film

Joys Known Only to the Insane

In Hereditary and Midsommar, Aster's characters search for their place in the world—and can only find it by embracing evil.

Isn’t the role of the artist to put your sickness in other people?—Ari Aster

Contains spoilers for Hereditary and Midsommar.

Hereditary and the Horrible, Hopeless God Machine

“Life is suffering,” says 38-year-old American filmmaker Ari Aster, who is given to cliché, and likes to make light of the darkness. After rising to prominence in the 2010s with his first two feature horror films, Hereditary (2018) and Midsommar (2019), and solidifying his style with the three-hour nightmare comedy Beau Is Afraid in 2023, Aster has established himself as a modern horror auteur under the production label A24. His films are probably best known for their apocalyptic yet absurd endings.

Aster often plays on the idea that our worst fears and phobias are actually completely rational and lucid. Consider a scene from one of the short films he made during his time at the American Film Institute, The Strange Thing About the Johnsons (2011), an incest romp about a son who molests his own father in a dreamy American suburbia. In one scene, to cope with his horrifying reality, the father is sitting in the tub listening to a self-help tape—voiced by Aster himself—which is saying something about how our attitudes create our reality, when the son kicks in the bathroom door and rapes him. This is Aster straddling the line between horror and hilarity.

Aster uses screenwriting to work through dark feelings of his own. “I’m a very neurotic guy. I’m hypochondriacal. I’m somebody who, I’m in a crisis until I resolve it, and then I replace it with a new one,” he recently told Vulture. “And I usually write in crisis. So for me, writing these films has been therapeutic because all of a sudden I can take out my anxieties and my worst-case scenario imagination on these characters and watch them navigate it, as opposed to navigating it to no end in my own life.”

Aster has described Hereditary as a family tragedy “that curdled into a nightmare.” The story centres on a miniaturist named Annie Graham (Toni Collette), her psychologist husband Steve (Gabriel Byrne), and their two children, sixteen-year-old Peter (Alex Woolf) and his twelve-year-old sister, Charlie (Milly Shapiro). Annie’s mother has just died and she delivers a funeral speech that conveys just how strained their relationship was, something that’s reflected in Annie’s chilly relationship with her own children.

One night, her son Peter asks to borrow the car to take to a “school barbeque thing.” Annie makes him take Charlie with him. There, Charlie has an allergic reaction to some nut-infused cake while Peter is off trying to get laid, and while en route to the hospital, she sticks her head out of the window to gasp for air and gets decapitated by a telephone pole when Peter swerves out of the way of a deer carcass. At a support group some time afterwards, Annie is approached by a strange woman named Joan (Anne Dowd), who tries to help her contact her dead daughter through a seance. But soon the metaphorical ghosts and demons turn literal.

It’s ultimately revealed that Annie’s mother was the leader of a demon-worshipping coven and Joan was her underling, and everything that’s been happening to the family has been part of an ancestral possession ritual to resurrect the demon King Paimon. He was born through Charlie but now Peter has been targeted as his new vessel. The tragedies pile up: The husband gets burned alive, Annie cuts off her own head with a piano string while floating in the air, and a bunch of naked people stalk the Graham home. The film ends with a resurrected Charlie, who is actually King Paimon, in Peter’s body, gazing mindlessly into space in a treehouse full of robed cult members as they erupt into a cry of “Hail Paimon!”

In the opening moments of the film, we zoom in on one of Annie’s miniature dollhouses that then grows to the size of their actual home, establishing a metaphor: These people have no more agency than dolls in a dollhouse. Aster has talked about how he wanted Hereditary to feel evil, as if the film itself were smiling at you while these innocent people are suffering. Like Peter Greenaway in The Cook, The Thief, His Wife and Her Lover (1989), he has explained, his aim as a director is to convey a god-like omniscience that feels nothing for its characters.

