Politics

Against Utopianism

The world is not waiting for our utopian visions to make sense of it and order it. Liberal democracy works when it assumes as much.

Every generation rediscovers the dream of purity, and every generation pays for it. The forms change, but the rhythm remains the same. We’re currently watching a small version of that drama unfold again, this time in the theatre of New York City politics. Zohran Mamdani’s election as mayor might seem like an old story of a political party’s young Turks taking on the old guard. But it is also possible to see a mood shift as that party shifts away from incrementalism and sets its sights on more radical, transformational change. Yes, the old machine could be venal and often shabby, but at least there was an occasional pragmatism to it. The new tone is all religious big-tent revival, the old hymns replaced by slogans of justice and liberation—the saviours of the republic are set to unseat capitalism and usher in the age of the redeemed.

While hardly a national electoral force, the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) have become the symbol of that shift—the break with the art of the possible and the turn toward something more creedal. Support for the movement to boycott, divest from, and sanction Israel, for example, has become something like an article of faith; the land between the river and the sea is to be replaced—never mind how exactly—by a single “democratic” state. While the ideas and ideals are tidy, the world they propose to reorder is not. It is possible to long for justice and still distrust a storyboard that skips the middle chapters. There are precious few stable democracies in the Middle East’s turbulent neighbourhood, and Hamas is not awaiting its liberal awakening. While hope may be a virtue, empty displays of virtue are not.

To see the issue merely as a foreign-policy disagreement is to miss the deeper worldview now animating significant segments of the Left. The wind in the DSA’s sails comes not just from disillusionment with American power abroad, but also from a moral style first incubated on campus and since exported to the broader culture. What began as a fashion on the academic fringe has become the lingua franca of the activist and intellectual class—a mode of moral cognition that treats the social world as ritually unclean, with virtue found in uncovering the stain. For the new clerisy on the Left, problematising has become the only recognised form of intellectual and moral labour. The more thoroughly one unmasks power, the closer one approaches grace. The highest status goes to those who claim to trace domination into ever finer capillaries of social life. It is a moral logic better suited to purification than persuasion.

The trouble with this moral style is not that it sees injustice, but that it needs it—outrage as compass, nourishment, and identity—leaving little room to imagine what might be built in its place. Institutions are to be transformed, traditions transgressed. However, reform and incrementalism are decidedly uncool, and any kind of optimism is even worse. Point out that liberal capitalism—ambivalent, compromised—has nonetheless lengthened lives and lifted hundreds of millions out of subsistence, and you are suspected of insufficient seriousness. Acknowledge that liberal democracy sometimes self-corrects or that market economies, for all their flaws, also feed and innovate, and you are treated as a stooge for the status quo. A partial defence of the West or of “the system” suggests, at best, a failure to read widely enough. At worst, it is a form of stupidity.

There’s an undeniable appeal to this kind of thing. Problematising the “hegemonic” makes you look clever. To feel that you can “see through” what others fail to see is a powerful drug. Like a high-demand religion—think Mormons or Jehovah’s Witnesses—it offers not just moral certainty but meaning. In a world that seems to have lost its senses, this progressive-activist worldview restores order, turning chaos and history into a tidy binary narrative. Few stories are as enduring—or as politically useful—as the one that casts history as a struggle between the pure and the corrupt.

The religious parallels are more than a little uncanny. The critical theorist sits in study, conducting critique, striving to pierce the illusion and glimpse the underlying order of things, to see how power “really” works beneath its many subterfuges. But where the mystic seeks the unity behind appearances, the theorist seeks the source code of domination. Both claim a kind of gnosis, but only one reliably produces compassion.

