Education

Education’s Elephant in the Room

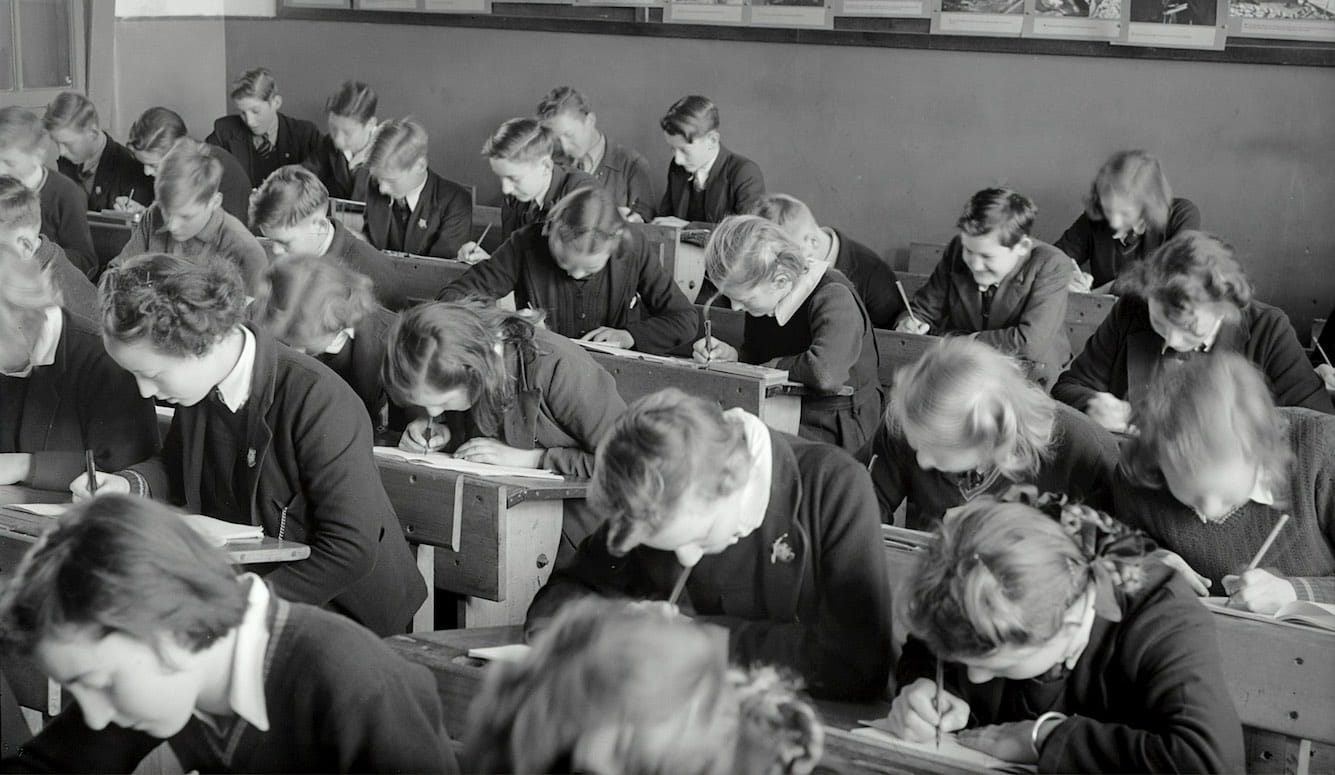

We devote a lot of resources to trying to equalise student outcomes, but under ideal learning conditions, individual differences in student achievement widen.

This essay is a lightly edited transcript of a speech that the author delivered at the Psychology Without Borders conference on 10 March 2025. The speech can be viewed here.

I have always been fascinated by human learning, but the cognitive psychology approach to studying learning did not appeal to me. I was not interested in laboratory studies on learning and memory. I was far more interested in the classroom. That is why I decided to study educational psychology in graduate school. Educational psychology is much more applied than cognitive psychology.

