Canada

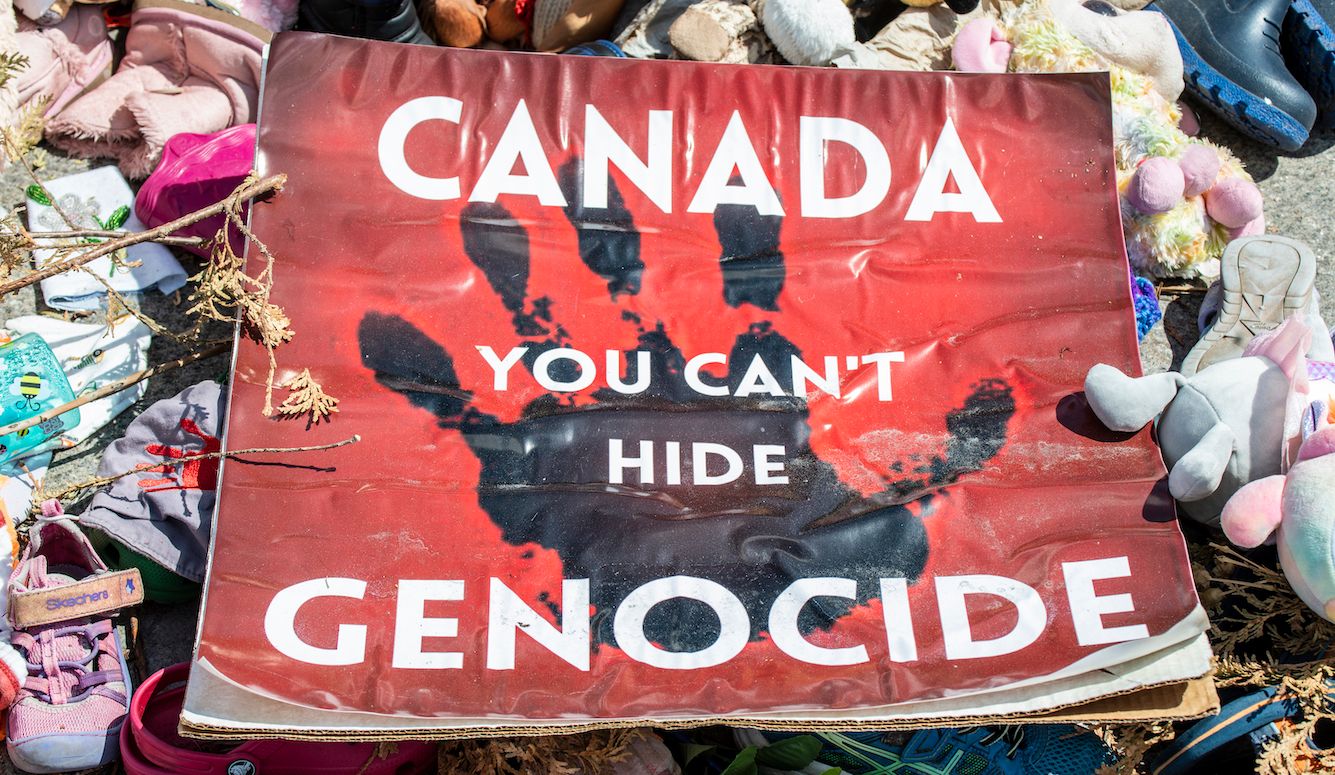

That Time Canada Rebranded as a ‘Genocide’ State

In a new book, Tristin Hopper documents the radicalised brand of social-justice politics promoted by ex-Prime Minister Justin Trudeau—including the lurid suggestion that his own government was murdering legions of Indigenous women.

This is the story of how, in 2019, Canada became the first (and, to this day, only) country to declare itself guilty of committing an ongoing genocide against its own citizens.

To outsiders, who (correctly) view Canada as a humane democracy, the tale will seem bizarre. But to Canadians, there was a certain twisted political logic to it—at the time, at least.

In the late 2010s and early 2020s, back when my country was still ruled by Justin Trudeau, Canada’s progressive elites bought into then-ascendant social-justice manias with a born-again fervour that was arguably unmatched in any other nation. This was a time, readers will recall, when college students were busily confessing their internalised white supremacy and racist thought crimes to one another on social media. Seeking to ingratiate his Liberal Party with this young demographic, Trudeau extrapolated their cultish movement on a national scale.

