Cancel Culture

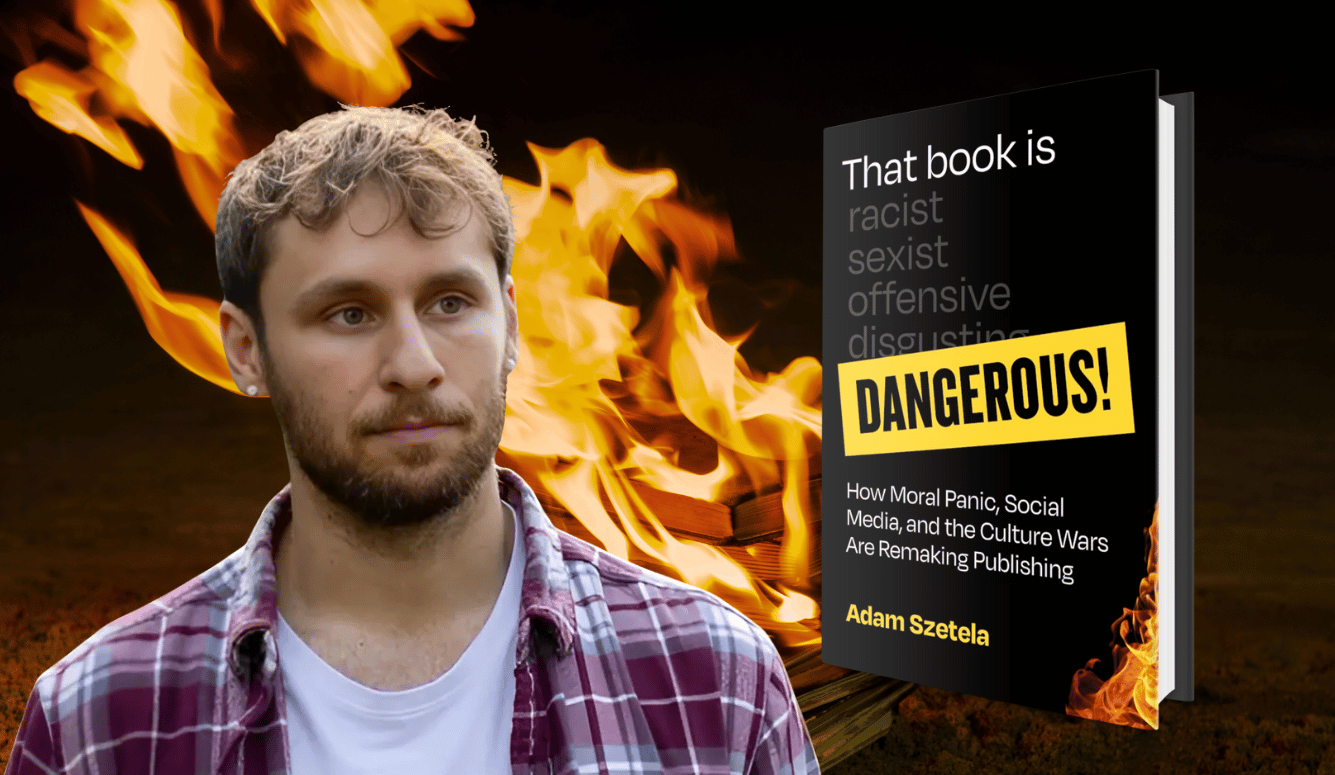

How Cancel Culture and Sensitivity Readers Are Shaping the Publishing Industry and Silencing Dissent | Quillette Cetera Ep. 51

As literary gatekeeping intensifies in the age of social media, author and Harvard fellow Adam Szetela joins Zoe to unpack how moral panics, elite ideology, and institutional cowardice are transforming publishing—and why the culture wars are being fought sentence by sentence.

In this episode of Quillette Cetera, Zoe Booth speaks with Harvard fellow and Cornell PhD Adam Szetela—author of new book That Book Is Dangerous: How Moral Panic, Social Media, and the Culture Wars Are Remaking Publishing (MIT Press, 2025).

A working-class kid turned literary insider, Szetela exposes what he calls “the sensitivity era”: a cultural climate in which books are cancelled before they’re published, authors are shamed into grovelling apologies, and sensitivity readers act as ideological enforcers—surveilling fiction for offence.

Drawing on eye-opening examples and experimental research conducted at Cornell’s Social Dynamics Lab, Szetela explains how peer pressure alone can turn readers against even canonically progressive figures like Allen Ginsberg—a gay, far-left poet celebrated in queer literary anthologies. He also reflects on the publishing industry’s class divide, the fragility of elite institutions, and why pro wrestling and bodybuilding may offer a better education than the Ivy League.