However, most educational psychologists share a common interest with cognitive psychologists in understanding how a change in conditions results in an average change in an outcome. Both groups pay little attention to individual differences. The cognitive psychologist generally sees individual differences as random “noise” or “error” that needs to be cancelled out by averaging scores in a group. Even under the carefully controlled environment of the laboratory, individual differences in learning remain. But that is not random “noise” to ignore, it is an important phenomenon to understand.

Educational psychologists also see individual differences in their work, but their reaction to them is different. Rather than ignoring them (as the cognitive psychologist does), most see individual differences as a failing of the education system—especially if struggling students don’t meet the standards set for them. In the United States, the dominant educational policy goal is to reduce achievement gaps between rich and poor, between states, and between individuals. We devote a lot of resources to trying to equalise student outcomes. However, when schools have a good curriculum and experienced teachers, individual differences in student achievement widen. Yes, struggling students do perform slightly better—but the most able students show greater gains. This is a classic example of the Matthew effect.

It is not just ideal learning conditions that fail to eradicate individual differences. Equalising learning conditions has the same effect. After the communist revolution, the Soviet education system was reformed to equalise school environments as much as possible throughout the Soviet Union. During the 1920s and early 1930s, educational achievement tests showed that some children were still learning more than others. So, in 1936, the USSR banned standardised testing altogether. It was much easier to ban the tests and hide individual differences than it was to actually eliminate them.

Equalising educational environments often magnifies individual differences in learning. I recently saw this firsthand when I observed the classroom teaching at the United States Army’s Future Soldier Preparatory Course. This is an educational program that is designed to help aspiring recruits pass a test needed to enlist in the army. This three-week course is the most equalised educational environment I have ever seen in my career. All the students wake up at the same time, eat the same meals, dress the same, and attend classes with the same excellent curriculum. They even have the same haircut. All of them are extremely motivated because they want to join the military, and they are paid for their time attending the course. The classrooms are completely free of distractions, such as cell phones. And with a drill sergeant in the room watching the students, there are zero behavioural problems or disruptions. Despite this ideal and equalised classroom environment, individual differences in learning speed and in mastery of the curriculum were not eliminated. If anything, they became more obvious than in a normal classroom. When everyone is treated as similarly as possible, the individual differences that remain become harder to ignore.

No educational program or policy has ever eliminated individual differences in learning outcomes, and these examples show that many policies actually increase the magnitude of individual differences. I do not think that most educational psychologists and the educational establishment in the United States fully grasp the implications of these individual differences. It is an elephant in the room. What causes these differences? Why do some people learn more, learn faster, and retain more information than their peers? Like any human behaviour, there is not just one cause. But—by far—the most important cause of individual differences in learning outcomes is intelligence.

One of the most consistent findings in psychology is that intelligence—as measured by IQ—is the best predictor of educational outcomes. People with higher IQs earn higher grades, score better on academic achievement tests, and go on to achieve higher levels of education. After IQ stabilises between the ages of seven and ten, it predicts educational outcomes better than any other variable. Depending on methodological characteristics of the studies, IQ and educational outcomes have a correlation between .40 and .80. No other variable comes close to having a relationship this strong with educational outcomes.

Teachers and schools matter, but they cannot eliminate individual differences among students.

In the United States, we should not be surprised that individual differences matter so much more than the educational environment. In 1966, the federal government produced the Coleman Report, which found that differences among schools had a weak relationship with differences in student learning outcomes. More recent research indicates that in industrialised nations, about ninety percent of differences in learning outcomes are associated with individual differences among students. This means that only about ten percent of differences in learning outcomes are related to school- and classroom-level characteristics. Teachers and schools matter, but they cannot eliminate individual differences among students; no teacher—no matter how dedicated and well-trained—can turn their struggling students into gifted overachievers. There just isn’t enough shared variance between classroom-level variables and individual student outcomes for that to be possible.

