Iran

Discussing the Iran–Israel War with an Iranian Dissident | Quillette Cetera Ep. 48

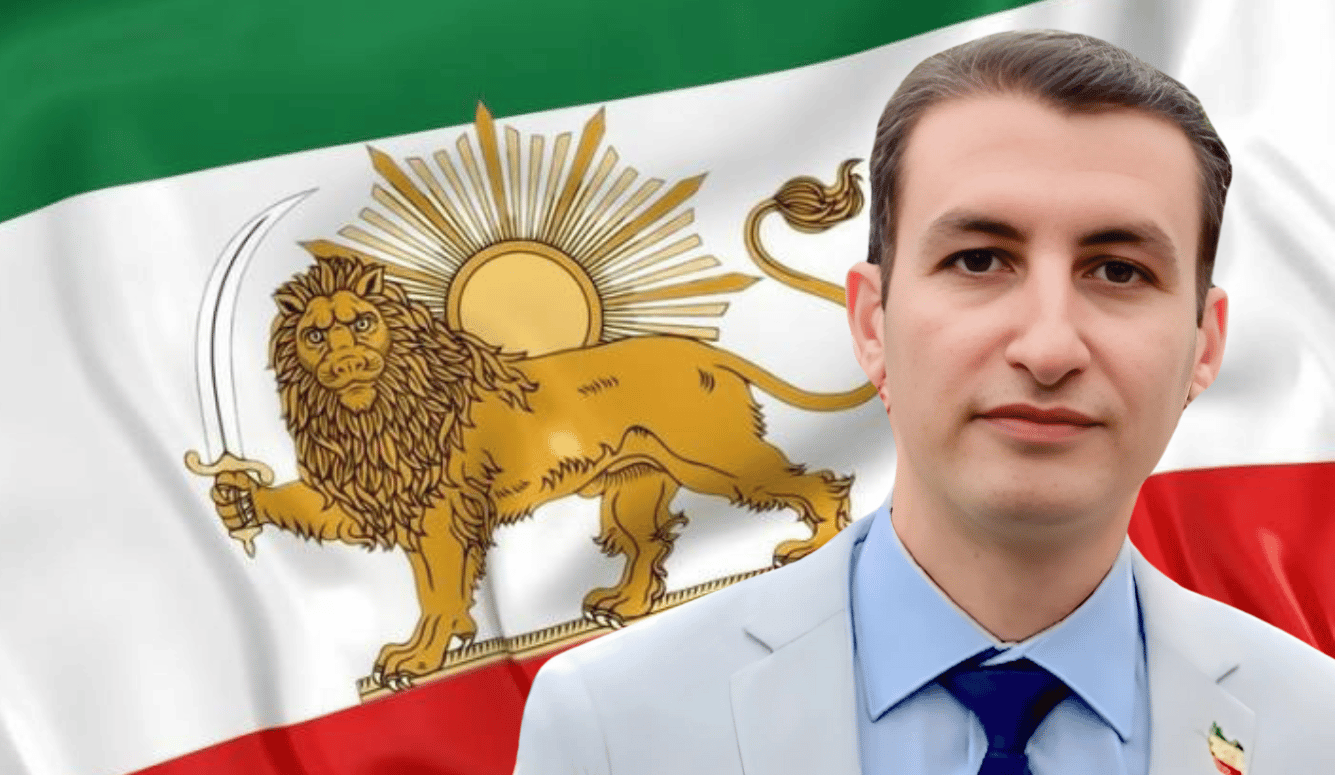

As missiles fly between Tehran and Tel Aviv, Iranian dissident Danial Taghaddos joins Zoe to explain what the West gets wrong about the regime, the nuclear threat, and the future of his homeland.

As missiles fly between Tehran and Tel Aviv, I’m joined by Iranian dissident Danial Taghaddos to make sense of a rapidly escalating war—and what it means for the future of Iran, Israel, and the region. Danial moved to Australia in 2018 and became politically active during the 2022 Mahsa Amini protests. A royalist and advocate for a return to constitutional monarchy under the Pahlavi dynasty, he’s emerged as a compelling voice in the Iranian diaspora, challenging both the Islamic Republic and the Western narratives that often obscure the regime’s abuses.