From J.K. Rowling and Goodreads mobs to the politics of soccer and masculinity—this is a frank and timely discussion about literary freedom in an age of moral panic.

Transcript

ZB: Thank you so much for joining me this morning. Your book is great. It’s your first, I believe?

AS: Thanks for having me. Yeah, it’s my first book.

ZB: You should be very proud. It’s a very interesting and timely read, and it’s about a topic not many people are familiar with. Maybe those who work in academia know a bit more, but you talk a lot about sensitivity readers in the publishing industry. What exactly is a sensitivity reader?

AS: So, sensitivity readers—just to give you some context—it’s not until 2016 that you actually see that phrase on X, or Twitter as it was then. I think they’d existed in some form before, but it’s around then that the role becomes codified as a profession.

A sensitivity reader, in short, is someone brought in to read a manuscript not for traditional editorial concerns, but for moral concerns. And in today’s climate, they’re not evaluating whether a book might be offensive to, say, Christians. It’s about whether it could be potentially offensive to African Americans, trans readers, or other marginalised groups.

A core feature is that the sensitivity reader must share an identity with the fictional character. So, you can be a black sensitivity reader reviewing a novel with black characters, or a trans sensitivity reader looking at a non-fiction book about trans people. That’s really the only requirement. You don’t go to school to become a sensitivity reader, you don’t get an MFA to do it.

It’s like: I’m Adam, I’m half Asian American, and I’m offering sensitivity reading for half Asian American characters. The identities get quite granular. I’ve literally seen listings like: “I’m a quarter Filipino and queer—that’s what I’m reading for.”

ZB: Yes, you mention one publisher that has a coalition of readers who consult authors on issues as different as African American culture, fatness, familial homophobia, conception via sperm donation, rural queer experience, Chinese American culture, furry fandom, interracial relationships, contemporary Jewish culture, mental abuse by a parent, travelling while black, Hinduism, ableist physician experiences, Iroquois culture, men who survive rape, LGBTQIA2+ representation, and witchcraft. They’re really covering all bases there.

AS: Yeah, it’s like any market—once there’s an initial push, it just expands. All of this really started with race, followed by sexuality. And now we’re bringing on witches to read books for the seven people who identify as witches.

ZB: Incredible. I wonder if they have a union—the Witchcraft Union. Actually, speaking of witchcraft, there’s a very interesting example you include—you list a slew of the worst excesses of cancel culture in publishing, but one stood out…

AS: I think I know what you’re talking about. A sensitivity reader posted on X in response to Rowling’s supposedly transphobic comments—something to the effect of: someone in the UK needs to find her and break her nose until blood gushes out. This, from someone whose job is to be “sensitive.”

ZB: Yes. They publicly demanded that Rowling be jumped—wishing her nose would break and her teeth be knocked out. Sounds like something you’re more experienced with in your UFC days. But does this not show—not just irony, but the hypocrisy—of people who make a living being “sensitive,” who purport to be beacons of progressivism, yet they’re literally calling for violence online against people who oppose their orthodoxies? It’s shocking.

AS: Yeah, as you point out, it’s plainly hypocritical. But I also find it really interesting from a sociological, even psychological, perspective. So, in my book, I use a term I coined: militant fragility. It occupies this interesting contradiction.

On the one hand, these are the most fragile, sensitive people on the planet—if they’re actually being genuine in their taking offence. I think some of them aren’t. But let’s assume they are: someone is so shattered by whatever Rowling tweeted that week. But on the other hand, they adopt this very militant posture—it’s aggressive, confrontational. You’ll have a young woman, or a young non-binary person, saying, “Let’s jump J.K. Rowling.”

You see this on college campuses too. Watch the video of students surrounding Nicholas Christakis at Yale, or at Evergreen State when they went after Bret Weinstein. These eighteen-year-old kids—some of them are genuinely crying over the suggestion that you should be allowed to wear whatever Halloween costume you want. But at the same time, they’re in his face, yelling, and you’re watching thinking: is this about to become a physical fight?

And both in publishing and in places like Yale or Evergreen, we’re talking about largely upper-class kids. Just as the only people who can afford to be an assistant editor at Penguin Random House in Manhattan for $51,000 a year are upper-class kids. These are people who didn’t grow up with actual violence. Because I can tell you: if you walked into any of the neighbourhoods I grew up in—or have lived in throughout my life—and got in a grown man’s face and told him to shut his mouth, like they did to Christakis, you’d get your arse whooped immediately.

ZB: You’re from Kansas, is that right?

