Art and Culture

It’s No Longer 1937...

Disney’s awful new Snow White adaptation fails to recreate or even understand the story it is trying to tell.

I.

The Disney company’s 2025 live-action version of Snow White is just as terrible as nearly everyone says it is. The film has attained an abysmal score of 1.7 on IMDb from 360k ratings and 2.2k reviews (although the site warns, “Our rating mechanism has detected unusual voting activity on this title.”) At Rotten Tomatoes, meanwhile, the film has racked up a more generous audience score of 71 percent and a critics’ score of forty percent (although many of the positive reviews are of the “not quite as terrible as you have heard” variety). The upshot has been an eye-wateringly expensive box-office flop as well as a critical disaster. Disney’s animated 1937 adaptation of the Grimm brothers’ fairy tale—the first animated feature film ever made—remains a beloved classic (7.1 on IMDb nearly ninety years after it was released, and no unusual voting activity flagged). So how did Disney manage to take a bankable property and produce something this bad?

The new Snow White is bad because, while its 24-year-old lead, Rachel Zegler, is a decent singer, she can’t act very well and she’s been woefully miscast—probably because she is half-Latina and thus qualified the movie for post-#OscarsSoWhite “representation and inclusion” points. (With a Peruvian mother, I’m half-Latina myself, so why didn’t someone ask me to play Snow White?) In Disney’s animated 1937 version (titled Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs), our heroine was a sweet and cheery innocent, but Zegler’s character has been rewritten as a Mary Sue girlboss who shows off what a smartypants she is by reciting all the dwarfs’ names in reverse alphabetical order upon being introduced to them. And instead of cleaning their house in return for their hospitality, she makes them do their own cleanup. It’s “Whistle While You Work” for thee, but not for me. If you found yourself hoping that this obnoxious know-it-all would remain dead after biting into the poisoned apple, you were not alone.

The new Snow White is bad because the seven dwarfs are crudely rendered CGI motion-capture creations. They look less like the Doc, Grumpy, and co. we fondly remember than what one critic described as “garden gnomes.” Unlike the 1937 cartoon originals with their seven distinctive comic personalities, the new uncanny-valley dwarfs are difficult to tell apart, except for Dopey, who looks like Alfred E. Neuman in a medieval hat. (The new Snow White, by the way, won’t even let Dopey be Dopey; he has to have a lugubrious back story in which he doesn’t speak because he’s “afraid.”)

The “gee thanks” for this visual and conceptual travesty goes to Peter Dinklage, who decreed that simply casting a Latina was not satisfactory. “You’re progressive in one way,” he griped during an appearance on the WTF podcast, “but then you’re still making that fucking backward story about seven dwarfs living in a cave together? What the fuck are you doing, man? Have I done nothing to advance the cause from my soapbox? I guess I’m not loud enough.” Panicky Disney executives immediately issued a statement to the Hollywood Reporter, in which they reassured everyone, “To avoid reinforcing stereotypes from the original animated film, we are taking a different approach with these seven characters and have been consulting with members of the dwarfism community.”

For a while, Disney seemed to be toying with using full-size actors instead of dwarfs—until the Daily Mail published production photos leaked from the British set showing seven costumed adults of varying ethnicities and sexes accompanying a Zegler stand-in across a hilly landscape. “Snow White and the Seven... Politically Correct Companions?” the headline jeered. The social-media ridicule that followed was so intense that Disney quickly sidelined the Companions (who remain in the movie but mostly as fifth wheels with nonspeaking parts) in favour of the CGI grotesques we must now endure. Even the word “dwarfs” is pointedly avoided (the new nomenclature is “magical beings”). The “dwarfism community,” meanwhile, complained that Dinklage, who became a superstar in Game of Thrones, had effectively robbed them of one of their few available job opportunities: “To erase that and use CGI, like we’re mythical creatures or people that could be made on computers, it’s disregarding us in general,” an actor with dwarfism told Sky News.

