classics

Fragments Against the Ruins

In his deliberately archaic new rendition of Homer’s epic, Jeffrey Duban takes a defiant stand against the modernisation of classical literature in defence of a disappearing tradition.

A Review of Homer’s Iliad in a Classical Translation by Jeffrey M. Duban; 672 pages; Clairview Books (May 2025).

Jeffrey Duban’s new book Homer’s Iliad in a Classical Translation is obviously a labour of love. No sane person would willingly translate 15,000 lines of ancient Greek poetry into modern English verse without some good reason to do so. Duban seems eminently sane, and highly competent, so we can trust that he has not done this merely on a whim. But countless translations of Homer into English already exist. What is the point of expending so much time and energy on a project that has already been successfully executed more than once? This is a question that every translator of a famous literary masterpiece ends up asking himself, and the answer is rarely self-evident. In this instance it takes some thought to unravel the mystery.

On Translating Homer

The classic introduction to rendering Homer into English is a series of lectures that were delivered by Matthew Arnold in 1860 and published in 1861 under the title On Translating Homer. For today’s readers, these lectures are by no means easy reading. They were written for audiences who knew Latin and Greek, could at least struggle through Dante in Italian, and were at ease with the full range of English literature, including the Homeric translations of George Chapman (completed in 1616), Alexander Pope (published between 1715 and 1726) and William Cowper (published in full in 1791). Chapman and Pope still enjoy a certain name recognition nowadays, but few readers will encounter their versions of Homer outside of a PhD course in English literature.

Despite all this, On Translating Homer rewards the struggles involved in getting through it. The central insight is easy enough to digest:

The translator of Homer should above all be penetrated by a sense of four qualities of his author;—that he is eminently rapid; that he is eminently plain and direct, both in the evolution of his thought and in the expression of it, that is, both in his syntax and in his words; that he is eminently plain and direct in the substance of his thought, that is, in his matter and ideas; and, finally that he is eminently noble …

Arnold wants translations of Homer to be grandly simple and plainspoken, in the way that Dante’s Divine Comedy is. He thinks that the standard English verse line, the ten-syllable iambic pentameter, is inadequate for translating ancient Greek epic poetry, whether rhymed (as in Pope’s version) or in unrhymed ‘blank verse’ (as with Cowper). Instead, Arnold thinks that translators of Homer ought to attempt an English equivalent to Homer’s dactylic hexameter, which features six units of two or three syllables, and thus would have lines of between twelve and eighteen syllables.

Arnold’s entire discussion is intricately complex and subtle, and there is no need to summarise all of it here. Duban appears to have grappled with Arnold and accepted certain of his insights whilst blithely rejecting others. For example, he agrees that a hexameter line is ideal for his purpose, but he uses a regular twelve-syllable iambic hexameter rather than a Greek-style line with a varying number of syllables.

Perhaps the most important disagreement between Duban and Arnold involves the most suitable diction for rendering Homeric Greek into English. Duban does not believe in plainness or simplicity, in part because he sees himself as fighting against an impoverished contemporary literary culture that has simplified language for all the wrong reasons. Also, he regards self-conscious archaism as an essential feature of Homer’s epic poetry and thinks it important to remind English readers of this feature. Duban is not interested in reaching audiences who need to be spoon-fed.

There is nothing else quite like Duban’s translation. Perhaps this is because Homer’s status has recently changed, at least in the English-speaking world. The poet Christopher Logue, who could not read ancient Greek, produced a series of iconoclastic Modernist-style retellings of the Iliad (collectively known as War Music), which were published between 1959 and 2005. Yet even he worked under the assumption that Homer was central to Western culture and enjoyed a prestige unmatched by any other author. Logue could take Homeric authority for granted because he lived in a world where nobody seriously questioned it. Duban, by contrast, is acutely aware that the entire classical tradition is under serious threat of disappearing.

In 1998, the Classics professors Victor Davis Hanson and John Heath published Who Killed Homer? The Demise of Classical Education and the Recovery of Greek Wisdom, one of the best-known polemics in the Culture Wars of late-twentieth-century America. Much of what the authors said about dismissive attitudes towards the classical tradition among classicists themselves seemed far-fetched at the time. Almost thirty years later, it has become obvious that they were not pessimistic enough about classicists’ collective self-loathing. These days, a verse translation of a poem that was composed in the late eighth or early seventh century BC will be met with passive-aggressive side-eye even by professional classicists.