AS: No, I’ve spent most of my life in and around Boston. I did live in Kansas for a few years, though.

AS: And there’s a lot of sociological research about how wealthy people raise their kids. They’re raised not to occupy a place in the world, but to take their place. These are the people who ask me for extensions at Cornell. These are the people who send food back if it’s not exactly right. These are the kids who get in a professor’s face and tell him to shut up—because they’ve never been punched in the face. That’s not what happens when you grow up in Greenwich, Connecticut.

ZB: Yes. I actually just tweeted an excerpt from your book this morning that really resonated with me. I think it’s the last sentence of your acknowledgements. I never read acknowledgements, but I did in your case.

AS: I wanted to write a good one—because no one reads them! I thought, this needs to be worth reading. So I just went for it and had fun with it.

ZB: You’ve taught me my lesson—I might start reading them more. Yours were really interesting. You end with a quote from Karl Marx. At first, I thought, “Where is this going?” But it says: “Men make their own history, but they do not make it just as they please; they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves, but under circumstances directly encountered, given and transmitted from the past.” And then you write that you’re thankful the circumstances of your upbringing weren’t the same as those of the elites you discuss in the book.

That really resonated with me. I come from a big country town—a regional town in Australia. Funnily enough, I was one of the more posh kids there, because my dad went to university and I spoke in a way that people commented on—like, “Why do you speak like that? You think you’re better than us.” But since moving to Sydney, especially to a more affluent area, I’ve seen the discrepancy between kids who grew up with parents who were criminals, in jail, or dead from addiction—and kids who’ve been coddled their whole lives.

AS: For sure. And I think people like yourself, people like Rob Henderson, people like Musa al-Gharbi—who went to community college before going to Columbia—those people tend to produce some of the most interesting academic work, at least among those who choose to stay in academia.

Musa did a PhD at Columbia. Rob did his PhD at Oxford. But they come from non-traditional backgrounds compared to the typical person getting a PhD at Oxford or Yale. So it makes sense why their work is compelling. They’ve got the academic tools and sharp minds, but also real-world experience that your average Ivy League professor doesn’t have.

I’m talking about someone who grew up in Greenwich Village, did their undergrad at Amherst, then got a PhD at Yale, and now teaches at Harvard—never having worked a job outside of campus. And ironically, it’s the Left that obsesses over positionality and epistemology—but usually only in terms of melanin, not whether someone has ever had a wage job.

ZB: Yes. And the review we published of your book yesterday was by Robert Huddleston. I know you’re not big on reading your own reviews…

AS: I haven’t read it yet. I will. He’s a smart guy—I’m curious what he wrote.

ZB: It’s interesting because the review covers both your book and another one: William Deresiewicz’s The Death of the Artist: How Creators Are Struggling to Survive in the Age of Billionaires and Big Tech from 2022. I haven’t read that book, but even though the topics are quite different, the reviewer finds a strong common thread. Both books address the way financial pressures and the online environment are shaping creative industries.

As you discuss in your book, everyone is now a literary critic. And with the collapse of many entry-level jobs, young people feel enormous pressure. They’re more inclined to tear each other down because the opportunities are so limited. And now, with the internet, it’s just so easy to destroy your peers. Goodreads, Twitter, online review sites—it’s all part of that.

It’s an interesting review, and I think you should read it. It definitely ties in with your work.

AS: Yeah, I like Will’s work. I’ve got at least one of his books on my shelf. One of the things I’m really interested in is incentive structures—and also just recurring features of the human condition.

I find it completely ridiculous when people assume basic emotions like jealousy don’t apply in literary culture just because the people involved are left-leaning and ostensibly want to “do good.” But if you look at cancel culture in publishing, a lot of it targets debut authors—especially ones who’ve landed six-figure advances. That’s rare. The vast majority of people who write books will never see that kind of money, even if they get published.

So imagine you’ve written three novels, haven’t even landed an agent, and then you see someone tweeting about their massive book deal with Penguin Random House.

I don’t think you need a sociology PhD from Harvard to recognise that someone who’s infuriated about that probably isn’t going to say, “I’m so angry because my literary career is in the toilet and Amélie Wen Zhao’s isn’t.” It’s reasonable to assume that kind of anger might manifest in a more sublimated way.

And I think that’s at least part—though not the whole—of why certain people get targeted while others don’t.

ZB: One hundred percent. And would you say the Left is more critical of people on the Left? Or do you also see this happening with, say, Mike Pence’s autobiography? They also tried to cancel Jordan Peterson’s book, as you mention. But is it mostly infighting? Or do they go after the Right as well?