And the new Snow White is bad because it gets rid of the handsome prince. Why? At Disney’s D23 Expo in September 2022, Zegler bragged that she and her fellow cast members were bringing a “modern edge” to the story. Asked by Variety to elaborate, Zegler enthused: “I just mean that it’s no longer 1937. ... [Snow White] is not going to be saved by the prince, and she’s not going to be dreaming about true love; she’s going to be dreaming about becoming the leader she knows she can be.” Well, OK—but try telling that to the 99 percent double-X chromosome Hallmark Christmas-movie-binge demographic, for whom “Someday My Prince Will Come” is the whole point. Instead, the new hear-me-roar Snow White offers Andrew Burnap playing a proletarian bandit-radical named Jonathan who steals potatoes from the royal larder (is he also a vegan?) and sings warmed-over Bertolt Brecht:

Let me break you the news

The odds can’t be beaten

And a man’s gotta choose

Will he eat or get eaten?

Isn’t that romantic? Unsurprisingly, the new Snow White does not wind up with the wedding she enjoys at the end of the Grimm brothers’ original fairy tale. Nor does Jonathan (unlike the prince in the 1937 cartoon version) lift Snow White on to his horse after his kiss resuscitates her from suspended animation. It’s barely a kiss at all in the new film, since smooching an unconscious woman violates #MeToo’s “enthusiastic consent” standard, even when said smooch is intended to save the smoochee from eternal hibernation. By the time the film closes, Snow White and Jonathan seem to have lost interest in each other entirely, so instead, we get an all-cast dance-party to celebrate Snow White’s ascension as “leader” after the wicked queen (Gal Gadot) dissolves into thin air. The cute faux-manuscript page (borrowed from the 1937 version) that winds up the finale depicts a solitary Snow White on the throne by herself with no spouse or offspring to be seen. Isn’t a crucial part of being a monarch establishing a bloodline?

The girlboss heroine, the anonymous CGI dwarfs, and the substitution of romance with ambition are all bad and depressing things, but they are not the worst thing about the new film. The worst thing is its failure to recreate or even understand the story it is trying to tell or the power that story has exerted over generations of readers and re-tellers. Snow White cost US$270 million, making it one of the most expensive movies Disney has ever produced—a fortune in shoots and re-shoots as the project floundered amid delays, antagonistic media reports, and Zegler’s running social-media commentary about feminism, Trump, the Americans who voted for Trump, and Israel’s Gaza war. Disney selected Marc Webb to helm the project, a top-rated fantasy director who had previously made The Amazing Spider-Man (2012) and its sequel. No fewer than seven writers pitched in on the screenplay, but only Erin Cressida Wilson (The Girl on the Train, 2016) received a screen credit. (Greta Gerwig is reported to have been called in on a script-rescue mission mid-shoot, and since she has a track record of turning preadolescent girlhood favourites like Little Women and Barbie dolls into instruments of feminist consciousness-raising, it is possible that she tanked the new Snow White single-handedly.)

But for all the money, talent, and time (the project was green-lit in 2016) involved, the end result is a feeble didactic parable of leftist ideology. As the film begins, a voice-over channelling Karl Marx and Woody Guthrie intones: “As she grew, the king and queen [Snow White’s parents] taught Snow White that the bounty of the land belonged to all who tended it.” Snow White and her parents then sing a song titled “Good Things Grow” (I half-expected a brand-new Soviet tractor to materialise at this point). As for Snow White herself, she’s not allowed to be “the fairest of them all” in the sense of the most beautiful, as the brothers Grimm wrote in their fairy tale’s most famous line (“die Schönste im ganzen Land” in their German), but in the pedestrian sense your mother used when she said, ‘‘Life isn‘t fair” after you complained that your fifth-grade teacher was picking on you.

Everything about the new Snow White bespeaks a pervasive failure of imagination. The CGI effects cannot match the prodigious and meticulous visual creativity of the 1937 animation. In that cartoon, Snow White falls asleep in the forest after she runs from the wicked queen’s burly assassin, and awakens to find dozens of delightfully hand-animated woodland creatures peering curiously at her—squirrels, chipmunks, rabbits, raccoons, skunks, a doe-and-fawn duo, a comic turtle, and singing birds galore. Compare that famous scene to the paltry animal offerings on display in the remake: a couple of squirrels, a bird or two, and just one lousy deer, none of whom have any personality or charm.

