Arts and Culture

Requiem for a Zine

The zine community was a haven for all types of free-thinking artists, misfits, and heretics—until online mobs turned it into just another bastion of social-justice groupthink.

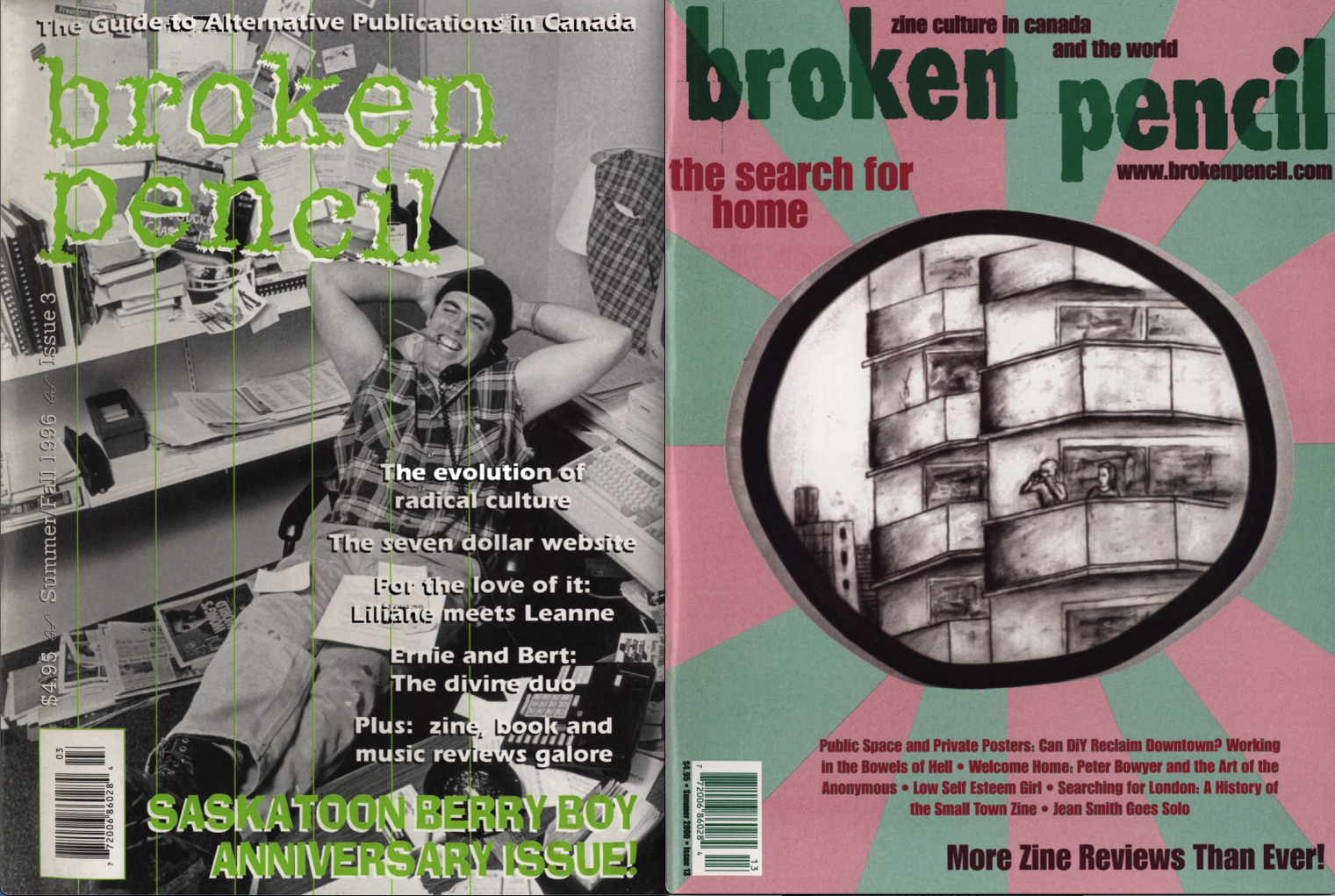

In the fall of 1995, a friend and I started a Toronto-based zine called Broken Pencil. It was an act of joy and hubris. Barely out of college, we railed against the corporate hegemony that controlled the commanding heights of culture, viewing ourselves as part of the “resistance.” I was an emerging writer and reader of the obscure who loved unearthing anything that was unsettling, nonconforming, and weird. We found the stuff we liked and put it in our magazine, hoping to share a different kind of art with the world.

If you aren’t (at least) middle aged, the word “zine” (pronounced zeen) might look like a typo. A traditional zine of late-twentieth-century vintage was a mini-magazine made by hand and reproduced via photocopier. Imagine six pages of standard 8.5” x 11” printer paper folded in half horizontally, and there’s your twelve-page zine. (Another popular format featured a page of paper turned via folds into a tiny, eight-page booklet.) After being Xeroxed (a word we used back then) a few dozen or hundred times, they’d be mailed out to fellow zine enthusiasts (who often published their own zines), handed out at weirdo band nights, or just left lying around at record stores. Publication schedules tended to be erratic, and many zines lasted only a few issues.

The line between zine and conventional magazine was always a little blurry. The larger, more professionally formatted zines had bigger print runs, but they retained the same zine tradition of gonzo content and radical editorial independence. Broken Pencil, which published its last edition in 2024, fell into the larger category. In form, it looked like a standard-size magazine with a glossy cover. But its innards consisted of cheap newsprint. (And even on the cover, we economised by using only one colour).

We used the offices of the University of Toronto student newspaper for layout and design. During the first few years, I’d pick up newsprint bundles at one printer, the covers from another, then drop them all off at a bindery. I’d stuff the finished magazines into my well-aged Honda Civic and bring them back to whatever basement I happened to be inhabiting at the time. The first print run cost around $1,200.

As you might imagine, most zine makers and readers tended to be young. But I never aged out of it, becoming something of a scholar and archivist of the form as the years wore on.