AS: Yeah, the common denominator—whether you’re looking at picture books, novels, adult non-fiction, or journalistic outlets—is progressives going after other progressives for allegedly not being progressive enough. That might mean accusations of racism, or transphobia, or some other ideological transgression.

And it makes sense, because when you’re talking about fiction and poetry especially, there’s not exactly a big cohort of right-wing novelists being published by Penguin Random House. Those who do exist are mostly self-publishing through Amazon. So when controversy erupts, it’s almost always left-of-centre people targeting other left-of-centre people for not being left enough.

Now, to your point: yes, there’s been some uproar over Mike Pence’s book and Jordan Peterson’s 12 Rules for Life when it was due to be published by Penguin Random House Canada. In Peterson’s case, there was an internal meltdown that led to a town hall meeting where staff were literally crying about the book being published. And 12 Rules isn’t even a political book—it’s self-help. But because Peterson had made comments about pronouns, it was viewed as an act of violence.

But those are more the exceptions that prove the rule. Because when you’re looking at the places where people want to be published—Penguin Random House, HarperCollins, Simon & Schuster, Hachette, and a few others—these houses are as politically homogeneous as elite universities. And that’s not surprising, since most of their staff come from elite universities. They’re very left-leaning.

They might have one imprint for conservative non-fiction, and you can get published there if you already have a massive platform. So even if people don’t want to publish Mike Pence, they know he’ll generate absurd profits. Same with Peterson.

But if you’re a right-leaning non-fiction writer with no platform, or a right-leaning novelist, it’s going to be hard to get published. Even finding an agent is difficult—because agents need to sell to publishers. And if publishers aren’t interested, you’re out of luck.

Even authors like Chuck Palahniuk and Bret Easton Ellis, who came up in a different era, likely wouldn’t get Fight Club or American Psycho accepted today. That’s just a fact.

ZB: Shocking. One of my favourite books and favourite authors—Bret Easton Ellis. I’ve read so many of his novels. He’s incredible. That’s such a shame. Has he actually said he probably wouldn’t get published today? Or is that your view?

AS: He has, yes. And Chuck Palahniuk has said the same thing.

And American Psycho is such an interesting case. It was one of the few books in the 1990s that generated a backlash comparable to what we see today. The big difference, of course, was that there was no social media then, so it was somewhat contained.

But people went after it—he was dropped by his publisher. The difference between then and now is that he was instantly picked up by another publisher. The book was made into a film. It was just a different climate. There were still people willing to defend a controversial work.

And that book is deeply disturbing—far more than the film. It includes graphic scenes—like one where a woman’s head is sawn off.

ZB: “Don’t just stare at it. Eat it.” That’s my favourite quote—I use it all the time.

AS: “Feed me a stray cat.” “Why are you homeless? You don’t want to work.”

ZB: Shocking. But such a good book. Have you looked into any indie or new publishing houses that have come up in response to all this?

Two pop into my head. One is Passage Press—are you familiar with them?

AS: I’m not, no.

ZB: It was created by a big Twitter personality—one of those anonymous, quasi–alt-right, bodybuilding guys. I believe his name is Lomez. It seems to have had some success.