The ticky-tack and garishly hued costumes (compare the blues of Snow White’s 1937 and 2025 bodices) look as though they were ordered from Amazon. Jonathan and his bandit sidekicks look as though they were told to show up on the set in their everyday pants and hoodies and then each issued a pair of medieval boots. The songs, by Benj Pasek and Justin Paul (La La Land, 2016), are uniformly forgettable, while the 1937 tunes by Frank Churchill and Larry Morey are still sung and hummed to this day (covers of the Churchill-Morey “Whistle While You Work” and “Heigh-Ho” from the original are the only memorable musical pieces in the entire remake). Even the continuity is poor: Zegler’s makeup looks completely different from scene to scene. This etiolated and banal landscape is enough to make you wonder what happened to Western culture during the 88 years between 1937 and 2025.

II.

The story of Snow White that the brothers Grimm claimed to have retold in their 19th-century collections of German folk tales is a repository of at least three powerful archetypal elements. First, the deadly jealousy of a mother watching her own beauty fade while her daughter blooms (in the Grimms’ original version of the tale, published in 1812, the wicked queen is Snow White’s biological mother, not her stepmother). Second, the protagonist’s coming-of-age journey into the magical forest. Third, the resurrection as snow-white winter melts into fecund spring with the arrival of the prince-bridegroom.

In some ways, the story resembles the Greek myth of the nymph Chione (her name apparently connected to the word “chiōn [χιών],” which is ancient Greek for “snow”), as narrated in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. According to Ovid, Chione was so beautiful that, by the age of fourteen, she had already attracted a thousand suitors. The god Mercury, struck by lust, caused her to fall into a deep sleep, during which he raped her. Later that day, she was raped again by the god Apollo, who gained access to her chamber by disguising herself as an old woman. She then bore twins, one by each god, but she made the mistake of boasting about her beauty in front of the goddess Diana. In a fit of jealousy, Diana killed Chione by shooting an arrow into her tongue.

Although it is unlikely that the myth of Chione was a direct source of the Grimm fairy tale, there are tantalising parallels in the deathlike sleep, the murderous female rival, the crone disguise used to gain the victim’s confidence (in the Grimm tale, the queen fits herself out as an old peddler-woman). But the most powerful shared theme of all is that of the central character herself: the lovely virgin girl just entering nubility (early teens in traditional cultures, because that is when girls become ready for marriage), who can wield power over men for good or ill by the sheer force of her innocence, her virtue, and her physical radiance.

In her 1986 book, Women in Greek Myth, the classicist Mary Lefkowitz discusses the parthenoi (maidens) who populate ancient Greek storytelling. As Lefkowitz points out, these young women either lose their autonomy by becoming wives or mothers, or they die like Antigone, and Iphigenia—or Chione. But during their brief maidenhood they become memorable. In the Odyssey, the young princess Nausicaa cows the worldly and war-hardened Odysseus into gentleness and gentlemanliness when he washes up shipwrecked and naked on the shore of her father’s realm. “[M]ay the gods give you what your heart longs for, a husband and home,” Odysseus tells her.

In the Grimms’ fairy tale, Snow White is only seven years old when her beauty starts to outshine that of the queen, as the mirror on the wall informs us. She is obviously a few years older than that—of wedding age—when she flees into the forest to be befriended by the dwarfs and found by the prince, but the point of the story (and the point of many of the Grimms’ tales) is that her bewitching youth is more potent than all of the queen’s magic. She is “Little Snow-White” (Schneewittchen in the Grimms’ German). She is kind and virtuous, but like Chione, she is not perfect: her flaw is a weakness for pretty things, which leads her to ignore the dwarfs’ warning that she not let anyone into the house while they are gone. In the Grimms’ story, the queen as peddler-woman tempts Snow White three times on three different days. First, she offers Snow White a set of bodice laces so tight that they stop her breathing, then a comb for her hair that poisons her, and finally, the lethal apple. The dwarfs come home and are able to release her from the bodice-laces and the comb so as to save her life, but they cannot find the piece of apple lodged in her throat.

The brothers Grimm, Jacob and Wilhelm, revised their famous collection of tales several times between their first edition in 1812 and what is regarded as their definitive edition in 1857. Some scholars have argued that they simply invented the Snow White story, borrowing thematic elements from the tales of Cinderella, Hansel and Gretel, and Sleeping Beauty that also involve beautiful maidens, jealous family, and young children in the forest. The brothers maintained, however, that they had collected all of their folktales, including Snow White, from oral informants, and that these stories had been handed down in Germany for generations and mutated over time.