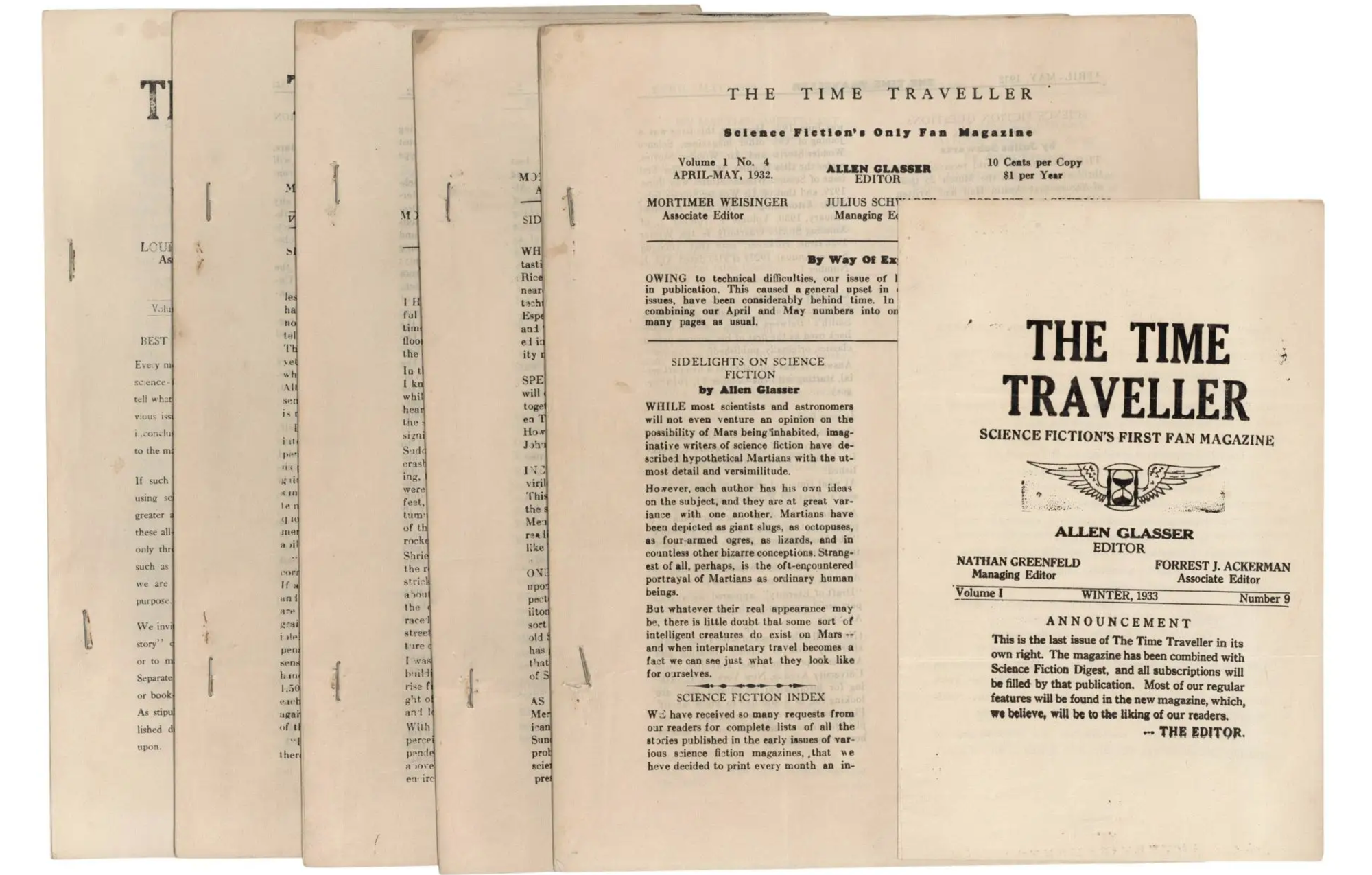

For about a decade, I gave a lecture every year at York University, in Toronto’s northern suburbs, where I’d lay out the medium’s history. I’d start with the covers of classic sci-fi zines from the mid-twentieth century, as the ethos of the amateur mini-magazines to come could be traced to the analogue nerd fandom of the 1940s and 1950s.

The early template was established when dedicated fans of the genre started up what they often referred to as “newsletters.” A 1932 edition of The Time Traveller (“science fiction’s only fan magazine”), produced by New York-based fanzine pioneer Conrad H. Ruppert, featured a short essay assuring us that, just as Jules Vernes predicted the submarine, current science-fiction writers were accurately predicting “splitting the atom” and “harnessing the power of the sun.” There was a list of recently released science-fiction-related movies, including The Island of Dr. Moreau and The Invisible Man. (The latter haunted me when I saw it in the 1980s. While growing up in Maryland, I got my pulp-fiction fix from WDCA Channel 20, whose low-budget “Creature Feature” had, dare I say it, a distinctly zine-like feel. But I digress.)

By the 1940s, there were enough of these amateur mini-magazines that people started wondering what to call them. In Detours, which would become one of the longer running amateur publications, chess-champion-turned-zine-enthusiast Louis Russell Chauvenet proposed “fanzine,” in opposition to, as he wrote, “the un-euphonious word, ‘fanag.’”

The term stuck. And by the 1950s, the Hugos, science fiction’s most prominent awards body, was recognising a Best Fanzine category.

When I started Broken Pencil in late 1995, the world wide web was still in its infancy. And American mainstream fiction outlets were still mostly looking for schmaltzy fare of the type that could be converted into made-for-TV redemption narratives. Like other artistically inspired suburb kids brought up on microwave snacks and whatever moody 1980s counterculture we could find—The Smiths, REM, Echo & the Bunnymen—I saw cultural experimentation through alternative media as an avenue for escape. And I wanted Broken Pencil to connect with others who felt the same way.

I conceived the publication as a kind of meta-zine. We would find tiny zine-y journals that were languishing in obscurity, and then run reviews of their material, while also covering small-press books from indie publishers. My goal was to give zines and books the treatment that Chicago’s Punk Planet and Toronto’s Exclaim had been providing to the independent music scene (which was exploding at the time).

People were sending us self-published zines on everything from gardening to dating to train-hopping. There were comics, essays, collages, and rants. We’d tapped into a shabby but unjustly ignored artistic niche.

Not long after our first issue was published, we started getting mail—plain manila envelopes from all over. People were sending us their self-published zines on everything from gardening to dating to train-hopping. There were comics, essays, memoirs, collages, rants. We’d tapped into a shabby but unjustly ignored artistic niche.

Broken Pencil featured such works as “Don Knotts, Sex Machine” (excerpted from a zine called The Wheel Well), and a short bit from the Alberta zine Limbo, entitled “These Are the People I Picked Up on July 31,” by a cab driver named Peter Stinson. (Several years later, I managed to slip that piece into an anthology I edited called Concrete Forest: The New Fiction of Urban Canada.)

The zines I loved best tended to be esoteric and autobiographical, preferably in a way that redeemed—instead of merely rejecting—the mass culture of the day. I remember a suburban Toronto high schooler named Clare sending me a kind of half-sendup, half-tribute to teen beauty queens, called The Cheerleader. I thought it was a masterpiece and excerpted it in the magazine. A factory worker who went by Sam Geezer sent over an unhinged collage pastiche zine titled Coffee, Smokes, and Radiation. It was a bleak and hilarious take on the kind of manufacturing jobs that, three decades later, Donald Trump would try to resurrect as part of his MAGA project. Then there was Dishwasher Pete, a zine that chronicled Peter Jordan’s quest to wash dishes professionally in every American state. Over twelve years and fifteen issues, Pete washed dishes in diners, retirement homes, and on an oil rig—life in the sudsy undertow of the American dream.

