Art and Culture

A Journalism of Deception

A former BBC journalist explains how the corporation discarded impartial journalism and why we need a news revolution.

For the past two weeks, news in the UK has been dominated by the news itself, as the country’s public-service broadcaster has been consumed by controversy. On 3 November, the Daily Telegraph began reporting on the contents of an internal memo it had seen that contained scandalous evidence of bias and dishonest reporting at the BBC. Three days later, the newspaper published the full memo, in which Michael Prescott, an external advisor to the BBC’s Editorial Guidelines and Standards Committee (EGSC), expressed his “profound and unresolved concerns about the BBC,” specifically in relation to the corporation’s coverage of the 2020 US presidential election, issues of race and gender, and the Israel-Gaza War.

The memo was addressed to the BBC’s board of governors, and in his introduction, Prescott wrote:

My view is that the Executive repeatedly failed to implement measures to resolve highlighted problems, and in many cases simply refused to acknowledge there was an issue at all.

Indeed, I would argue that the Executive’s attitude when confronted with evidence of serious and systemic problems is now a systemic problem in itself—meaning the last recourse for action is the Board.

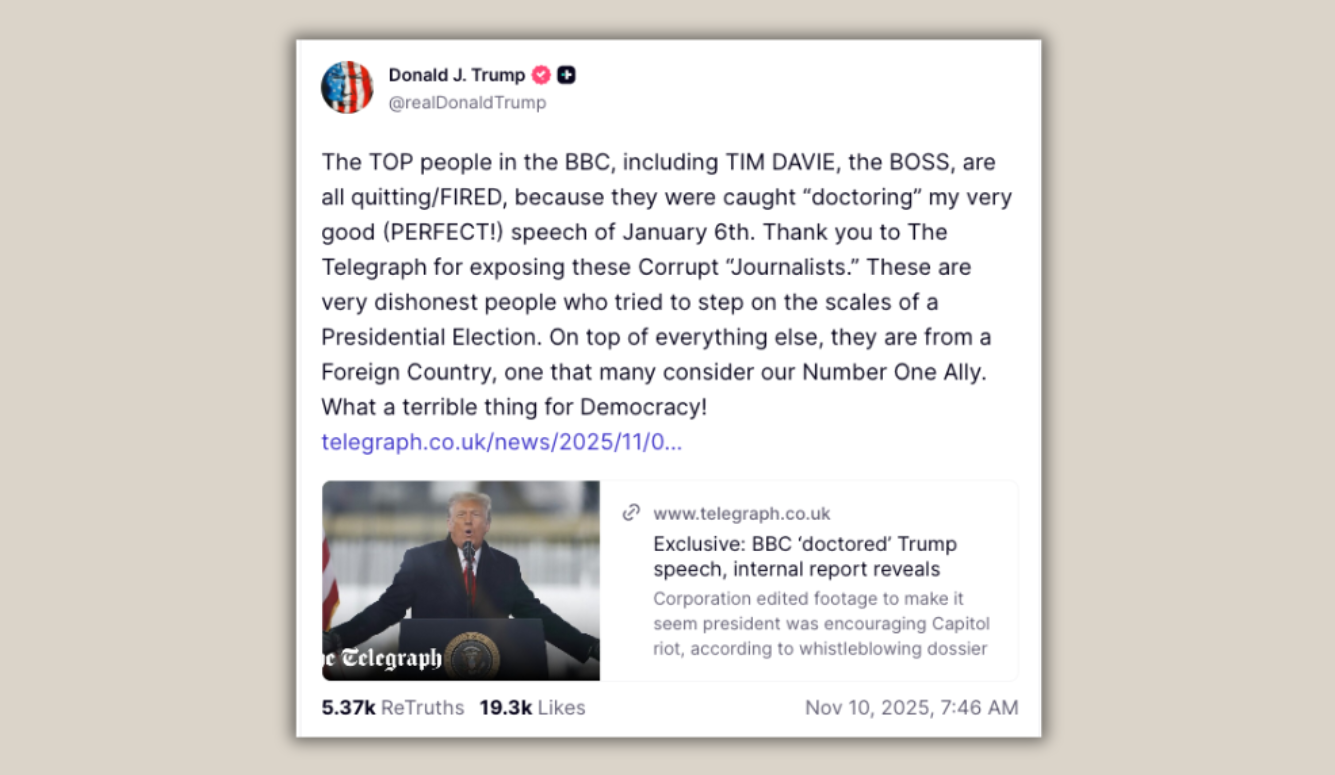

In an interview with GB News the day after the contents of the memo were first reported by the Telegraph, Conservative Party leader Kemi Badenoch declared that “heads should roll.” Finally, on 9 November, they did when director general of the BBC, Tim Davie, and the CEO of news, Deborah Turness, both resigned. US president Donald Trump responded to this news with a post on Truth Social, in which he wrote: “The TOP people in the BBC, including TIM DAVIE, the BOSS, are all quitting/FIRED, because they were caught ‘doctoring’ my very good (PERFECT!) speech of January 6th. Thank you to The Telegraph for exposing these Corrupt ‘Journalists.’ These are very dishonest people who tried to step on the scales of a Presidential Election.” He has threatened to sue the corporation for a billion US dollars.

It is true that much of the criticism of the BBC has come from the corporation’s private-sector competitors and those on the political Right who have always objected to a publicly funded broadcaster in principle. However, the evidence of bias presented by Prescott is damning enough to justify the outrage of the BBC’s critics by itself. In her resignation letter, Turness attempted to limit the damage by nervously explaining that although “mistakes have been made, I want to be absolutely clear [that] recent allegations that BBC News is institutionally biased are wrong.” It would be naive, however, to take this reassurance at face value because no senior BBC figure would ever admit that the corporation is biased. The BBC exists courtesy of a Royal Charter that requires it to “provide impartial news and information to help people understand and engage with the world around them.” Violation of that imperative would jeopardise the BBC’s unique source of funding.

As a former BBC journalist who now teaches journalism at university, I can tell you that, no, the BBC’s journalism is not impartial, and yes, the corporation is institutionally biased.