Not only is Classics suffering as a discipline—literature itself is too. American literary culture has been seriously eroded in the twenty-first century, to the point where poetry as an art form is effectively dead. Memoirs and autobiographical fiction have become the dominant highbrow literary forms. Who reads poetry, other than the people who write poems themselves? Whatever might have inspired or provoked Duban to translate Homer into verse, it certainly was not fame or worldly advancement. Things have moved on since the early eighteenth century, when Alexander Pope could become financially independent through translating the Iliad and Odyssey into heroic couplets.

So, why write something that only a handful of people might read?

Homer’s Primitive Qualities

Although Homer is the first real poet in the Western tradition, anyone who has taken the time to study the Iliad and Odyssey recognises that there is little about Homer’s artistry that could be described as “primitive.” He boasts a complete panoply of narrative tools and literary devices at his fingertips. Overall, his technical sophistication and sheer intelligence make Matthew Arnold and his Victorian peers seem effete by comparison.

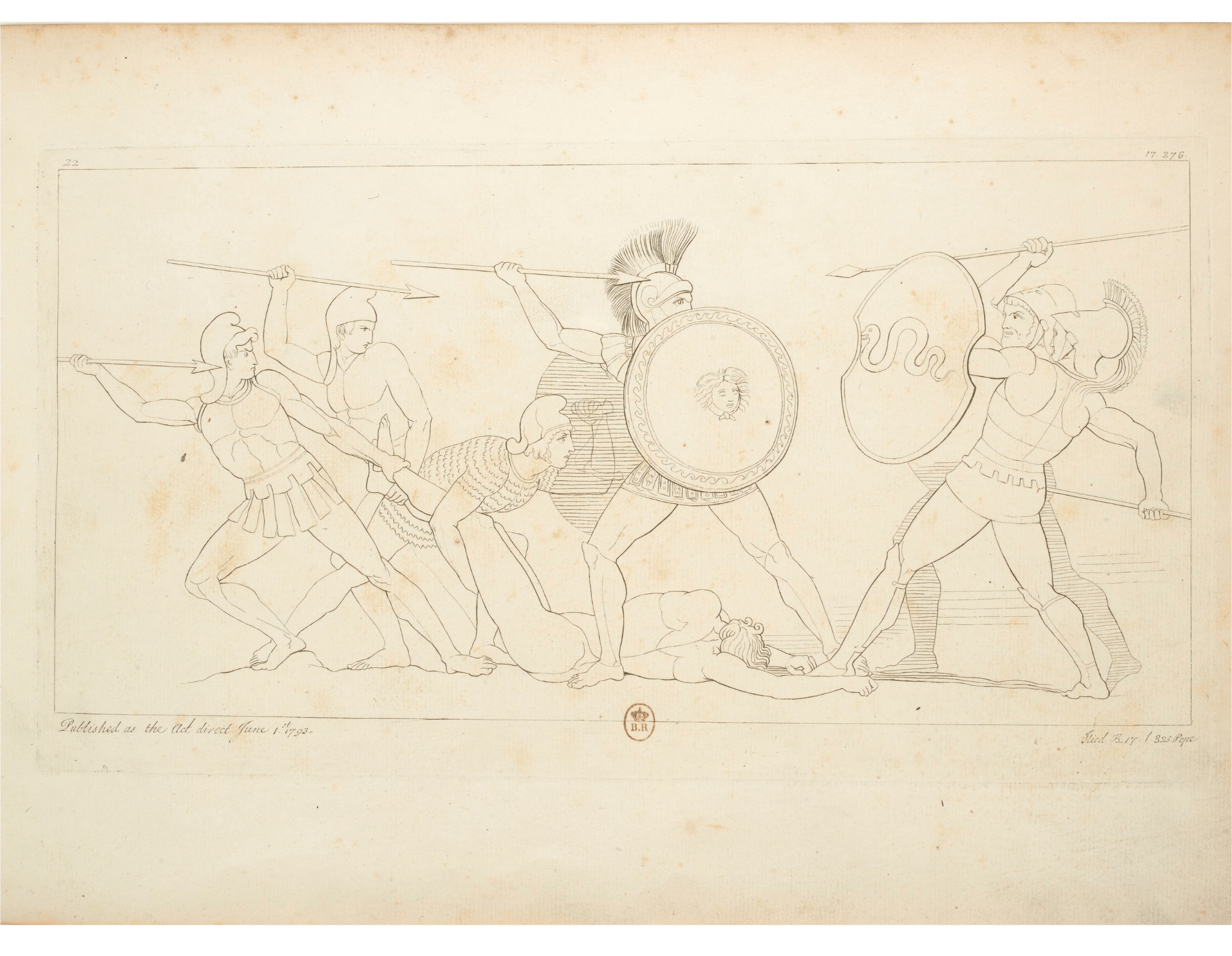

The world that Homer depicts is perhaps less polished than the means that the poet has at his disposal to tell stories. Any account of the Iliad should make clear that this epic is the product, not of an old or exhausted society, but of a fresh, vigorous, new one that celebrates youth, strength, and beauty so fiercely that modern readers often find the Homeric world shockingly cruel—and indeed primitive.