The education system has found different ways to deal with the elephant in the room. One strategy has been ignorance. One of my students and I surveyed a sample that included 200 American teachers to learn about their knowledge and opinions about intelligence. The results showed that teachers sometimes had an appalling lack of understanding about intelligence. Over 85 percent believed that it was too simplistic to measure someone’s intelligence with just one score, like an IQ. Almost 85 percent endorsed Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences. Almost forty percent thought that “street smarts” were more important for life success than intelligence. All of these beliefs are completely incorrect, yet large numbers of teachers—sometimes the majority—hold them. In contrast, only a third thought that students who perform better on intelligence tests would also perform better in school.

This is as if engineers had basic misunderstandings about the laws of physics. Engineering is one form of applied physics, and so an engineer who does not understand physics is going to be bad at their job. Bridges would fail, and buildings would collapse. Likewise, teaching is a form of applied psychology. A teacher who does not understand human learning and intelligence is not going to be successful. Students are going to learn less, and teaching is going to be less effective. Yet, educators (and those who train teachers) seem unconcerned about this.

How could teachers—who see intelligence differences every day in their classrooms—be so badly informed? A major reason is that they were never exposed to accurate information in their training. Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences—despite having little support from psychologists—is widely taught in American teacher training programs. My wife was a middle school drama teacher, and while we were dating, she told me that she learned Gardner’s theory in her teacher training program and thought it was true. She had no reason to question this received wisdom because the theory sounded good, and her education professors believed it. She knows better now, but a teacher shouldn’t have to marry a psychologist in order to learn that Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences is wrong.

Sometimes, teacher training programs even work to keep information about intelligence and IQ from their students. When I was a psychology professor, the faculty at my university’s education program heard that I had published articles on gifted education and reached out to me to ask if I would be interested in teaching a course on giftedness. I met with the dean, and told her that I was very interested, and that the course would be based on intelligence research and IQ. Later, I was told that the dean did not want me teaching in their program. When my colleague in the education program asked why, the dean told her, “We don’t teach IQ in our program.”

Misinformation and ignorance, though, do not fully explain the results of the survey. For example, only 42 percent of teachers agreed with the statement that, “A student with high grades in one school subject tends to do well in others.” Forty-eight percent of teachers did not agree with that statement, and ten percent were unsure or neutral. I am flabbergasted that fewer than half of teachers could notice this basic aspect of their day-to-day job. How does a teacher not see that students who struggle in one area tend to struggle in others, or that the honours students in one subject tend to also be honours students in others? These tendencies aren’t ironclad, but they are consistent enough that they should be easily noticeable in everyday life.

That’s why I think another strategy for dealing with the elephant in the room has been to dismiss individual differences and to minimise or deny any connection that intelligence has with educational outcomes. This is how 73 percent of teachers can agree with the statement that “Some people are just smarter than others,” but then only a third acknowledge the connection between higher IQ and better academic performance.

In educational policy, we see schools acknowledging intelligence but denying its importance when they offer ineffective gifted programs. My eight-year-old daughter has qualified for the gifted program in the local school district. Each Wednesday afternoon, she boards a bus to attend an enrichment program at another school. The school district acknowledges that individual differences exist by labelling some children as “gifted” and others as not. But a program that lasts only half of a day per week is not a program that someone would design if they understood the consequences of individual differences in intelligence within an educational system. My daughter is bright every day, not just on Wednesday afternoons. Why doesn’t she attend a gifted program every day?

Another unacknowledged consequence of individual differences in intelligence is seen in how schools do not accommodate students’ varying learning speeds. In the United States, almost every student moves through the school system at the rate of one grade per year, from kindergarten through 12th grade. This lockstep policy works for the average student, but it is not effective for students with significantly higher or lower intellectual ability. Struggling students need more than thirteen years to master the curriculum; very bright students need less. Most school systems in the United States do not adjust the rate of grade advancement to reflect this reality. Instead, almost every student advances at one grade per year—regardless of their level of mastery of the curriculum.

This is how the system produces high-school students who are barely literate. In the United States, almost ten percent of 12th graders have lower reading achievement than the average 4th grader. These students would profit from extra time to complete the K-12 curriculum, especially if they are given tutoring and other special resources to help them.