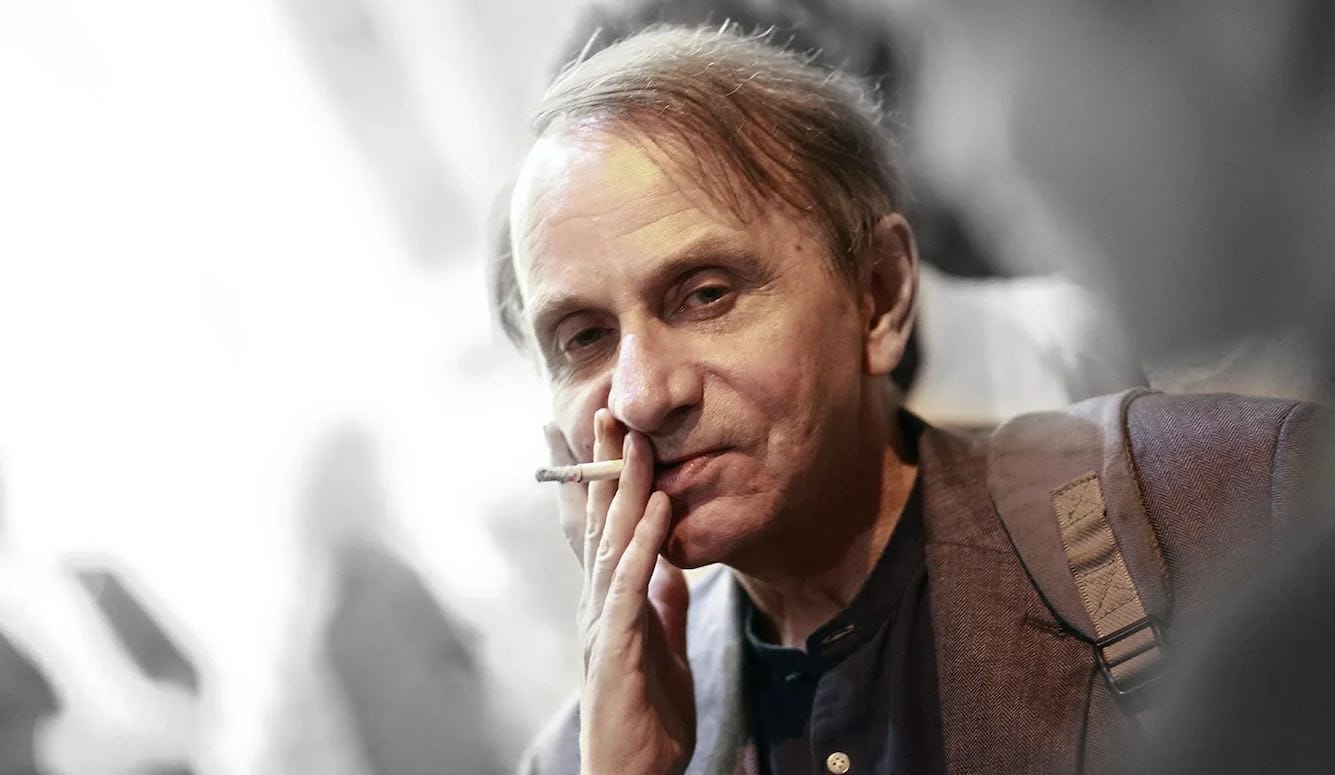

The other is Flammarion, which I think is based in Europe. They publish Michel Houellebecq’s work, and their brand seems to be focused on more heterodox or controversial fiction writers.

But yes, as you’ve said, by and large, the industry is dominated by the big five publishers. It’s pretty much a monopoly.

AS: Yeah. To answer your question more fully—Bernard Schweizer, who I mention in my acknowledgements, started a press specifically in response to all this. It’s a press that won’t discriminate against authors producing controversial work—or, God forbid, a conservative who wants to write fiction.

His press is called Heresy Press. It’s now an imprint of Skyhorse Publishing, which in my opinion is the gold standard when it comes to supporting heterodox voices. They’re genuinely committed to free speech.

They’ve literally published The Case for Palestine and The Case for Israel—so they’re not pushing one ideological line. It’s a rare thing. A sacred space in today’s publishing world.

But yes, it’s unfortunate. There’s a material reality to writing. If you’re trying to make it your career and not just a side hobby, it becomes very clear what kinds of work are valued—and it’s not the next up-and-coming Chuck Palahniuk.

ZB: So, talking more about the social psychology behind these cancellations—and as you’ve said, it’s really hard to make money in the arts—you did some experiments at Cornell’s Social Dynamics Lab.

AS: Sounds sketchy when you put it like that—“experiments.”

ZB: [Laughs] Yes, what kind of experiments? You did some experiments at Cornell’s Social Dynamics Lab, which I found fascinating. What did you study there, and what did you find?

AS: I did my PhD in English at Cornell, but when I was admitted—I don’t know if it’s changed since then—I was promised quite a bit of academic freedom. So, while my graduate coursework was primarily in English, I also studied psychology, sociology, history, and American studies. I was lucky in that way.

But to give you the short version, we wanted to test whether people could be socially influenced to falsely accuse literature of moral transgressions. Basically, we were looking at how powerful group influence can be in these kinds of literary controversies.

So the experiment had two groups. The first group got four poems. Alongside each poem, they were given sixteen descriptors to choose from—some aesthetic, like “well-written” or “poorly written,” and some political, like “progressive,” “conservative,” “racist,” “sexist,” etc. They’d read the poem and pick three descriptors.

Three of the poems had been accused of moral transgressions in real life. One was a poem called How-To, published by The Nation—a very left-wing magazine. It had been accused of racism and ableism. And when you go to the site now, the poem has a censure statement posted above it that’s actually longer than the poem itself. The editors are basically grovelling—saying how sorry they are for publishing something so harmful.

But when we gave it to the first group, around 95 percent of respondents didn’t see anything wrong. No one clicked “racist.” A tiny percentage might have—but that could just be noise. The same went for the other controversial poems. Ordinary people simply didn’t see the problem.