In this episode, we talk about Iran’s nuclear ambitions, what the regime actually wants from this war, and how Zoroastrianism and Persian identity shape Iranian views on Israel. We also unpack how the Iranian diaspora organises abroad, why many Iranians support Israel despite the regime’s propaganda, and how the West continues to misunderstand the Islamic Republic. From public executions to political repression—and threat of Islamism and regime spies operating in the West—this conversation is a sobering look at the human cost of Tehran’s ambitions, and a hopeful one about the people resisting from within and without.

Transcript

Zoe Booth: Danial, thank you so much for joining me here today on such short notice.

Danial Taghaddos: Thanks for having me.

ZB: Israel and Iran are currently exchanging fire, and I hope your family in Iran are okay. Could you explain a little bit about what’s happening in Iran right now—what you’re hearing from your friends and family?

DT: What I hear mostly is that currently military sites are being attacked in Iran—mostly military sites, missile depots, and nuclear facilities. These are very targeted strikes against specific individuals. That’s what I’ve seen in the news and what I hear. I don’t talk much about the news or what’s going on with my family back there, because they might get into trouble. But from public posts on social media and from the few anonymous people I do speak with, the strikes appear to be specifically targeted—not just random bombings of buildings.

ZB: I’m hearing the same. I have a friend in Bandar Abbas in the south of Iran who, thankfully, is safe. I asked him, “Where are you sheltering?” and he said, “In my house.” And it struck me—most Iranians don’t have bomb shelters, because Iran doesn’t regularly experience bombing of civilians. But Israelis do, because their neighbours often target civilian centres, which is really unfortunate. Could you explain why it’s not a good idea for the Iranian government to have nuclear weapons?

DT: Well, they’ve threatened to wipe Israel off the face of the earth—and that’s not a new threat. They’ve been making it since their inception. This goes back to a religious war against Jews. Historically, since the formation of the Islamist movement in the 1900s and its alliance with communist and socialist movements in the 1970s, both have harboured hostility toward Israel. Iran, in their view, is a prize—a tool to fulfil their dreams, one of which is to eradicate Israel.

Israel is a recognised nation state and a member of the global community through the United Nations. That’s why allowing Iran to develop nuclear weapons is so dangerous. If your neighbour openly threatens to kill you, you wouldn’t want them to have even a knife, let alone a nuclear weapon. That’s the basic rationale.

ZB: Some people would say, “But Danial, other countries have nuclear weapons. There’s speculation that Israel has one. Doesn’t Iran also have the right to defend itself?”

DT: Iran as a nation state absolutely has the right to defend itself. That’s why Iranians fought back when Iraq invaded in the 1980s. Every country has that right. But that right does not include exporting terrorism, forming militias in other countries, and destabilising economies and governments.

As a patriotic Iranian, I do believe Iran should have a strong military to defend itself—especially considering the number of times we’ve been invaded in the past century. But that doesn’t justify threatening to annihilate another country and then trying to realise that threat by developing nuclear weapons.

Pakistan and India have nuclear weapons, and they constantly threaten each other—that’s not a situation any country should aspire to. And while major powers like Russia and the United States also have nuclear arsenals, we hear terrifying threats of nuclear war from them, too. But when the group running Iran is ideologically committed to such threats, adding nuclear weapons into the mix is catastrophic.

DT: It could be that there are no nuclear weapons and that it’s a false narrative. But it could also be true. We, as dissidents to the regime, have been calling for its dismantling and for Iran to return to a normal state—what I believe should be a constitutional monarchy. We’ve been pushing for this for 47 years, the entire lifespan of the regime. But no one listens or gives that idea a fair opportunity.

Maybe the narrative about Iran building nuclear weapons is false. But is it a risk worth taking? No one wants a nuclear weapon detonating anywhere in the Middle East—not in Iran, not in Iraq, not in Israel. So wouldn’t it make more sense to remove the threat entirely and dismantle the regime?

