Higher Education

Is the University Of Austin Betraying Its Founding Principles?

Created as a haven for free thinkers, UATX was the last place where I’d expected to encounter ideological litmus tests.

On 8 November 2021, the founders of the University of Austin (UATX) announced the launch of their new project—a school where students would receive “an education rooted in the pursuit of truth.” Unlike Ivy League universities, where “illiberalism has become a pervasive feature of campus life,” the school’s founding president declared, this would be a place “where intellectual dissent is protected and fashionable opinions are scrutinized.” On a web page titled, Our Principles, UATX pledges that it will “renew the mission of the university, and serve as a model for institutions of higher education by safeguarding academic freedom and promoting intellectual pluralism.”

The creation of UATX was heralded as a bold initiative in some circles, but also attracted a number of skeptics. Some wondered if this ostensible homage to the values of classical liberalism wasn’t just a glorified right-wing think tank. Under the headline, Does America Actually Need a New Conservative University?, for instance, Wesleyan University president Michael S. Roth warned Politico readers that UATX was missing the mark by targeting other universities. “I realize that the University of Austin is trying to raise money from donors whose wallets will open more quickly when they hear complaints about woke warriors or pronoun police,” he wrote. “But you shouldn’t misleadingly disparage higher education in general in order to make a place for yourself—especially when declaring one’s devotion to truth.”

At the time, however, I found such criticisms unpersuasive. I’d graduated from a Harvard doctoral program in education leadership three years earlier, and so was well aware of the problems that the UATX founders had described. In our program, the social-justice marching orders were explicit: We were to fight for equity in education, with systemic bias presumed to be the primary cause of unequal outcomes among students. A mass-emailed memo we all received from the Harvard Graduate School of Education (HGSE) Student Council shortly after Donald Trump became President in 2017 urged us to “pledge our support and solidarity with all individuals who face discrimination and systemic injustice,” and “to reflect on concrete steps each of us can take as individuals and collectively to affirm our deeply-held values of equity and inclusion.”

I was hardly a fan of Trump, but bristled at the pressure to conform to such a sweeping directive. And I will quote at length from the frustrated reply I sent in response to that email, as it captures the mindset that would, in time, bring me into the UATX orbit:

It is no secret that the HGSE community bears a strong political and social bias. In some ways, that is appropriate. Most, if not all of us are here because we are dedicated to social justice and because we want to be a part of changing our society for the better. We have spent years dedicated to teaching, learning from, and loving kids… And because we are working for them, we are obligated to not lose sight of the injustices they experience and to face the discomfort that accompanies examining our own role in participating in or benefiting from those injustices. And yes, we should also be fighting against those injustices.

Yet this work and these ideals are contradicted when we fall into the trap of shutting down in the face of conflict or opposing ideas, demanding that total agreement with a single narrative is the price of admission we as HGSE students must pay in order to belong to this community. By demanding that we “raise a loud and strong voice against all actions and messages contrary to our ideals,” this pledge is asking us to act reflexively and unthinkingly towards anyone who espouses a thought or an idea we dislike. It also contradicts the idea of “learning through disagreement” mentioned in the pledge.

As it happens, President Obama dedicated his farewell address to this very problem, saying, ‘For too many of us, it’s become safer to retreat into our own bubbles, whether in our neighborhoods or college campuses or places of worship or our social media feeds, surrounded by people who look like us and share the same political outlook’… Yet, as he states earlier in the speech, ‘Democracy does not require uniformity’… We NEED contradiction, disagreement and opposition to do our work better. New ideas are not born from repetition and habit. They are born out of surprise, new insights and often discomfort or even anger.

The atmosphere I observed at Harvard was starkly different from what I’d experienced elsewhere. In 2005, while in my mid-twenties, I left jobs teaching middle and high-school students to earn an MBA at the Rotman School of Management in Toronto (something my family and friends joked about given my propensity to wear flowy skirts and play folk songs at open-mic events). Business school proved an eye-opening experience. It forced me to confront ideas about economics, capitalism, and social welfare that I’d always taken for granted. Is corporate greed a force for evil if it leads to innovations that save lives? Is protectionism good if it leads to higher prices for consumers and bankrupts farmers in other countries?

I developed an appreciation for the sinking feeling I got when I suddenly realised I’d been limited in my thinking—an appreciation bolstered by the vigorous approach my classmates and professors brought to debates. This, in turn, led me to found a new initiative at the business school following graduation, called I-Think (a play on then-dean Roger Martin’s term, Integrative Thinking), which helped teach secondary school teachers and administrators how to explore opposing ideas.

