Art and Culture

The Best Kind of Political Art

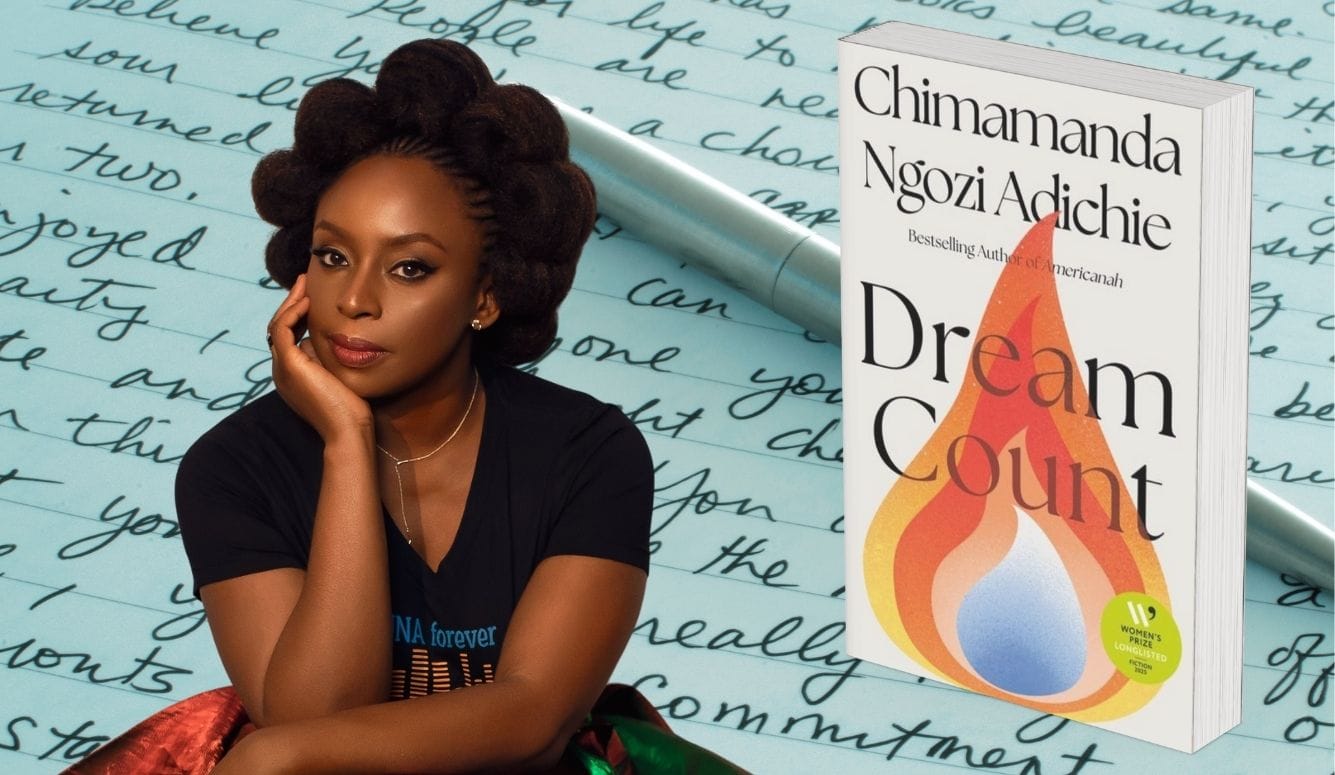

Chimamanda Adichie’s new novel is refreshingly defiant of liberal orthodoxies.

A review of Dream Count: A Novel by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, 416 pages, Knopf (March 2025).

When Dream Count was published in March, it had been twelve years since Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie had published a novel. Her last was Americanah in 2013, and before that Half of a Yellow Sun (2006), and Purple Hibiscus (2003). I know because, having read the previous three and loved them, I had been waiting. I would have read Dream Count no matter what, but something had happened since the publication of Americanah that made me especially interested in Adichie and her work: like J.K. Rowling, she had become a high-profile target of trans activism.

In a 2017 interview on Britain’s Channel 4 news about her non-fiction feminist manifesto Dear Ijeawele, A Feminist Manifesto in Fifteen Suggestions (marketed as “the inspiring guide to raising a feminist”), Adichie had said, “in my opinion, trans women are trans women,” noting that boy and girl children are socialised differently, creating differential privilege and disadvantage.

Then began the ping pong match familiar to anyone who has followed an attempted cancellation: the target apologises and clarifies; if this is done well enough at least some of the mob retreat and things settle down; the target’s view re-emerges in some later interview; the mob returns with renewed vigour; and back and forwards it goes.

For some targets, the initial reaction is enough to scare them off any further public expression of the views that caused it; but not for Adichie. In a 2020 interview with The Guardian, Adichie described JK Rowling’s essay detailing her views on sex and gender as “a perfectly reasonable piece.” In a 2022 interview, again with The Guardian, she took issue with the trans activist movement’s complete divorce of gender identity from gender expression, saying, “You can look however you want now and say you’re a woman.” (The journalist added a disclaimer: “I suspect she’s taking an argument—that trans people don’t want to be policed for how they dress and what stage of transition they’re at—and reducing it to the absurd.”)

Adichie’s two non-fiction works about feminism, the abovementioned 2017 feminist manifesto and the earlier We Should All Be Feminists (2014) (based on her 2013 TEDx talk, which has received more than 8.6 million views to date), are clear that the main problem feminism is designed to address is the fact that people are treated differently on the basis of sex. “‘Because you are a girl’ is never a reason for anything. Ever” she insisted, as part of the third suggestion of the manifesto.

