiman, founder of Sudan Peace Tracker, told me he created his English-language platform because Islamists from the old regime were monopolising the story of the war through the army and institutional media they still dominate. On the ground, he says, loyalties are more nuanced. In Darfur, some former officials of the old order now work against the RSF. In the SAF-controlled capital, small networks of activists have quietly edged towards the RSF. Beneath those shifting alliances runs a simpler fault line between architects of the old Islamist order and those who broke with it in 2019 and are now being punished. Suleiman explained that Hemedti is even held responsible for enabling the military coup against the old regime.

The RSF’s image is stained by its association with the Janjaweed, the militia Omar al-Bashir created as a deniable killing force to ethnically cleanse Darfur in the early 2000s. The RSF was formally established in 2013 under Hemedti and absorbed many Janjaweed fighters, but it also recruited heavily from borderland communities and groups the central state had long excluded. During our interview, Nasredeen Abdulbari explained that many of today’s RSF fighters who are now in their twenties and thirties, were children, or not yet born, during the height of the Darfur genocide and therefore could not have participated in those original crimes. During his ministerial tenure, Abdulbari learned from both SAF and RSF officers that vetting processes had excluded roughly 14,000 of about 24,000 former Janjaweed members with documented abuses, although those numbers cannot be independently verified.

Musa Hilal was the Janjaweed’s most infamous commander, and his career stretches from the regime’s original killing machine in Darfur to the militias he still influences today. Hilal was among the first Sudanese figures sanctioned by the United States for atrocities in Darfur. Since 2024, he has publicly declared his alignment with the Sudanese Armed Forces and “state institutions,” and urged his Mahamid followers to back the army against the RSF. The SAF is not building a single, professional national army; it is reverting to its old habit of manufacturing and reactivating sub-militias, including Hilal’s men. According to a Darfuri activist I spoke to, fighters mobilised through SAF channels—including some dressed in RSF uniforms in a pattern flagged by RSF official Mohamed Mukhtar—have participated in recent massacres that outside observers nonetheless attribute to Hemedti.

Regardless of how the RSF is perceived abroad, many in Darfur and Kordofan see it as the only force that has ever seriously challenged the Khartoum-centric Arab Islamist state. And for now, it is winning on the ground. After encircling El Fasher for roughly a year, the RSF now controls all five Darfuri state capitals and large parts of western and central Sudan. Recent reporting suggests it holds roughly a third to a half of the country’s territory. Human-rights advocate Guy Josif, now at the Wilson Center and himself a survivor of ethnic cleansing, told me that, despite his own fears, the RSF is the only armed actor that has ever defended his community against genocide. For many in the periphery, the RSF is what counts as protection when the state has been the predator.

The man so many in Khartoum insist can be “forced out later” sits at the centre of this map. Before becoming de facto head of state, Burhan served as regional commander and inspector general of the army in Darfur. In that capacity, he oversaw operations in the region now reduced to rubble and managed the flow of gold and other resources that enriched Sudanese officers and their regional partners. For years, he guaranteed a steady stream of Sudanese goods, from cattle to agricultural exports, which helped secure Saudi backing, according to a Washington DC-based Sudanese dissident I spoke to. Since the 2021 coup, that stream has expanded to include weapons and drones from Iran. The result is that Burhan now operates as Iran’s man in Sudan, presiding over a regime that has turned the country into a terror gateway for Tehran, Hezbollah, and the wider axis aligned against Israel and its Arab partners.

On 9 October 2023, shortly after Iran and the Muslim Brotherhood declared a multi-front war on Israel, Sudan and Iran formally restored diplomatic relations. Since then, reports have described deepening military cooperation, including shipments of Iranian weapons and drones that helped the SAF regain ground around Khartoum and Omdurman, and the integration of openly jihadist formations—like the brutal Turkish-backed al-Bara Ibn Malik brigade—into the war effort. The Sudan–Libya–Egypt tri-border has become a smuggling corridor, allowing Iran to move weapons and fighters toward Israel’s borders and the Red Sea chokepoints. Israeli analysts warn that drones launched from Sudan could threaten Eilat and Israeli shipping routes, and that Sudan’s army is mutating into the “Hamas of Africa.” Burhan’s permanence would mean an Iranian outpost on Israel’s southern flank.