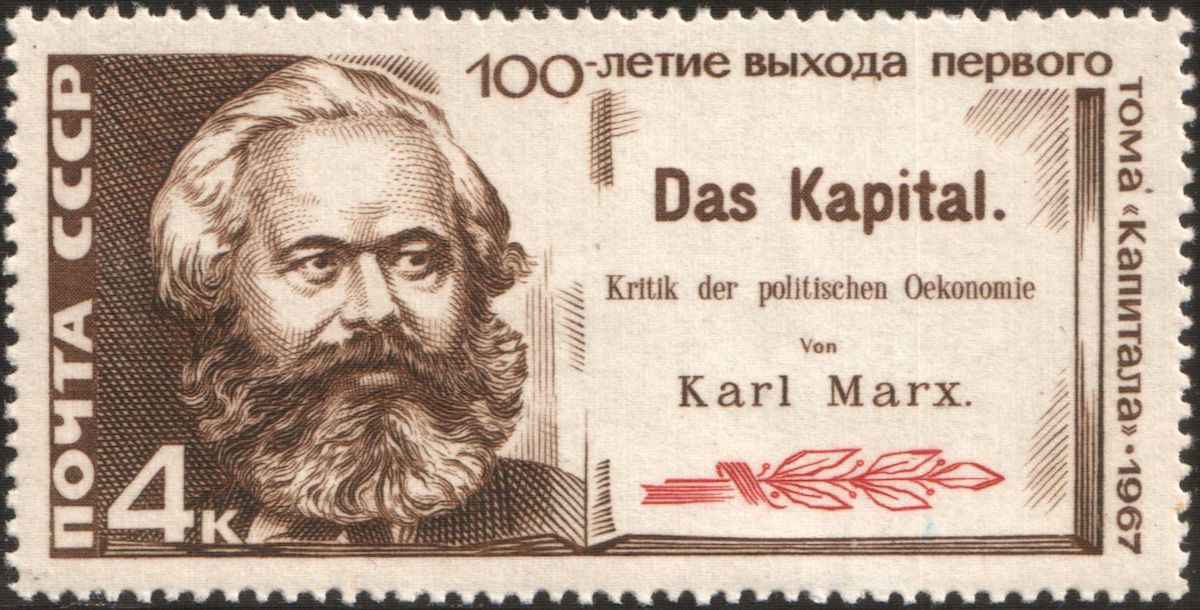

What begins as critique hardens into conviction, and as theory congeals into creed, it generates its own blind spots. One is the elitist nature of the project itself. Marx famously wrote for “the people” from the reading room at the British Library. His was a rebellion of the clerisy as much as of the shop floor. Lenin formalised the awkward tension: the vanguard would raise the consciousness of the worker, so the Bolsheviks would govern them until the workers agreed. It was for their own good and for the good of society.

A century later, the pattern persists. Today’s activists are overwhelmingly credentialed. While their vocabulary is fluent in the taxonomies of oppression, their lives are, for the most part, arranged on the soft furnishings of material comfort they claim to abhor. Their sacraments—confessions of privilege, public denunciations—reflect more a longing for personal purity and redemption than a willingness to sacrifice in ways that might meaningfully change the lives of the working class. As with the communists of old, the people are spoken about, rarely for.

Which leads to the recurring puzzle: why don’t actual voters behave as the professional Left wishes? Why did working-class voters break so strongly for Donald Trump? Why do many Black and Latino voters bridle at progressive scripts? The old Marxist term was “false consciousness.” The newer ones are “internalised oppression,” “white adjacency,” and “people voting against their own interests.” While the vocabulary is new, the conclusion is the same: when the people do not assent, they must have been duped or be of doubtful intelligence.

A second blind spot is historical. The same cohort that can recite the West’s sins without notes often has curiously little to say about the historical ledger of the revolutionary Left. As is well documented, revolutionary regimes in the 20th century killed tens of millions through famine, purges, forced labour, and “re-education.” Mao’s starvation campaign alone swallowed entire provinces. Stalin turned terror into a bureaucratic craft. Pol Pot transformed Cambodia into a killing field, sanctified by the dream of socialist redemption. Cuba’s prisons did not run on metaphors. Even today, Venezuela stands as proof that the socialist utopian impulse survives, undeterred by history’s verdict. These were not accidents. They were what happens when the desire to perfect the world outruns any tolerance for imperfect people, when the thought crime of “false consciousness” becomes an actual crime.

