Politics

MAGA’s Weak Gods

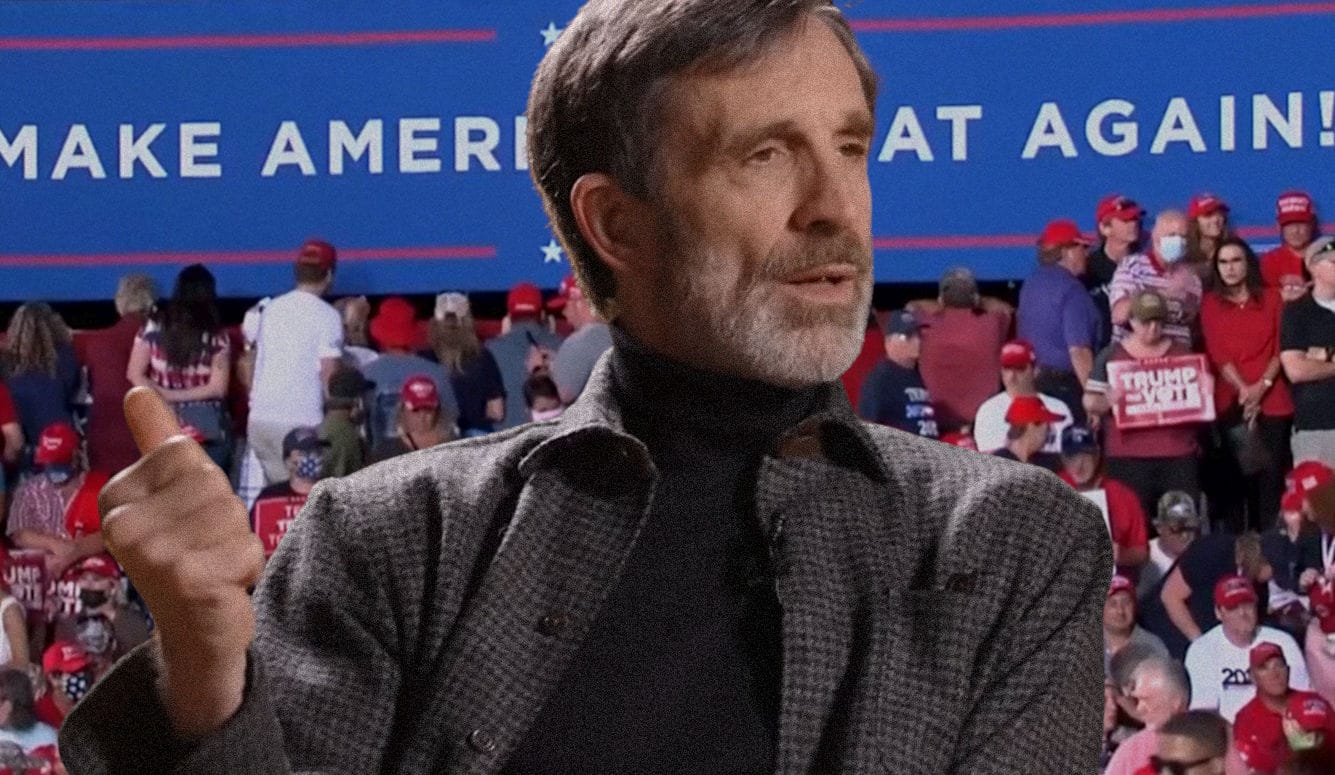

Rusty Reno and the American postliberal revolt against the postwar consensus.

I.

In late 2019, Rusty Reno published Return of the Strong Gods: Nationalism, Populism, and the Future of the West. Donald Trump had a little over a year left in his first term, COVID-19 still hadn’t been detected, and the full Russian invasion of Ukraine was still over two years off. After nearly three years of Trumpism, Reno confidently dismissed those journalists who had “collapsed in hysterics” at Trump’s election because they believed “he was an ‘authoritarian’ of one sort or another.” About a year later, Trump attempted to overturn an election he had lost decisively to Joe Biden.