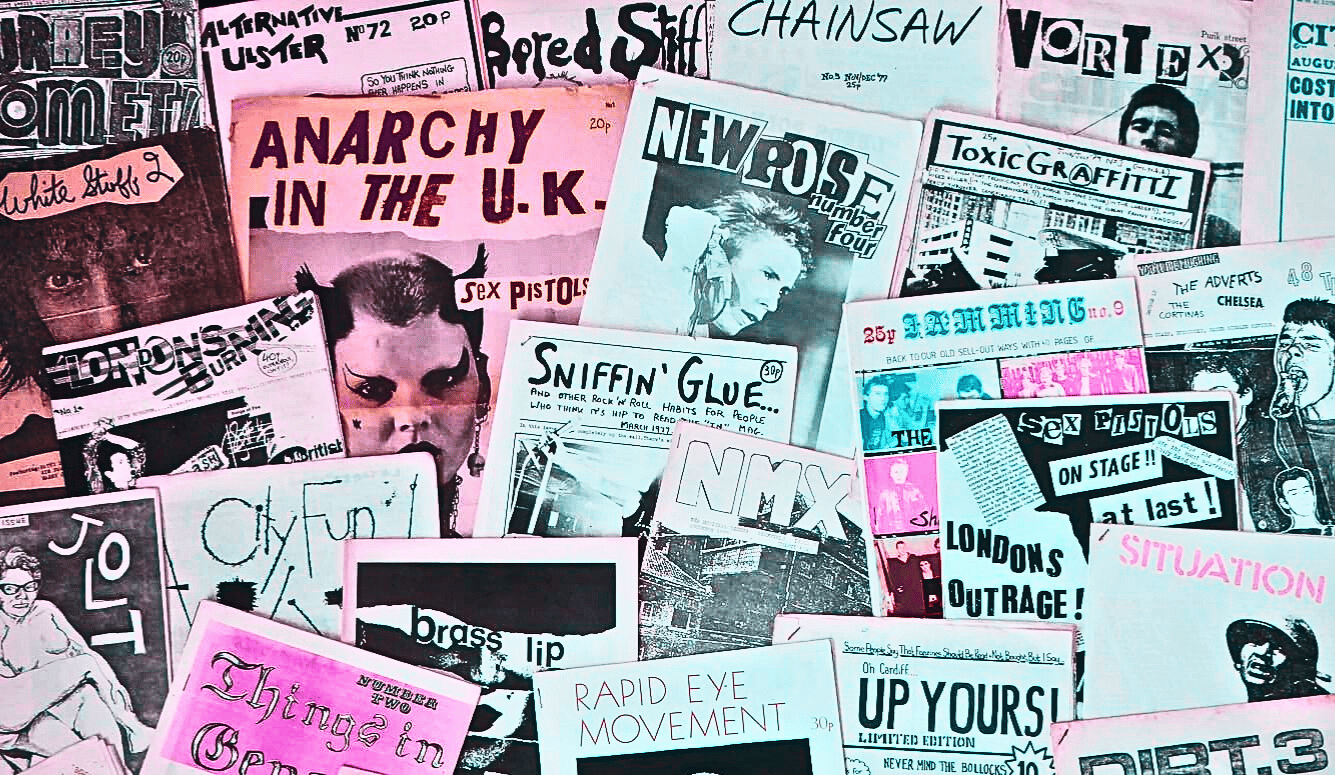

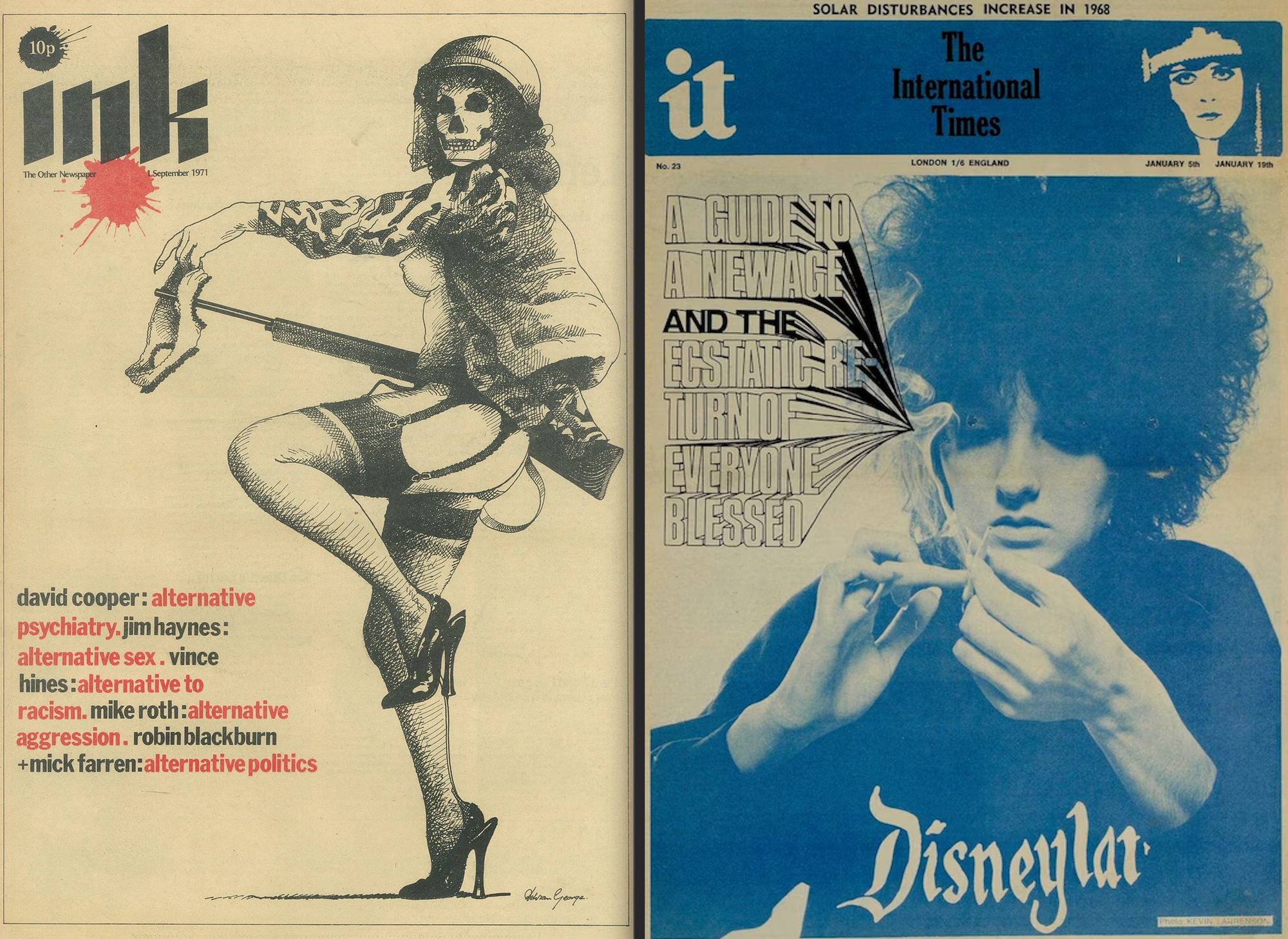

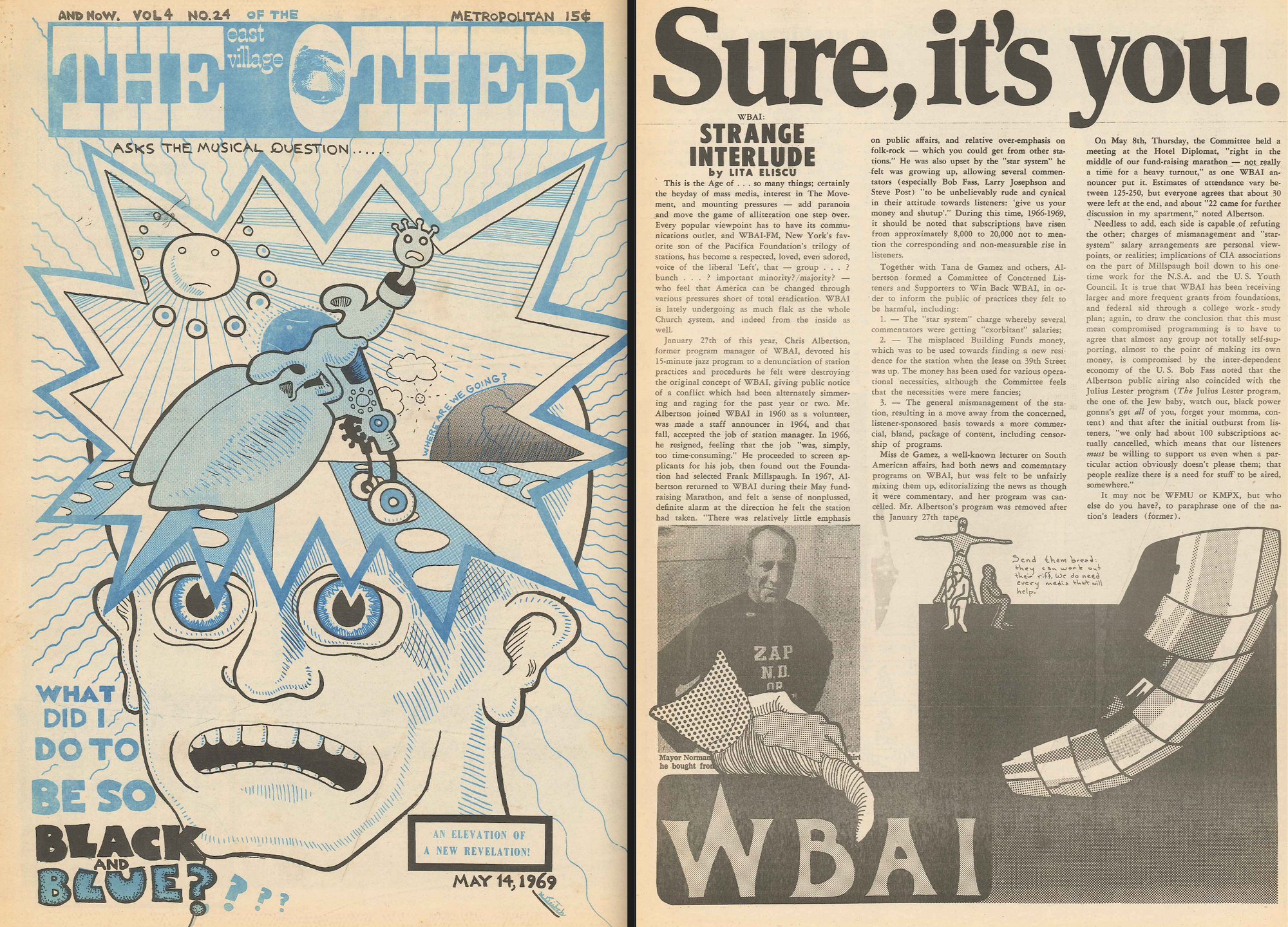

Back on the York campus, I’d follow up the early sci-fi fare with post-war zines rooted in the cultural turmoil of the 1960s. These weren’t connected to any one artistic genre or fanbase. They were often more about pushing boundaries and challenging the stuffy cultural mores left over from the Eisenhower years.

“Underground” was a word that got thrown around a lot to describe this second wave of zines, which showcased the likes of Robert Crumb, Art Spiegelman, Trina Robbins, and, of course, Gilbert Shelton of Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers fame. Scatological, sexual, irreverent, and often disparaged (or enjoyed) as porn-adjacent, the independent comic scene associated with the likes of Zap and Raw would inspire uncountable imitators.

The scene I am describing is connected to the larger 1960s-era explosion of underground media that gave us The East Village Other and San Francisco’s Good Times (published by the commune of the same name). The publications that emerged weren’t zines, but rather countercultural offshoots of the newspaper business, spearheaded by groups with outlier politics—as with the black power movement—that suddenly found they could scratch together enough to pay for the shrinking cost of offset printing. (And even if they couldn’t, there was always the glorious Gestetner machine, which could produce one-colour stencils at low cost.)

While these titles had zine-like aspects, they were distinct from the early science-fiction-originated fanzine movement in an important way: they weren’t channelling the do-it-yourself fandom spirit as a complement to mainstream music, television, film, and literary culture. Theirs was a totalising political project, often revolutionary or even apocalyptic in nature, that aimed at sweeping away mainstream (or, if you prefer, bourgeois) values and power structures altogether.

As anyone who experienced this period knows, the mainstream pushed back through the one medium that no Gestetner-cranking Toronto, Lower East Side, or San Francisco art-house collective could afford: television. On campus, Frantz Fanon may have been required reading. But in the living rooms of North America, life still came with a laugh track, instant-coffee commercials, and an uplifting moral message. Caught between these two poles, fanzines were becoming cultural orphans—too strange for the mainstream, but too esoteric and ironically detached for student revolutionaries.

Though I grew up in the United States, I was Canadian by birth, and returned to Toronto after high school. By the time I finished university, I’d seen enough to realise that the Canadian cultural sector had its own divide. The “independent” literary scene was dominated by sleepy magazines with names such as Grain and The Fiddlehead, at which many an old-stock Canadian editor would commission friends to write or review stories about prairie towns and fishing villages. These tales would expand into books that would, in turn, be praised in further issues.

I, on the other hand, was writing fiction about big-city alienation and the way our manufactured world masked underlying social rot. (My triumph at the time was a three-page short story called “Smell It.”) Little spoke to me in the complacent arts scene that surrounded me.

Shortly after the second issue of Broken Pencil came out, I received a life-changing offer from what was, at the time, an independently owned newspaper serving southwest Ontario, The London Free Press. I’d been working as a delivery driver and part-time concert-hall usher, even as I maintained a boozy after-hours double life as a zine publisher and short-story writer. The Free Press editor offered me $500 for an article on zines—$100 more than I got every week from my delivery gig.

