Politics

The WEF’s Gender Disinformation Campaign

A combination of activism and evolved cognitive bias results in suboptimal social and economic policies.

In the coming weeks or months, the World Economic Forum will release the Global Gender Gap Index (GGGI), its annual report on the state of gender equality throughout the world. The index ranks countries as more or less gender equal using a composite of health, educational, occupational, and political indices, and produces a purported measure of the extent to which nations provide equal opportunities for women and men. However, the index is selectively designed and it is a political document more than a balanced assessment of gender equality. Its design ensures that women will always lag behind, and it is often used to pressure governments to adopt policies favouring girls and women at the expense of boys and men.

As Gijsbert Stoet and I wrote in these pages a few years ago, many activists in the media and elsewhere are happy to run with this narrative and lament the poor treatment of girls and women even in some of the wealthiest, healthiest, and most equalitarian nations in the history of our species. These are nations in which women have longer lifespans, are better educated, and are often more satisfied with their lives than men are. These are the same nations in which boys and men fall behind in many domains of life, but the GGGI labels women as broadly disadvantaged even so.

The biases in the construction and use of the GGGI belie the real goal, which is to generate a narrative that supports the continued flow of resources to girls and women without concern for broader social costs or the costs to boys and men.

Bias in the GGGI

The GGGI provides a broad, cross-national comparison of women and men but it is largely restricted to domains that often show inequality in outcomes favouring men. There are no calls, for instance, to address sex differences in work-related injuries and deaths or sex differences in suicide rates or in homelessness. Simply put, like its predecessors, the 2024 GGGI report is designed to cherry-pick carefully selected factors to support advocacy for enhanced resource flow to girls and women. It is not an unbiased assessment of gender equality.

No doubt, the upcoming report will be more of the same. I won’t belabour all the issues with the GGGI, as I covered them in my last Quillette article on this topic. I will, however, highlight a few of them to make the point that its primary purpose is to distort policy to benefit girls and women by reallocating public and private resources, rather than to acknowledge the needs of all people. As stated in the preface of the 2024 GGGI Report:

Big lifts in economic gender parity are needed to ensure that women have unfettered access to resources, opportunities and decision-making positions. Governments are called on to expand and strengthen the framework conditions needed for business and civil society to work together in making gender parity an economic imperative. [italics added]

The first flaw, as already noted, is the selection of factors that highlight possible disadvantages to women while ignoring widely recognised disadvantages faced by men. But this is only the beginning of the distortion created by the GGGI.

It is also important to understand that the GGGI is designed so that men can never be shown to be disadvantaged on any factor, much less disadvantaged overall. For example, if women are behind men on, say, education in a given country, this is scored as an inequality with women as victims. If, on the other hand, women are ahead of men in education (as is true in many countries), this is scored as equality. In other words, the measure is capped at parity even in situations where boys and men are doing more poorly than girls and women.

This approach ensures that boys’ and men’s disadvantages are hidden, and that “parity” will not be achieved until women are in an equal or superior position on every single factor in the entire GGGI index. No one would know this unless they slogged all the way through to Appendix A on page 64 of the 2024 report, which acknowledges this methodological sleight of hand:

Hence, the index rewards countries that reach the point where outcomes for women equal those for men, but it neither rewards nor penalizes cases in which women are outperforming men in particular indicators in some countries. Thus, a country that has higher enrolment for girls rather than boys in secondary school will score equal to a country where boys’ and girls’ enrolment is the same.

Men’s well-documented educational disadvantages in many economically developed nations don’t count as an inequality worth addressing or even mentioning despite the gap’s broad social implications. This gap has likely contributed to the secular decline in young men’s labour-force participation and marriage rates in places like the United States. Women—and to a lesser extent other men—have little sympathy for struggling, lower-status men like these, but this contempt is counterproductive and harmful to women in the long term.

Men (and women) have some responsibility for preparing themselves for life in the modern world, but policies that facilitate the preparation of these men for full engagement in the modern economy are also important. Their underemployment reduces the overall tax base that provides disproportionate benefits to women, and leads to distortions in the marriage market especially for women who historically married men employed in well-paying blue-collar professions.

In the subindex for healthy life expectancy, “the equality benchmark is set at 1.06 to capture that fact that women tend to naturally live longer than men.” By this metric, women are considered disadvantaged—and therefore in need of greater healthcare investments—in nations where they live only four years longer than men. It is true that biological factors contribute to lifespan differences, as shorter male lifespans are common in species in which males compete intensely for status. However, if we accept a biological basis for the sex difference in healthy life expectancy as a rationale for setting this benchmark at 1.06, then we must also accept that the same intense male-male competition and women’s preference for high-status marriage partners will influence sex differences on other indicators that contribute to the overall GGGI.