Many of the Grimms’ stories are so bloody in content and cruel in consequences that they feel authentic. In the Grimms’ Cinderella story, for example, the stepsisters hack off parts of their feet as they try to fit themselves into Cinderella’s slipper. These tales reflect the harsh and precarious world in which nearly everyone in the West lived until the end of World War II, where the fallout from even the smallest mishap or mistake could be humiliation, penury, hunger, and death. The brothers Grimm knew that well. Their father, a well-off district magistrate in the city of Steinau, had died of pneumonia in 1796 when Jacob was eleven and Wilhelm was ten, and the family was plunged into abject poverty. Miraculously, both brothers managed to get through university and carve out academic careers dedicated to the German language and its literature.

The Grimms’ Snow White (I’m following the 1857 version) is so violent and remorseless that it is hard for people nowadays to believe that it was ever intended for children. When the wicked queen orders the huntsman to take Snow White into the woods and stab her in the heart, she tells him to bring back Snow White’s lungs and liver as proof. Moved by pity, the huntsman spares the young girl and kills a wild boar so as to pass off its organs as hers. “The cook had to boil them with salt, and the wicked woman ate them,” the Grimms recount. The queen’s punishment for her evil deeds is even more sadistic, and it takes place at Snow White’s wedding: “Then they put a pair of iron shoes into burning coals. They were brought forth with tongs and placed before her. She was forced to step into the red-hot shoes and dance until she fell down dead.”

And yet, when I read those words myself at the age of eight or nine, in an unexpurgated edition of the tales that an aunt had sent me and my sisters, I got a thrill of satisfaction. Justice had been done. In my child’s imagination, only the most painful and prolonged forms of retribution struck me as condign, and I didn’t feel the slightest bit sorry for the evil queen or care what the Supreme Court might have thought of her cruel and unusual punishment. As the psychologist Bruno Bettelheim writes in The Uses of Enchantment (1976):

Since the fairy tale promises the type of triumph the child wishes for, it is psychologically convincing as no “realistic” tale can be. And because it pledges that the kingdom will be his, the child is willing to believe the rest of what the fairy story teaches: that one must leave home to find one’s kingdom; that it cannot be gained immediately; that risks must be taken, trials submitted to; that it cannot be done all by oneself, but that one needs helpers; and that to secure their aid, one must meet some of their demands. Just because the ultimate promise coincides with the child’s wishes for revenge and a glorious existence, the fairy tale enriches the child’s fantasy beyond compare.

III.

Even during the 1930s, however, this sort of savagery was too much for most people, and Walt Disney softened his adaptation of the story considerably. The liver and lungs were replaced by the queen’s demand that the huntsman simply bring back Snow White’s heart in a box (and it’s an organ that we in the audience never see). Disney also eliminated the queen’s first two attempts to murder Snow White with deadly objects, keeping only the poisoned apple. And the queen herself is killed by tumbling off a cliff instead of dancing to her demise in the red-hot shoes.

In the Grimms’ tale, Snow White returns to life when one of the prince’s servants, carrying the glass coffin in which the dwarfs have displayed her corpse, stumbles and dislodges the piece of apple from her throat. The Disney 1937 version replaces this fortuity with something more romantically digestible: the prince’s kiss of “true love” that brings her back from death. (And for those still fretting about consent, it’s actually Snow White who bestows the first kiss in the 1937 movie, blown via a dove that she sends to the prince’s lips when he rides up to the castle after he overhears her singing.) Still, the animated version, with its vividly depicted black magic and the stepmother’s disguise as the most hideous of hags, with a grape-size wart perched on the bridge of her nose, terrified many small children back then—as did the wicked witch Margaret Hamilton played in The Wizard of Oz two years later.

However, Walt Disney balanced the story’s horror and dread with the perfectionist flair for visual whimsy and humour that had already become his trademark. This was what transformed it into the highest-grossing animated film of all time in constant dollars. He had spent the preceding decade practising, so to speak, with his “Silly Symphonies,” animated shorts set to musical pieces that often retell Aesop’s fables and other stories. I had never seen the 1937 film in its entirety until I rented it to compare it to the new version. I spent hours running it over and over just to marvel at the details: the obsessive care that Disney’s crew of animators in Burbank had taken to recreate the Teutonic kitsch—beer steins, mechanical clocks, ponderous carved furniture—that fills the dwarfs’ cottage, for example.

