Boardgames

Class Struggle Meets Game Night

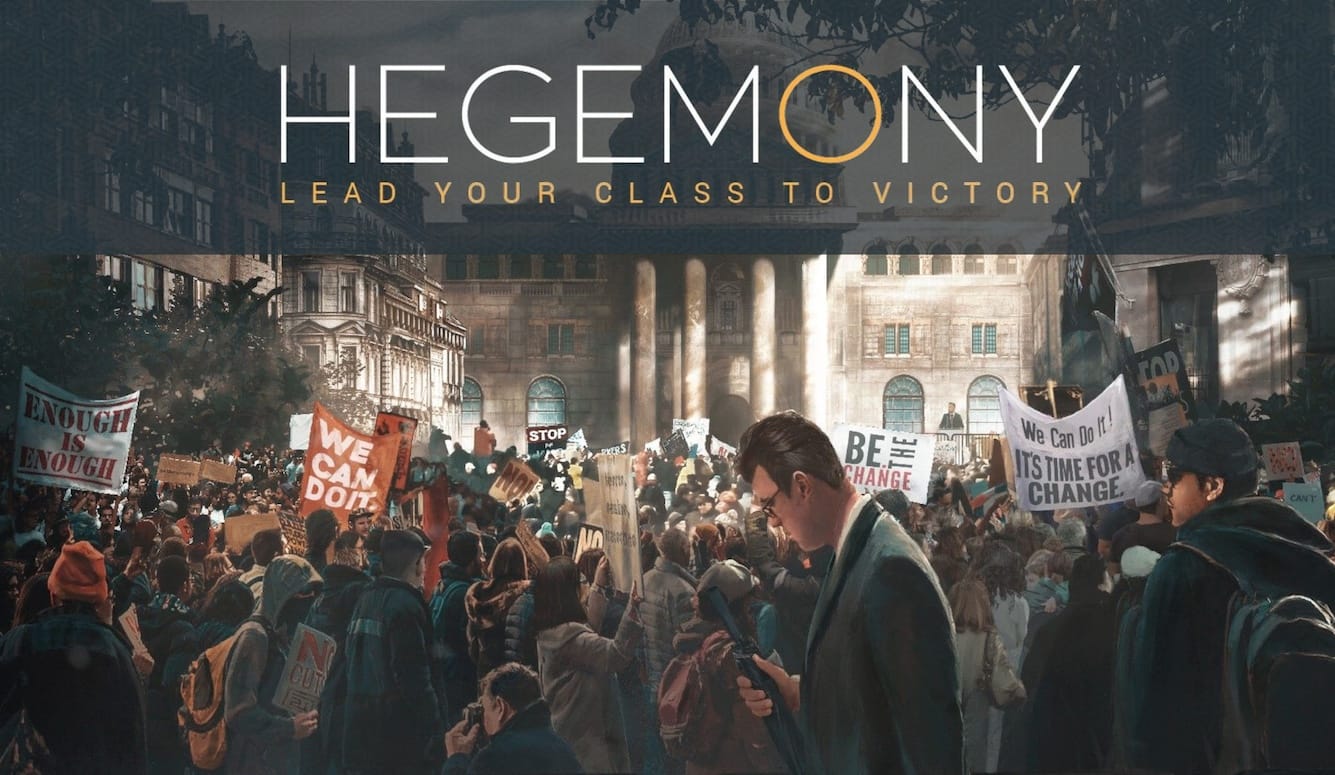

In ‘Hegemony,’ board-gamers take on the role of wage workers and plutocrats fighting for societal supremacy.

In 2017, a Greek Cypriot policy wonk named Varnavas Timotheou got the idea to create an “educational board game based on the academic principles of political sciences, political economy, and economics.” As elevator pitches go, it sounds like a complete dud. And yet, the game he ultimately produced in 2023, Hegemony: Lead Your Class to Victory, has been a huge commercial success, and now ranks as the 45th most popular title on the widely followed BoardGameGeek web site. Earlier this month, I sat down and played it for the first time.

This wasn’t a game I’d been especially eager to try, having been put off by its explicitly “educational” premise. As I’ve written here at Quillette, it’s absolutely true that a good board game can teach players a lot about the world—including the history of Norse-Indigenous warfare (Greenland), the physics of space travel (High Frontier), and the art of brinksmanship (Chinatown, No Thanks). But in these artfully produced games, the learning happens by accident. It’s very different when a game creator earnestly announces that education (or, worse yet, moral improvement) will be his game’s mission.

Put another way: Peas taste great when they’re embedded in samosas. They’re much less appealing when someone invites you to eat a whole bowl of them.