In short, male-male competition and women’s preferences result in men being more intensely focused than women on achieving status in a niche that is valued in the wider culture. Through this, they obtain some level of social potency and access to resources that are important in that culture. This focus on cultural success contributes to men’s willingness to pay the costs (e.g., longer work hours)—the associated stressors contribute to the sex difference in healthy life expectancy—needed to achieve economic and social and political success. Both domains are included in the generation of GGGI scores and men’s advantages in them are considered issues that need to be addressed, as noted in the preface of the 2024 report:

Since 2012, the Gender Parity Accelerators have worked towards gender parity in economic participation—scaling policies and strategies to improve women’s representation in the workforce and in leadership—as well as pay equity.

The GGGI is a useful index of how well nations provide educational, economic, and political opportunities to girls and women, but it is not an objective indicator of broad gender equality. Rather, the index is designed to create an illusion that women are continually and broadly behind men in areas that are largely a concern of work-focused gender activists. Unfortunately, the annual media outrage about these inequalities creates a broader dynamic that distorts policy decisions in ways that consistently favour girls and women, with an indifference to or even contempt for struggling boys and men.

How Did We Get Here?

In many hunter-gatherer and other small-scale societies, pregnant women and women with young children require—and usually receive—support from the wider group, including their husbands, friends, and kin. This communal support is critical to keeping children alive and healthy in contexts where as many of half of them die before reaching adulthood. The cooperative investment in women’s well-being is beneficial to those involved and is achieved in part by resource transfers. Although there is variation across these groups, women in most of them consume more calories across their lifespan than they produce (e.g., through foraging), whereas men produce more calories (e.g., through hunting) than they consume. The difference between women’s production and consumption is addressed through transfers from men to women (grandparents often contribute too), which is largely from husbands to wives but also comes from other men who share the proceeds of their hunt. A remarkably similar pattern occurs in economically developed nations, where women contribute less in tax on average than they consume in public benefits and men contribute more than they consume.

Whatever the context, women with more social support and influence and greater access to material resources, whether they come from husbands or kin, have healthier children and often children who are more likely to survive to adulthood than their less fortunate peers. Given these relations, we would expect women to be especially sensitive to the quantity and quality of social support and material resources flowing to them and even implicitly expect it from the broader community. We see a reflection of this expectation in a recent analysis published by the British Medical Journal:

Ultimately, whole communities and local governments need to be involved in the provision of care. This will free up women to contribute more to the paid work economy, to engage in voluntary and leisure activities, to have more time for themselves, and to safeguard their careers with arguably less compromise to, and negative effect on, their mental health and general wellbeing.

Women’s concern about resource flow is well-founded, and many of them facilitate this with the development of friendships and through marriage. With the latter, there is a tendency for women to monitor men’s status and resources and to have a strong preference for men with substantial resources and the ability to provide support. For some women, this manifests as a comparison between their current life circumstances and how these circumstances would be improved if they married a prospective husband.

The expectation of an improvement in their life makes perfect sense from an evolutionary perspective, but it also results in many women comparing themselves to men in domains that are important to them. This results in some women envying men’s economic success and social status. In other words, these are things that capture women’s attention and the envy results from men having more in these domains, on average, than they do. It is not a coincidence that many of these domains, including occupational and political participation, are incorporated into the GGGI.

In modern nations, many women bypass the middleman and directly pursue status and access to resources, although this is not the preference of all or even most women. A nationally representative UK survey indicated that about fourteen percent of women preferred a work-focused life, sixteen percent prefer a home-focused life, and the remainder prefer a mix of the two. More than four out of five of the well-educated and work-focused women had full-time careers, whether or not they had children; “patriarchal values have very little impact, and child care responsibilities have no impact at all on work rates among work-centered women.” The success of work-focused women in these societies belies the argument that economic disparities, including those measured in the GGGI, are only or largely due to things like the ill-defined patriarchy.

In traditional contexts (like hunter-gatherer groups), most women have a mixed strategy; they obtain some resources for themselves and get the rest from husbands, kin, and the broader community. In this light, it is not surprising that most women in economically developed nations have a mixed, work-home preference. Most of the women with this preference reduce their work hours and focus more on their family if they have high-earning husbands, just as Magdalina Hurtado and colleagues found for women married to successful hunters in hunter-gatherer societies. In short, when men provide resources to the family, many (not all) women shift their focus to activities that will improve the well-being of their children and themselves and invest less in directly gaining access to these resources.