I saw zines as a model for how deep connection to mass electronic culture was seeding new communities that filled the void left by all those bygone bowling-league nights, Tupperware parties, and Elks Lodge meet-ups

I immediately said yes, putting in motion a decades-long career as a non-fiction arts writer. In time, my articles turned into books—including my first, about the clash between pop culture, high art, and alternative/underground culture, We Want Some Too: Underground Desire and the Reinvention of Mass Culture.

At the time, numerous social critics were warning about the breakdown of civic connection in Western societies. (Perhaps the most famous was Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam, whose widely cited 2000 book on the subject would be titled, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community.) Popular culture, particularly TV and movies, came under fire for turning us into passive consumers who stared at screens instead of interacting with others.

I saw things differently. In We Want Some Too, I offered up zine subculture as a model for how deep connection to mass electronic culture was seeding new communities that were filling the void left by all those bygone bowling-league nights, Tupperware parties, and Elks Lodge meet-ups. While television and other forms of mass entertainment inspired a passive, top-down form of cultural participation, zines (and the digital equivalents that were just then beginning to flourish) inspired a more crowdsourced grass-roots approach, breaking down the rigid distinction between corporate producers and consumers.

The first punk zine was put out in 1976 by a London, UK nineteen-year-old named Mark Perry. Its title, Sniffin’ Glue, was lifted from a providential song on the first Ramones record (“All the kids wanna sniff some glue… all the kids want something to do”). Perry was working as a bank clerk at the time. Needless to say, he didn’t find the work particularly fulfilling.

The inaugural issue was just a few pages, tapped out in grammar-challenged fashion on a typewriter that Perry had received for Christmas a few years earlier. The zine wouldn’t last much more than a year. It had to end because, as Perry would later go on to explain, “Punk died” on 25 January 1977, when The Clash signed to a major record label (CBS). Nonetheless, Sniffin’ Glue proved an inspiration to other music fans turned zine editors.

My own initial production methods weren’t much more advanced than the ones Perry had used two decades earlier. In the early days of Broken Pencil, the articles would be printed out in strips and then glued to layout boards using the facilities at The Varsity (where I’d once worked as an editor—alongside John Hodgins, who’d become the first Broken Pencil designer).

Some issues of Broken Pencil broke even. Others would net us a few dollars. It didn’t matter because I had my ‘stupid’ jobs, my writing, and my very own magazine. What else did a 20-something artist need?

After a year or so, we graduated to desktop publishing (as it was then called), which allowed us to design the magazine on computers. (We worked nocturnally, and had to be out by 10am, by which time the Varsity newspaper staff required the premises.) The production process involved hours-long file transfers requiring more than a dozen hard discs. Often, we’d get an error in the middle of things for no discernible reason, and the whole process had to be redone. We kept alert with coffee, cigarettes, and a few other substances we’d packed.

Some issues of Broken Pencil would break even. Others would net us a few dollars. It didn’t matter to us because, as I wrote at the time, I had my “stupid” jobs, my writing, and my very own magazine. What else did an unencumbered twenty-something artist need? I was living by my own punk-rock Mark Perry-style ethos. Rent was cheap, as was beer. All I wanted to do was create things that made everything weirder.