ZB: That makes a lot of sense to me. But sadly, it seems many people either don’t know or don’t care. Especially in Australia, I think people would care more if they heard voices like yours. That’s why I’m so intent on amplifying your voice—and the voices of other truly patriotic Iranians who want not only good for Iran, but for the rest of the world. Iran has such a rich, unique culture. It’s different from many countries in the Middle East. I think Australians often assume Iran is just like any other Muslim country in the Middle East. Can you explain a bit about what makes Persians or Iranians different from other Arab countries?

DT: Well, if any Australian has come across Persians in their life—which I believe many people around Sydney and Melbourne and Brisbane, like in big cities, might have—they would, after a while, be able to tell the difference between an Iranian and any other Arab person they would meet.

First of all, the language is different. So Iranians—just like Israelis who speak Hebrew and not Arabic—Iranians speak Persian, not Arabic. Also known as Farsi. Yes, there are dialects and there are regions, particularly in the south-west, where some speak Arabic—but that’s a minority.

DT: They’re not the majority of the people, even in that area. That’s the first difference. Culturally and religiously, Iranians are not aligned with the other Arab nations. In fact, Iranians and Arab nations have had tensions for many decades over various issues. There’s always a bit of conflict in the Middle East—even between neighbouring cities within the same country, you can observe that.

Iranian culture includes dancing, poetry, beautiful traditions, and social gatherings. If you’ve ever been to any of the ceremonies that Iranians celebrate, like Nowruz, you’ll see how joyful and festive people are. They’re known for that.

ZB: Yes, there’s a lot of brightness. And at Nowruz, on the table you put an egg and flowers, and I think they symbolise fertility and life, right?

DT: There are symbols of fertility, life, and all of that. We’re talking about thousands of years of civilisation—three thousand at the very least, and lost civilisations long before that. Claims go up to ten thousand years. Scientific findings suggest it might even be more than that.

So we’re talking about a continuous civilisation in Iran. That’s what sets it apart from other nations in the region, which have experienced interruptions and upheavals—be it through nationalist movements, religious changes, or other forces. That continuity makes Iranians different.

ZB: Can you talk about Zoroastrianism and the Parsis?

DT: Yes, well, Zoroastrianism was the major religion in Iran up until about 1,500 years ago, before the Arab conquest. And it still lives on within Iranian culture and ceremonies—Nowruz is one of them, along with Yalda and many others. There are multiple celebrations throughout the year—I believe there’s at least one every month.

You can see the beliefs of Zoroastrianism woven into the fabric of Iranian culture and society—values like peace, and the importance of good thoughts. The very idea of valuing thought and intellect has its roots in Zoroastrianism.

ZB: And from what I can see, Parsis—which I believe is another word for Zoroastrians—and Jews have so much in common, because they’re both persecuted groups in the Middle East. They’re also both groups that are inconvenient minorities. They’re small in number but achieve a lot and really emphasise education. So the women end up becoming very well educated and things like that. My colleague Iona, who works at Quillette, she’s Parsi but from Pakistan.

DT: Yes, so Parsis were the original Zoroastrians who fled Iran to India at the time of the Islamic conquest. They are part of the original Iranian heritage, you might say. And yes, they mirror the Jewish community in that they usually form closed communities, due to restrictions of the time or the ruling power.

For example, the king of India told them they could live there but couldn’t propagate their religion, couldn’t advertise it, and couldn’t marry Indians freely—men couldn’t marry women or vice versa. So they had to keep within themselves. Much like what happened to Jews in Europe before World War I and II—closed communities within themselves.

Because of the teachings of their elders, they’ve learned to value wealth, achievement, and merit—and that leads to successful, high-achieving communities.

ZB: That’s a fascinating culture. I was wondering—how openly can you celebrate Nowruz or any other religious holiday or custom that isn’t Islamic? For example, are there Jews in Iran? We often hear there aren’t, but I was actually looking on Google Maps to see if there were any synagogues in Tehran, and I saw that there were. I also know many Iranian Jews who had to flee in the 1980s. Could you tell me what it’s like—how free are religious minorities to practise their religion in Iran?