A decade later, I felt duty-bound to put these ideas into practice at Harvard by pushing back against what seemed like a newly ascendant form of ideological tribalism. A teacher’s mandate should be to provide students with a tapestry of ideas, and the tools to evaluate them; not tell them to conform. I believed that education should enable each student, in the words of James Baldwin, “to decide for himself whether there is a God in heaven or not. To ask questions of the universe, and then learn to live with those questions.” This is the path, he explained, to forming one’s very identity.

So when I saw the original UATX press release, I went all in. It helped that I’d already started a similarly oriented project with my friend Ilana Redstone, a sociologist at the University of Illinois whose work on examining the dangers of settled thinking had already started to attract public attention. (I particularly recommend her popular video series, Beyond Bigots and Snowflakes, which explores the underlying mechanisms that lead to polarised and oversimplified forms of thinking.) We’d founded what we called the Mill Center—the name being a homage to English philosopher John Stuart Mill—which, like I-Think, was focused on working with educators to support free-thinking classroom environments.

Things moved quickly, as the leaders of UATX knew of Ilana’s work, and had recruited her to serve as one of the university’s founding faculty fellows. When she shared details about the Mill Center, UATX saw an obvious fit, and so invited us to join as an affiliated institute in Fall 2022.

We agreed, and in so doing surrendered our independent organisational status. We’d be responsible for raising our own funds, but the school provided a two-year start-up loan to help us get off the ground. Shortly thereafter, a private donor came away from a meeting with Ilana so impressed that he dedicated his substantial UATX donation to our new project.

At first, the UATX start-up team was working in a nondescript office park. By 2023, however, it was operating out of Austin’s Scarborough Building, steps from the Texas Capitol, as a fully-fledged private liberal-arts university. Ilana and I ran the newly launched Mill Institute remotely, with a double mandate to support K-12 educators across the country, and to advise the university leadership in regard to fulfilling its larger mission.

We got to work and grew quickly. Our institute helped teachers promote open dialogue and viewpoint diversity in regard to contentious topics, by supporting them with resources, professional development, and a national teacher fellowship. The key, we believed, was to help students challenge their own entrenched views, thereby advancing Mill’s famous insight from On Liberty, that “living truths” become obscured when we limit our thinking to “dead dogmas.”

Our Viewpoint Diversity Challenge, run in more than 200 classrooms across the country, taught about the dangers of echo chambers, and offered ground rules for classrooms that wanted to avoid “settled thinking.” After the Hamas attacks of 7 October 2023, we released a new challenge that asked students to define and understand a set of contentious words (such as apartheid, genocide, and Zionism); and explore how opposing definitions of such words might bring more nuance to their understanding of the conflict. Before the 2024 election, we also released a set of resources to help teachers introduce topics such as immigration, abortion, free speech, and economic inequality without resorting to oversimplified political binaries. More than ninety percent of surveyed teachers told us they believed that these resources helped equip (and motivate) their students to discuss these issues with one another.

In the space of less than two years, we grew our network to include more than 1,700 teachers across 43 states and 11 countries. The educators we worked with came from across the political spectrum and taught at a diverse range of institutions—from elite private schools to large urban public and charter schools, in red states and blue states alike. They revelled in the opportunity to talk openly, often lamenting that it was hard to do so in their own school environments. Teachers in Florida and Texas found that they had similar challenges to those in Massachusetts and California, even though the pressures on them typically came from different directions. Some acknowledged the impact of counterproductive diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) policies that had proven to be censorious and divisive. Others wanted a way to engage parent groups with conflicting political affiliations.

The response from UATX was decidedly positive. Pano Kanelos, then the school’s president, warmly promoted our work and spoke at our events. When a team from 60 Minutes did a segment on the university, I was selected to be interviewed and filmed teaching. University leaders forgave our start-up loan—a signal that our project was providing substantial value. And the central fundraising team cited the Mill Institute regularly as a case study when extolling the school’s activities. As recently as January 2025, UATX was developing a fundraising campaign focused solely on the Mill Institute.

Even while we were gathering momentum, however, there were concerning indicators. Early in our tenure, the administration grew noncommittal about our advisory role. It seemed to us that while the university appreciated the way we were holding a mirror up to educators at other schools, there was little appetite for examining the culture at UATX itself.

In time, Ilana became so concerned about the university’s politicised postures (more on that below) that she stepped down from her Mill Institute leadership role. She’d embraced the UATX project primarily as a means to help Americans manage their ideological differences without resorting to censorship and trolling—not to enlist as a culture-war combatant.

For my own part, I tried to remain open-minded. Starting a university, I reasoned, is a complex undertaking, and so it was expected that all would not go exactly to plan. Yes, it disturbed me that some colleagues used “party horn” emojis on Slack when responding to circulated articles describing political hardships at other universities—as if we were in a zero-sum battle with the rest of academia. But I did my best to ignore such episodes.