As a former BBC journalist who now teaches journalism at university, I can tell you that, no, the BBC’s journalism is not impartial, and yes, the corporation is institutionally biased. This problem is by no means limited to the BBC, but since it is publicly funded by the licence fee—payment of which is compulsory whether viewers like what the corporation produces or not—the charge that it is failing to fulfil its public-service remit is particularly damaging. This crisis could still become an existential threat to the BBC, as Conservative Party MPs call for the licence fee to be discontinued. “Forced purchasing of content through the licence fee, with no consumer choice,” said Ben Spencer, “is an analogue anachronism in the digital age.”

The BBC was not always like this—the roots of the current crisis can be traced to developments at the corporation during the 1990s. These were controversial at the time and it is worth revisiting this history if we are to understand how the BBC got itself into this mess and what can be done about it.

Victorian Journalism

A BBC journalist who arrived from 1955 in a time machine would likely be horrified by the state of BBC journalism in 2025. This doesn’t mean that all journalists in the past were truthful—they weren’t. But they understood that their principal goal was to try to tell the truth as best they could, and this pursuit of truth was structurally protected.

Journalists then understood that the world is volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous, and it is therefore very difficult to know anything with complete certainty. The journalist’s task was therefore to report the facts as accurately as possible, and to separate those facts from opinions. Opinions should be balanced by opposing opinions so that audiences can judge matters for themselves. This is the classical journalistic technique of reporting “who,” “what,” “when,” “where,” and “how.” The question “why” was treated as a categorically different matter because the answer will always be a matter of opinion and conjecture.

This journalistic methodology was inspired by the scientific method—a systematic approach used to acquire knowledge through careful observation and rigorous scepticism. It aimed to minimise errors and biases by relying upon reason and evidence, and by eliminating emotion and prejudice. It was developed during the 19th century based on the values of the Enlightenment, in part as a reaction and antidote to the notoriously corrupt journalism of the 18th century, and to the tribalism of the 17th century that produced bloody religious wars, widespread intolerance, and the burning of heretics and witches.

This high-minded, truth-oriented journalism was pioneered by the London Times under the brilliant editorships of Thomas Barnes (from 1817 until his death in 1841) and his successor John Thadeus Delane. It subsequently became the gold standard for journalism around the world and was widely imitated. In the US, the Chicago Daily News was one of the first newspapers to embrace this method when it was launched in 1876. Its editor Melville Stone compared the new journalistic philosophy to a “witness in court, bound to tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth.” The newspaper that best embodied this approach was the New York Times under the ownership of Adolph Ochs. In 1896, Ochs promised to “give the news impartially, without fear or favor, regardless of any party … and to that end to invite intelligent discussion from all shades of opinion.”

