Politics

The Middle East Powder Keg

Fragile ceasefires are holding for now, but the volatile region may be headed for another explosion next year.

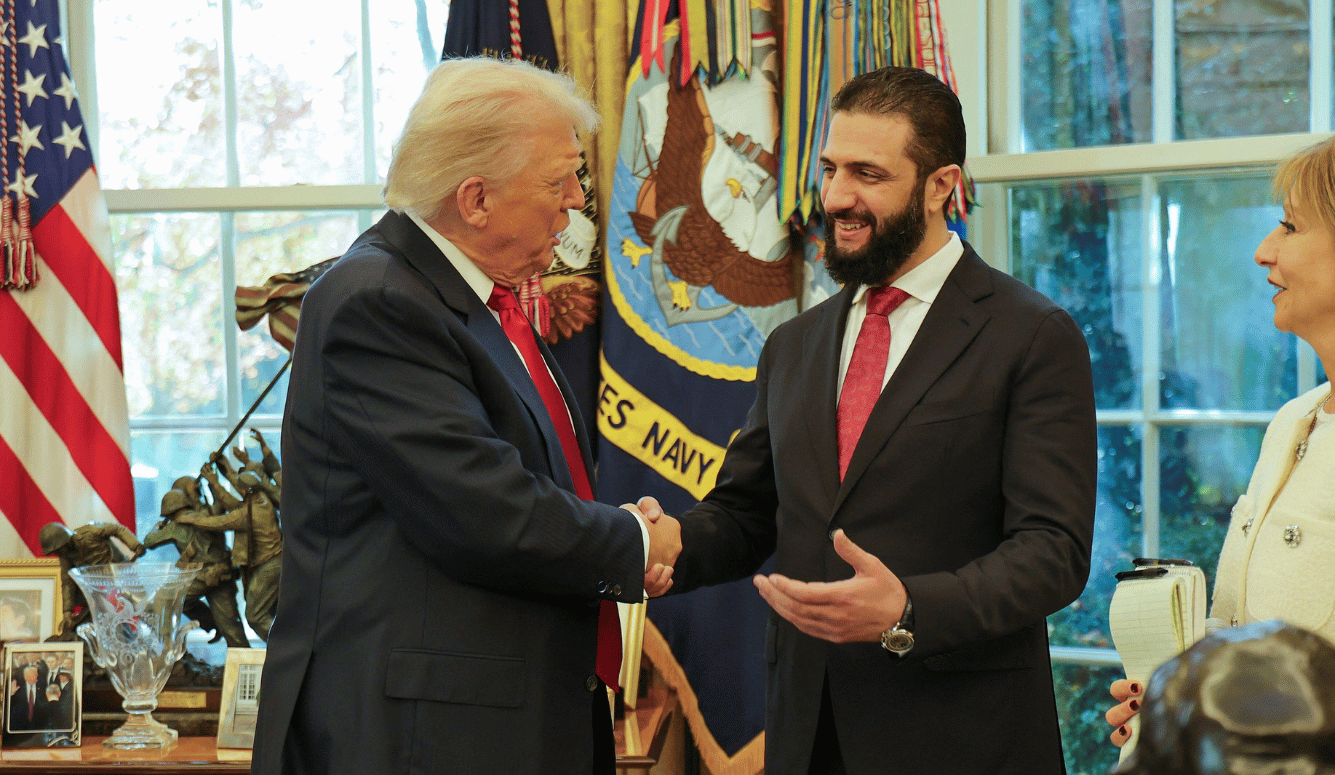

As he is palpably changing America, President Trump is also trying to restructure the Middle East, perhaps as radically as Britain and France did in the wake of World War One. But so far, he has little to show for his efforts, and many local observers believe that the region is headed for a potentially catastrophic explosion next year.

Until now, Trump’s only real successes have been the imposition of two ceasefires—between Israel and Hamas in the Gaza War, which began when the Palestinian Islamists attacked southern Israel on 7 October 2023, and between Israel and Lebanese Hezbollah, which had been rocketing Israel since 8 October 2023 in solidarity with Hamas. That first ceasefire, which is still holding, has seen Hamas release the remaining Israeli hostages it kidnapped on 7 October in exchange for some 2,000 Palestinians from Israeli prisons and the withdrawal of the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) from forward positions in the Strip to a “yellow” line bisecting the Strip, which consists of 365 sq. km or 141 sq. miles. This has left 53 percent of the minuscule territory in Israeli hands and the remainder in the hands of Hamas.

According to the 20-point peace plan Trump announced last month, an “interim” Palestinian government and an “international” military/police “stabilisation” force (ISF), both nominally supervised by an ill-defined multilateral “Board of Peace,” was now supposed to disarm Hamas and “demilitarise” the Strip as the IDF gradually withdrew to a “perimeter” along the old Israel-Gaza border. Then, with funds from oil-rich Arab states, the international community was to begin reconstructing the Strip’s infrastructure and housing, mostly destroyed in Israel’s two-year-long air and ground campaign against the Hamas terrorists.

The plan also vaguely envisioned the establishment of a Palestinian “state” somewhere down the road. (Though France, Canada, Belgium, Britain, and other countries “recognised” that state last September, it is difficult to see how it will become a reality anytime soon.) Trump and Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu had initially hoped that the unfolding process would be accompanied by the resettlement of many of Gaza’s 2.3 million impoverished and traumatised inhabitants in foreign lands. Extreme right-wing Israelis hoped that Jews would begin settling in the Strip’s vacated spaces.