This is not only external capture, it is internal continuity. The old regime spent decades Islamising the officer corps and security services. Suleiman says the figures he discussed with Burhan during the transition suggested that most senior officers, nearly all intelligence chiefs, and many top police officials came from Muslim Brotherhood networks or their offshoots. Burhan, he adds, is a “habitual liar” who performs moderation for visitors while advancing the Brotherhood’s agenda. The army is being hollowed out from within, increasingly resembling a Sudanese Hezbollah model, a “national” shell for transnational jihadists and their patrons, some of whom are already boasting that they will “free al-Aqsa” after Sudan.

SAF outreach to Iran rests on shared convictions: hostility to liberal democracy and to the indigenous peoples of the region, including Jews in Israel. Sudan remains multi-ethnic and multi-religious, with large non-Arab communities and a Christian and indigenous-faith minority. The slogan South Sudanese protesters carried—“We are not the worst Arabs, we are the best Africans”—was a verdict on Arab Islamist domination, and a warning that without pluralism the country will keep choosing rebellion over submission.

Suleiman hopes the world will see that the Sudanese deserve more than to be used as disposable pawns in someone else’s holy war. Rescuing them from the jaws of the Islamist beast is a moral duty and a strategic necessity. “The men now fighting in Sudan in Palestinian keffiyehs, vowing that their next battle will be against Israel, are telling us plainly that the monster will not stop at Sudan’s borders if it is allowed to win,” he says.

III. Making the UAE the New Israel

If the military struggle in Sudan is a contest between two Middle Easts, the media war is a contest over which one Western audiences will see. Al Jazeera, the flagship broadcaster of a Muslim Brotherhood-adjacent worldview, treats every counter-Islamist project as “colonial” and every Islamist client as “resistance.”

Watch a handful of AJ+ videos on Sudan and El Fasher and you will recognise a familiar script from Gaza. In Sudan, El Fasher is “under siege” and “starved”; the RSF is the sole genocidal aggressor; and the SAF and its Islamist allies are reframed as the last line of defence against colonialism for an already embattled black population. The RSF is accused of desecrating mosques, a charge routinely levelled at the IDF. Hovering over it all is a single, obsessive external villain: the United Arab Emirates, alleged to be arming the RSF to stage a colonial plunder of Sudanese gold. Iranian outlets have even tried to link the UAE to the Epstein files, a smear lifted straight from the antisemitic imagination.

In a story reminiscent of Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves, Al Jazeera has cast the UAE in the role of the greedy older brother. In this narrative, the UAE becomes a new Israel in a white thobe, a neocolonial power whose every move is genocidal. The SAF’s history as the backbone of Bashir’s Islamist security state fades into the background. The Brotherhood networks embedded in the officer corps are airbrushed away. What remains is the familiar morality play of coloniser versus colonised, oppressor versus oppressed, settler versus native. Gaza is replayed on the banks of the Nile, and Islamist imperialists are once again portrayed as “indigenous” to the land.

The gold story offers a perfect case study of how this works. Qatari-aligned outlets and influencers accuse the UAE of stealing Sudan’s gold because it exports large volumes of gold despite having no mines of its own. This insinuation ignores the basic structure of the global gold trade. Switzerland, Hong Kong, and Singapore are also major exporters with no domestic production, because they serve as hubs for import, refining, storage, and re-export.

The real question is not if a non-producing country exports gold, but whether or not its refineries and traders enforce responsible sourcing. In recent years, the UAE has introduced a national “UAE Good Delivery” standard and due-diligence regulations on responsible gold sourcing, along with anti-money-laundering rules that allow regulators to fine or suspend non-compliant refineries. I saw this up close working with jewellery producers in Dubai’s gold and fine-jewellery sector, and I found the rules so strict that I could not even experiment with gold plating. None of this makes the UAE’s gold market especially virtuous, but it does mean the cartoon of a pirate emirate looting Africa is propaganda, not analysis.