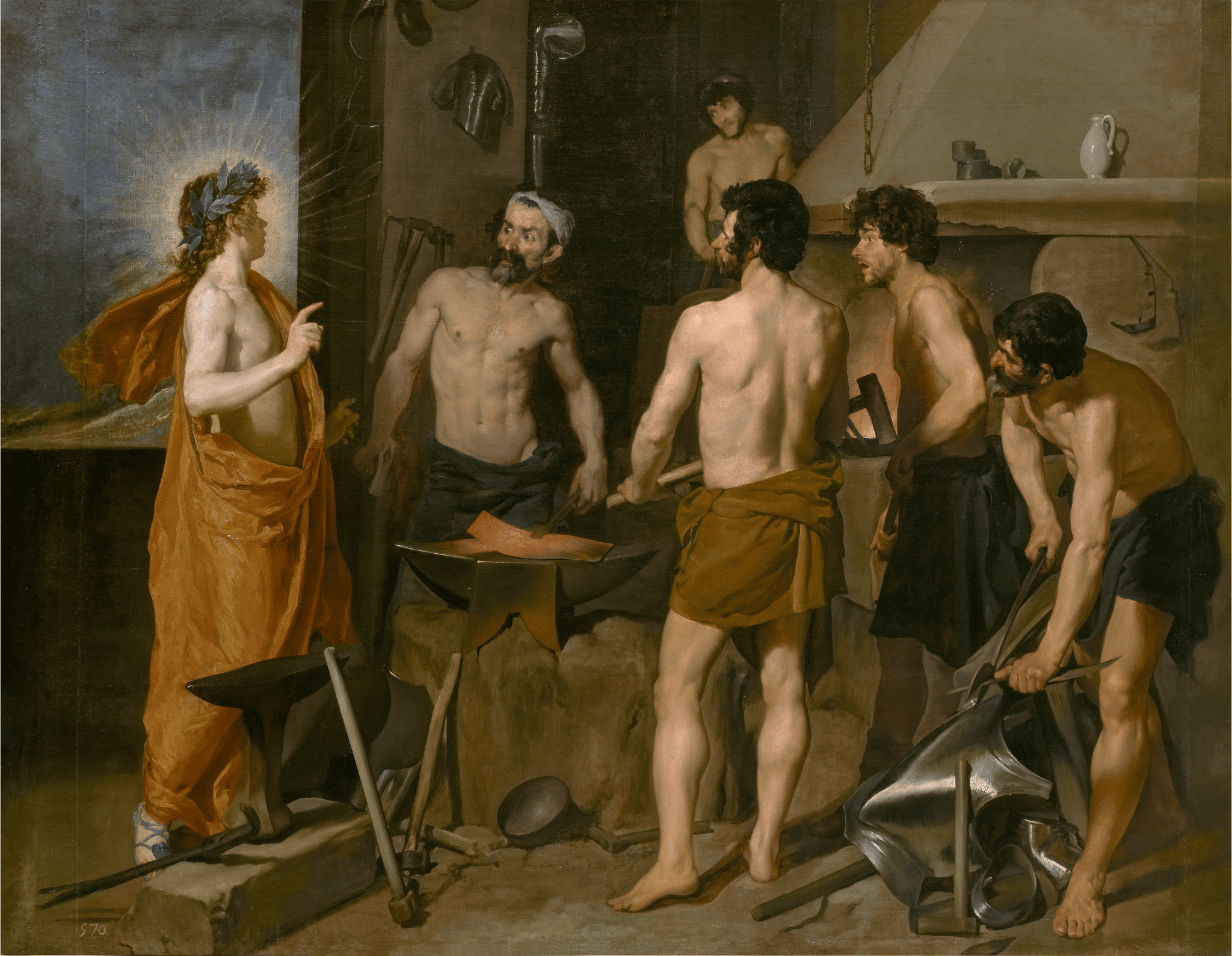

At the end of the first book of the Iliad, the blacksmith god Hephaestus tries to calm a tense situation among the gods on Mount Olympus by reminding his mother about the time Zeus, the King of Gods, grabbed him by the ankle and threw him out of Heaven. After falling for a day, he landed on the island of Lemnos at sunset and ended up permanently lame. When he tries to serve a peacemaking drink to the assembled gods, they laugh at how he hobbles. This diffuses the tension. In the eyes of many classicists today, the scene demonstrates a kind of infantile savagery—the gods behave here like children who rip the wings off insects for fun.

The second book of the Iliad features a scene that seems even harsher, because it involves mortal men rather than gods. One of the few non-aristocratic soldiers in the poem is an ugly, lame, bandy-legged, loud-mouthed commoner named Thersites. His commanders loathe him. He harangues King Agamemnon, leader of the Greek invasion force, in the following words (in Duban’s translation):

Fault-finding Atreïdēs, what, pray, is your beef?

Your tents with bronze abound, and many the woman

Awarded you whenever we Argives raze a town

Are you desperate for gold, that some horse-taming

Trojan might fetch you from Troy, a son’s ransom, whom

I or another Danaan deliver bound,

Or for some winsome girl to gratify your groin,

Whom you cravenly fondle and maul? How grievous

When Argive leaders heap toil on the Argive host!

For pity! Reproaches all, Achaean women,

No longer men! But here let’s do abandon him,

Prognosticating on his gains, that he perceive

Whether we promote his enterprise or not who

Has thus dishonoured Achilles, a better man

By far than he, having pilfered and impounded