Themes of fate and choice pervade the story. Early on, Peter is spacing out in his high school classroom while the class discuss Sophoclean tragedy, in particular Women of Trachis—in which Heracles is brought down by his own hubris or, as a classmate puts it, his “arrogance, because he literally refuses to look at all the signs that are being literally handed to him the entire play.” The Graham family, too, are handed signs throughout the film, which they ignore. However, they have no choice. Like Heracles, their fates are predetermined. As a student says of Heracles, “the characters have no hope, they never had hope, because they are all just pawns in this horrible, hopeless machine.”

Hereditary is about the horrible, hopeless machine of our lives. Once Annie realises what’s happening to her family, she does everything she can to stop it. She is even willing to give her own life to spare her remaining child, Peter. Annie tries to burn Charlie’s drawing book, which acts as Paimon’s link to this world, despite believing that she will be burned alive in the process. But when she throws the book into the fire, it’s her husband who is spontaneously set aflame. “Even that scene is meant to play as Annie’s big redemptive moment, she’s going to sacrifice herself for her son,” Aster has noted. “It’s a beautiful gesture but part of the cruel logic of the film is it’s an empty gesture. Ultimately, it’s not her choice to make. She thinks there’s a design here and she can end things if she sacrifices herself. But there’s no design and there are no rules. There is a malicious logic at play.”

Annie’s miniature replicas, her little dollhouses, are her way of distancing herself from reality. There are moments where we can’t tell what’s real and what’s dream, what’s a miniature and what’s lifesize, what’s a literal or metaphorical ghost. “Freud … says that horror is when the home becomes un-homelike, unheimlich,” Aster said in a conversation with Film-Comment. “I wanted to make a home that became something malign and unrecognizable by the end. And that’s where the miniatures come in … It’s a replica of the real thing. It is the thing, but it’s not the thing. That is your mother, but it’s not your mother.”

And yet, all the scenes of horror soon become so exaggerated that the film veers into comedy. The problems of real life are replaced by floating headless women, nude cult members, weird rituals, and violence too graphic to seem real. As Aster puts it, “For me, a lot of what makes me laugh is just the sadism of Hereditary. Charlie’s head coming off makes me laugh. I recognized that the goal is to affect people, but the idea of them being affected by that makes me laugh.”

Midsommar: A Fairytale Murder

Aster’s second feature film, Midsommar (2019), follows a crumbling modern relationship set against the backdrop of a once-in-a-lifetime Swedish midsommar festival. It couples the folk horror genre with the classic break-up movie. In contrast to Hereditary—a family drama that bleeds into a nightmare—Aster has described Midsommar as a tragedy that bleeds into a fairytale.