On the other side of the distribution, by the end of the 11th grade, up to a quarter of high-school students are considered “college ready.” These students could skip their final year of high school and start college immediately. Yet, this rarely happens. Indeed, grade skipping at any stage in the American primary or secondary system is rare. In a given year, only about one in 400 American school children skip a grade. Many more could, but parents rarely make this request, and schools rarely make parents aware of this option or that the child qualifies for a grade skip.

In fact, sometimes school personnel actively resist grade skipping, and the objections can be ridiculous. A colleague of mine participated in a grade-skipping conference for a middle schooler. Most of the teachers were positive about the idea, but the school’s Texas history teacher objected. She was disappointed that a child would skip 7th grade and miss taking a Texas history class, and she resisted the grade skip. Never mind that there are 49 other states that do not teach Texas history; because a student might miss out on the class centred on her passion, this teacher tried to halt his grade skip.

After my brother skipped 8th grade, his 9th grade English teacher resented having a younger student in the class and gave my brother lower grades for work that was better than that of his classmates. When my parents discussed this with the teacher, he said that my brother was not as smart as they believed and that the problem was that my brother had skipped a grade. Yet, my brother’s objective test scores were very high and showed that he was outperforming his older classmates. So, one petty teacher tried to punish my brother for being accelerated just because the teacher didn’t like grade skipping.

An unexpected obstacle to grade skipping in the United States is the bizarre American obsession with high-school social life. Towards the end of his 1st grade year, my wife and I suggested that our son skip the 2nd grade. The principal said, “But won’t he feel bad when he’s in high school and he’s a year younger than his classmates? They will be driving and dating, and he won’t be able to do that for another year.” This principal was willing to sacrifice my son’s immediate academic needs to her worries about what his social life would be like a decade later. In response, my wife and I gently reminded her that our son’s social development was our responsibility and that her responsibility was meeting his educational needs.

A similar objection was raised when I was presenting on the benefits of grade-skipping at a state gifted-education conference. The president of the state gifted-education association interrupted my presentation and stated in front of the entire audience that any benefits of a grade skip have to be weighed against the social cost of being a year younger than classmates in high school. She said that boys may have difficulty finding a date to go to prom with if they’re a year younger than the girls in their class and that being a year younger would make it harder to qualify for sports teams. Keep in mind, this was the president of the state gifted education association. She was supposed to be an advocate for bright children, and yet she was more worried about a child’s sports prospects or dating life than meeting their educational needs. If anyone should know better, it is her.

In fact, there is no evidence that grade skipping creates any harms—academically, socially, or otherwise—for children. I believe that a major reason school personnel fight grade skipping is that they do not grasp that differences in intelligence will have consequences for learning speed. They also do not understand the magnitude of the differences in learning speed. Most educators are shocked when I tell them that up to a quarter of American students could skip their final year of high school. A portion of those students, perhaps five or ten percent of the entire student population, could skip two or more grades over the course of their educational career.

Some well-meaning educators suggest that a good teacher should instead accommodate individual differences by customising lesson plans for children who are at different levels of academic achievement. This is very naïve thinking. The differences among students’ educational achievement start early and increase as children grow. By 5th grade, the average American classroom has children whose achievement in mathematics and reading ranges from the 2nd grade level to the 8th grade level or higher. It is simply impossible for a single teacher to prepare lessons in every subject that allow every student to learn new information. Some sort of ability grouping, in which students at similar levels of achievement are taught together, is necessary. This happens, for example, in Germany, where the education system sorts students into different types of schools, with some students being steered towards a vocational track and others into a college preparatory curriculum. But even ability grouping has its limits. At some point, some children will learn too quickly or too slowly compared to their peers, and the bright children will need to be accelerated, and the struggling students will need additional supports and time to master the curriculum.

What causes these individual differences in intelligence and achievement that educators are so determined to deny, downplay, or ignore? The major causes can’t be anything originating in the school or the classroom, because that only explains about ten percent of the variance in individual education outcomes. The major causes of these differences must be at the student level.