His prize. But truly is Achilles unperturbed,

Uncaring quite, or this your final insult were.

Thersites has flagrantly breached protocol by addressing such criticisms of a king to his face. Odysseus, the cleverest of Agamemnon’s officers, responds by clubbing Thersites over the back and shoulders with a golden sceptre, raising a bloody welt. Thersites begins to cry; his fellow-soldiers react thus (again, in Duban’s translation):

. . . the men on his account

Though pained, laughed affably, and furtively peering

Addressed their neighbours each: “Lord what wonder betides!

Myriad goods has Odysseus undertaken,

Plans deftly devising and waking men to war,

But best of blessings on the Argives now bestows

Who bridles this blundering lout, unbearable.

Certain will testy Thersitēs never again

Be predisposed to clash disdainfully with kings.

In the Iliad, death is simply impossible to ignore, whilst wasted human life seems a commonplace reality. Everyone shrugs their shoulders at these things, because they have no choice but to accept it. Thersites tries to complain about all of this and is beaten and laughed at for doing so. Modern readers often sympathise with him rather than with those who scorn him and are taken aback to see him punished for speaking his mind.

To translate the Iliad into a modern language involves finding a means of communicating, not just individual words, phrases, or thoughts, but an entire vision of reality that seems utterly alien. Yet, Homer’s depictions of human nature seem recognisably true, and universal. He is at once sympathetic and utterly pitiless. This pitilessness must be what makes him seem so primitive in a Christian or post-Christian world. We are uncomfortable with a tragic vision of reality.