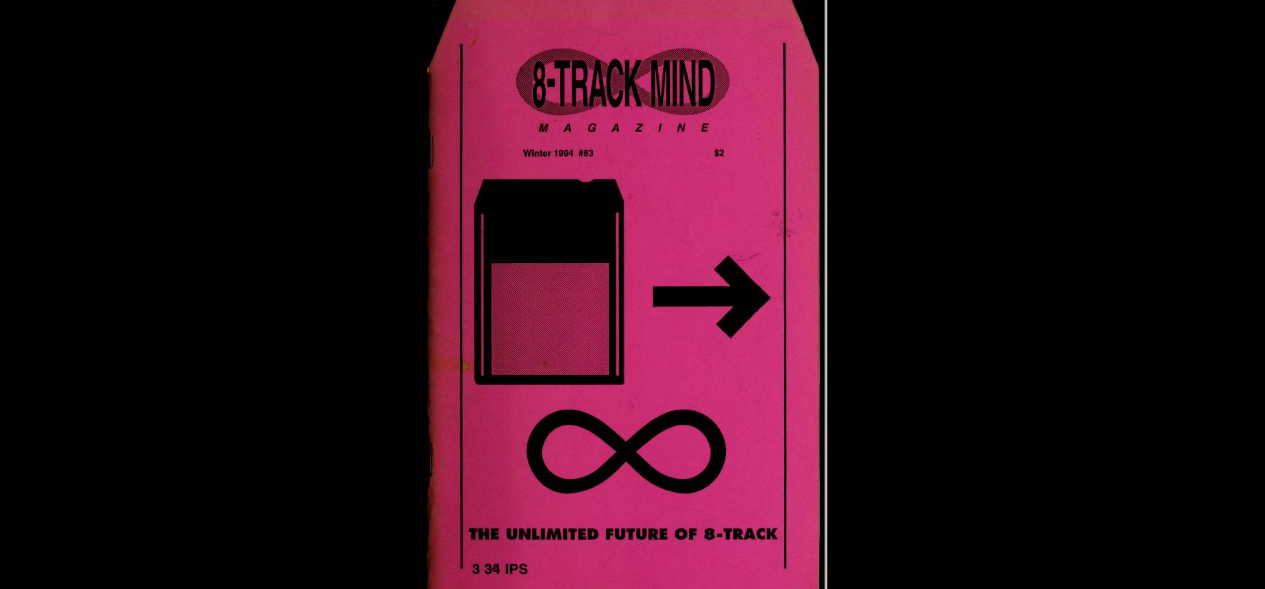

Eventually, of course, the internet revolutionised this entire media landscape—though the process wasn’t as quick (or complete) as you might expect. The San Francisco-based publication Factsheet Five, which put out 100-plus-page issues listing hundreds of zines on everything from 8-Track cassette collecting to the drudgery of low-paying jobs to a miscellany of American murder, stuck around into the late 1990s. Other zines lasted into the 2000s, in part because even small cities tended to have at least one or two surviving independent bookstores (and even record stores, in some cases) where zines could find a niche. (Broken Pencil was sold not just in stores across Canada and the United States, but also at overseas locations of the late great Tower Records, in cities such as Tokyo, London, and Sao Paolo.)

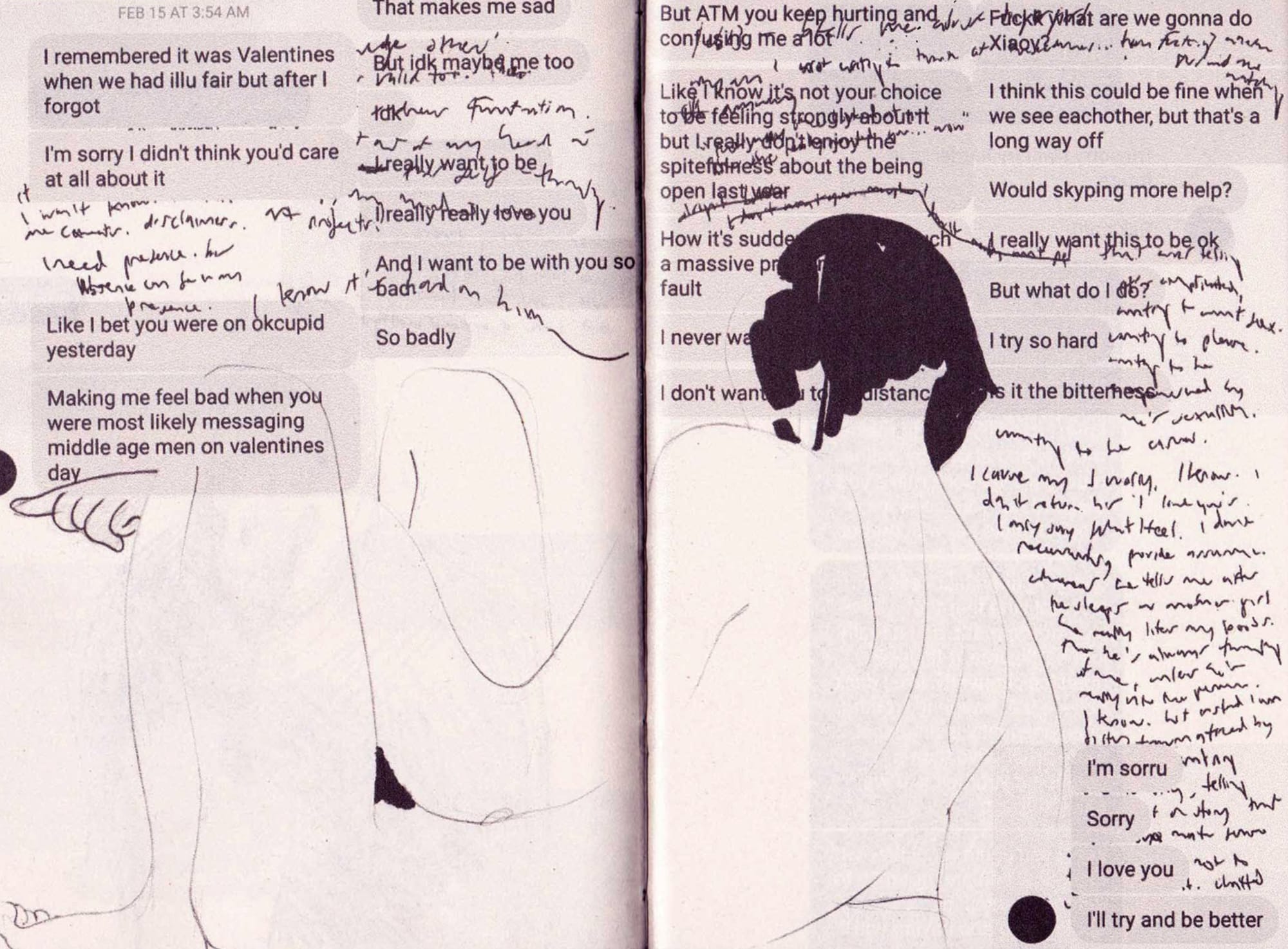

One thing that didn’t change during this crossover era is that zines retained their say-anything confessional character. There were zines about squatting, zines about dumpster diving, zines about breakups, zines about addiction, zines about every possible kind of sex and sexual preference. I remember receiving two mini-compact discs in the mail that turned out to be a his/her audio “zine” consisting exclusively of recordings of people orgasming.

One of the most interesting publications to emerge during this late-stage flowering of anarchic zine culture was Infiltration: The Zine of Going Places You Aren’t Supposed to Go. Written by the mysterious “Ninjalicious” (a Torontonian whose real name was Jeff Chapman), each issue documented a building or other piece of infrastructure that was technically off limits to the public. The closed floor of a hotel, a hidden mothballed subway station, a network of storm drains—Ninjalicious’ access to all these places was meticulously documented. (Alas, Ninjalicious died from cancer in 2005 at the much-much-too-young age of 31.)