DT: Religious minorities like Zoroastrians, Jews, and Christians—though not the Baháʼís, they’re treated differently—are officially recognised by the regime. But because of that recognition, they’re also heavily controlled. They’re not allowed to propagate their religion or invite others to convert. The rules around marriage are very strict, too. For example, a non-Muslim man cannot legally marry a Muslim-born woman—it doesn’t matter if she’s practising or not. It’s not purely a religious issue; it’s a governmental law.

The leaders of those religious groups are tightly monitored. Yes, there are synagogues and Zoroastrian temples in Iran, but access is limited and controlled. In many cases, even Zoroastrians themselves won’t let outsiders in, for fear of persecution. And the regime certainly doesn’t allow conversions. Christians also face significant persecution. I know of several priests and Christian leaders who’ve been prosecuted—some even executed—for violating Islamic law.

So while the regime presents a façade—claiming that Christians, Jews, and Zoroastrians live freely in Iran—it’s misleading. They may be tolerated, but they’re not free to practise their religion as they would be in a country like Australia. The Baháʼís, in particular, are in a completely different situation. They’re actively persecuted.

ZB: Who are the Baháʼís?

DT: The Baháʼís emerged from a sect of Shiite Islam in the 1800s. Because of that, the Shiite clergy despise them even more than other religious minorities. They accuse them of being connected to Jews and to Israel—they’re considered enemies of Islam, of God. As a result, Baháʼís face intense and systemic persecution. They’re banned from holding jobs, attending university, or marrying Muslims. It’s a very grim situation.

Unfortunately, the Baháʼí community tends to stay quiet about this persecution because they consider themselves non-political. But that silence often means the extent of their suffering isn’t widely known.

ZB: Growing up in Iran—firstly, did you grow up in Tehran or elsewhere?

DT: I grew up in a smaller city just outside Tehran, in the south-western region. It’s a mixed area, with both Arabs and Persians. So I had exposure to different cultures within Iran.

ZB: And what were you taught about Israel and the West?

DT: My family didn’t hold strong views one way or the other, but of course, the regime has a vast propaganda machine. It permeates everything—education, media, online platforms. There’s also very tight internet censorship. If you want to access outside information, you have to be quite tech-savvy—use VPNs, find ways around firewalls. So, yes, I was exposed to all that propaganda growing up. But thankfully, information still finds its way through.

ZB: It clearly didn’t brainwash you. And I’ve found that most Iranians I’ve met are very intelligent and technically skilled—many are engineers or IT specialists here in Australia. Why do you think the propaganda doesn’t seem to affect Iranians as deeply as it might in places like Gaza?

DT: Part of it goes back to culture. Iranian culture values peace, coexistence, and prosperity. Historically, Iranians have valued monarchy—not necessarily as worshipping a king, but as aspiring to live well, to be prosperous, elegant, and cultured.

You see that in the humour and stereotypes about Iranians—they love to dress well, drive fancy cars, and look sharp. That aspiration toward prosperity means they’re naturally less inclined to embrace radical ideologies. You can’t be both an ideologue and a successful businessperson, for example. If you want a thriving business, you need peaceful relationships. You need to welcome all kinds of people.

This mindset runs deep in Iranian culture. We want to build connections, not conquer. That’s why the propaganda of the Shiite Islamic caliphate doesn’t resonate. It goes against who we are.

DT: Even some of the most religious Iranians—practising Muslims—are against this regime. Their faith is personal. They might pray five times a day, believe in Allah, and follow Islamic teachings, but they don’t believe those beliefs should be imposed on others. I have relatives who think like that—who despise the regime but are still devout Muslims.

ZB: So Islam itself isn’t the problem, per se.

DT: Political Islam is the problem. Islam as a personal faith is not. But once you try to turn religion into the basis of governance—once you write the laws of a nation based on the Quran or religious doctrine—you run into disaster. It’s simply not compatible with modern society. Political Islam is the issue. Personal belief, within the bounds of secular law, is not.