And it was Disney who endowed each of the dwarfs with a distinct personality; in the Grimms’ story, they are seven ciphers, their number chosen because seven, like three, is a magical one in the world of fairy tales. The 1937 dwarfs are pure Disney confections. Their body types—hugely enlarged heads, ears, noses, and feet—are not modelled on humans with dwarfism, but on Mickey Mouse. Dopey’s ground-dragging overcoat anticipates the cloak Mickey wears as the sorcerer’s apprentice in 1940’s Fantasia. And although the dwarfs look like Germanic caricatures, they speak like all-American hillbillies. “She’s mighty purty,” says Sneezy when the dwarfs discover Snow White asleep in their bedroom. Their famous yodelling song is more Jimmy Rodgers than Alpine.

But at the centre of the movie is Snow White herself. Her character has been called bland—“a bit of a bore” in the estimation of Roger Ebert’s retrospective assessment of the film in 2001—and this is true, in a sense. The Disney animators were weakest at depicting human faces, and Snow White looks like Betty Boop, with her heavily lashed, nearly circular eyes and cherry mouth. She is “not a character who acts but one whose mere existence inspires others to act,” Ebert writes. But not only does Disney surround Snow White with creatures in constant motion—the dwarfs, the forest critters in nearly every frame—but she is also in constant motion herself, as is her billowing yellow skirt. That iconic garment nearly has a personality of its own. It dips and swings and swirls, filling the frame as Snow White dances—or sings or washes dishes or bakes a gooseberry pie for Grumpy—with meticulously rendered physical grace that must have taken months for her animators to perfect.

Walt Disney envisioned his Snow White as no older than fourteen. The otherwise unknown singer, Andrea Caselotti, whom he hired as her voice, felt obliged to pretend that she was sixteen at her audition, not eighteen as was her real age. Disney had wanted a performer who could sound like a child when speaking but who had the classical training (Caselotti’s parents were music teachers) to render Churchill and Morey’s operatic love songs. Neither Caselotti nor any of the other voice-actors was credited onscreen, and she had to sneak in uninvited to the film’s December 1937 premiere. It was a once-in-a-lifetime job for her (her only credited performance was in a 1945 short). She was paid only US$970 for the role, about US$20,000 in today’s dollars, and Disney was so impressed with the uniqueness of her silvery soprano voice that he effectively barred her from further roles. In her obituary for the Independent in 1997, BBC radio writer Brian Sibley declares: “[H]er singing was exquisite and her rendition of the dialogue was full of naivete, gentleness and compassion.” The supporting characters in the 1937 film were triumphs of technology and visual and audial artistry, but it was Snow White herself who made the movie incandescent.

The makers of the new Snow White tortured their narrative in multiple ways, but their coup de grâce was precisely their destruction of its lead character and the mythic elements surrounding her. Much of the blame for the film’s dismal box-office performance has been laid at the feet of Rachel Zegler herself. It was certainly not prudent to announce her hope that Trump voters “never know peace” (that was half her potential audience) or to deride Disney’s 1937 classic, which Sergei Eisenstein once called the greatest movie ever made. But Zegler is only 24, and she has spent all of her late adolescence and early adulthood in Hollywood, where her head has undoubtedly been crammed with the preposterous progressive cliches of California celebrity-dom for years on end. She deserves some slack.