Then, for the second group, we gave them the same poems, but added a short critical statement supposedly from an influential literary critic. I wrote the statements, but they were based on real criticisms. For How-To, it said something like: “This poem is so racist it does real harm to the African American community.”

Then we told participants that at the end of the experiment, they’d be asked to log into their Facebook accounts and take part in a public discussion where they’d have to justify their responses.

So now, there’s some social pressure—not just to conform with the critic, but also to justify yourself publicly.

And what we found was that the number of people who flagged the poems as racist, sexist, etc. just skyrocketed. With only a tiny nudge of pressure, people flipped. And remember, this doesn’t even come close to the real-world pressure people face online—on Twitter or Goodreads—where accusations fly and reputations are at stake.

AS: The most interesting part for me was when we used A Supermarket in California by Allen Ginsberg—a poem that, in the real world, has never been accused of anything. Ginsberg was a far-left poet, he was gay, he’s included in the Columbia Anthology of Gay Literature. He’s as credentialled as it gets.

And the poem is just about shopping in a supermarket. When we gave it to the first group, no one found it problematic. Then for the second group, I wrote a fake critique saying it was homophobic, and attributed it to a respected critic.

And even that worked—about 35 percent of respondents clicked “homophobic.” I was like, wow, we just got people to call Allen Ginsberg—a gay poet—a homophobe. That’s how powerful this is.

So now, think about these real-world controversies—thousands of people piling onto Goodreads and Twitter, calling a book racist or sexist before it’s even released. The question is: how many of those people actually believe the accusations? My research suggests a significant portion are just going along with the crowd.

ZB: Fascinating research. Who participated in the study—were they students?

AS: No. Students are a terrible sample—unless you’re specifically studying college dynamics. They’re cheap, which is why they show up a lot in academic research, but they’re not representative.

We used an online platform to recruit a random sample that roughly approximated national representativeness in terms of race, gender, age, etc.

ZB: So you can’t even say these were just progressive students or university-educated types. That’s terrifying. It’s really terrifying to realise how easily people can be whipped into a frenzy based on a total lie.

AS: For sure. I’ve spent the past ten years surrounded by academics and hyper-progressive people. And in the social sciences, everyone knows the Stanford prison experiment, the Milgram experiments with the electric shocks—all these classic studies about group pressure and authority.

But the way they’re discussed is always like, “Wow, those people back then were so gullible. That couldn’t be us.” There’s this unspoken assumption that we’re smarter—we’re on the left, we’re educated, we’d never fall for that.

But as someone who’s watched this culture closely for years, I think it is us. You can call it a mob, you can call it a moral panic—whatever language you prefer—but I think there’s a strong empirical case that a lot of people in these circles behave in ways that mirror exactly the groupthink and conformity they love to condemn in others.

ZB: Speaking of deadlifting and weightlifting and wrestling—I’m not that into wrestling, but weightlifting I’m very interested in. I’m a keen weightlifter, and it was interesting to read that weightlifting and wrestling have had an impact on your life and the way you see the world. Maybe even on your resilience to this culture of sensitivity. Could you say a bit more about that?

AS: Yeah. I’ll just forewarn people: this might stray into the territory of so-called “toxic masculinity.”

But yeah, growing up—and even now—I’ve always been involved in combat sports. Wrestling was my thing when I was younger—not WWF wrestling, but folk style and Greco-Roman. I also did powerlifting, competed in that, and was very into bodybuilding.

I think there’s a culture in those activities where weakness is not valorised—it’s something you’re supposed to address, overcome, and build resilience from. I don’t think it’s hyperbolic when someone like Lex Fridman says he’s learned more on the jiu-jitsu mat than at MIT. He’s not talking about academic skills—he’s talking about mindset. And I think that mindset is one the people I write about in my book often don’t have.

Here’s a little anecdote. I was invited to a soccer match last summer. I’d never been to one before. Frankly, soccer doesn’t interest me—there’s not enough content. But I went.

I was in the stands, relatively bored. One player got tripped and fell down, screaming in pain, rolling around on the ground. The match was still going, and I was watching him thinking: this guy must’ve torn his ACL or something.

But then the game continued, and he realised the ref wasn’t going to stop play or call a foul—and suddenly, he just stood up and jogged off. It was all feigned outrage.

And to me, it seemed very similar to what I studied with Twitter pile-ons over literature. There’s this massive performative disjunction between what’s actually happening and how the person is presenting it.

It reminded me of what Bradley Campbell and Jason Manning call “victimhood culture,” as opposed to traditional honour cultures. In UFC, for example, a guy might enter round five with a broken nose or a broken hand—and you wouldn’t even notice. It’s the opposite of performative fragility. It’s: broken nose? Doesn’t matter. I’m not showing it. It’s not cool to signal weakness.