Reno’s central argument in Return of the Strong Gods is that the true authoritarian threat is posed by a “post war consensus” that persisted throughout what he describes as the “long twentieth century.” According to Reno, that consensus is defined by what it opposes—it is “anti-totalitarian, anti-fascist, anti-racist, and anti-nationalist.” If a political movement is going to be driven by what it resists, it could do worse than the above. But Reno believes its architects and stewards actually began a process of civilisational destruction:

…our societies are dissolving. Economic globalization shreds the social contract. Identity politics disintegrates civic bonds. A uniquely Western anti-Western multiculturalism deprives people of their cultural inheritance. Mass migration reshapes the social landscape. Courtship, marriage, and family no longer form our moral imaginations. Borders are porous, even the one that separates men from women.

This is a fairly conventional conservative critique of modern liberal society, but what makes Reno’s argument different is its outright hostility to liberalism. It’s possible for a liberal to agree with Reno about the downsides of globalisation or the pointless social division created by identity politics. But Reno’s contempt for the postwar consensus—liberal democracy as it has existed since World War II—places him firmly within the postliberal tradition on the American Right. This is not a new phenomenon, as Matthew Rose demonstrates in his brilliant 2022 history of the movement A World after Liberalism: Five Thinkers Who Inspired the Radical Right. But the mainstream success of postliberalism is new, and it has been rapidly gaining momentum in recent years.

In this sense, Reno’s book was prescient. He describes the “strong gods” he believes will ascend from the wreckage of liberalism like this:

The strong gods are the objects of men’s love and devotion, the sources of the passions and loyalties that unite societies. They can be timeless. Truth is a strong god that beckons us to the matrimony of assent. They can be traditional. King and country, insofar as they still arouse men’s patriotic ardor, are strong gods. The strong gods can take the forms of modern ideologies and charismatic leaders. The strong gods can be beneficent. Our constitutional piety treats the American Founding as a strong god worthy of our devotion. And they can be destructive. In the twentieth century, militarism, fascism, communism, racism, and anti-Semitism brought ruin.

The strongest god for Reno is God Himself. When Reno claims that “truth is a strong god,” the truth he has in mind is that of his church (Reno is the editor of First Things, which describes itself as “America’s most influential journal of religion and public life”). A central problem with Reno’s argument is that the “strong gods” of religious tribalism and dogma actually weaken societies—particularly large and diverse societies like the United States. There will never be agreement on which religious beliefs are correct, which is why religious conflicts have been a permanent feature of human life for millennia. The death and destruction caused by these conflicts—particularly the European Wars of Religion in the 16th, 17th, and early 18th centuries—were major motivations for the Enlightenment, which is why liberalism deliberately seeks to avoid inflaming many of the “passions and loyalties” Reno is so attached to.

But the threat posed by the strong gods goes beyond religious dogma, oppression, and violence. Throughout the book, Reno acknowledges that fascism and communism are the clearest examples of what happens when strong gods like nationalism and belief in a transcendent “purpose” to history run amok. Historically speaking, liberalism has proven to be much more resilient than any of the strong gods Reno venerates. This is a fact Reno implicitly concedes when he writes that a “powerful consensus about the open society” must be overcome. It’s quite an admission for Reno to note that “strong gods” are to blame for fascism and communism, while Western democracies like the United States have been guided by a “consensus” around pluralism, openness, and liberalism which coincided with a period of unprecedented power and prosperity.

The strong gods of nationalism, fascism, and leader-worship led Germany and Japan to ruin in World War II, and both societies rapidly emerged from this self-inflicted destruction when they adopted Western democratic models of governance. It would be 41 years before East Germany and former Soviet states in Eastern Europe would bury the strong god of communism, but they were rewarded with historically unprecedented international integration, economic growth, and political freedom. A 1949 collection of essays by anti-communist intellectuals including Louis Fischer, André Gide, Arthur Koestler, Ignazio Silone, Stephen Spender, and Richard Wright was appropriately titled The God that Failed.