This is where educators get really nervous, because the major cause of individual differences in intelligence seems to be genetics. The heritability of IQ varies, but in wealthy, industrialised countries, it approaches .80 in adults, which indicates that eighty percent of individual differences in IQ are associated with individual genetic differences. In young children, heritability of IQ is lower, but it hits .50 at about age ten and continues to increase into adulthood before levelling off. Heritability of educational achievement varies by topic—it is higher in word reading and arithmetic than in spelling, for example. But for most ages and most school subjects, heritability for academic achievement in children is even greater than heritability of IQ.

Genes matter more for determining individual differences in school performance than they do for IQ.

At first glance, this is puzzling. Academic achievement depends on going to school and learning the information that books and teachers impart. Most content on intelligence tests, on the other hand, is not the information that is explicitly taught in school. It seems that environment should matter more for explaining educational achievement differences than for IQ. But it does not. Genes matter more for determining individual differences in school performance than they do for IQ.

Recent research has shown why. Good academic performance is more than the consequence of high intelligence. Performing well in school also requires non-cognitive characteristics, including motivation, interest in academics, emotional stability, and more. The heritability of educational achievement is higher because there are more genes influencing the cognitive and non-cognitive aspects of educational attainment than there are for the cognitive aspects alone.

In retrospect, educational psychologists should not be surprised. Scientists have known for decades that the best predictions of college grades come from combining standardised test scores and high-school grades. High-school grades capture the non-cognitive influences on educational performance that the tests miss. These include punctuality, the ability to follow directions and turn assignments in on time, not being disruptive in class, and a willingness to work hard and study. These behaviours are themselves genetically influenced, and they are partially caused by a different (but overlapping) set of genes from those that influence intelligence.

Turning to the views of teachers, though, we find widespread misinformation. In a British survey, only 29 percent of teachers thought that genes were one of the top three factors affecting student achievement. In other words, the scientific research shows that genes are usually more important than every environmental cause combined, and yet most teachers don’t even believe that genes rank in the top three causes of educational achievement.

The dominant view in that survey—which is also common among American educators—is that socioeconomic status and family home life are the most important influences on how a child performs in school. To be fair, this is a reasonable belief. Children from more stable homes and wealthier families do perform better in school. The problem with attributing this correlation to a causal relationship by saying that the better home environment causes better school performance is that most children are raised by one or both biological parents. This means that the genetic and environmental influences of the parents on a child are confounded. Therefore, the correlation between parental behaviours and child outcomes does not tell us whether that relationship is caused by the environment or not. Indeed, it cannot say whether that relationship is caused by genes, either.

A rather easy way to tease apart the relative effects of parental genes and parental environments is to look at the results of adoption studies. When children are adopted by people to whom they are not related, any similarities they share with their adoptive parents must be environmental because the children and parents do not share any genes. The research shows that these adopted children do, indeed, have an increased level of educational attainment. They attend college at higher rates than children born in similar circumstances but raised by their biological parents, for example. Adopted children also experience an IQ boost of about three points in wealthy countries. So, environment definitely matters.

But adopted children’s IQs nonetheless still more closely resemble the IQs of their biological parents, and adopted children’s educational attainment lags behind the performance of the biological children of their adoptive parents. These findings cannot be explained through environmental mechanisms. So, genes definitely matter as well. Both genes and environment contribute to individual differences in educational outcomes. When studies are designed so that scientists can compare the relative contributions of genetics and environment, the genetic influence is more powerful than the environmental influence, starting at about age ten.

Adoption is not the only way we can untangle the influence of genes and environment. In fact, adoption studies are one type of research design that is called “genetically sensitive designs,” which are intended to control for genetic confounds. Studies that use random assignment are another type of genetically sensitive design. When we randomly assign a large sample of students to education programs, the groups start the study equalised on all variables, including sex, socioeconomic status, motivation, genetic propensity towards learning, and any other variables. Even variables that we do not think are relevant are equalised. After random assignment, any differences in academic outcomes between groups must be due to the impact of the different educational programs they experience.