His rhetorical style became increasingly manic, as one social-justice slogan led to another; with each being rapturously liked and retweeted on social media. In short order, Trudeau was describing his own country with the kind of apocalyptic rhetoric one typically associates with, say, the Holocaust, Holodomor, or Rwandan Genocide.

In this regard, Trudeau’s first truly epic act of national self-incrimination took place at a 2019 women’s conference in Vancouver. The PM had just been handed the final report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG), a probe he’d authorised as a means to investigate the high rates of homicide committed against Canada’s female Indigenous population.

As it turned out, however, the MMIWG report authors’ most prominent demand had nothing to do with the technical details of criminal investigation. Instead, they were focused on language: They wanted homicides targeting Indigenous women and girls to be described as an ongoing “race-based genocide” perpetrated by Canadian society at large.

Murder wasn’t the government’s only instrument of genocide, the authors claimed. Higher rates of Indigenous heart disease and suicide attempts were also described as foreseeable results of Canadian policies that are “explicitly genocidal.”

Canadians tend to feel guilty about the genuinely shameful way their country treated Indigenous peoples at many historical junctures (more on this below). Because of this high baseline guilt level, it is often seen as taboo (especially among journalists) to push back against even the most obviously counterfactual claims made on behalf of Indigenous peoples. And the MMIWG report was a case in point: the inquiry’s insistence that Canada was in the midst of an active genocide was reported uncritically by most media outlets.

Some public figures did speak out against this hyperbolic use of language—such as Roméo Dallaire, the retired general who’d been in Rwanda during that country’s (actual) genocide in 1994. Yet Canada’s most important public figure—Trudeau himself—accepted the inquiry’s conclusions without reservation; even if this meant that he was now signalling his status as leader of a nation that, day in, day out, under his own watch, was committing a genocide against its own population.

“Earlier this morning, the national inquiry formally presented their final report, in which they found that the tragic violence that Indigenous women and girls experienced amounts to genocide,” he told his Vancouver audience. Trudeau then paused for nine seconds to accommodate his desired reaction—which consisted of cheers and applause.

When Trudeau took office as PM in 2015, Canada was still marketing itself to the world as a model of tolerance and multiculturalism. Suddenly, all of that was turned upside down: “Ongoing genocide” became an accepted form of national self-identification within Canadian political discourse. One Member of Parliament representing the left-leaning New Democratic Party (NDP), Leah Gazan, has employed the term more than forty times during remarks made in the House of Commons (and has even tried to criminalise naysayers as “denialists”).

This was actually the second time that the Canadian government had formally admitted to some form of genocide. The first was in 2015, when Trudeau, then freshly elected as PM, formally accepted the final report of the country’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC).

That six-volume report emerged from a seven-year inquiry into the country’s Residential Schools, which operated during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries as a means to assimilate Indigenous children into white society. In many cases, families were forced to send their children to these boarding schools against their will. Some of those children never came home (usually because they’d succumbed to tuberculosis).

Compared to the 2019 MMIWG report, the 2015 TRC report was a model of meticulous scholarship. The TRC authors cited troves of archival documents in detailing how the Residential School system started, who ran it, where the schools were located, and how the children were treated. The commission held cross-country public hearings, and interviewed hundreds of former students, many of whom had never previously gone on record with their accounts—some of which included tales of brutality and sexual abuse.

In calculating the number of children who’d died after being enrolled in Residential Schools, TRC researchers chased down every verifiable death notice they could find, and sorted the names they came up with—about 3,200—into a public database. An eighty-three-page addendum to the final TRC report included charts plotting known student deaths by year, by region, and by cause (as noted above, disease was far and away the number-one factor).

The report included detailed maps showing the abandoned and unmarked cemeteries where the deceased were likely buried. The report also contained statistical data showing that, even at a time when child mortality everywhere was elevated compared to our own era, the overall death rate in the Residential School system was always far higher than the Canadian average.

Yes, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission used the G-word, but with an important qualifier. Obviously, the residential school system hadn’t been a program of organised mass murder. Rather, the TRC report concluded that the Residential School system had inflicted a cultural genocide—defined as “a systematic, government-sponsored attempt to destroy Aboriginal cultures and languages, and to assimilate Aboriginal peoples so that they no longer existed as distinct peoples.”