ZB: Yes, and I’ve heard that “Islam” literally means “submission” or “to bow down.” And the way political Muslims explain it, they say there must be a theocracy—because if there’s a government above Islam, it’s not truly Islamic. So, in that view, it becomes very hard to separate church and state. Jews, by contrast, have always lived in the diaspora and have always had that separation.

DT: Exactly. In Islamism, all power belongs to Allah. Any authority not rooted in Islam is illegitimate. That’s written in Islamic scripture. If anyone disagrees, they’re welcome to try to prove me wrong, but they can’t. I’ve studied it, and I’ve lived it.

So yes, political Islam views any non-Islamic government as illegitimate. The only way to deal with that, in their view, is through jihad—waging war to impose the rule of Islam. That’s what we see playing out in the Middle East.

ZB: And that’s the inevitable clash between Islamism and the West, isn’t it? Liberal democracies only work when everyone respects freedom of religion and diversity of belief—not when one group insists their religion must dominate.

DT: True.

ZB: It’s something we talk about a lot at Quillette. I became especially interested in it after 7 October. Could you explain a little about why so many Iranians support Israel and the Jewish people?

DT: First, it’s because Iranians are peace-loving and want to coexist with all nations, including Israel. We have a long shared history—going back 2,500 years. But the bond didn’t end there. During World War II, many Jewish refugees fled to Iran. There are openly Jewish communities in Iran rooted in that history.

Then, over the past 47 years of the Islamic regime, Iranian resources have been used to fund wars across the region—in Palestine, Lebanon (with Hezbollah), and Syria. Many Iranians now resent anything associated with that cause. They call it “the promise of Palestine” and are disillusioned with it.

The 7 October attacks—in which civilians were massacred at a music festival, in their homes, including women, children, and the elderly—shocked people. It sparked a new level of awareness and sympathy for Israelis.

DT: Also, in March 2023, Reza Pahlavi, the Crown Prince of Iran, visited Israel and met with Israeli government officials. He’s very popular in Iranian opposition circles. He’s seen as the only viable alternative to the regime—distinct from both socialists and Islamists. His visit created a political shift in Iran’s diaspora, favouring Israel. So when the October 7 attacks happened, many Iranians followed his lead, stood with Israel, attended rallies, and condemned terrorism.

ZB: It’s been beautiful to witness. I’ve attended many of those rallies. I’m not Jewish, but I feel very connected to the community. That’s actually where I first saw you—at a rally. I noticed this flag that looked like the Iranian flag, but with a lion on it. I thought, “Who are these people?” And since then, I’ve seen Iranians at nearly every Jewish or Israeli event—showing public support. It’s so moving.

Most other people, even if they do support Israel, are too scared to say so publicly. It’s not the fashionable or “correct” opinion. So it means a lot to see your support.

DT: Thank you. For many Iranians, though, speaking out publicly carries serious risks. If they put something on social media in support of Israel or against Hamas, they could be prosecuted, or their families could be targeted. So many remain silent—not because they don’t support Israel, but because they’re afraid.

I know many who do support Israel’s right to defend itself and reject the regime’s actions, but they haven’t been willing or able to pay the price to speak publicly.

ZB: And you have. You’re so brave. I know people here who use aliases because they’re terrified of regime spies. I’d love to hear more about that. I know you have work and family responsibilities, so I won’t keep you much longer. But can you tell us how you got the courage to speak out? And also how and why you came to Australia?

DT: I came to Australia in 2018 as a skilled migrant. I had been planning it for years. I’d wanted to migrate for most of my adult life because of the dire situation in Iran—initially due to the economy, but also because of political repression and censorship. I finally made it happen in 2018.

After a few years of settling in, I felt I owed something to my homeland. I’d lived there for thirty years, used its resources to get where I am, and I felt a responsibility to give something back—to those who don’t have the luxury of leaving or voicing dissent. So, I became politically active.

I got more involved after the 2022 protests—the ones that erupted following the killing of Mahsa Amini. That’s when I became actively engaged. And then, after the 7 October attacks, I started working more closely with the Jewish community.