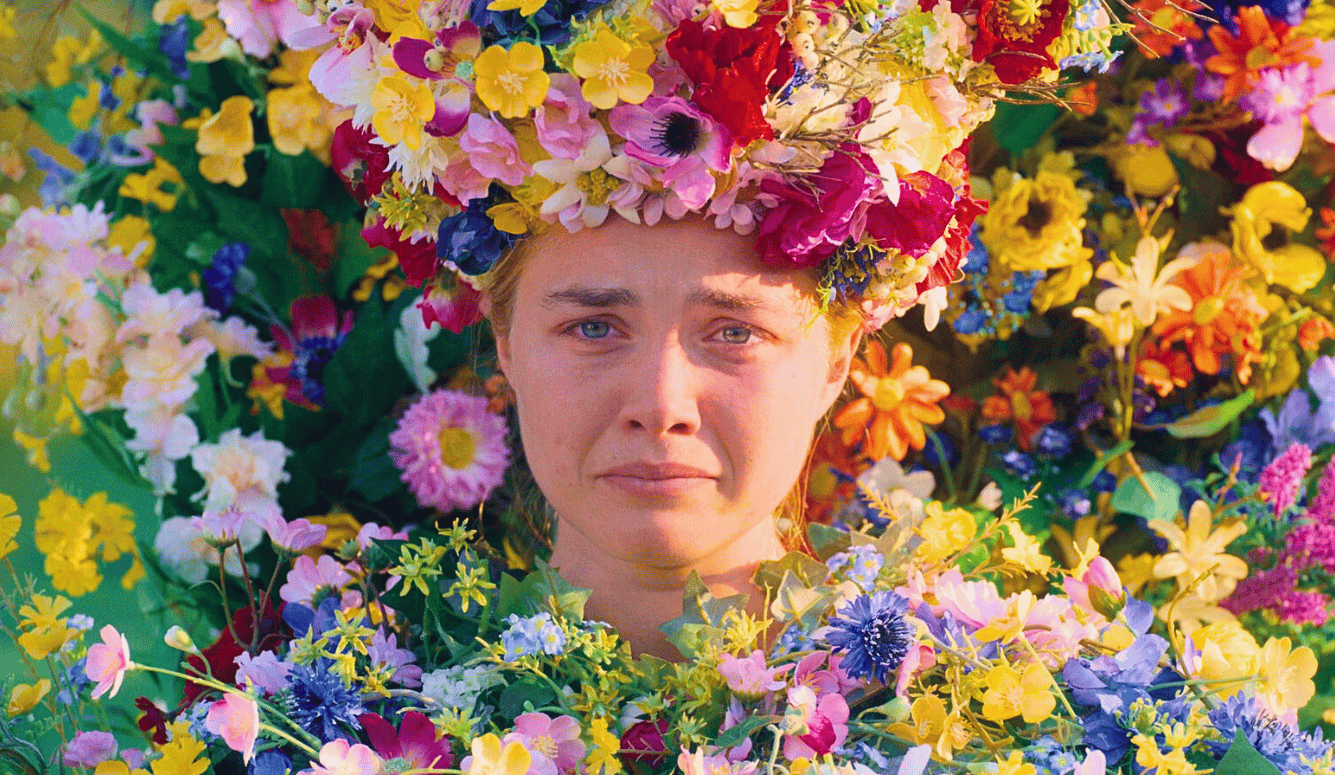

Midsommar opens with a terrible event that leaves the protagonist orphaned and alone in the world. Dani, played by English actress Florence Pugh, is a psychology grad student ensnared in a dead-end relationship with her indifferent boyfriend, Christian (Jack Reynor), when she discovers that her bipolar sister has just killed both her parents and herself in a murder-suicide. The tragedy compels Christian to stay with Dani out of guilt, while she stays with him out of sheer need.

Although her grieving process has barely begun, Dani reluctantly agrees to go with Christian to visit the home community of their Swedish friend, Pelle (Vilhelm Blomgren). The Harga, Pelle’s “family,” are a bunch of pre-modern hippie farmers. They are initially welcoming towards their guests, but their customs and ceremonies grow increasingly sinister and violent and soon people start disappearing.

But even as the Harga become more hostile toward Christian and the other visitors, as the film progresses they become increasingly loving toward Dani. At the end of the film, Dani wins a hallucinogenic folk-dance competition and is crowned May Queen of the Harga, while Christian and his friends are murdered. In a final ceremony, the decorated corpses are thrown into a big yellow barn and set alight as the community watches. The last shot of the film shows Dani smiling as she watches her ex’s body burn.

Christian’s behaviour as a boyfriend is supposed to make this ending feel satisfying. Early on, he downplays the seriousness of the situation with Dani’s sister—he plans to abandon his grieving girlfriend to go on a jaunt with his friends—and, when she discovers his plan, manages to drag her along with him. He forgets Dani’s birthday. And Dani blames herself for all these things. It’s Christian and his friends who are the film’s real antagonists, while the Harga are there to facilitate her healing process and help her discover her true self. “So hopefully, you go in thinking that the Harga will be the villains,” Aster said in an interview with Vox. “Then you realize that it was Christian, all along.” But the film does not exactly have a happy ending. Dani ends one unhealthy relationship, with Christian, just to enter into another, even unhealthier one with the Harga. As Aster has said, “I … hope it’s funny, but I hope that the laughter catches in the throat.” This moral ambivalence pervades the film. Christian and his friends may be annoying, but they don’t do anything to remotely justify their grisly fates, while Dani is an equally irritating character, who demonstrates very little agency. The one confident choice she makes is to betray Christian and condemn him to death.