Accordingly, women’s social strategies function to increase their network of social-emotional support and their access to resources through the development of friendships with other women and through relationships with men. These strategies include inculcating and enforcing social rules that favour women, even at the expense of boys and men. This same-sex bias is quite large—only about one in seven men show the same level of bias as the average woman. The magnitude of the same-sex bias and comfort in imposing costs on males is larger among gender activists—that is, women competing in the same cultural and occupational spheres as men—but it goes well beyond them.

Maja Graso and colleagues studied the cost-benefit tradeoffs associated with implementing different types of policies, and concluded:

This disparity [women favouring women at a cost to men] suggests women may prioritize one another’s welfare over men’s in the construction or approval of social, educational, medical, and occupational interventions. If so, female policymakers might be especially wary of advancing policies or initiatives risking harm to other women, but less so when they risk harming men.

In other words, on average, women favour an ethos or explicit community or organisational rules that enhance their well-being even if doing so imposes a cost on boys and men. Playing the victim card is one way to push for these policies, as Cory Clark has argued. In the popular media, women are often cast as victims of an amorphous patriarchy that must be suppressed by government intervention to improve the lives of women. While government interventions are sometimes needed, the coverage of associated issues is asymmetrical, focusing on women’s but not men’s concerns.

Playing the victim card to exploit this asymmetry is an effective strategy that taps inherent biases, as illustrated by a series of studies by Tania Reynolds and colleagues:

Across six studies with a total of 3,137 participants, we found consistent support for our hypothesis that third parties exhibit a biased application of moral typecasting which cognitively links females with victimhood and males with perpetration. This pattern emerged not only with explicitly social scenarios … but also for animated objects devoid of humanizing attributes. Not only did participants more easily detect female victimization and suffering, they also felt more warmly towards female versus male victims and perceived their suffering as less deserved and less fair.

This cognitive bias—the belief that women are more prone to victimisation and thus in greater need of protection—was found for men and women and makes sense from an evolutionary perspective. In traditional contexts (e.g., hunter-gatherer societies), men benefit from protecting and providing for women and their children. Men and people in the broader community have cognitive and emotional biases that result in enhanced protection and provisioning of women, and women have biases and social strategies that facilitate this dynamic. These biases and social dynamics make sense and are broadly beneficial in the small-scale communities in which they evolved. But when scaled to larger societies, these biases can result in policy distortions that do more harm than good.

These social-emotional dynamics and cognitive biases can be and are used to manipulate policies in ways that increase the flow of resources to girls and women, regardless of their impact on the wider society. The way in which the GGGI was constructed and its use by the media and policymakers reflects these same social and cognitive biases.