Do We Need Another Iliad?

As I noted above, it seems fair to ask why anyone would choose to translate the Iliad when so many renditions already exist, some of which have become classics in their own right. Perhaps the most frequently read version is the old Loeb Classical Library edition, which is a godsend to fledging classicists who have not yet mastered the peculiarities of Homeric syntax, grammar, and vocabulary. Among more recent renditions for students, the very best introduction to Homer is Simon Pulleyn’s exemplary edition of Book 1, published by Oxford University Press in 2000. George Steiner’s splendid 1996 Penguin anthology Homer in English provides some idea of the sheer range of English-language literary versions of the Iliad and Odyssey available. Arguably the finest modern verse renditions of Homer are by the late Peter Green, who published the Iliad in 2015, the Odyssey in 2018, and died in 2024 a few months short of his hundredth birthday. Green was a distinguished translator and man of letters and wrote Alexander of Macedon (1970), one of the best-known historical biographies of modern times. His renditions of Homer are the work of an old-fashioned English adventurer. Duban’s translation, much of which was drafted during the pandemic, is the product of a very different moment in history:

The work’s conclusion in 2023–2024 amid the Israel–Hamas War bore witness throughout the world to harrowing on-campus displays of anti-Semitism, anti-Americanism and the assault on American values. Yet in every rendered line I felt the world, like the Iliad itself, reconstituted and preserved. Such was my “personally taken” response to the dissolution from which this Iliad emerged––a work, like its original, seeking the fixity and order of art, even as all crumbled around me. This is what art does, as they who most value it know.

The project’s political dimension is made explicit in the introduction:

This work ... stands as a reproach to Cancel Culture, the movement as of early 2020, gaining apace under the hashtag #DisruptTexts, tweeting its successes as they accrue. “Very proud to say that we got the Odyssey removed from the curriculum this year,” tweets a Lawrence High School English teacher—this in response to a tweet from her friend and colleague: “Be like Odysseus and embrace the long haul to liberation (and then take the Odyssey out of your curriculum because it’s trash).” Lawrence High School (as this Boston boy has known) is one of the traditionally poorest-performing schools in Massachusetts. It is thus, unsurprisingly, pleased to jettison the ballast that would steady it. In the longer picture, its actions are the trickledown of a now decades-long curricular decline in colleges and universities, where courses of a once-recognised formational value are swept aside by the outpour of identity and oppression faddism. “Who kills Homer?” indeed.

Duban came of age in a very different America. He was educated at the Boston Latin School, studied Classics at Brown University, earned a doctorate at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, and left academia to work as a lawyer, but never lost his fascination with ancient literature. His translation of the Iliad serves in many ways as a memorial to the now-vanished ‘middlebrow’ culture of twentieth-century America. Intellectuals have long scoffed at the idea of middlebrow culture, which arose from attempts to make high culture accessible to everybody, regardless of background or social status. Yet there is surely something healthy about a culture that inculcates some notion of self-improvement, as opposed to one that rewards self-pity, self-loathing, and unjustified self-forgiveness.

Duban might be a product of twentieth-century literary culture, but he is emphatically not a Modernist: as he says in his introduction to Homer’s Iliad:

A reproach to characteristically sparse (i.e. excessively monosyllabic) and often unimaginative (or too imaginative) modern, Modernist or post-modern idiom, the present translation seeks to recall and find a place in the estimable literary past.

In line with this approach, Duban’s diction and idiom

are designed to elevate the language of Homeric translation from the banalities of the past seventy years and more… “Banality” includes flatness of expression, most often marked by excessive monosyllabism. It results from lack of effort, imagination, and often the Greek language itself in those who purport to translate. Excessive monosyllabism has also been the fate of recent translations of Homer’s Odyssey and Vergil’s Aeneid.