Whereas in soccer, apparently, it is. Maybe that’s another book—the connection between professional soccer and the kind of people who sit at their laptops all day feigning outrage.

ZB: It’s a fascinating similarity. I think my childhood as a competitive ballet dancer—with very strict teachers—really drilled into me the idea that victimhood is not an option.

AS: That sounds very Black Swan.

ZB: Yeah, something like that.

Before we move on, I wanted to circle back to what you said about your social experiments—and how easy it is to spread what might be a complete lie about someone and their work, based purely on a subjective interpretation, whether genuine or not.

Have you seen, in your research for the book, an example where the consequences were especially devastating for someone?

AS: Yes. There are a few different ways to answer that—because sometimes the accusations are so absurd they’re fascinating in themselves. But in terms of actual personal consequences, one example stands out.

There was an author named Jessica Cluess. At the time this happened, I believe she’d published three or four books, which had done reasonably well.

So there was a woman involved with this organisation called Disrupt Texts—a progressive group trying to get its ideology into schools and publishing houses. “Disrupting” a text means pointing out the racism or sexism in it. So there are teachers who say, “I’m forced to teach Shakespeare because it’s on the curriculum, but I disrupt it by getting the students to look for misogyny in the text.”

It’s a very reductive way of teaching literature—reminds me of Soviet-style pedagogy.

Anyway, someone involved in Disrupt Texts tweeted something like: “Everything published before 1950 is racist and we shouldn’t be teaching it.” And people in her circle applauded it.

Jessica Cluess responded, and not politely. She basically said, “That’s really stupid.” She pointed out that it was an ignorant statement—asked if the person had ever read anything from the Harlem Renaissance, etc.

And the mob turned on her. They called her racist, they began tweeting at her publisher and her agent. She lost her agent. And, if I remember correctly, she had a book under contract—part of a series—and after that, she basically disappeared from the scene.

She did issue an apology, which read like it had been written under duress—like she had a knife to her throat. It was bizarre.

AS: And the mob wasn’t satisfied with the apology. They took screenshots and even marked it up with red ink—literally edited it like teachers correcting a student’s essay. They crossed out her words and replaced them with more “morally appropriate” ones.

Then her agent got involved. He issued a tweet that didn’t satisfy the crowd, so he issued another one. And in the end, he tweeted publicly that he was severing ties with her—saying something like, “This is no way for a white woman to speak to a Dominican woman.”

Race had nothing to do with the original exchange.

And I’m sitting there thinking: this is a grown man. This is someone who should have his author’s back. And instead, he’s spinelessly trying to save his own reputation by throwing her under the bus.

I don’t know Jessica personally, but she may have had kids. That book contract was probably helping to pay a mortgage. These are real-life consequences.

All for pushing back on a statement that was objectively ridiculous.

ZB: There are some very spineless people out there. And I actually believe that, due to evolutionary pressures or whatever it might be, the majority of people are spineless. Maybe we’re the weirdos—those of us who can’t stand the injustice of it all—who would’ve been ostracised from the tribe for sticking our necks out and probably murdered. But yes, it’s scary.

AS: To tie this back to your interest in bodybuilding—if I can stretch the analogy that far—when I see a grown man like her agent just squeamishly apologise and throw his own author under the bus, part of me thinks: this guy needs to get his blood work done. Check his hormone levels.

Can you engage in that kind of behaviour if you have healthy testosterone levels? I’m not sure. I haven’t done the research. But at a certain point, it starts to feel physiological. Maybe there’s something hormonally wrong—just no basic fortitude. No proverbial spine.

ZB: That’s a very good question. And I think there are a lot of aspects to this. Even this conversation has made me think more about the feminisation of certain industries. It used to sound like a conspiracy theory to me—until we published a really long and fascinating essay on it, about how sex ratios in academia inevitably influence the way the field operates.

And how do women affect it? Well, women behave differently to men in many ways. Our violence is often reputational, not physical. We’re unlikely to physically attack another woman—but we’ll absolutely destroy her reputation, especially now that we have social media.

I don’t know the stats, but I would guess there are more women than men in publishing—and particularly in fiction, since I believe women buy more fiction than men. Is that correct?

AS: That’s correct. And I’d say the typical person working in American publishing—especially in the mainstream big five—is a middle- to upper-class white woman living in Manhattan.

ZB: So that inevitably affects the behavioural norms in the industry. It’s no surprise, then, that publishing has a particularly bad problem with cancel culture.