Basic Index of Gender Inequality: BIGI

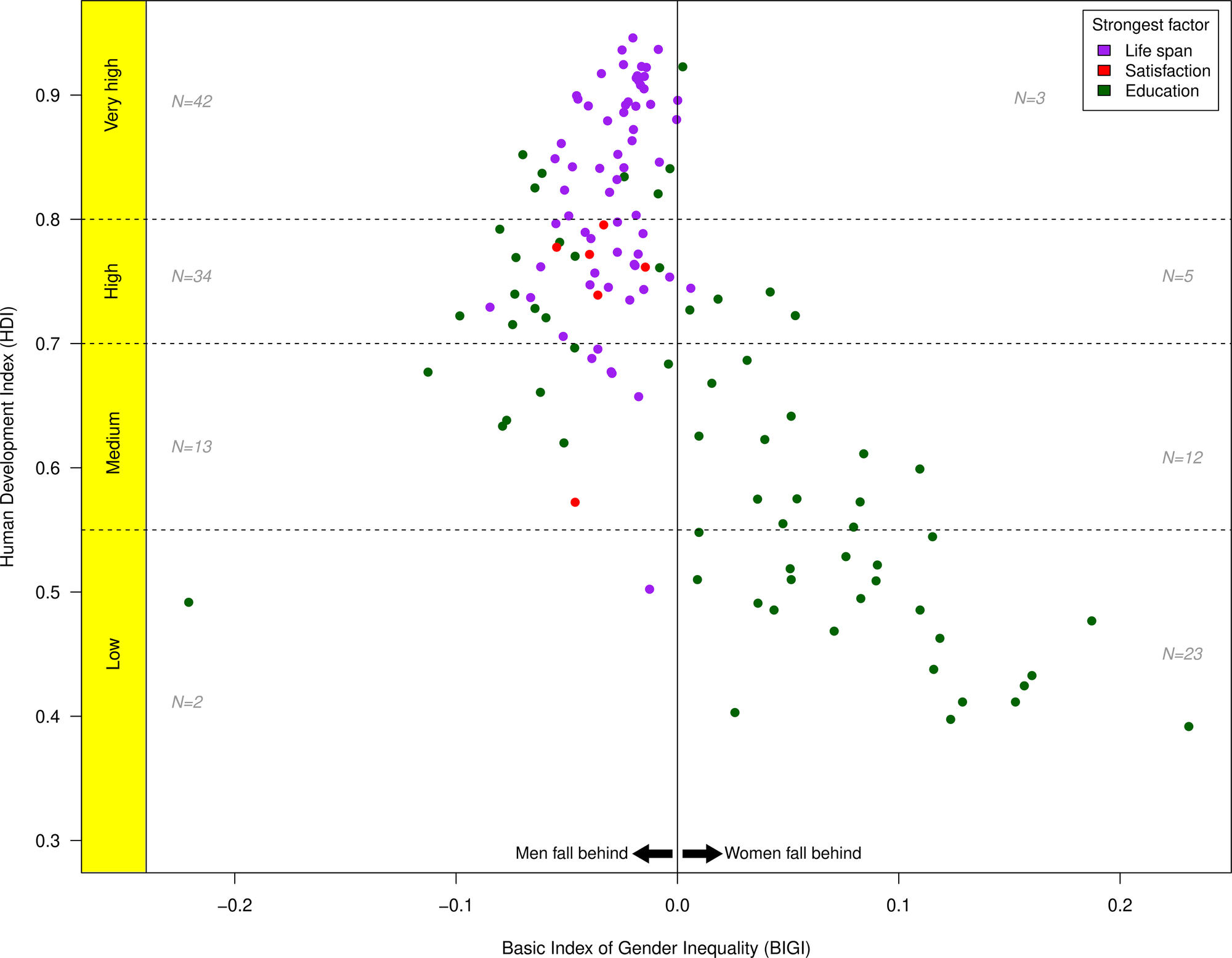

In our earlier article on the GGGI, Gijsbert Stoet and I explain how we developed the Basic Index of Gender Inequality (BIGI) to provide a simplified and less biased assessment of how well nations are meeting the basic needs of girls and women and boys and men. The idea is that nations should provide an opportunity for everyone to have the educational opportunities needed to lead a long, healthy, and satisfying life. We used these metrics because they are transparent and relevant across different types of societies and different levels of economic development, assuming a universal preference for a long and healthy lifespan. Unlike the GGGI, the indexes are not capped at parity but rather can reflect girls and women falling behind, boys and men falling behind, or actual parity.

This approach yields a much more nuanced and realistic picture of how well different nations are meeting the basic needs of their citizens, whether these citizens are female or male. The figure below shows our overall results based on national rankings on the Human Development Index (HDI). The HDI rankings indicate overall quality of life, as indexed by things like overall disease burden and lifespan, and it clusters countries into the categories of very high (e.g., United States, Japan), high (e.g., China, Mexico), Medium (e.g., Cambodia, Guatemala), and low (e.g., Liberia, Somalia).

Each point represents a country, and the colour indicates the index with the largest sex difference. The largest disparities are in Low and Medium countries and they are largely driven by girls’ relatively poor educational opportunities. In contrast, for High and Very High nations, the disparities favour girls and women largely due to men’s shorter lifespan and boys’ lower levels of primary and secondary school completion and lower literacy rates.

When measures of well-being aren’t artificially capped at parity, as they are with the GGGI, we get a more realistic picture. Boys and men are doing better in some areas in some parts of the world, girls and women are doing better in some areas in other parts of the world, and sometimes the sexes are doing about the same.

The foundation of the GGGI is based, at least in part, on the goals and beliefs of gender activists. The ostensible goal of increasing gender equality is actually a cover for a more self-serving push to increase women’s access to political power and to direct more and more social and economic resources to themselves. The biases that contribute to these dynamics, as noted, make sense and are widely beneficial in the small-scale societies in which they evolved, but they lead to policy distortions when uncritically enacted in modern societies.

It might be argued that a lack of equality in certain domains, such as representation in high-level political offices, is due to men’s suppression of women’s ability to seek such offices. This was the case historically but it is no longer the case in many nations today. Women are just as likely as men to win elections in economically developed nations, but they run for office less often in part because they find the highly competitive, winner-takes-all nature of elections to be more aversive than men do. Women are generally more risk averse than men and across cultures men have more to gain (e.g., enhanced marriage prospects) from achieving political influence. That this produces a larger share of men in political office and in other domains that confer high social status is not surprising.

In any case, it is work-focused and activist women who are leading the charge here. When combined with women’s general same-sex bias and men’s and women’s cognitive and social biases to see women as victims in need of protection, we have the potential for policy distortions that are not in the best long-term interest of society. The upcoming GGGI release will no doubt continue to push the activist agenda, but it should be seen for what it really is.