He makes no apology for his style—quite the contrary:

when translators ‘contemporise’ with anachronistic daring or idiosyncrasy—[Christopher] Logue’s Iliad, [Maria Dahvana] Headley’s Beowulf—they are deemed devilishly clever. The critics, intent on displaying their own flamboyance, parse and parade the peculiarities for all to gawk at. The difference in response reflects Modernist preference: out with the old, however appropriate; in with the new, however outrageous. Il faut épater le bourgeois—today as during the birth of Modernism in the early twentieth century. A 2020 review of [Duban’s book] The Lesbian Lyre concludes that “Duban’s insistence upon discipline, decorum and formality in poetry is part of his philosophy of life.” It would need be, as such notions are nowadays deemed quaint, regressive, or simply obsolete. But let that be. I have sought to create a work “old enough to be new”—new by virtue of its datedness. Indeed, something of what is now considered dated need be preserved, as older, yet serviceable, uses succumb to the social media juggernaut. The rule is time-honoured: when something is replaced, it is all too often lost—if not recollected with scorn.

Duban errs on the side of generosity, not just in explaining and justifying his decisions, but in supplying the reader with appendices, indexes, maps, lists of names, summaries of all twenty-four books of the Iliad, and commentary that is often amusingly pugnacious. He has also created a website for his translation that includes additional supplements that he decided not to include in the printed edition of the book, which weighs in at 621 pages, not including over forty pages of prefatory material. “These fragments I have shored against my ruins,” as T.S. Eliot says in The Waste Land. Duban is trying to ensure the survival of everything he has learned, it seems.

“What Has He Done?”

As Ralph Waldo Emerson, Duban’s fellow-alumnus of the Boston Latin School, puts it in his essay “Spiritual Laws” (1841):

“What has he done?” is the divine question which searches men, and transpierces every false reputation. A fop may sit in any chair of the world nor be distinguished for his hour from Homer and Washington; but there need never be any doubt concerning the respective ability of human beings. Pretension may sit still, but cannot act. Pretension never feigned an act of real greatness. Pretension never wrote an Iliad, nor drove back Xerxes, nor christianized the world, nor abolished slavery.

Duban, with his forthright, studiously unpretentious manner, is steeped in a peculiarly Bostonian culture of learning. The qualities of his Iliad translation are difficult to demonstrate succinctly. This is in part because he has created a kind of performance text that is meant to be read out loud, or recited from memory, so that the insistent rhythm of the verse appears to drive the narrative forward. To read Duban’s Iliad silently on the page is to miss this essential element of what he has tried to create. He is perhaps at his best when rendering Homeric speeches into English. In such passages his innate sense of drama shines through and counterbalances the occasional clumsiness of his idiosyncratic diction.

Readers who have never studied the ancient languages may be surprised to learn that Duban’s translation is often freewheeling. He does not seek word-for-word fidelity to Homer’s verses; rather, he seeks to recreate something of the effect that the original words have on him. The following passage comes from the beginning of the eighth book of the Iliad (in Augustus Taber Murray’s somewhat eccentric translation from the 1924 Loeb Classical Library edition):

[1] Now Dawn the saffron-robed was spreading over the face of all the earth, and Zeus that hurleth the thunderbolt made a gathering of the gods upon the topmost peak of many-ridged Olympus, and himself addressed their gathering; and all the gods gave ear: [5] Hearken unto me, all ye gods and goddesses, that I may speak what the heart in my breast biddeth me. Let not any goddess nor yet any god essay this thing, to thwart my word, but do ye all alike assent thereto, that with all speed I may bring these deeds to pass. [10] Whomsoever I shall mark minded apart from the gods to go and bear aid either to Trojans or Danaans, smitten in no seemly wise shall he come back to Olympus, or I shall take and hurl him into murky Tartarus, [15] far, far away, where is the deepest gulf beneath the earth, the gates whereof are of iron and the threshold of bronze, as far beneath Hades as heaven is above earth: then shall ye know how far the mightiest am I of all gods. Nay, come, make trial, ye gods, that ye all may know. Make ye fast from heaven a chain of gold, [20] and lay ye hold thereof, all ye gods and all goddesses; yet could ye not drag to earth from out of heaven Zeus the counsellor most high, not though ye laboured sore. But whenso I were minded to draw of a ready heart, then with earth itself should I draw you and with sea withal; [25] and the rope should I thereafter bind about a peak of Olympus and all those things should hang in space. By so much am I above gods and above men. So spake he, and they all became hushed in silence, marvelling at his words; for full masterfully did he address their gathering.