This classical Victorian journalism was also the guiding principle for BBC journalists. In a 1954 essay titled “The Central Problem of Broadcasting,” the corporation’s director general William Haley wrote that the prime duty of a broadcaster should be to “play its part in bringing about the reign of Truth.” All other considerations, he said, such as entertaining audiences, instructing them, or improving their morals, must remain secondary. The search for truth, he said in the Lewis Fry memorial lecture he delivered in 1948, should be “the living Law,” and journalists should “hold fast to it, work under it, test all their conduct by it, and know no other master. For if only we will give undivided allegiance to the True and the Beautiful, the third partner, the Good, will eventually come into its own.”

Charles Curran, who was the BBC’s director general from 1969 to 1977, argued that the job of the corporation was to run an informational supermarket and fill its shelves with a wide choice of fact and opinion. He warned journalists not to fall into the trap of believing that they knew the truth and that it was their job is to enlighten those who did not. Doing so would be to confuse the function of a journalist with that of a priest. The role of journalists, Curran explained, was not to “preach a particular form of conduct. They do not see it as their job to adopt a particular morality as their own and then to use the broadcasting medium in order to persuade everybody else to follow that morality.”

Writing in 1979, Curran was particularly alarmed by what he saw as a new mood of activism that was beginning to appear among younger journalists. “The darkness of intolerance,” he warned, “begins to close in when the torch-carriers begin to want to burn the sinners, instead of to forgive them.”

The Rise of Boomer Journalism

There was, however, a problem with classical Victorian journalism: it tended to be dry and dull. This was a deliberate consequence of the elaborate precautions taken to protect the search for truth. As the BBC’s first television newsreader Richard Baker later recalled, before 1955, newsreaders were not even allowed to appear on television: “It was feared we might sully the stream of truth with inappropriate facial expressions,” he explained. “Instead the viewers saw pictures making the news.” This all changed with the arrival of the Baby Boomers, a generation with radically different tastes, values, and priorities in everything: music, fashion, morality, politics—and journalism.

The Boomers craved excitement in an era of unprecedented peace and affluence, and they came of age during an unashamedly idealistic and utopian decade of cultural rebellion. The Boomers were bored by classical Victorian journalism and its philosophy of impartiality. A new mood was now in vogue—a desire to make the world a better place. Activism and protest were in fashion, and the Boomers favoured a new style of journalism that was committed, angry, and partisan. During the 1960s, writers developed the underground press, an explosive new form of journalism that took sides, embraced radical politics, and unapologetically displayed its contempt for the norms of traditional journalism.

By the late 1980s, the Baby Boomer generation was moving into positions of power and authority in journalism, and in 1992, a new director general arrived at the BBC. His name was John Birt and his self-declared mission was to destroy the old classical Victorian model of journalism and replace it with Boomer journalism. This was hardly a surprise. Birt’s beliefs about journalism were public long before he was appointed to lead the BBC. During 1975 and 1976, he and his colleague Peter Jay wrote five important articles for the London Times. In the first of these, they attacked the traditional journalistic “who, what, where, when, how” framework, which they said represented a “bias against understanding.” The most important question, they argued, and the one that should be answered first, was “why.” This reversed the old journalistic methodology that prioritised factual reporting, and confined explanation and commentary to the editorial columns.

Merely reporting facts, Birt and Jay said, was “unsatisfying”: “With no time to put the story in context, [it] gives the viewer no sense of how any of these problems relate to each other. It is more likely to leave him confused and uneasy.” A report about unemployment, for example, should aim to explain, “the real causes of unemployment.” What was urgently required, they said, was journalism that solved problems. In their second article, they attacked the classical journalistic distinction between fact and “news analysis.” This was, they said, “the basic misconception, the reigning error. It is a distinction without any proper difference.” They also attacked the old journalism for reporting events “as separate stories, each a collection of discrete ‘facts.’” This, they maintained, was wrong because life was not a complex collection of random events, it had patterns that could be analysed and understood by experts.

The primary job of the journalist, Birt and Jay maintained, was to identify and explain a story’s wider narrative. Constructing these narratives would require crack squads of elite reporters who could help ordinary people to understand the world’s problems: “knowledgeable and educated journalists, sometimes working in teams and continuously blending inquiry and analysis, so that the needs of understanding direct the inquiry and the fruits of inquiry inform the analysis.” In their final article, they repeated their view that Victorian journalism was no longer relevant: “In sum, most journalists, including television journalists, work to obsolete and muddled concepts which need to be replaced by the values of a new journalism.”