What Reno describes as the “weak truths” of secular liberalism—contingent truths that can be questioned and debated instead of imposed from above—are actually a source of strength and endurance. Reno has a special loathing for Karl Popper’s 1945 book The Open Society and Its Enemies, one of the essential works of postwar liberalism which was written at a time when the strong god of fascism threatened to crush Europe. Popper opposed the strong gods which have for centuries guarded the gates of what he calls the “closed society.” This society is characterized by tribalism, mysticism, and authoritarianism—features in perpetual conflict with the pillars of the open society: individual rights, reason, and democracy. Popper is known for his scientific work—particularly his argument that the strength of a truth claim rests on its falsifiability. Reno believes this position amounts to “tossing out nearly all of what the West has regarded as religiously, culturally, and morally foundational.”

The compatibility of Popper’s ideas about falsifiability and the scientific method with liberalism is another testament to liberalism’s strength. Reno views the rejection of comfortable certainties about our place in the universe and other “foundational,” unfalsifiable truths as an abandonment of the strong gods that hold society together. But this rejection has led to many of the greatest scientific breakthroughs—from the Copernican Revolution to the germ theory of disease—that have enriched our understanding of the universe and enabled human flourishing on a much greater scale. The rejection of a single “foundational” set of truths has been a powerful engine of social progress—from the Enlightenment resistance to the divine right of kings (which was integral to the founding of the United States) to the abolitionist case against the religious warrant for slavery.

It’s not surprising that Reno despises Popper, since Popper didn’t believe societies should be organised on the basis of divine revelation or any other strong god. As Reno puts it, rather than viewing the state as “metaphysical and sacred,” Popper argued that it is merely “practical.” This is why he called for a “piecemeal” approach to political and social change rather than utopian social engineering. Popper’s political convictions are consistent with his scientific ones. Societies are much better off with systems of government that have institutional error-correction mechanisms built in. There’s nothing more dangerous than religious zealots or ideologues who believe they already know the truth in positions of power.

Instead of striving toward some grand vision—like the struggle to build a dictatorship of the proletariat or secure paradise in the afterlife—the state should be organised around securing rights, freedom, and prosperity for diverse citizens with inevitably conflicting worldviews. Popper’s “theory of democratic control” is more focused on avoiding bad outcomes than pursuing the greatest possible good. The theory isn’t based on a “doctrine of the intrinsic goodness or righteousness of a majority rule, but rather from the baseness of tyranny … it rests upon the decision, or upon the adoption of the proposal, to avoid and to resist tyranny.” Democratic leaders must address the “greatest and most urgent evils of society, rather than searching for, and fighting for, its greatest ultimate good.”

This vision is bound to be unsatisfying for worshippers of the strong gods like Reno, who believe political leaders should be in the business of promulgating eternal truths. Reno says Popper “neutralizes the strong god of truth, keeping it narrowly scientific.” Throughout Return of the Strong Gods, he condemns the liberal commitment to what he describes as a “lighter, weaker sense of truth, based on trial and error, pragmatic adjustment, and empirical science.” Reno prefers the heavy, strong sense of truth based on revelation and dogma. He attacks those who believe individuals should be “allowed to forge their own moral outlook and their own worldview.” He continues: “A society lives on answers, not merely questions; convictions, not simply opinions. The political and cultural crisis of the West today is the result of our refusal—perhaps incapacity—to honor the strong gods that stiffen the spine and inspire loyalty.”

Western liberal democracy has only survived because it rejects the view that some people have a monopoly on truth that can be foisted upon everyone else. Like other postliberals, Reno thinks he has all the answers. Unlike liberals who recognize that there will never be universal agreement on how we should live, postliberals like Reno demand loyalty to a static and unquestionable set of beliefs. While this can make their political project more appealing to some people in the short run, it’s a fatal weakness over time.