This is difficult to read for anyone who is not used to this peculiar pseudo-Biblical idiom. Yet the translator sticks quite close to the original text and scrupulously avoids adding anything of his own (other than the self-consciously archaic style). Compare this to Duban’s rendition of the same passage, which is even more archaic:

O’erspread the dawn her saffron robe around the world,

And lord Zeus Cronídēs in thunder delighting

Convened the throng of Olympian gods immortal,

Cloud-resident on craggy-crested Olympus.

Exhorted he the gath’ring, and the gods gave ear:

“Hearken unto me, you gods and goddesses all,

That I speak what the spirit within me commands.

Let not any goddess nor any god, for that,

Attempt to contravene my word, but assent you

Alike thereto, that I straightaway accomplish

My purpose: whomever I distinguish ranging

Wayward from the gods to hearten either Trojans

Or Danaans, dearly and deservedly drubbed

Shall he return Olympus-bound; or captured hurled

Headlong to hateful Tartarus, remotest off,

Its portals iron pounded wrought, its threshold bronze,

Where gapes neath earth the pit profound, hewn as distant

Neath Hades as starrèd heaven o’erheightens earth.

Then shall you acknowledge me of gods mightiest

E’ermore. But approach and assay me now, you gods,

And ascertain: from heaven sling a golden cord

And tautly gripping it, you heaven-dwellers all,

You would not dislodge me earthward from Olympus

However much endeavouring to dethrone me;

But were I with gladdened heart to attempt the same,

Then would you all midst earth and oceans be deposed,

And the rope next secured about a pinnacle

Of snowbound Olympus, that you all pendant be.

So much superior to men and gods am I.”

Thus he spoke, and utterly silenced they remained,

Astonished at his words, for imperiously

Had he admonished their ranks.

Any reader who treats Duban’s verses as prose, without paying attention to the rhythm, will find all of the curious word order (“in thunder delighting,” “Its portals iron pounded wrought,” “utterly silenced they remained”) simply perverse. Then there is the diction.

Phrases like “cloud-resident on craggy-crested Olympus” and “dearly and deservedly drubbed” are embellished for effect; they don’t obviously reflect Homer’s own words. Also, they feature alliteration that vaguely recalls the conventions of Old English verse, rather than those of Greek or Latin epic. In line 2, Duban refers to Zeus as “Cronides” (‘the son of Cronos’). This isn’t in the original text. Evidently he is trying to add a further layer of archaism to the Iliad, and for some tastes this may seem gratuitous. But Duban has a sweet tooth for this sort of grandeur.

In the first line in this passage, Homer describes dawn as “yellow-robed” or “saffron-robed,” and says she herself is spread all over the earth. Duban changes this slightly so that dawn spreads her saffron robe over the earth. There are other such changes throughout Homer’s Iliad in a Classical Translation that might lead some readers to question how closely Duban has read Homer’s Greek. That would be foolish: Duban holds a doctorate in Classics from Johns Hopkins and has been thinking about ancient epic for well over half a century. Even so, it wouldn’t be difficult to go through his translation line by line to show how he has consistently altered the text. But that would miss the point of the exercise.

This translation is a faithful attempt to replicate the Iliad as it sounds inside Duban’s head. For all its scholarly apparatus, this is a deeply personal project. Readers who persist all the way to the end will come to feel that they know Jeffrey Duban at least as well as they do Homer or his Iliad. He has put his whole self into the introduction and commentary as well as the verse, and the depth of emotion throughout seems palpable.

Why did Duban undertake this exercise, if he was not trying to produce a faithful rendition of Homer’s Greek? The main epigraph to this volume, a quotation from Marcel Proust, provides a few clues as to why Duban chose to work in such an elaborately archaic style. There is more to all of this than mere nostalgia, or antiquarian interest.