Inevitably, however, these subcultures migrated to Myspace, Reddit, Facebook, Tumblr, Medium, YouTube, and the hundred other popular sites that let people tell their stories to the entire planet—a process that was turbocharged by the advent of the iPhone in 2007. In a nod to the times, Broken Pencil introduced coverage of what we started calling “e-zines”—stuff we found on the web that seemed consistent with the zine-y, punk-y paradigm. But after a few years, we gave that up: It was far too vast a world for a magazine to cover, and trying to do so seemed pointless. So we focused on what we did best, reviewing independently printed zines, comics, and books. It was a small niche, but, as we were happy to learn, a loyal one. The (zine) revolution, it turned out, would not be digitised.

There were zines about squatting, zines about dumpster diving, zines about breakups, zines about addiction, zines about every possible kind of sex and sexual preference.

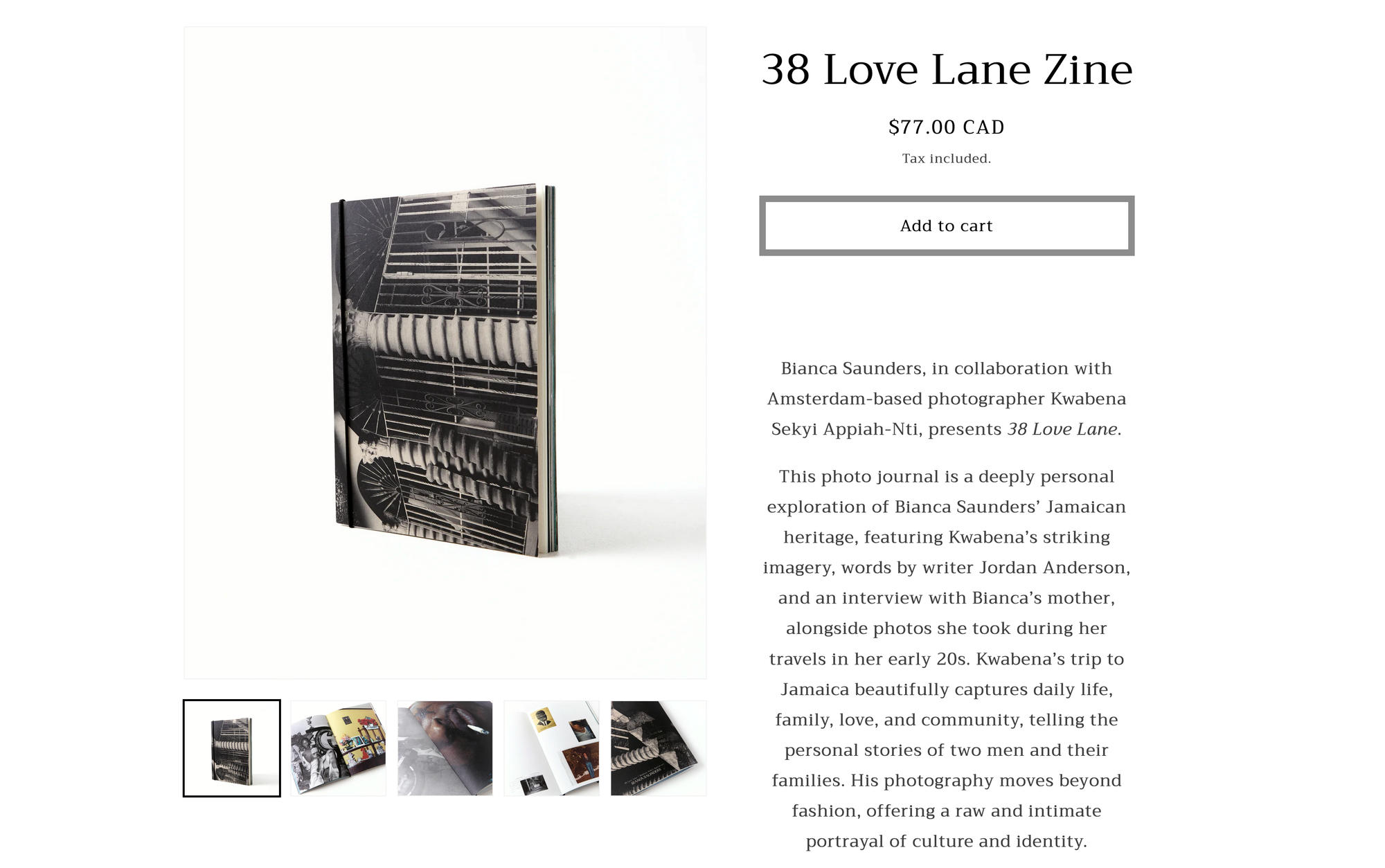

At this juncture, we saw more zines emerging from the fields of visual arts and design—produced by young art students, photographers, and even well-established creators. Previously, there’d been a gulf separating the high-end artist-book subgenre and the world of zines. But beginning about fifteen years ago, I noticed artists making exquisite limited edition handmade books for collectors, which increasingly started showing up at zine fairs. Even to this day, artbook events often namecheck zines as part of the proceedings. Goes the bumpf for this year’s Melbourne Art Book Fair, for instance: “From experimental cookbooks sold by the gram to Southeast Asian zines and large-scale installations, this year’s Melbourne Art Book Fair pushes the boundaries of what publishing can be.”

I get an email about a new “zine” exploring an artist’s Jamaican heritage. The link takes me to information about a 76-page full colour publication “printed on Munken pure rough 120 gsm with a hardback Eco Kraft 300 gsm cover.” It comes complete with black elastic round band wrapper and a $70 price tag. This is an expensive one-off self-publishing project, not a zine. But it definitely has zinesque qualities: For those who never experienced the zine heyday firsthand, the Z-word is now a hipster stand-in for any recherché literary project with a hand-made finish.

In a related (and less welcome) twist, high-end fashion and design creatives have co-opted the Z-word to describe their self-important artsy catalogues. Sold in speciality magazine shops at inflated prices, and extravagantly praised by industry air-kissers as examples of cutting-edge alt-culture, these truly have nothing to do with zine culture. Rather, they’re lavish publications printed on glossy stock and stuffed with professionally produced photography and design.

In 2023, this whole too-precious trend coalesced into a travelling exhibition, Copy Machine Manifestos: Artists Who Make Zines, which showed around the world, including at the Vancouver Art Gallery and The Brooklyn Museum, where the concept was conceived. Naturally, it came complete with its own publication—an exit-through-the-giftshop hardcover book produced by London-based publisher Phaidon. The project adorns pretentious high-art flotsam with a superficial gloss of antique punk nerdom borrowed from zinedom—the conceit being that zines were primitive precursors groping toward the “boundary pushing” (yet also culturally sensitive) works of genius we are supposed to admire today.

Veterans of the zine genre are rightly unimpressed. J.D.s, a Toronto-based gay zine started up in 1985 by Bruce La Bruce and G.B. Jones, was a scream of rage and bitter joy. “All of the horribleness of Toronto compelled us to react against it in every possible way. It pushed us to this breaking point,” Jones would later say of the zine’s impetus. “Its inclusion as an exhibit in Copy Machine obscures its gay raw back-alley sexuality with vague postmodern commentary.”

“‘Queercore’ fanzines aren’t supposed to be catalogued and canonized and analysed to death, for Chrissake,” lamented La Bruce. “They’re supposed to be disposable. That’s the whole point. Throw your fanzines away right now. Go ahead. Photocopied material doesn’t last forever, you know. It fades… dilettantes and librarians… collect and copy and catalogue, and ultimately take credit, for ideas which should be left to those who live them.”

Zines were seen as authentic, and some theorists even tried to shoehorn them into ‘resistance’ narratives starring oppressed minorities.

As much I agree with those thoughts, I have to admit that my magazine continued to benefit, for a time, from this upper-class nostalgie de la boue directed at the zine medium. Broken Pencil was suddenly on the receiving end of a new trend in pedagogy, with teachers assigning students zine-making as part of their coursework. Zines were seen as authentic, and some theorists even tried to shoehorn them into “resistance” narratives starring oppressed minorities. According to one theorist, Adela C. Licona, zines “illuminate the sites, subjectivities, and (discursive) practices of resistance undertaken to generate alternative knowledges, practices, and relations that first imagine and then reconstruct and promote models of social justice and antiracist agendas.”

