Christianity

The Gospel According to Pasolini

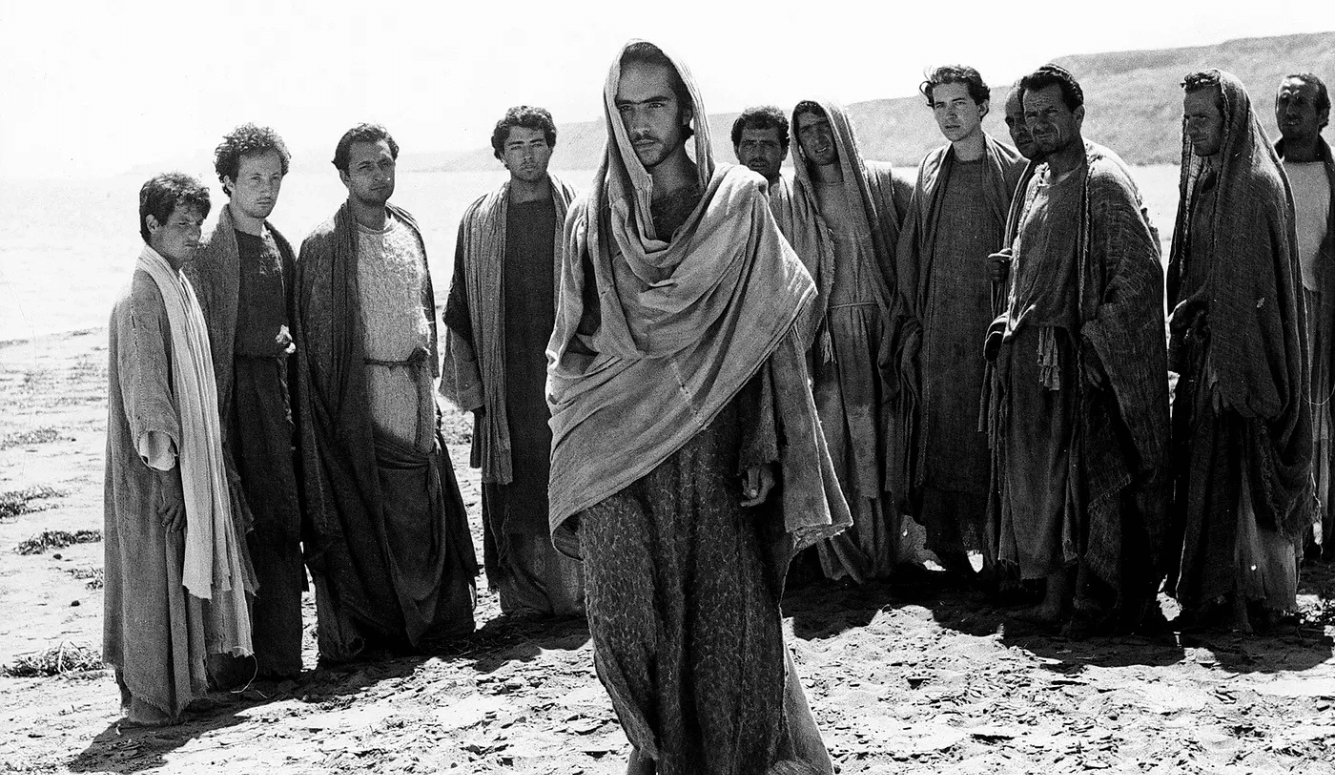

Pasolini's 1964 film reimagines the gospels as fundamentally Jewish stories.

In an essay from her classic collection Against Interpretation (1966), the writer and critic Susan Sontag identifies two contrasting forms of artistic expression: one aims at arousing the viewer’s emotions, while the other provokes more detached engagement that invites reflection. The idea is strikingly similar to Marshall McLuhan’s distinction between “hot” and “cool” forms of media that provoke different styles of audience engagement. For Sontag, however, the difference is more idiosyncratic than rigorously formal. Cinema, the focus of many of Sontag’s essays, can like any medium be made to serve both hot or cool artistic temperaments and either carnal or spiritual ambitions. As she points out, most directors gravitate to one end of the spectrum or the other. Either they are consistently antic, like the Spanish filmmaker Luis Buñuel, or elliptical and reserved like the French director Robert Bresson.

The polymathic Italian writer, actor, and director Pier Paolo Pasolini, however, made masterpieces in both idioms. In striking contrast to earlier and later films that were declared obscene and blasphemous, Pasolini’s The Gospel According to Matthew (1964) is paradigmatic of the detached yet reverent mood that Sontag terms “spiritual style,” which also characterises Bresson’s films. In Pasolini’s take on the gospel, narrative devices that heighten emotion, such as suspense, are unavailable. The outcome is foretold. The plot and dialogue are furnished entirely by the most complete and detailed of the synoptic gospels, the Book of Matthew, which tells a story known to almost every schoolchild.

The Gospel According to Matthew presents an unembellished, literal rendering of the life of Jesus of Nazareth as narrated by the gospel, with a few subtle twists. For instance, the director filmed not in the Levant but in rural Apulia, a remote province in southeastern Italy, with non-professional actors who were mainly local villagers. His unsuccessful attempt to find suitable locations in Israel and Palestine is itself the subject of a fascinating documentary. Pasolini found “Israel much too modern and the Palestinians much too wretched” to serve as convincing stand-ins for Judea in the first century CE.

The British critic Alexander Walker observed that The Gospel According to Matthew “grips the historical and psychological imagination like no other religious film…. For all its apparent simplicity, it is visually rich and contains strange, disturbing hints and undertones about Christ and his mission.” As the great Russian director Andrei Tarkovsky remarked, there is more than a hint of fanatical militancy in Pasolini’s Jesus.

When it comes to the Jewish authorities, the disturbing elements Walker alludes to are more explicit. Herod and the temple priests are depicted as unambiguously corrupt and malevolent. The charismatic dissident, Jesus, the subject of messianic prophecy, represents an intolerable threat to their authority. This view comes directly from the gospel itself, which contains the seeds of what would grow into a centuries-long legacy of Christian antisemitism and persecution of Jews. Likewise Herod’s massacre of the innocents, shown early in the film, contains the roots of the blood libel against Jews. These tropes map directly onto commonplace forms of antisemitism familiar today—up to and including the vogue for so-called legitimate criticism of Israel as exceptionally perfidious.