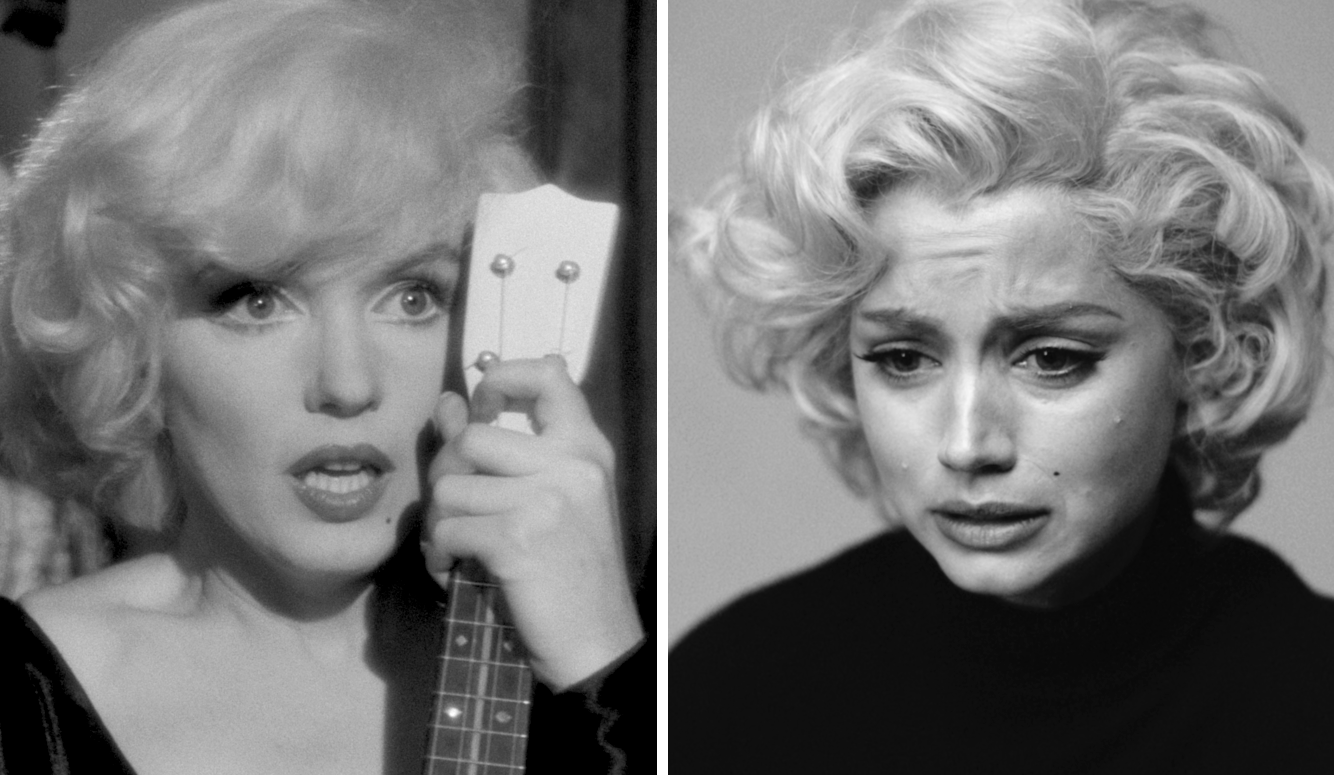

A far greater problem was caused by the limitations of Zegler’s acting talent and personal charisma. Some critics complained that it was ridiculous to cast a Latina with dark-skinned indigenous ancestry as a Northern European princess whose “skin white as snow” is her defining characteristic, at least in the Grimms’ fairy tale and the 1937 cartoon. Yet in 2022’s Blonde, the Cuban-born brunette Ana de Armas was able to achieve an eerily accurate portrayal of the creamy-skinned Marilyn Monroe, whom de Armas facially resembles in no way. Other critics have pointed out that Gadot, a former Miss Israel and Miss Universe, is better-looking than Zegler, even though she was 38 when the film was shot—leading many audience members to wonder whether the new Snow White was really “the fairest of them all,” as the mirror on the wall claimed.

Zegler is perfectly attractive although not gorgeous—and a skilled actress could have used the sheer radiance of her youth to pull off an illusion of beauty that would have mesmerised the audience. But this is exactly what the makers of the new Snow White refused to let her do. They ruthlessly de-feminised this most feminine of Disney’s creations. Rachel Zegler has thick and luxurious hair, but they stuffed her head into a stiff chin-length wig with an unflattering centre parting that looks nothing like the 1937 Snow White’s mass of black curls. The 1937 Snow White’s dress featured girlish puffed sleeves showing off bare arms that contributed to her body’s fluidity of motion. The new Snow White’s arms are sheathed in long electric-blue sleeves that look like metallic tubes and make her dress look like a suit of armour. She is impenetrable. She needs nobody.

And without its central figure—the young and vulnerable maiden who longs for (and finds) a husband and home, and who triumphs over death with love—there is no story of Snow White, nor any other story for that matter. There is only the dreary ideological fable with its wearying message of liberation and empowerment placed front and centre for the edification of aspiring little girlbosses everywhere. This seems to be about the best that Disney, and the rest of Hollywood, can do these days.