Some zines apparently even “represent multiply situated, nondominant subjectivities in pursuit of coalition building to address local inequities.” Who knew?

By 2020, many universities across North America were maintaining some kind of zine library. (According to a recently published article, there were at least 170 such collections in the United States alone.) Institutions that just a few decades ago would have treated zines as sub-literary pop-culture-adjacent trash were now mining back issues for insights into “creative acts of queering.” Boston’s NPR affiliate recently exalted zines as “a way for marginalized communities to communicate with one another. For example, the Riot Grrrl feminist punk movement of the 1990s used zines to spread materials covering mental health, racism, sexual and domestic violence and reproductive rights. Zines today are similar in their mission.”

For anyone who treasured zines in the pre-digital era, all of this sounds like a dispatch from la-la land. What we really loved about zines was the chance they offered us to revel in uncensored anarchy. To try to reinvent them as left-prog ideological manifestos that anticipated today’s dogmas and hashtags—“evidence of the conscious search for nondominant, nonnormative discourse,” as Licona puts it—is counterfactual. A deep dive into zine culture would reveal much that is offensive, scatological, pornographic, politically incorrect, and otherwise “problematic,” as the expression goes. It is only by cherry-picking scattered specimens that zines can be reimagined as proto-wokeness.

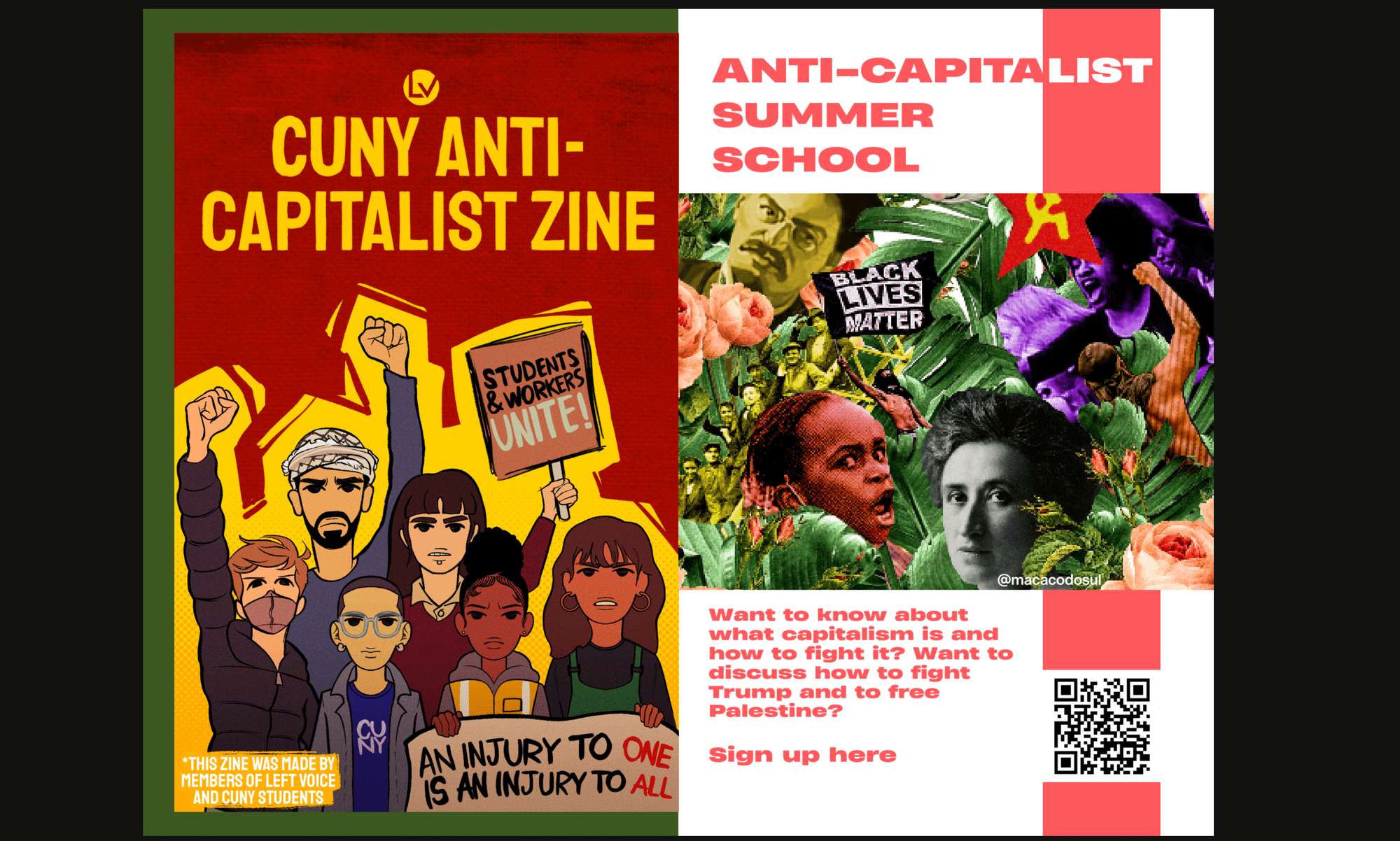

Even more embarrassing are ham-fisted efforts to invent new zines, which actually just consist of doctrinaire progressive agitprop. A recent zine out of the City University of New York, for instance, is titled, Anti-Capitalist Zine. It self-describes as an effort to show that “workers and students united can defeat Trump’s attacks and organize to defeat this imperialist capitalist system.”

Articles include “Creating Antifascist Coalitions in the University and Beyond, What Enrages Me and Gives Me Hope as an Anticapitalist Faculty Member,” a hopelessly maudlin poem called “For the Martyrs” (“We must let the light of their souls guide our rebellion and lead our chariot into the free blue sky”), and a cringe five-paragraph article called “Reflections from a Trans Girl,” which robotically exhorts us to “make the spaces in your life explicitly and systematically trans-affirming.”

Zines are supposed to channel the personal, the obscure, and the hidden. What this Anti-Capitalist Zine instead gives us is the gauzily expressed received wisdom of every identity-obsessed upper middle-class college student.

At Canzine, which I started back in 1995 and which eventually became Canada’s longest running and largest annual zine festival, lit types mixed with drag queens, goths, space-nerds, and anime kids. It was hard to tell if the zine maker you were talking to at any given moment was a rich academic, a punk, a queer activist, or a general-purpose freak tripping on the designer drug du jour.

By the 2020s, alas, this free-for-all atmosphere had been extinguished, largely thanks to activist puritans who scoured the offerings for anything that might be deemed offensive. At one of the final Canzine festivals, a group complained vociferously about a (heterosexual) Crumb-style S&M comic that had been allowed to table. A Vancouver comics and zine festival kicked out a local Jewish artist because a decade earlier she’d done a graphic novel about her time in the Israeli army—which, naturally, made others feel “unsafe.” (The festival organisers, under pressure, later apologised.) Today, there are zine fairs for LGBTQ2S+, for people of colour, for “disabled, chronically ill, Mad, and neurodivergent zinesters,” and for feminists, where everyone feels “safe” because everyone around them has exactly the same opinions. There are still some general zine fairs, but these are now carefully curated so as to pre-emptively extinguish wrongthink.