Did you get into the gender aspect in your book? I don’t recall that being a major theme.

AS: No, I didn’t. But it’s something I’d like to write about at some point.

Here’s the thing: leftists often make arguments about proportional representation—e.g., “There were X number of books about black characters this year, but that’s still less than their percentage of the population.” The same with trans characters, queer characters, etc.

But the most glaring demographic skew in publishing is gender. The industry is overwhelmingly female. And I don’t think it’s unreasonable to ask whether that might help explain why so many young men—especially in primary and secondary school—don’t like reading.

They don’t connect with the books they’re assigned. A book like Fight Club, for instance, wouldn’t be published today by a first-time author. And I don’t think that’s incidental.

When I was growing up, I didn’t particularly like reading. I recently got a DM from a mother of three who had watched my interview with Coleman [Hughes]. She said all three of her sons hate reading—partly because they’re only assigned books with female protagonists who are constantly complaining about men and masculinity.

If you look at what young men are watching on YouTube—the content that trends algorithmically—and then try to find a fictional equivalent, it just doesn’t exist.

And if I were to write a book for those young men—say, something about UFC culture or masculinity—I’d still have to consider a second audience: the upper-class white woman living in New York City. Because she’s the one who has the power to get it published.

If you go to Manuscript Wishlist or other agent databases, it becomes clear that both publishers and agents are overwhelmingly women. And they often want books that reflect their own interests. Those interests don’t typically include combat sports or other masculine pursuits.

ZB: Fascinating. Maybe there’s an opportunity for more books to be written about that. But of course, they wouldn’t be published by traditional houses. They’re being written—but they’re just self-published on Amazon.

AS: Exactly. I don’t really read self-published books very often. Most of my reading is academic non-fiction. But I have friends who read far more fiction than I do—and some of them are also trying to get novels published. And they say: if you want something edgy or traditionally masculine, you have to go digging through Amazon’s self-published titles.

ZB: I used to love Haruki Murakami—although my ex-boyfriend hated his books. He thought the depiction of men was completely unrealistic. He’d say it was all a fantasy: the protagonist could just have sex with any woman he wanted, and women would appear out of nowhere and seduce him.

But I did enjoy his work. And Michel Houellebecq too—the French author. His male protagonists are very toxically masculine. But again, he’s not widely read in the Anglosphere, and in France, he’s extremely polemical. I suspect people with good taste like him—but maybe in broader pop culture, he’s less respected?

AS: Yeah. It’s unfortunate. Thousands of books are published every year—and yet, the fact that we can run out of relevant names after thirty seconds… And a few of those names are guys in their fifties who first got published in 1994… that’s not great.

ZB: Not a good sign.

Well, we’ve been going for almost an hour. Is there anything else you’d like to talk about?

AS: Cats?

ZB: Cats are great. You’d love Haruki Murakami—he talks about cats all the time. He’s obsessed.

AS: Okay. I’ll keep that in mind. I’m a big dog guy, too. I don’t judge.

Do I have anything else to add? No, not really. I mean, at this point, it’s hard for me to read any book about cancel culture or wokeness and find something new. I think Musa al-Gharbi’s book from last autumn was very good.

But most of this territory feels stripped bare.

What I will say—to encourage people to check out my book—is that I wrote it because I didn’t see another one like it. Scholars and journalists have been good at documenting right-wing threats to literary freedom—of which there are many, especially in the US. But they go quiet when it comes to the Left.

And that’s where the real power lies in publishing. It’s not that the Left is trying to ban books from K–12 school curricula. That’s more the Right’s domain. The Left’s influence is behind closed doors—editing policies, acquisition practices. And publishing is a very liberal ecosystem. These are the people shaping what’s on the shelves at Barnes & Noble or Amazon.

Even the reviews on Kirkus—they’ve all been touched by this phenomenon, whether we call it cancel culture or wokeness.

And although this isn’t my main research area anymore—I’m done writing about it—the people I know in publishing all say the same thing: it hasn’t disappeared.

South Park may say “woke is dead,” and that might be true in some circles. It’s not exactly thriving in the Oval Office right now. It’s not as though Penguin Random House has suddenly launched ten heterodox imprints and is now interested in a broad range of voices. Nor is the English department at Princeton seriously reconsidering the many great scholars who’ve been effectively blackballed by academia.

Woke is still very much alive—and thriving—in the very epicentres that originally exported it.

ZB: And that’s why your book is so important. I really recommend everyone read it. I’ll link it in the show notes. It’s a fascinating read—scary, but necessary.

Thank you so much for putting your neck out there and creating this brave piece of work.

AS: Thanks. I appreciate that.

ZB: Thank you.