Without random assignment, groups of students enrolled in different educational programs are not equivalent. When that occurs, we cannot say that average differences between the students are caused by an effective educational program. Of course, we often cannot randomly assign people to educational programs. For example, a tutoring program may only be available to struggling students. In this example, we cannot say that the tutoring program causes a faster increase in test scores than what untutored children experience. There are pre-existing differences between children in the tutoring program and children who are not in the tutoring program, and those differences may be the cause of any changes in educational outcomes that they experience. Some of those differences may be genetic and some may be environmental. A research design that merely compares non-equivalent groups of students in different programs cannot state what causes differences in educational outcomes.

This is also true for programs that students (or their parents) choose. For decades, there has been research showing that children learning to play an instrument have higher achievement in school than children who do not learn to play an instrument. Of course, a lot of educators jumped to the conclusion that music instruction causes better educational outcomes. But years later, research showed that the findings were likely due to pre-existing differences between children whose parents make them learn an instrument and children whose parents do not. We do not know which pre-existing differences are causal. Maybe children learning an instrument come from wealthier homes. Maybe their families are better at instilling responsibility and goal-setting. Maybe there are genetic differences. But the result is that individual differences matter, and without random assignment to control for them, we cannot understand how effective environmental interventions are.

Ironically, the experimental design of comparing average group outcomes after random assignment to an educational program is an import from cognitive psychology. And comparing averages for groups while cancelling out the “noise” of individual differences was the sort of approach that I found uninteresting when I was a college student. It took years of focusing on individual differences for me to understand the value of experimental designs and average outcomes. I now believe that it is because individual differences are so pervasive and powerful that we often need to control for them so that we can understand whether our educational programs are effective or not.

But the educational world often resists random assignment. For example, I once conducted a study in which I analysed archival data on academic acceleration, which is a catch-all term for any educational intervention that causes a child to finish their schooling early. In the study, my coauthor and I compared the adult incomes of high-IQ children who had experienced acceleration with other high-IQ children who had not been accelerated during their education. The accelerated males in the study had higher incomes as adults, but for females there were no differences. At the end of the manuscript, we recommended that researchers conduct a follow-up study in which eligible children are randomly assigned to skip a grade or remain in their current grade with their age peers. Four out of the five peer reviewers of the manuscript objected to randomly assigning children to being grade skipped, claiming it was unethical. Some of the comments seemed to indicate that they were even outraged at the suggestion.

One reviewer stated, “how is it even remotely ethical or moral to engage in such an experiment? It would be wholly inappropriate to randomize living people to such an intervention, with or without their consent.” Another said, “I have to express huge ethical concerns on the suggested experimental design! [When] you know about positive effects of grade skipping, you can’t restrict access for randomly chosen subjects who would lack such [a] beneficial opportunity!”

Of course it is ethical to randomly assign people to an intervention. True experiments with random assignment to conditions is the most basic design to be able to identify cause-and-effect relationships. Every student in psychology and many other social sciences learns this, and scientists have conducted randomised trials on humans for treatments far more serious than grade skipping. Every day, medical researchers randomly assign patients to cancer treatments or to receive an experimental drug or a placebo. These medical studies have far more serious consequences for research participants than academic acceleration does. But there would never be four out of five peer reviewers at a medical journal objecting to a randomised control trial. In education, there was.

Eventually, I got the study published, including the recommendation. But to do so, my coauthor and I had to add over 350 words to the manuscript to explain that randomly assigning people to treatments is considered ethical and that it is a methodology with widespread acceptance. We also pointed out that without a randomised control trial, educators did not know the full extent of the benefits of grade skipping. As a result, advocating for a treatment without being able to accurately weigh its costs and benefits could be considered unethical. From this perspective, there is an ethical imperative to conduct a study that randomly assigns eligible children to grade skip or remain in their regular grade. But clearly such a perspective was not a natural one for four out of five education scholars reviewing my article.