At the same time, UN experts and investigative journalists have documented flights linked to Emirati entities supplying arms and logistics to the RSF via an airstrip in Chad. Abu Dhabi insists these flights were delivering humanitarian aid. Since the war began in April 2023, the UAE says it has provided about US$600 million in humanitarian aid to Sudan and its neighbours, and roughly US$3.5 billion over the past decade, channelled largely through UN agencies and international NGOs. In March 2025, Sudan filed a case against the UAE at the International Court of Justice alleging “complicity in genocide”; the ICJ declined to hear it on jurisdictional grounds, citing the UAE’s reservation to the Genocide Convention. When I spoke to Sudanese experts, the UAE’s role in arming the RSF was not dismissed, but it was placed in this wider context of a state hedging militarily and pouring in aid, as it did in Gaza.

That context matters even more because the UAE was one of the earliest and most aggressive anti-Islamist states in the region. Long before most Western capitals were willing to name the Muslim Brotherhood as a threat, Abu Dhabi banned its local affiliate, and in 2014, formally designated the Brotherhood and a range of Islamist organisations as terrorist groups. You do not have to admire every aspect of the Emirati system to recognise that it has paid a steep price for pioneering an explicit anti-Islamist doctrine in the Arab world.

The Qatari/Brotherhood disinformation campaign flattens all of this into caricature. Abu Dhabi becomes the main villain. The SAF and their jihadist allies are recast as righteous resisters. The RSF becomes the sole genocidal force. Sudanese civilians are framed exclusively as victims of Emirati scheming. This narrative launders the SAF’s record, punishes Abu Dhabi for normalising relations with Israel, erases Sudan’s own Arab Islamist colonial project, and primes Western progressives, already suspicious of nondemocratic Gulf monarchies, to take positions that strengthen the Islamist axis.

Seen through this lens, Israel’s decision to block a Sudan protest in front of the UAE embassy is best understood as a recognition that the same Islamist networks orchestrating the propaganda war against Israel are now targeting the UAE, a key pillar of the new regional order. To dismiss this as mere protest restriction is to ignore how Islamist movements have learned to weaponise democratic language, turning the rhetoric of rights and civil liberties into a shield for the most illiberal of agendas.

One of the most cited sources in this campaign is the Humanitarian Research Lab (HRL) at Yale’s School of Public Health. Its satellite analysis of atrocities around El Fasher has been crucial in documenting RSF abuses and likely mass killings. My concern is not that HRL is fabricating evidence, but that its findings are being selectively amplified in a Qatari-aligned information ecosystem that has spent a decade demonising the UAE for breaking with Islamists and normalising with Israel. Al Jazeera’s coverage, for instance, leans heavily on HRL reports to tell a story in which RSF and the UAE absorb almost all the blame, while Iran’s axis and Sudan’s Islamist networks receive far less scrutiny.

That selectivity also matters because Yale itself has faced questions about transparency over Qatari funding. According to a 2023 report by the Institute for the Study of Global Antisemitism and Policy (ISGAP), Yale reported just US$284,668 in Qatari support to the US Department of Education between 2012 and 2023, while ISGAP estimates, on the basis of public records and contracts, that the true figure is closer to US$15.9 million in gifts, contracts, and in-kind arrangements.

HRL’s executive director, Nathaniel Raymond, has publicly denied that the lab receives any Qatari funding, although he did not respond to my email seeking clarification. My argument is not a courtroom allegation but a structural one: when universities under-report authoritarian funding, and when their research sits at the centre of highly politicised narratives, the burden of methodological caution and disclosure should be higher, not lower. By framing Sudan’s genocide almost entirely as a story of “rogue Emiratis,” with far less scrutiny of Iran’s axis or Islamist movements, HRL’s analysis ends up reinforcing a narrative written in Doha, not New Haven.