At first, many in the Jewish community didn’t know that Iranians could be allies. Our first appearance was at a rally in Sydney in early November 2023, in support of the hostage families. There were only a handful of us, holding the old Iranian flags and posters. It felt important to be there.

DT: I see it as my duty and my debt—to represent the real voice of Iranian people. We want to correct the perception pushed by the media and the regime—that all Iranians support the Islamic Republic. They show regime-organised rallies on TV, where people chant “Death to Israel” or “Death to America.” But that’s not representative of ordinary Iranians. So we felt compelled to make our voices heard.

ZB: Have you faced much pushback—from pro-Palestinian activists, Islamists, the far Left, or even pro-regime Iranians in Australia?

DT: Yes, absolutely. The first backlash I experienced came from so-called reformist Iranians involved in the 2022 protests. They opposed the old Iranian flag—the one with the lion and sun—and told me I couldn’t wave it or go on stage with it. They said, “If you want to be on stage, you can’t hold that flag.” They tried to shut us down, even threatened to call police.

ZB: But this is Australia. It’s a free country.

DT: Yes, it is. But there are still rules—like “breach of peace.” If they control the stage or the event, they can use those rules to remove you, even here. That’s what happened.

Later, I realised those people weren’t just reformists—they were actually pro-regime. They didn’t oppose the Islamic Republic’s ideology; they just wanted a share of power. That was the first sign.

Then after 7 October, we were the first group to organise a rally in Sydney—on 22 October 2023—supporting Israeli victims and condemning terrorism. We chanted, “Iranians stand with Israel,” “We oppose terrorism,” and “This is not our war.” That provoked another wave of backlash.

Islamists don’t confront us directly—they know who we are. But leftist activists do. They try to smear us with labels. “Child killers” is one of their favourites.

ZB: Yes. Or, “You support genocide. You support killing babies.” It’s so disingenuous. Such bad-faith argumentation.

DT: Exactly. It’s a logical fallacy. They try to associate you with something horrific to destroy your credibility, even if your arguments are valid. It’s very close to a straw man fallacy.

ZB: Definitely. It’s taking your views and twisting them into the worst possible interpretation. Are there Iranian spies in Australia? I’ve heard that in the US, Roya Hakakian exposed a regime-linked professor at Oberlin College. The regime seems to place people in influential roles abroad—professors, media figures, policy advisers—often under the guise of Islamic or Middle Eastern studies. Do you see that happening in Australia?

DT: Yes. And Mahallati isn’t the only one. There’s also Seyed Hossein Mousavian—he was responsible for terrorism carried out by the regime in Europe. He served as an ambassador or second-in-command at one of the embassies. Now he’s a university professor in the US. Iranian Americans have tried to get him expelled, but without success.

In Australia, yes, there are individuals connected to the regime. Depending on how you define a “spy,” you can find them in various roles—academic, religious, legal. I won’t name anyone because of the legal implications, but I can confirm this is happening.

They might work as Islamic studies scholars, run Islamic schools, or even teach law. Some write articles or act as “experts” in media. Others are involved in human rights organisations, but they quietly block efforts to expose the regime. Some have ties to politicians and help shape who can get access to MPs or senators. It’s a very layered network—like an onion. You have to peel back a lot to get to the core.

ZB: One of my friends—she’s Iranian—told me she has a list of questions she asks when she meets other Iranians in Australia, to try to work out whether they might be regime-aligned or spies. Do you do something similar?

DT: I’ve been in Australia for over seven years, and yes, I can usually tell straight away if someone is pro-regime. You can see it in the language they use—their vocabulary gives them away. For instance, if someone talks about “occupation” or uses the word “genocide” in relation to Israel, that’s often a sign they’re anti-Israel. You don’t even need to ask directly; just let them speak for five minutes, and it becomes clear.

ZB: “Zionist” is another word they tend to use in that way.

DT: And the same goes for determining someone’s stance on the Iranian regime. If they’re openly anti-monarchy, that usually indicates they’re pro-regime—or at least sympathetic to the Islamic Republic. Because right now, the only viable alternative to the Islamic Republic is the return of the monarchy. So being anti-monarchy effectively puts you in the same camp as the regime.