Educators may sometimes resist random assignment because they do not want to admit how important individual differences are. After all, if humans were basically interchangeable and individual differences did not have a powerful effect on outcomes, then randomised control trials would be unnecessary. Under those conditions, we could accurately evaluate educational programs just by making direct comparisons of groups of students. But that is not the universe we live in.

Some educators may also be uncomfortable grappling with individual differences. At the last education conference I attended before the pandemic, I presented on the importance of genetic differences in education. The audience’s reception was very heated, and many people were outraged when I suggested that there might be genetic differences between gifted and non-gifted students, or rich and poor students. I was worried that people would rush me and that I might be in danger. And this was not some rabble listening to my talk; the audience included university professors, education policymakers, teachers, and others. Later, on social media, I saw comments deriding me for suggesting that genetic differences could exist between socioeconomic groups—even though there are many studies showing this. In fact, recent research has shown that genetically influenced socioeconomic differences have existed in some societies for hundreds of years.

However, I want to add an important caveat. Most of this research on individual differences in education has occurred in wealthy countries. In these countries, there is a baseline favourable environment that almost every child experiences. In these countries, every child is required to attend school, teachers are trained and well-paid, school buildings are not dilapidated, and books and other materials are plentiful. This is an educational environment that allows most students to flourish. But there are many countries in the world where these conditions do not exist. A recent study of schools in Africa showed that a third of classrooms randomly visited by researchers had an absent teacher. Even when teachers do show up to work, only about half of the instruction time is spent teaching. To make matters worse, over a third of adolescents worldwide do not attend school at all. I don’t care how much genetic potential a person has; if they are in an environment like that, they are unlikely to thrive in their education.

So, with our understanding of the importance of individual differences, what should we, as scientists, do?

First, we should be unafraid to talk openly about the importance of individual differences. That includes conducting research on the causes and consequences of these individual differences in the education system. One excellent study on this in an international context was the Study of Latin American Intelligence conducted in six Latin American countries. Carmen Flores-Mendoza and her colleagues gave intelligence tests to children and identified demographic, home, and educational variables that correlated with IQ scores. The focus on the international context, the community context, and the individual is rare in the same study. Additionally, data and a perspective from Latin America revealed important insights that we do not get from most research on intelligence, which is dominated by studies conducted in Europe and North America.

A challenge to this research is that intelligence tests are often expensive and time-consuming to administer. And many countries do not have well designed intelligence tests normed on their populations. My colleagues and I are trying to address these issues through a few tests I am developing. One is the Reasoning and Intelligence Online Test, or RIOT, which is an affordable online intelligence test for adults that produces a score profile that measures intelligence and other cognitive abilities. We are launching the RIOT in the next several weeks in the United States, but we hope to have it normed in other countries and translated into other languages before long. I have also created the Warne Intercultural Test of Intelligence, or WITI, which is designed to be an inexpensive and culturally universal measure of intelligence in children. I am in the process of applying for funding for a trial study. I hope that it becomes an option for measuring intelligence in economically developing nations.

Second, we should support policies that give every child an educational environment in which their individual differences can become apparent. Worldwide, too many children do not have this opportunity. An appreciation for individual differences does not mean that we ignore environment or educational programs. Instead, it prompts many researchers to support educational reforms that offer more opportunities for all children. Yes, this will often increase variance and magnify the individual differences among students, but it also increases the mean and helps all children achieve more.

Third, once the basic educational environment is adequate, we should advocate for programs that are tailored towards students’ individual differences. Struggling students should get extra help and tutoring, while gifted students should receive advanced classes and opportunities for acceleration. We should encourage educators and policy makers to accept, and perhaps even embrace, individual differences.

Individual differences existed in the education system long before standardised tests could objectively measure them. They will always continue to exist because these differences are partially genetic in origin, and they manifest themselves when the educational environment meets basic standards. For decades, politicians and educators have tried to eradicate these differences, but they have always failed because they can’t equalise students genetically. As psychologist Arthur Jensen stated over fifty years ago, “A philosophy of equalization, however laudable its ideals, cannot work if it is based on false premises, and no amount of propaganda can make it appear to work. Its failures will be forced upon everyone.”