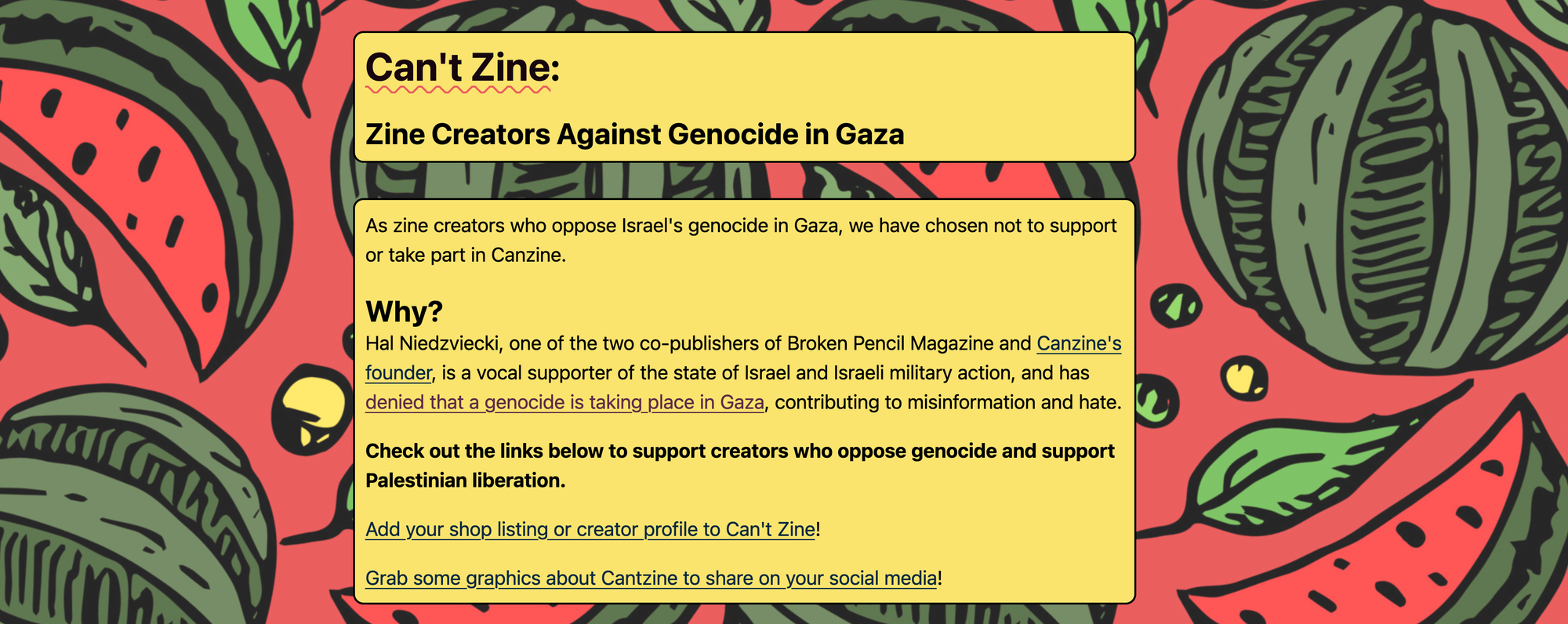

In late 2024, Broken Pencil and Canzine were themselves found guilty of ideological crimes. An anonymously overseen internet campaign was launched demanding that everyone boycott my free-spirited magazine and its fall festival. This included a website called “Cantzine”—Get it?—as well as the obligatory open letter. Apparently, Broken Pencil was being run by the worst kind of person—someone so awful that the whole magazine had to be remade from scratch: a Zionist who “den[ies] the livestreamed genocide and ethnic cleansing of the Palestinian people.”

They were talking about me, of course. Following the 7 October 2023 terrorist attacks in Israel, I’d been loudly expressing my disgust with attempts to demonise Jewish people in the arts and media. Just a few examples included a Canadian small-press publisher posting about their commitment to “Palestine” only days after the slaughter; a coalition of Canadian theatre groups announcing that they were banning “Zionists” from their spaces; and the aforementioned turfing of a Vancouver comic artist for her youthful turn in the IDF. I used my personal platforms to call out these gestures as puerile, often antisemitic, and hypocritical. This was seen as blasphemy by the same clique of ideological enforcers that had, by now, already spent years roaming zine conventions looking for MAGA hats and secret white-supremacist hand gestures.

“Hal Niedzviecki is a ZioNazi!” bellowed Barnard College zine librarian Jenna Freedman on X, before following up with more of the same on her blog. The open-letter signatories not only demanded that I resign, but also insisted that my replacement at the Broken Pencil helm join their anti-Israel boycott and publish “a dedicated issue platforming and supporting Palestinian artists, writers, and zinesters.”

One might suppose that I’d turned Broken Pencil into a right-wing propaganda outlet. In fact, our leftist bona fides were (otherwise) unimpeachable. We’d even recently published a positive review of a zine devoted to the claim that Israel is perpetrating genocide in Gaza. I’d never shared my views about the Middle East using Broken Pencil’s official channels. And while I was listed as founder and publisher, I hadn’t been an editor at the magazine for more than a decade.

My comments were seen as blasphemy by the same clique of ideological enforcers that had, by now, already spent years roaming zine conventions looking for MAGA hats and secret white-supremacist hand gestures.

None of that mattered, of course. Advertisers dropped out, and subscribers cancelled. Clearly, Broken Pencil was suppressing the “sites and subjectivities” of Palestinian resistance with extreme prejudice.

Broken Pencil had touched the lives of thousands of zine makers over the years. Many had told me how the magazine had been a source of inspiration and encouragement—often providing them with the only notice their work had ever received. Nonetheless, no one in the community spoke out publicly to oppose the campaign against the magazine. They were all part of the Borg—or, if they weren’t, were terrified of admitting as much.

It was then that it sunk in: An art form founded on wild-eyed say-anything heterodoxy was now just another signal-relay station for social-justice groupthink. Despite being no stranger to left-wing purges and struggle sessions, I was shocked by the eagerness of these people to disassociate from the magazine.

At the time, we’d been planning a feature on a small indie movie based on a Canadian underground graphic novel. It was the kind of film that gets two reviews, opens for three days in a single theatre, and then disappears. We were going to put the movie on the cover—until both the author of the article and the director of the movie demanded that the article be cut entirely, lest their reputations be contaminated by proximity to a wrong-thinking Jew.

In the meantime, a couple of “zine activists” banded together and produced an entire zine about how horrible and genocidal a person I was, titled Really Broken Pencil. (The shop selling it noted that it was available “with donation to Palestinian orgs.”)

I’d had enough. A Canadian zine mob killed what was, to my knowledge, the only magazine devoted to zines left in the world. It was a symbol for what had happened to the entire medium.

The zine community—such as it was—was formed by those who saw themselves as locked in an existential battle with a corporate enemy that sought to turn artists into machine-stamped clones. Yet in the end, that wasn’t the real enemy. The real danger lurked within. Our commune became a cult, appointing guards to oversee the copy machine, lest someone create forbidden material.

It’s a process of creative self-annihilation that’s played out in many artistic spaces over the last few decades. But it has a particular poignancy when it comes to zines, an art form created by heretics specifically because they felt alienated from the dominant public discourse. It was the one space many of us had where we could be authentic.

There are still, and always will be, great zines being made. If you don’t believe me, read John Claytor’s A Comic On the Opioid Crisis in My Small Town, or some of the other specimens that Broken Pencil highlighted in its last few years. But my run curating and promoting these creators is over, as is the era of the freewheeling and unpredictable zine culture that I started a magazine to celebrate.

What will sustain the next generation of creatives who don’t and won’t fit in? This Fall, Broken Pencil and I won’t be involved in putting on a celebration of zine culture, free speech, and independent publishing. There will be no Canzine; nor, as far as I can tell, any other public big-tent event celebrating underground publishing in Toronto, or in any of the other cities where we operated.

That’s bad news for any young artist seeking an audience for his or her work. But it’s good news, I suppose, for the puritans who’ve ruined the medium: What better way to cleanse a room of heresies than to empty it of people?