The revolution that Birt and Jay were proposing horrified experienced reporters. The TV journalist Llew Gardner attacked the authors for their arrogance, their “awful elitism, their smug conviction that they know best and have somehow hit on a truth about television journalism which could only have been discovered by people as wise as themselves.” One of the strongest responses to the Birt-Jay manifesto came from Louis Heren, foreign correspondent of the Times, who lectured them on the value of journalistic humility. The job of a journalist, he said, was to try to find out what was going on and report it as honestly as possible. It was not for journalists to decide what caused the world’s problems, nor preach about how they should be solved. The reason for this, Heren said, is that journalists are often ignorant and have no way of knowing these things:

I realized that very few observers, and indeed some of the participants in the events reported, knew what had really happened. The best one could hope for was to write an honest report, which did not mislead, and leave the rest to further investigation or history.

John Birt’s Mission to Explain

After he assumed the job of BBC director general, Birt lost no time in declaring war on classical Victorian journalism and all those who practised it. He named this project the “Mission to Explain,” the strategic objective of which was ending the separation of fact and opinion. In his autobiography, he describes it as an epic David versus Goliath battle, in which he cast himself as David. Birt objected to the fact that “the BBC’s journalistic tradition overall was descriptive rather than analytical,” and in his memoir, he argues that the corporation was clinging to outdated values: “Many of the BBC’s journalists and programme makers seemed trapped in their West London prisons. Unaware of the swirl of ideas around them.”

This was, Birt observes, a generational clash: “There was a huge cohort—chiefly in their forties or fifties—for whom news and current affairs were a process. They covered and responded to events. They were competent and experienced, but they had long since ceased to think enquiringly. They were in a groove serving time.” Upon his arrival, the pre-Boomers responded with “sullen resentment. ... The centre of the BBC seemed stuck in the 1950s, and, as someone whose values and attitudes had been formed in the 1960s, I stood out. … My modern clothes were obviously a cause of great fascination too.”

Birt flooded BBC News with Boomer journalists, many of whom were parachuted directly into senior positions of power and influence. He recalls that he filled “key slots on the team from both inside and outside the BBC, and—in defiance of BBC tradition—by direct appointment, without formal interview boards. I was certain we had to skip a generation or two to fill the lead management positions.” These new senior journalists all shared his generation’s ethical-political values. They even looked reassuringly like members of the Boomer tribe. One new arrival, Birt reports with approval, looked like “a young, radical university lecturer.”

Birt reinvented journalism at the BBC and introduced a new methodology. Scripts would now be written by senior journalists in the newsroom, and then reporters would be dispatched to shoot supporting interviews and footage. In this way, reality would conform to the pre-determined narrative. In Uncertain Vision, her book about Birt’s BBC tenure, Georgina Born describes a meeting at which Birt told producers he wanted to see far more “scripting and planning in advance.” When he was asked which BBC current affairs shows he liked, he replied, “To be honest, there’s nothing I like.” His implication, she reports, was that the truth of a news story “could be arrived at intellectually.”

Narrative construction and management became the most important journalistic skills. Born reports that older journalists complained of “Stalinist pressures to take the ‘BBC line’ editorially.” And as the news agenda was increasingly worked-out in the office by teams of senior staff, many reporters began to feel uncomfortable. One admitted that he frequently had no idea if the stories he reported were true or not. “It’s bizarre,” he told Born; “you become a kind of virtual journalist, stuck in a bureau reprocessing material and not actually going out and witnessing events, not experiencing what you’re reporting.”

But Birt was happy. He saw himself as a journalistic rock star trashing his hotel room—a radical, destructive force breaking the old rules and smashing ancient taboos. Describing his impact on the older generation of BBC journalists, he wrote with glee, “I was the person who blasted their world apart.”

The last decade of the 20th century saw the pendulum continue to swing towards narrative-led journalism. No one exemplified this trend more than the British celebrity reporter Martin Bell. Bell was the BBC’s foreign affairs correspondent, well-known for appearing on screen in his trademark white suit. In 1997, he published a manifesto of his own in which he followed Birt’s ideas to their logical conclusion. He wanted to see a new type of journalism which he called the “Journalism of Attachment.” Journalists, he suggested, should no longer pretend to be impartial, they should join the fight to make the world a better place. Victorian liberal journalism, he said, was merely “by-standers’ journalism.”