@HRL_YaleSPH receives no funding from Qatar, we have no relationship to Qatar, and none of the message below has any basis in fact or applies in any way to HRL. https://t.co/lnL6s4fLS8

— Nathaniel Raymond (@nattyray11) November 6, 2025

ISGAP’s work on the Muslim Brotherhood describes a hundred-year plan for “strategic entryism” into universities, NGOs, professional bodies, and policy circles—a long game to subvert liberal democracy from within. Sudan has been one of its deepest reservoirs. Under Hassan al Turabi in the 1990s, Khartoum hosted the Popular Arab and Islamic Congress, a forum that stitched together Islamist movements from Hamas to al-Qaeda, while the 1991 Brotherhood memorandum found in Virginia laid out the matching blueprint for “civilization jihad” in the West.

These are clear warnings that Western democracies cannot afford to let Brotherhood affiliates, or their media and NGO establishments, set the terms of policy on Sudan or the Gulf. Yet that is what happens when CAIR, an organisation explicitly named in the Brotherhood memorandum as part of its US network, leads a campaign to sanction the RSF and embargo arms to the UAE, and when progressive lawmakers echo Qatari talking points, weakening one of the only Arab states that has made peace with Israel and pursued explicit anti-Islamist policies. This only empowers the forces that want Sudan and the region trapped in permanent war.

IV. Two Khartoums, One Choice

My marriage ended on the same fault line that now runs through Sudan. My ex-husband believed Islamists would bring democracy to the East, and that the “resistance” camp was the only honest vehicle for change. I never shared that belief. I spent years trying to convince him that Jews and indigenous peoples in the region had a right to sovereignty and safety. For him, that meant surrendering power and inherited privilege. For me, it was the minimum condition for peace.

After watching Islamist parties devour every Arab Spring experiment they touched, I told him there would be a civil war in Sudan. The argument followed us to a panel on Edgware Road, where a Sudanese constitutional scholar, a polished product of the old order, declared that quotas for women and marginalised groups “do not work.” I stood up, shaking with anger. “That is entirely false,” I yelled. “The social data show the exact opposite.” The applause came from the women and the Darfuris shoved in the back of the room. My ex-husband’s fury came from the front: “How dare you speak on behalf of Sudanese women. You are a gringa.” That scene was Sudan in miniature: the victims in the back, the gatekeepers in the front, and a system invested in silencing women and minorities to keep Islamist and pan-Arabist supremacy alive.

Sudan now sits between two regional projects as starkly as my life once sat between two futures. If it leans towards the integration camp, towards shared ports and corridors that move trade, data, and people, and towards a normal relationship with Israel, it deprives the Axis of Resistance of a crucial piece of Red Sea real estate and shuts down a historic arms route to Hamas and other proxies.

If, on the other hand, Sudan decays into another Syria, fragmented and jihadist-friendly, it will become a sanctuary for Islamic State, al Qaeda, and Iran-backed militias; a launchpad for cheap drones and costly funerals along the Red Sea; and a standing veto on any post-jihad regional order. Muslim Brotherhood strategists understand this. Islamic State outlets already invite foreign fighters to “migrate” to Sudan and open a new front. Hamas is reported to be rebuilding parts of its supply network there, and Turkish-backed Islamists have found the terrain fertile. For them, a stable, integrated Sudan is a strategic disaster. A broken Sudan is a gift.

Western governments do not have to romanticise Abu Dhabi or the RSF to avoid becoming useful idiots in an Islamist information war. But they should stop outsourcing their moral compass to Al Jazeera narratives and selectively alarmist NGO framing. The SAF is no longer a neutral state institution. It is penetrated by Muslim Brotherhood networks, increasingly aligned with Iran and other anti-Western actors, and reliant on extremist auxiliaries. Treating it as the “natural” interlocutor because it looks like a state on paper is not realism, it is theatre.

Scrutinise the foreign money, the gold, the arms, the proxies, with rigour. But turning normalisation with Israel into a moral stain, and treating the UAE as suspect by default, only hands a propaganda victory to rejectionist theology. The question for the West is simple: Which Khartoum are we prepared to protect and legitimise, and which one are we prepared to watch burn?