And yet these events occupy a narrow lane in our moral memory—and in the curriculum of many universities. Fascism and colonialism are taught as monstrosities, but those are too often the only bad “-isms” that undergraduates can name. The disasters of leftist utopianism are largely passed over in silence. The Communist Manifesto is still required reading; The Gulag Archipelago rarely is.

There is also a curious paradox at the centre of the anti-Western posture that has become the default of the bien-pensant Left. In trying so hard to “de-centre” the West, activists can’t stop recentralising it. As if reciting from a Chomskyan catechism, they see the United States as a dark occult force underwriting nearly every famine and coup around the world. That this worldview strips non-Western actors of agency is rarely considered. But if every atrocity must be traced to the West, then tyrants elsewhere are reduced to marionettes.

The effect of this Manichean worldview is to reduce our capacity to see the moral complexity and humanity in ourselves. Cruelty and compassion run through every civilisation. Empires rose and fell everywhere throughout history, bringing both great benefits and great suffering. Slavery and other forms of institutionalised cruelty were all but ubiquitous. The West is no exception. But there is something worth acknowledging about a tradition that—however imperfectly, and often under pressure from both conscience and resistance—abolished slavery and dismantled its formal empires. Far from exoneration, such recognition is a way of preserving the possibility that people and polities can learn and even teach.

The warning here is not that we are on the precipice of an American socialist (or fascist, for that matter) gulag. It is that decent people, animated by moral clarity, can talk themselves into nearly anything. Utopian projects—left and right—begin in exaltation and, sooner than anyone expects, require coercion to keep their shape. Sometimes the coercion is “soft”—professional ruin, social banishment. Sometimes it is not.

The 20th century is littered with the corpses of those who disagreed about the way to get to Utopia. Nazis, Bolsheviks, Maoists—different doctrines, similar impatience. All were seduced by purity, by the promise of the quick and easy road to erasing contradiction and contention. For now, the DSA’s utopianism is lighter, and its power is small. Even so, the underlying psychology is familiar and not limited to DSA membership: if you tear down the right structures fast enough, the species will be reborn. The messianic mood remains a throughline.

The antidote to self-destructive utopianism is a politics that accepts ordinary imperfection, the limits of human nature, and the importance of traditions, institutions, and community as buffers against anomie and despair. It embraces a small-“c” conservative approach to social change, grounded in the knowledge that the line between civilisation and chaos is a thin one—requiring moderation, preservation, and humility. It also rests on the classical liberal conviction that power needs fences because none of us is an angel for very long.

It is less a program or political label than a temperament—a return to realism, restraint, and a measure of humility about what politics can accomplish, including the amount of meaning we wring out of them. The world is not waiting for our utopian visions to make sense of it and order it. Liberal democracy works when it assumes as much. It builds guardrails rather than heavens. It prefers second-best policies that are possible to first-best visions that are not. The work ahead is to borrow the occasional moment of moral clarity without swallowing the appetite for domination that so often accompanies it. That balance—moral seriousness without messianism—may be the only grown-up option left.

Utopianism always begins as an awakening. It ends, if it is allowed to run through its phases, as a tyranny of the pure. There is a slower path. It lacks ecstasy and salvation. It is not rough or revolutionary. It can feel like a letdown, particularly to the young and the impatient. It accepts imperfection as the price of freedom. It chooses a decent polity over a redeemed one. History suggests this is the wiser bet. Its lesson is unromantic and, for that reason, trustworthy: whenever we try to storm heaven, we tend to wake up in a very familiar place, counting the costs and wondering how the rope we thought we could use to pull ourselves up became a noose.