Journalism, said Bell, should be understood as a “moral enterprise” informed by knowledge of “right and wrong.” Journalists should not be neutral, they should ask themselves, “What do we believe in?” The job of a journalist, he urged, was not to report events impartially, but to actively intervene:

In place of the dispassionate practices of the past I now believe in what I call the journalism of attachment. By this I mean a journalism that cares as well as knows; that is aware of its responsibilities; and will not stand neutrally between good and evil, right and wrong, the victim and the oppressor.

Whither Journalism?

As a consequence of these developments, modern BBC journalism now suffers from two major defects. The first of these is the reliance on narrative. Once it has worked out which causes it thinks are good and which are bad, these moral narratives quickly become unchallengeable articles of faith to which group members must adhere. This is dangerous because narrative is such a powerful drug. Human beings are Homo narrans, the storytelling ape. We have evolved to understand the world in terms of moral narratives; good versus evil, us versus them. This powerful, binary way of thinking is a product of our tribal past. As the writer Will Storr explains in The Science of Storytelling:

[A narrative] fits over our unconscious landscape of feelings and instincts and half-formed suspicions and makes sense of it, suddenly infusing us with a sense of clarity, mission, righteousness and relief. When this happens, it can feel as if we’ve encountered revealed truth and our eyes have suddenly been opened.

In the context of a newsroom, this makes journalists tribal. They will adopt the same worldview, journalistic groupthink will dominate, and journalism will start to feel like a quasi-religious calling. Questioning the core beliefs of the group will not be permitted. The tyranny of narrative is precisely what impartial, classical Victorian journalism was designed to restrain.

The BBC’s second major defect is that the need to protect the narrative pushes truth-telling into second place. The implications of this shift are profound. The idea that it is acceptable to mislead people if your motive is pure is called pro-social lying and it is well-understood by cognitive psychologists. In modern journalism, pro-social lying means using journalism to influence and persuade audiences to behave in ways that are deemed ethically correct. The Prescott memo has this to say about the BBC’s handling of the trans issue:

[There was] a constant drip-feed of one-sided stories, usually news features, celebrating the trans experience without adequate balance or objectivity.

A typical example was the story of Gisele Shaw, a gushing tale of a transgender wrestler who felt “liberated” by coming out.

This story, posted on March 15th, 2023, glossed over how the wrestler, who is a biological male, had repeatedly won trophies by competing in women’s competition.

The Board might take note that the one undisputed run of ground-breaking journalistic excellence in this space was that of Newsnight’s Hannah Barnes, who went on to author the seminal book about the medical treatment and mistreatment of “trans children.”

Her work might well now not be possible at the BBC, given the culture I describe above combined with changes at Newsnight and the lack now of any programme-specific reporters.

In practice, this is indistinguishable from propaganda, and it turns journalists into de facto media activists. In this one-sided journalistic culture, impartiality is dismissed by celebrity journalists as “both-sides-ism.” The result is a journalism of deception that supports what Prescott calls “an overly simplistic and distorted narrative.” His memo sets out compelling evidence of widespread “unintended editorial bias” that prevents audiences from properly understanding complex issues. “The BBC,” the memo concludes, “needs to accept it has systemic issues, only then can the process properly begin to fix the problem.”

The real problem for the BBC is that it is held captive by a Royal Charter that obliges it to be impartial when it is not. One solution, therefore, would be to scrap the Charter and allow the BBC to be as openly opinionated and biased as any other broadcaster. Another option would be for someone to carry out a counter-revolution at the BBC similar in scope and scale to Birt’s revolution of the 1990s, only this time, the goal would be to restore classical Victorian journalism and a commitment to facts.

It is unlikely that either of these things will happen soon. A Labour government is not about to end the licence fee model or overhaul the Royal Charter, and the BBC is not about to return to the dry and dull reporting that will make its pursuit of viewers even harder in an already fiercely competitive marketplace. Instead, after much soul-searching, things will probably continue as they are for the time being. We should not pretend that the status quo is satisfactory. To the contrary, it is incoherent and confused. And as journalism continues to evolve, it will be for all of us—for society—to decide what sort of journalism we want. Because, ultimately, we get the journalism we deserve.

This essay was adapted from the author’s book Truthphobia: How the Boomers Broke Journalism.