ZB: Right. So, during the revolution, people didn’t fully realise what they were getting. They thought they were just getting rid of the Shah for something better—maybe socialism—but what they actually got was Islamism?

DT: Yes. The majority of people at the time were silent. Many didn’t even understand the difference between an Islamic republic and a socialist republic. A small number spoke out, but they were threatened and silenced. One of the earliest acts by the revolutionaries was burning down a cinema full of people—over 600 people were killed while watching a film. That level of intimidation silences dissent.

What happened in 1979 wasn’t a popular revolution—it was more like a coup, or a manipulated uprising. It wasn’t like the Russian or French revolutions. There were elements of revolt, but also strong international interference. The people didn’t really play an active, decisive role.

ZB: Do you think there were valid reasons for people not supporting the Shah?

DT: No, not really. I think people were simply too ignorant of the consequences. They had supported the Shah in the past—most notably in 1953, during what many in academia now call a coup, but which was actually legal. People supported the monarchy again in the 1940s, when Reza Shah stepped down and his son took over.

But by 1979, a new generation had grown up. They hadn’t experienced the hardships of previous decades—so they didn’t appreciate what they had. They assumed peace and prosperity were normal, and they didn’t realise what they stood to lose.

ZB: So, can you explain a little bit about why you’re a monarchist or a royalist, and why maybe secular liberal values or liberal democracy for Iran won’t necessarily work as well?

DT: Yes, sure. When you're talking about a society, there are different roles or power structures that exist within its fabric. Religion is one of them. In older civilisations like Iran, monarchy is another—political elites connected to the monarchy are deeply embedded within the society. In more recently established liberal democracies, academia plays a similar role.

Now, when you're facing a force like Islamism, which believes religious leaders must rule, you need a counterforce. But you can’t rip apart the fabric of the society to do that. In Iran, monarchy is the only existing force that has the historical and cultural weight to counterbalance Islamism—without sparking further conflict or civil war.

Unfortunately, secular liberal democracy doesn’t have enough power to face down Islamism in the way that's necessary. That’s why we see Islamist movements growing in liberal democracies—they take advantage of free speech and political pluralism until they’re strong enough to impose their own rules. And because democracy is based on majority rule, once Islamists become the majority, the whole system can fall.

ZB: You're scaring me, Daniel. It’s all very unsettling. But I agree. In the West, when we hear someone say they’re a monarchist, we often think, “That’s outdated—why not support democracy?” But I see your point. Secular liberalism doesn’t have the power to push back against political Islam. Maybe that’s even a reason why Australia should remain a constitutional monarchy.

DT: Yes. Legal experts can explain this better, but a monarch provides stability and continuity. Monarchies resist radical swings. In Australia, for instance, the Governor-General—appointed by the British monarch—has the power to dissolve Parliament. That’s a balancing mechanism. In Iran, monarchy could play that same role again.

In other countries, like the US, the Supreme Court plays that role. But even that body can become politicised. In constitutional monarchies like Australia, Japan, or even those in the Middle East—such as Jordan, Saudi Arabia, the UAE—monarchies have brought relative peace and prosperity. Meanwhile, republics in the Middle East are mostly in turmoil.

ZB: So we’re talking about monarchies like the UAE, Qatar, Kuwait, Jordan…

DT: Yes. Morocco, Oman, too. These are the relatively stable countries in the region. And they’re all monarchies.

ZB: They're the ones tourists can actually visit. That’s one more thing—I’d love to visit Iran one day. Inshallah. And I hope that you and other Iranians like you can one day return home—to a better Iran, a safer Iran.

DT: I hope so too.

ZB: There’s so much history and archaeology I want to see. I’ve read so much about it. But it’s just not feasible—especially as a young woman who’s outspoken online. Hopefully, one day.

DT: I hope that day comes.

ZB: One of the things that really radicalised me about the Iranian regime was during COVID—I remember seeing news that Iranian athletes, I think Olympic wrestlers, were executed. Beautiful young men, publicly hanged. I saw the images. And since then, I’ve seen many such images—of handsome, vibrant young people being killed. It’s horrific. But Western media doesn’t show this. People see images of Palestinians under bombardment, but not Iranians being executed. Are public executions still happening? Did you see them growing up?