It turned out that what I was observing was symptomatic of the larger ideological tension developing within UATX between two camps—those specifically championing an unabashedly “anti-woke” conservative agenda, and those (such as myself) prioritising academic freedom more generally.

At first, I was relieved to observe, the university administration, faculty, and advisors spoke openly about that tension. Moreover, the academic-freedom side seemed to have the upper hand. From my perch in Toronto, I was still able to participate in spirited good-faith discussions about, among other topics, the role universities play in society and the dangers of censorship. I didn’t feel the need to keep my mouth shut in discussions—even though my perspectives often deviated from many colleagues.

And so I felt blindsided when, on 3 March, UATX ended its relationship with the Mill Institute.

That morning, I got onto what I thought was a casual call with a senior colleague, someone who spoke with me regularly in order to keep the university updated on Mill Institute activities. Once we were past the opening pleasantries, it immediately became clear that something was wrong.

My colleague told me that we needed to talk about a social-media post of mine that “had become a big problem.” I rarely post anything online, so I was confused about what he meant. Apparently, it had something to do with DEI, and had angered a major funder. “We’re trying to slow things down,” my colleague told me. I got the impression that he was upset about the message he was delivering.

I dimly recalled that I’d written something about DEI on LinkedIn. But I was still confused, because it had seemed like such an innocuous post (to me, anyway); and I couldn’t imagine how it would upset anyone in the UATX community, let alone lead to this ominous phone call.

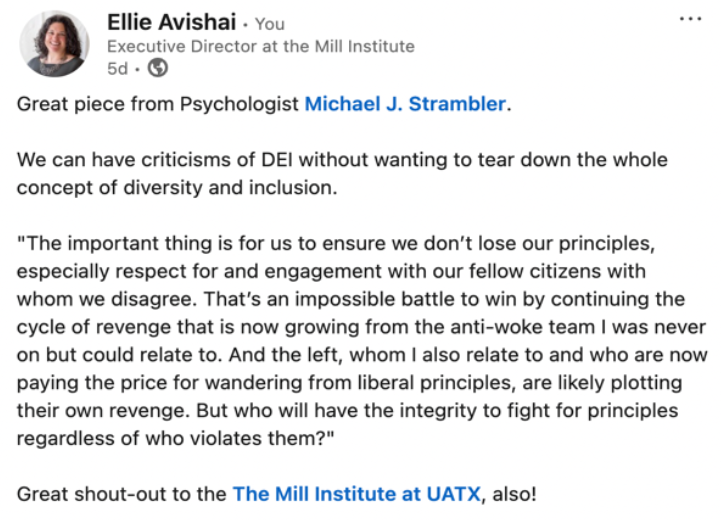

In that post (reproduced below), I’d thanked writer and Yale professor Michael J. Strambler for mentioning the Mill Institute in a magazine article titled The False Binary of the DEI Debate. The piece, which struck a liberal tone, walked readers through the pros and cons of DEI programs, concluding that regardless of one’s position on DEI, none of us should lose respect for those who hold different opinions.

My sin, it seems, was that I’d written, “We can have criticisms of DEI without wanting to tear down the whole concept of diversity and inclusion”; and that I’d appreciatively quoted Strambler in a manner that implicitly criticised Trump’s aggressive approach to dismantling DEI programs. In promoting a more open-spirited view, I was refusing to condemn DEI without reservations or qualifications.

I knew, of course, that members of the UATX leadership team were highly critical of the impact of DEI on higher education—a critique that I largely shared. The university’s founding constitution, for example, explicitly instructs administrators that “admission and graduation decisions shall be made strictly without regard to race, gender, sexual orientation, political affiliation, or religious faith.” A headline on the UATX website that reads, “Statement of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion” is followed by the text of the Declaration of Independence, highlighted so as to emphasise the sentence proclaiming that “all men are created equal.” In January, the university published a video featuring co-founder Joe Lonsdale and Niall Ferguson, one of UATX’s most highly visible faculty members (and the architect of its constitution), under the slogan, “DEI, ESG, and BS are out.” (“ESG” stands for Environmental, Social, and Governance—a framework for aligning corporate behaviour with progressive values.)

DEI, ESG, and BS are out.

— University of Austin (UATX) (@uaustinorg) January 24, 2025

UATX is bringing the global vibe shift to higher education with @nfergus and @JTLonsdale. pic.twitter.com/6CVz8OvTHm

In a speech delivered last year, Ferguson argued that

The path to hell for universities has a sign that reads, “Diversity, Equity and Inclusion.” I know these words sound nice and nobody wants to be against them but I have to tell you that in George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four, words mean the opposite of what they appear to mean. What the words diversity, equity and inclusion turn out to mean is… uniformity of thought, no equity—no due process—for anyone who fell afoul of the inquisition, and exclusion of conservatives and, indeed, anybody who was deemed to be too far to the right.