Whatever one thinks of the phrase “cultural genocide,” the Truth and Reconciliation Commission had the receipts for its underlying claims. Official documents from the time made clear that the point of Residential Schools had been to produce a generation of Indigenous children who were alienated from the languages and traditions of their parents. This mission was neatly summed up in a 1920 quote from Duncan Campbell Scott, the civil servant who’d been placed in charge of the system at its height: “Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic, and there is no Indian question, and no Indian Department.”

The National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls was a different thing entirely. From the beginning, its processes were dominated by veteran political activists with little apparent enthusiasm for statistics and archival research. The report’s introduction quotes heavily from Pamela Palmater, a Toronto academic who’d been a spokesperson for Idle No More, a 2012-era protest movement whose leaders tried to shut down the Canadian oil sector and shame the country into cancelling Canada Day.

Once ensconced at the MMIWG inquiry, these activists found themselves staring down an awkward fact: While Indigenous women had indeed been killed at a higher rate than other Canadian women, in 86 percent of cases in which the suspected killer’s identity was known, the killer himself was Indigenous, too.

One would think that such statistics would be of great interest to researchers (nominally) tasked with preventing Indigenous women from being killed. But that figure is cited only in passing in the MMIWG report; and even then, the authors dismiss it as “unreliable” without providing any contrary evidence. Indeed, they accuse the Statistics Canada officials who publish such data as “encouraging racism.”

Amazingly, in fact, the MMIW report contained almost no evidence of any kind. Across more than 1,000 pages, there isn’t any explicit criminological analysis of who was getting murdered, under what circumstances, where, and by whom. An addendum simply informs us that “there is no reliable estimate of the numbers of missing and murdered Indigenous women [and] girls.”

What really interested the authors was making sure everyone used the word, “genocide.” An addendum instructed doubters that existing definitions of genocide, such as the UN definition drawn up in the wake of the Holocaust, are deficient because they failed to consider the act “through a gendered lens.”

As to the question of how the Canadian government might hope to stop committing genocide, the MMIWG’s “calls for justice” recommend a process of “decolonization,” including the incorporation of “gender-inclusive” language on government forms, and “a guaranteed annual livable income” for everyone in the country, Indigenous or otherwise. Thus did an inquiry conceived as a tool to prevent murder become a kitchen-sink wish list of progressive political demands.

To this day, Indigenous leaders will often say that Canadians who want to understand the harms caused by Residential Schools should read the TRC report. The MMIWG report, by contrast, came and went as a thicket of repetitive academic jargon. The document had little impact beyond the original flurry of news stories.

The word “systemic” appears 109 times in the main MMIWG report. “Patriarchy” appears ten times. “Lived experience” appears 47 times. “Colonial” and its variants appear 379 times. And the term, “2SLGBTQQIA” appears no fewer than 1,197 times.

In case you’re wondering what that latter term means, it’s “two-Spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning, intersex, [or] asexual.” Although the inquiry had been struck to figure out why so many Indigenous women and girls were being murdered, organisers subsequently pushed for it to encompass every conceivable letter or number under (what they called) the “2SLGBTQQIA” umbrella. In the foreword to the report, it was explained that these alphanumeric constituencies had been lumped in because those groups were all part of “traditional” Indigenous societies before they’d been “ostracized through colonization.”

The tale of these two inquiries provides a stark illustration of just how completely Canada’s progressive leaders succumbed to the social-justice radicalism that marked the Trudeau years. As recently as 2015, a Crown inquiry given the sensitive task of probing one of Canada’s darkest chapters would return with a scholarly archive of real facts that is studied to this day. Just four years later, a team given the more closely defined task of figuring out how to keep Indigenous women from being murdered churned out a brick-thick compendium of faddish bafflegab about “intersectional systems of oppression.”

Not surprisingly, the MMIWG inquiry appears to have done nothing to stop the crisis it was supposed to address. The year its report was published, forty-eight Indigenous women were victims of homicide in Canada. In 2023, four years after Trudeau dramatically basked in applause during his landmark announcement in Vancouver, the victim tally was fifty.

Adapted, with permission, from Don’t Be Canada: How One Country Did Everything Wrong All At Once, published by Sutherland House. Copyright @2025 by Tristan Hopper.