DT: Yes. As a child, I saw public executions. In the city where I lived, there was a central square—very crowded—right in front of my father’s workplace. That’s where they would hang people. I remember seeing families crying, people collapsing in grief. It’s an image I can’t forget.

And yes, public hangings still happen. Just a few days ago, they executed a young man accused of being an Israeli spy. There was also a disabled man, in a wheelchair, executed on similar charges. In the past year alone, there have been over 500 executions.

ZB: Do they execute women as well?

DT: Yes, though it’s less common. One well-known case is Reyhaneh Jabbari. She was executed for defending herself against rape—her attacker was an intelligence officer. She was sentenced to death and hanged.

ZB: May she rest in peace.

DT: Yes. And there’s also the case of Navid Afkari—a wrestler, executed in 2020. Donald Trump even tweeted in support of him. His alleged crime was killing a security officer, but the only evidence was a confession extracted under torture. The story didn’t add up.

During the 2022 protests, more young people were executed. Majidreza Rahnavard is one name. Another is Mohsen Shekari—we held up his image during a protest in Sydney. His “crime” was setting fire to a rubbish bin. He was executed for “waging war against Allah.”

ZB: I recently tweeted about Majid Kavousifar and his nephew Hossein, who were publicly hanged in 2007. The photos are haunting—they’re smiling, waving at the crowd, nooses around their necks. People online said, “Yes, but they murdered a judge.” Do we even know that’s true? Can we trust any of the regime’s claims?

Tehran, 2007. Majid Kavousifar (28) and his nephew Hossein (24) moments before their public hanging by the barbaric Iranian regime. pic.twitter.com/J9GDA6hej8

— Ζoë (@zoecabina) June 15, 2025

DT: That’s exactly the issue. It’s the same as Navid Afkari’s case. These “confessions” are made under torture. The regime invents narratives, and people are executed without due process. There’s no right to a fair trial, no legal defence.

Majidreza was tortured before being hanged—some reports say they broke or burned his arm because he had the Lion and Sun emblem tattooed on it, the symbol of pre-revolutionary Iran. The charges are often symbolic—“waging war against God.” That’s what they call it.

And yes, I understand the concern around vigilante justice. If those young men did kill a judge, it’s not something we can endorse. But that judge—Moghadassi—was notorious for issuing death sentences for minor offences. Even if he was killed, the question remains: was there any due process? Was there any evidence? The regime’s courts can’t be trusted.

ZB: There’s no due process.

DT: Exactly. In Australia, if someone causes a death—say, in a drink-driving incident—there’s due process. They go to trial. They can defend themselves. Even in the most serious cases, there are legal protections. But in Iran, if someone defends themselves, or is accused by the regime, they may be executed on ideological grounds.

There are no safeguards—just ideological vengeance masquerading as justice.

ZB: Well, I truly hope the people of Iran have a better future. They deserve so much more than what they’ve endured. My heart breaks for them—and for the Israelis, too, who are under attack by the same regime. The Islamic Republic must go. It cannot keep inflicting this suffering and terror.

DT: I agree completely. I pray for the safety of all civilians—Iranians in Tehran, Israelis in Israel. This is not Iran’s war. The regime has dragged us into it. I hope this ends soon and with as little harm as possible. I’ve even heard Donald Trump has asked Tehran residents to evacuate. That terrifies me. It’s a city of millions—how can they evacuate? Where would they go?

This war has been imposed on us by the regime. I hope it ends quickly, and I hope the regime ends with it.

ZB: Yes, and thank you again. You are one of the bravest people I know. If listeners want to learn more or follow your work, what should they look for?

DT: I’m with the Mehre Iran Foundation. People can find us on Instagram, or email us at [email protected]. I’m also active on Instagram and on X. I’m always happy to share information and provide perspectives that don’t often get covered in the media or academia.

ZB: Wonderful. Thank you again, Danial.

DT: Thank you.