In the tradition of folk horror, the visitors commit minor offences against the Harga—accidently pissing on an ancestral tree, taking pictures of a holy book—for which they are punished to an absurd degree. The triviality of their offences is the point, Aster has said. Their deaths happen off-screen:

There was a perverse pleasure in eschewing the thing that everybody’s there for: the kills. For me, there’s something more disturbing about barely paying any attention [to the deaths], because these are lives that are being totally dismissed and shrugged off, and that’s the attitude of the community, so that becomes the attitude of the film.

In Midsommar, Aster portrays beliefs that he found beautiful and compelling, drawn from various European midsommar traditions and spiritual movements. “If anything, what ties them all together is a philosophy of mindfulness, staying connected to your life and to the people in your life and to the world around you,” Aster has said. “Being present in your life. Which is something that the Americans in the film aren’t. For me, that was very important.” “I don’t see them as a cult,” Aster has asserted of the Harga. “This is a fairytale, and they really are exactly what Dani needs. For better or worse, this is a wish-fulfilment fantasy… We begin as Dani loses a family, and we end as Dani gains one.” This is a strange thing to say of the Harga who are a bunch of homicidal Nazi freaks. What the film shows is that the flip side of a utopian community in which people are deeply united in a chosen family is a descent into collectivism of the most terrifying sort, with the concomitant abdication of personal responsibility. This is a community in which the individual has been totally annihilated, where there’s no real privacy or aloneness—the total opposite of modern life.

A scene about halfway through the film shows just how senseless and nihilistic such traditions can be. The Harga are to perform an Ättestupa ceremony, in which two of the elders who have reached the end of their life cycle are to die of their own volition by jumping off a cliff onto a rock. When one of them misses the mark and shatters his leg into bits, a few of the community members proceed to bash his face in with mallets instead. As one of the elders explains to the horrified visitors: “What you just saw was a long, long observed custom. Those two who jumped have just reached the end of their Harga life cycle, and you need to understand it as a great joy for them… We view life as a circle, a recycle… Instead of getting old and dying in pain and fear and shame, we give our life, as a gesture. Before it can spoil.” Ironically, Aster has said of the Harga’s connection to Dani, “These people speak a language of empathy, which is something that is missing in Dani’s life. There are several scenes that could be read as just horrific. Or they could also be read as therapeutic for the character, where she is encouraged to face the unfaceable.” After the suicide ceremony, Pelle tells her that the community has provided him with a family, after his own parents died in a fire. “I never had the chance to feel lost because I had a family. Here. Where everyone embraced me and swept me up. … I have always felt held.. by a family. A real family.” Pelle pointedly asks, “Dani, do you feel held by [Christian]? Does he feel like home to you?”

Pelle plays a similar role in Midsommar to that of Joan in Hereditary, a kind of pied piper figure luring the victims to their fate. But unlike Joan, Pelle seems to genuinely mean well and there’s even a hint of romance between him and Dani. As Aster told The Atlantic, this gives the film “the trajectory of a high-school comedy. It’s about a girl who everyone knows is with the wrong guy, and the right guy is under her nose.” By the end of the movie, Dani has transcended her pain, has found a family and a home and real love—but she has become evil in the process.

Midsommar is about the lengths we will go to feel at home in the world. In Hereditary, tragedy breaks the family apart and destroys them. In Midsommar, tragedy leads Dani to find a family. The last lines of the screenplay read, “A SMILE finally breaks onto Dani’s face. She has surrendered to a joy known only by the insane. She has lost herself completely, and she is finally free. It is horrible and it is beautiful.” Horrible and beautiful: this is also an apt description of Aster’s films.