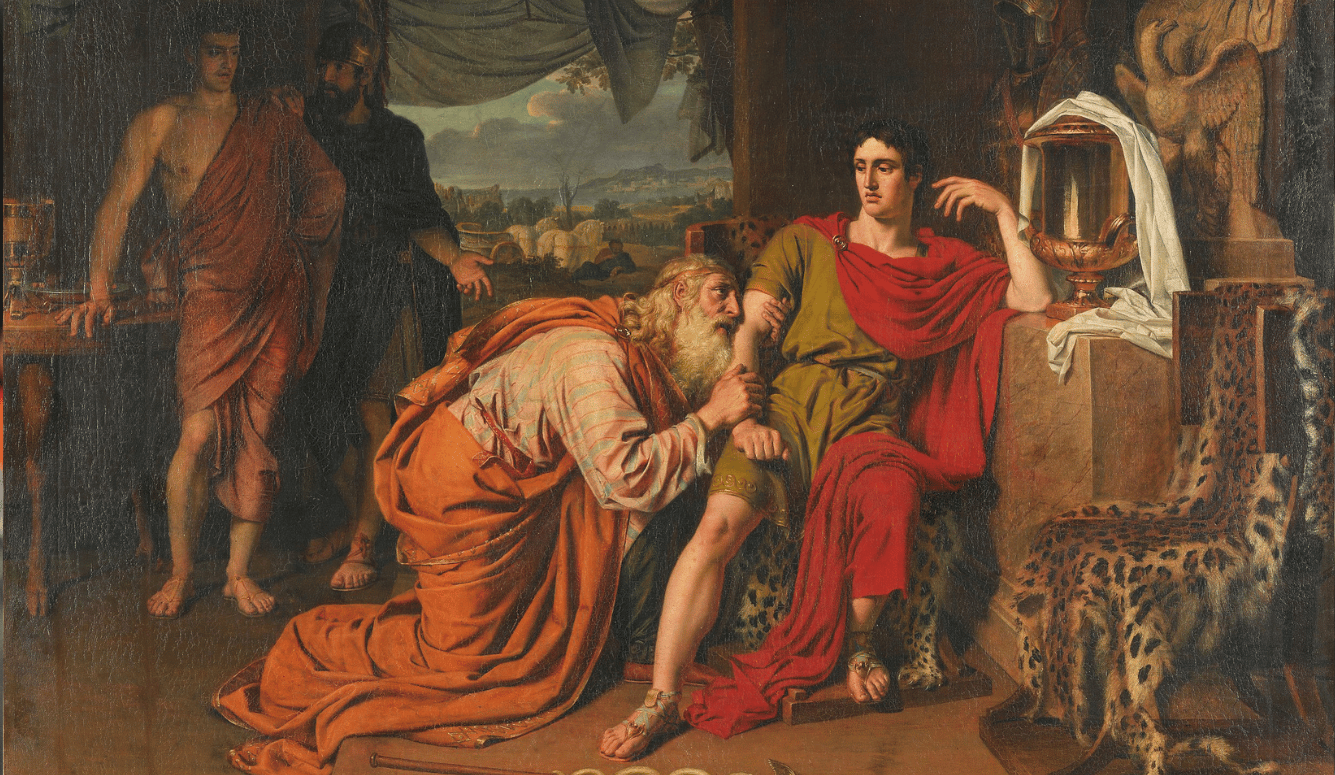

Attentive readers will note that the translation is dedicated to the memory of Paul Petrek-Duban (1989–2019), whom Duban describes as “my son, my hero, and best boy.” In other words, Homer’s Iliad in a Classical Translation was Duban’s way of working through grief. The Iliad is not just a poem about war or the wrath of Achilles. In the twenty-fourth and final book of the epic, Priam, the aged king of Troy, visits the tent of the Greek hero Achilles to ransom the body of his son Hector, whom Achilles killed in single combat. Achilles says to Priam, in Duban’s translation:

… you were once reported

To rule, in offspring and fortune felicitous.

But, from the time the immortal gods rained sorrow

On your being, unending war and butchery

Afflict the town. But abide, nor unabated

Be the heartbreak for your son; nor will you restore

Him, enduring some other misfortune ere then.

To read this passage is to understand at last why Duban embarked on this project. It is not an attempt to seek literary glory, professional recognition, or a political triumph in the culture wars: it is a memorial to his son. No child could wish for a more moving tribute.