Commenting on her experience in an interview for The New Yorker Festival, Adichie said:

I did say… that I think trans women are trans women, and that I think there is a difference between trans women and women who are born female. And apparently in liberal orthodoxy you’re not supposed to say that, because in the quest for inclusiveness the… left is willing to discard a certain kind of complex truth. And I think there’s a quickness to assign ill intent.

That interview was about the left eating its own. It’s a perplexing phenomenon. It’s one thing for the #MeToo movement to cancel Harvey Weinstein, a then-accused and now-convicted rapist. It’s quite another for activists to go after Adichie: a black woman, an advocate for gay rights in Africa, a feminist, a celebrated member of the literary community. (The same questions arise about them going after Rowling). Whether it’s a tactic deployed consciously, or merely an unintended impact of other chosen tactics, the effect of left-wing auto-cannibalism is to frighten others into conformity. If even she is not safe, then you are certainly not safe; you’d better make sure you know what the liberal orthodoxy is and colour within its lines. Knowing all that about Adichie’s experiences, and her outspoken criticism of the practices to which she and others on the left have been subject, it’s hard not to read Dream Count as a resplendent fuck you to her critics.

The author of Dream Count knows what a woman is and is deliberate in telling women’s stories. Dream Count is about mother-daughter relationships, female friendships, women’s relationships to each other across class lines, pregnancy and motherhood, sexual assault and the emotional trauma that follows it, and the freedom and independence that wealth can offer women.

Adichie also does something artistically intriguing in the novel: although it features multiple characters and events, they are all constructed around a single character’s story, which is based on real life. Her goal, as she explains in the Author’s Note at the end of the book, is to return dignity to a woman from whom public scrutiny and vicious public slander have taken it.

Amid the many women’s stories in the novel, Dream Count features one character in particular who seems to represent the rage of all women critical of liberal feminist orthodoxy condensed to the point of explosion, to adapt a famous phrase from second-wave lesbian feminism.

This character grows up in Nigeria but moves to the United States for graduate study, intending to write a thesis on pornography as sex education for young people, and encounters American liberals for the first time. She writes of her fellow graduate students:

A woman called Eve said, “That’s right-wing!” Everything she disagreed with she called right-wing, and to call it right-wing was to punctuate it with a full stop. Case closed.

A young man with olive skin often said “as a multiracial person” before making his point. I did not know what races he meant, and I was curious to know, but to ask would of course be wrong.

One of the people she encounters describes her as moving ‘money for murderous dictators’:

I had said some of my clients were politicians, but she had turned it to “dictator,” and “dictator” apparently wasn’t enough, it needed “murderous.” A toddler increasing the pitch of her unnecessary tears.

She summarises:

It wasn’t even that they felt offended; it was that offended was the only thing they felt. Perfect righteous American liberals. As long as you board their ideology train, your evilness will be overlooked. Champion an approved cause and you win the right to be cruel.

Of her advisor, she writes:

My adviser confused me. She looked like the distinguished name that she was, with her long silver hair and her serious face. “There’s increasing scholarship on the horrors of the pornography industry, and how inescapably predatory and exploitative it is, but it behooves us, I think, to pay attention to the sensitivities involved, knowing of course that sex work is work.”

Knowing of course. How did she know I knew, and why should I know, and what if I didn’t know? Even saying it like that—“knowing of course”—gave no room for dissent.

“I’m interested in pornography as an educational tool,” I said.

She smiled thinly, as if to say, “Now be serious, please.” I was saying I meant the question of where we learn about sex and she was talking again, saying many words, and I kept hearing her say “liberation.” Everything she said was soft and sank in when touched.

“Liberation? What do you mean? What would it look like?” I asked. She thought I was being provocative but I really wasn’t. Sometimes I thought not having gone to university in America might be why things seemed so hidden under layers of veils; no sooner had I peeled one off than others drifted down.

“Of course you know what I mean by liberation,” she said.

Later she said she didn’t feel she could support my thesis, with the direction I wanted to take, and recommended someone else I could try working with, but by then I didn’t want to work with anyone else. I wanted only to go home.

And on America more generally, this particular character comments:

America is so provincial, like an enormous giant of a man from a bush village who blunders about with supreme certainty, not knowing he is bush because he is blinded by his strength.

There’s something especially satisfying about this character’s expressions of bewilderment and contempt—perhaps because in real life the kinds of liberals she describes so often position themselves as superior to their critics, designating themselves as the ones fit to dispense contempt. Through this character’s reflections on life on an American college campus, we get to experience the inner life of an outsider who has not been enculturated into the relevant leftist norms, and who rejects some of the salient leftist presuppositions.

Where sensationalised media reports of cancellations might direct us to empathise with the alleged victims of a target’s “transphobia,” “racism,” “sexism,” or whatever the allegation is, literature can put us directly into the shoes of the accused. The world looks very different from that perspective. (Another novel that does an excellent job of this is How I Won A Nobel Prize by Julius Taranto, in which a graduate student follows her cancelled adviser to a new university set up to offer refuge to people like him).

Dream Count is art, with or without the political subtext. But I think it’s also the best kind of political art—not the lazy, conformist kind that simply pledges itself to the side of the leftist cause du jour (or perhaps more often these days, the leftist omni-cause)—but the riskier, and more reflective kind, that challenges its own side and demands a higher standard. It is likely to be a cathartic read for anyone frustrated with leftist pieties, and a disorienting read for anyone who counts themselves among the pious. Let’s see if it will result in a fresh bout of cancellation ping pong for its author.