Notwithstanding Ferguson’s obvious hyperbole, I appreciated his point. What I did not appreciate was the university’s increasing tendency to fuse this kind of substantive critique of DEI with caustic criticism of other universities—including UATX’s nearby neighbour in Austin, the University of Texas. On 20 February, for instance, the official X account of UATX posted,

High School Seniors, If these college courses sound interesting to you…Latinx Sexualities, Queer Television, Chicana Feminisms, Black Queer Art Worlds, Queering Black Religions… there’s a really good option for you across town.

Around the same time, the UATX LinkedIn account posted, “Dear American universities, Thank you for self-immolating and giving us the best students. Best, UATX.” On 24 February, the aforementioned co-founder, Joe Lonsdale—who is also a significant UATX funder, and the chairman of the Board of Trustees—posted on his personal account,

About 10% of the people around the university we founded think it’s lowbrow or anti-intellectual to mock communists. Fortunately, I’m the chairman, not them! Communists deserve to be scorned relentlessly, be they USAID grifters, LatinX theory academics, or DEI administrators.

The tone of these communications baffled me. They betrayed a lack of patience for the more nuanced conversations about the historical challenges that DEI initiatives were originally designed to address. Still, it never crossed my mind that, at UATX of all places, I’d feel pressured to conform to any kind of institutional dogma; or that a more moderate perspective about DEI could be considered what Orwell called thoughtcrime. On the contrary, I assumed that opinions such as mine proved the university’s rule: I could freely express a critique—not just of the university, but of the federal government—believing that my (admittedly rather unoriginal) perspective added to the intellectual diversity of the university.

But what happened next suggests I was wrong.

By 5pm on 3 March—the same day I first heard that my LinkedIn post was a “problem”—my team of five and I were all on our way to being pushed out of UATX. I got the news from a junior dean whom I barely knew. He told me bluntly, “the trustees and the management have decided that we’d like to wind up Mill, and I’m calling to let you know that we’re letting you go.”

Editor’s note: When a Quillette editor contacted UATX for comment in regard to the events and issues discussed in this article, we received the following response: UATX is unapologetically opposed to DEI. We believe these programs institutionalize ideological orthodoxy, lower academic standards, and promote a view of human identity that undermines individual dignity. That position is central to our mission. That mission: to offer the best undergraduate experience in the world to students dedicated to the pursuit of truth. We’ve been cutting partnerships and contractor work that don’t directly improve the academic experience for our students or help us recruit the right ones.

The university’s constitution, which details the scholarly freedoms owed to faculty and students in detail, contains no protection for affiliated institutes. I had no recourse, and there was no discussion. Two days later, when an internal email was circulated to update my (former) colleagues on the issue, it was couched in vague euphemisms:

As part of the Board’s conversations about our strategy for the next phase of the University, the decision was made to restructure the Mill Institute. This restructuring is part of our ongoing efforts to be laser-focused on the university’s core mission and goals as well as its broader academic and institutional priorities.

For all Ferguson’s warnings about Orwellian distortions of language, the message struck me as a lot like doublespeak.

In the days that followed, several former colleagues reached out to me and told me that many of the faculty and students had recently complained about the tone of the university’s communications, especially the social-media insults hurled at other schools. Perhaps my own post had simply come at an inopportune time—while the internal politics of the university were inflamed by this larger controversy. At any rate, it seems I’d stepped on an ideological landmine in a place where no mines were supposed to exist.

If UATX officials want to prevent their school from operating merely as a high-concept redoubt for conservative culture warriors, they should re-commit to the school’s own founding principles, and leave the vitriolic “anti-wokeness” fusillades to podcasters and YouTubers. The school must be unwavering in its commitment to free inquiry, and show itself to be a welcoming home to a diversity of views, not just those that fall within a range acceptable to its biggest funders and most influential administrators. Stoking grievances against other universities might be a good way to bring in donor dollars. But in the long term, it’s a losing strategy, as institutional hypocrisy inevitably has a dispiriting effect.

As Ruth Bader Ginsberg once put it, “the true symbol of the United States is not the bald eagle. It is the pendulum. And when the pendulum swings too far in one direction it will go back.” What this means to me in the current political moment is that there are no permanent victors in the culture war. And as we’ve seen over the last year or two, yesterday’s scrappy dissident can easily reinvent himself as tomorrow’s ideological autocrat once he feels that his side is gaining the upper hand.

This is already happening at institutions controlled by Trump and his acolytes. And I fear that UATX may be moving in the same direction. When it comes to smashing intellectual freedom and diversity, I can attest, Bader Ginsburg’s pendulum can act as a wrecking ball.